Predictors of Arrest During Forensic Assertive Community Treatment

An enduring issue in community mental health concerns the overrepresentation of persons with mental illness within the criminal justice system ( 1 ). Although precise estimates remain elusive, reports on structured interview surveys suggest that the prevalence of mental illness, broadly defined, in jails and prisons in the United States may range as high as 16% ( 2 ). These estimates are above the 6.3% rate for serious mental illnesses in the general population ( 3 ). As a consequence, significant attention and resources have been geared toward addressing this problem, including various jail diversion programs, mental health courts, and mandatory outpatient treatment programs. These intervention strategies typically rely on various forms of legal leverage and therapeutic adjudication to promote treatment adherence among persons for whom traditional community care is insufficient. Although these strategies are promising, a growing body of evidence suggests that their effectiveness is dependent on the type and intensity of treatment services delivered ( 4 ).

Assertive community treatment (ACT) is an evidence-based strategy designed for persons with serious mental illnesses who have difficulty engaging in treatment and who are at high risk of repeated hospitalization ( 5 ). Despite variations over its 30-year history, the basic elements of ACT include high staff-to-patient ratios, use of mobile treatment teams, forgoing brokered services for provision of direct care, and providing these services in the community rather than in office settings ( 6 ). Studies have consistently shown that this model is effective at reducing hospital care and promoting community tenure among patients who are difficult to engage in care. However, the ACT model has not been found to be effective in reducing arrest and incarceration among at-risk patients ( 7 ).

Nonetheless, the effectiveness of ACT in preventing hospitalization and engaging difficult patients has prompted the development of adaptations for offenders with serious mental illnesses. Forensic assertive community treatment (FACT) is an adaptation of the ACT model for persons with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses who are involved with the criminal justice system. Recent studies have suggested that FACT programs are rapidly emerging across the United States ( 8 ) and that more FACT programs are needed ( 9 ). However, existing programs vary substantially in the treatment services they provide. In the first published study of FACT, Lamberti and colleagues ( 8 ) found that programs differed in their criminal justice partnerships and whether they incorporated residential services or included an addiction counselor in their treatment teams. In light of this variability, researchers have emphasized the need to develop and standardize FACT ( 9 ).

Given this need, further attention to the question of what adaptations of the ACT model are necessary to prevent criminal recidivism among adults with serious mental illnesses appears warranted. In light of the lack of controlled experimental data, development of the FACT model can be guided by contemporary crime prevention principles. According to the principles of risk, needs, and responsivity, prevention efforts should target the modifiable risk factors for criminal recidivism ( 4 ). Although several studies have examined recidivism risk factors among forensic patients receiving general community treatment ( 10 ), there have been no published studies examining risk factors among patients receiving FACT. The purpose of this study was to identify predictors of arrest within an established FACT program, Project Link.

Methods

Records from all service recipients in Project Link during the period of 1997 through 2003 (N=130) were reviewed and matched with the New York statewide criminal justice database. Details regarding Project Link, a prototype FACT program established in 1995, are presented elsewhere ( 11 , 12 ). Briefly, all enrollees are required to have a DSM-IV psychotic disorder, to be at least 18 years of age, and to have past or current involvement with the criminal justice system. Demographic, clinical, and mental health utilization data were extracted from medical records and entered into a SPSS data set. This data set was subsequently matched with the New York Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) database to ascertain numbers of parole actions, probation actions, and arrests for misdemeanor, felony, nonviolent, and violent crimes before and after enrollment with Project Link. Violent crimes were defined according to DCJS protocols, to include homicide, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. The study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subject Review Board.

Analysis proceeded in several steps. First descriptive statistics were calculated for all demographic and clinical variables. Second, we evaluated changes in alcohol and drug use before and after enrollment by creating a dichotomous variable that included reports of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or opiate use. Third, a Poisson regression model was constructed to explore the interaction of criminal justice characteristics with clinical and service utilization factors. Any arrest for a new criminal charge during treatment was used as the dependent variable. The Poisson model was chosen for its sensitivity to low, repetitive counts of dependent data and its ability to make adjustments for length of individual treatment.

Results

The mean±SD age of the sample was 34.3±10.1 years, and 108 (83%) were male. Over half (N=90, 69%) were African American, 29 (22%) were white, eight (6%) were Hispanic, and the rest (N=3, 3%) belonged to another race or ethnicity. Most (N=112, 86%) were single and never married, whereas ten (8%) were divorced and eight (6%) were married. Many (N=77, 59%) had not completed high school or obtained a GED, although 30 (23%) had completed high school and 23 (18%) had attended college. Most (N=100, 77%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia; bipolar disorder (N=16, 12%), psychosis not otherwise specified (N=12, 9%), and schizoaffective disorder (N=2, 2%) were also present in the sample. Most participants (N=87, 67%) used either alcohol or drugs during treatment.

Mean length of treatment was 126.1±99.0 weeks. At the time of data collection 105 (81%) of the patients had been discharged to a lower level of care, 25 (19%) were incarcerated, 12 (9%) refused treatment, five (4%) were deceased, five (4%) had moved, and four (3%) were receiving long-term hospitalization. Contact with the mental health system before the age of 15 was noted among 20 (15%). There had not been a single suicide since the program's inception. The number of emergency visits during treatment was 5.1±9.0, and hospital admissions averaged 1.8±2.0, with a mean length of stay of 18.3±14.0 days. Many persons (N=66, 51%) lived in supervised residences during treatment, and 42 (32%) lived independently, 16 (12%) resided with family, and six (5%) lived at other facilities. Forty persons (31%) were evicted from a residence during treatment. Most (N=122, 94%) were unemployed during treatment.

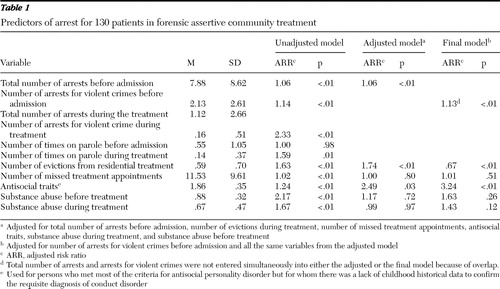

The risk of arrest during treatment by type of crime (violent or nonviolent), episodes of parole, evictions for residential placement, reported substance abuse, and antisocial traits are presented in Table 1 . The final model included data for all persons in the sample and revealed three significant (p<.01) risk factors: history of arrests for violent crimes before treatment, eviction from residential placement during treatment, and presence of antisocial traits. Most (N=83, 64%) persons were not arrested during treatment, but 22 (17%) had a single arrest and 25 (19%) had two or more incidents of arrest. Demographic variables were not significant on bivariate analysis and were excluded from the model.

|

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine predictors of criminal recidivism among patients receiving FACT. Our results are consistent with the research literature demonstrating that criminal behavior among persons with serious mental illnesses is related to risk factors shared with the general population ( 13 ). Although other studies examining similar populations have identified substance abuse as a chief risk factor ( 14 ), surprisingly, our study did not. A lack of heterogeneity for substance use in our sample, however, may explain this outcome. That drug use itself is an illegal act strongly suggests that it increases the likelihood of arrest within this population and warrants heightened attention for mitigating criminal justice risk. Limitations of this study include the lack of a comparison sample, lack of measures of symptom severity, and use of a retrospective study design.

Despite these shortcomings, the presence of risk factors that are both identifiable and modifiable among patients receiving FACT has important implications for development of this intervention approach. FACT is based on the ACT model, an ideal platform to adapt for patients with serious mental illness with a criminal history because it targets certain risk factors for recidivism. ACT model fidelity criteria include program elements that directly target psychosis, co-occurring substance use, and unemployment ( 15 ). However, ACT's lack of effectiveness in preventing arrest suggests that adaptations are necessary to target additional variables that have been associated with criminal recidivism both in this study and in the research literature. These include residential instability, antisocial personality features, high levels of treatment nonadherence, and the tendency of high-risk patients to fall through the cracks between the mental health and criminal justice systems ( 4 ).

According to a national study of FACT, existing programs have implemented some ACT model adaptations more commonly than others. Lamberti and colleagues ( 8 ) found that all programs actively partnered with judges, probation officers, or parole officers—an adaptation that can both promote treatment adherence through the use of legal leverage and ensure continuity of care. Half of the programs also incorporated a residential treatment component, but only one program was identified that incorporated cognitive-behavioral interventions to target and restructure criminal thinking.

Consistent with the emergent literature regarding FACT participants, our results suggest that FACT model development may benefit from incorporation of several intervention components that may promote treatment adherence and community tenure. These include development of active partnerships with criminal justice organizations to aid in identification of at-risk participants, support for transition from incarceration to community settings, and integration of clinical and legal approaches to adherence. Incorporation of residential services can further assist in fostering successful transitions from correctional settings as well as promoting community tenure. In addition, further incorporation of treatment approaches for persons with co-occurring disorders and of evidence-based cognitive-behavioral treatments for antisocial behaviors appear to be indicated given the high prevalence of substance use and antisocial personality features among offenders with mental illness.

FACT programs are emerging across the United States with substantial variability in how they are structured and implemented ( 8 , 9 , 10 ). Research is needed to develop and test a standardized model of intervention. There is a lack of available outcome data to guide FACT model development. Although three studies have reported favorable outcomes associated with FACT programs ( 8 ), all have lacked a control group. In the absence of a clearly defined model, the results of this study suggest that patients who receive FACT have modifiable risk factors that can serve as targets to guide future intervention efforts.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank CARES (Committee to Aid Research to End Schizophrenia), Pittsford, New York, for its support.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Lamb HR,Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483–492, 1998Google Scholar

2. Ditton PM: Bureau of Justice Statistics Report: Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 1999Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders: 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515–2523, 2005Google Scholar

4. Lamberti JS: Understanding and preventing criminal recidivism among adults with psychotic disorders. Psychiatric Services 58:773–781, 2007Google Scholar

5. Stein LI, Santos AB: Assertive Community Treatment of Persons With Severe Mental Illness. New York, Norton, 1998Google Scholar

6. Phillips SD, Burns BJ, Edgar ER, et al: Moving assertive community treatment into standard practice. Psychiatric Services 52:771–779, 2001Google Scholar

7. Bond GR, Drake RE,Mueser KT, et al: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141–159, 2001Google Scholar

8. Lamberti JS, Weisman R, Faden DI: Forensic assertive community treatment: preventing incarceration of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:1285–1293, 2004Google Scholar

9. Cuddeback GS, Morrissey JP, Cusack KJ: How many forensic assertive community treatment teams do we need? Psychiatric Services 59:205–208, 2008Google Scholar

10. Vitacco MJ, Van Rybroek GJ, Erickson SK, et al: Developing services for insanity acquittees conditionally released into the community: maximizing success and minimizing recidivism. Psychological Services 5:118–125, 2008Google Scholar

11. Lamberti JS, Weisman R, Schwarzkopf S, et al: The mentally ill in jails and prisons: towards an integrated model of prevention. Psychiatric Quarterly 72:63–77, 2001Google Scholar

12. Prevention of jail and hospital recidivism among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:1477–1480, 1999Google Scholar

13. Bonta J, Law M, Hanson K: The prediction of criminal and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 123:123–142, 1998Google Scholar

14. Erickson SK, Rosenheck, RA, Trestman RL, et al: Risk of incarceration between cohorts of veterans with and without mental illness discharged from inpatient units. Psychiatric Services 59:178–183, 2008Google Scholar

15. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 86:216–232, 1998Google Scholar