Subtypes of Clients With Serious Mental Illness and Co-occurring Disorders: Latent-Class Trajectory Analysis

Co-occurring substance use disorders are a frequent and clinically significant complication of serious mental illness. Approximately 50% of adults with serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, are affected in their lifetimes by substance use disorders ( 1 , 2 ). Compared with individuals with serious mental illness alone, those with co-occurring substance use disorders have more serious adverse outcomes, including higher rates of relapse, hospitalization, homelessness, interpersonal violence, incarceration, HIV infection, and hepatitis C infection ( 3 , 4 ).

Although the short-term outcomes related to co-occurrence are extremely serious, longer-term outcomes are heterogeneous. Many clients with co-occurring disorders achieve remission of their substance use disorders ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ), often in relation to combined or integrated mental health and substance abuse treatments ( 9 ). As yet, there is no clinical typology that clarifies this heterogeneity in terms of treatment response or guidance for needed treatments.

Psychopathologists, beginning with Kraepelin's ( 10 ) separation of psychotic disorders into dementia praecox and manic depression over a century ago, have recognized the clinical and theoretical importance of distinguishing among different longitudinal trajectories of illness. The attempt to identify theoretical and practical groups according to longitudinal patterns continues to be an active area of research on psychopathology ( 11 , 12 ).

The long-term course of substance use disorders in the general population tends, on average, toward decreased use of substances and improvement of substance-related problems over time ( 13 , 14 , 15 ). Average course may, however, be misleading in that it reflects a mixture of many individual courses and may obfuscate the trajectories of important subgroups for which course and treatment differ substantially. Recognizing the limitation of focusing on group mean course, statisticians have suggested identifying multiple courses of illness ( 16 ). Recently, latent-class trajectory models ( 17 , 18 ) have been used to study the course of various types of psychopathology, including the early developmental course of substance use disorders ( 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ). These methods are particularly promising for studying psychiatric illnesses because they offer the potential to identify subgroups based on a key outcome (remission, for example) that can then be characterized by clinically meaningful profiles, treatment responses, and even genomics. Baseline as well as time-varying covariates could yield important insights regarding differential vulnerability, resilience, and effective treatments for these groups.

On the basis of previous research ( 15 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ) as well as clinical observations, we hypothesized three groups: clients who are easy to engage, are motivated for treatment, form strong therapeutic relationships, have relatively mild forms of substance use disorders, and have positive psychosocial supports; clients with more severe substance use disorders and fewer psychosocial supports who are nevertheless able to engage in treatment over time; and clients who have histories of conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, severe substance dependence, a lack of family supports, criminally involved social networks, and difficulty forming treatment relationships.

In two previous studies based on the New Hampshire Dual Diagnosis Study, we showed that as a group, clients with co-occurring disorders tended to improve over ten years ( 29 ) and that their longitudinal course could be modeled by latent-class trajectory analysis ( 30 ). In the latter article, we illustrated the statistical approach by modeling remission from a substance use disorder without attempting to characterize group profiles or to identify course markers. In this article, we identify latent trajectory classes in relation to two conceptualizations of substance abuse recovery: stage of treatment and abstinence. These concepts represent two common perspectives on co-occurring disorders treatment: harm reduction and abstinence. We also characterize the identified groups by baseline characteristics and participation in treatments. Finally, we consider the clinical implications of the typology.

Methods

Procedures

The New Hampshire Dual Diagnosis Study is a prospective, long-term follow-up of clients with serious mental illness (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder) and co-occurring substance use disorders (abuse of or dependence on alcohol, drugs, or both, excluding nicotine). Details of recruitment, attrition, and both short-term and long-term follow-up are provided in several previous reports ( 29 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ). Briefly, participants were recruited from seven of New Hampshire's ten community mental health centers between 1989 and 1992, were assessed at baseline and reassessed annually with the use of standardized instruments, and were involved for three years in a randomized controlled trial of case management models. Experimental results showed considerable crossover of treatments and few experimental effects after three years. Participants were subsequently released from their experimental conditions, followed in services as usual, and reassessed annually for the next seven years. The study was approved annually by the Dartmouth and New Hampshire institutional review boards, and participants provided written informed consent before each annual interview.

We conducted the analysis in three steps. First, we defined substance abuse recovery as two outcomes: stage of treatment (engagement, persuasion, active treatment, and relapse prevention) ( 35 ) or stable abstinence ( 36 ), with both ratings based on six-month point prevalence. Second, we used latent-class trajectory analysis to identify groups ( 37 ). Third, we profiled the predominant trajectory groups in terms of clinically relevant baseline characteristics and treatment participation.

Longitudinal study group

The study group initially included 223 participants who met the following criteria: long-term psychotic illness (schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder) or bipolar disorder, an active substance use disorder (abuse of or dependence on alcohol and other drugs within the past six months); resident of New Hampshire; absence of mental retardation; and able and willing to give informed consent. Compared with clients in a statewide survey, the study group participants were more likely to be young, male, and employed, and they were of course far more involved with alcohol and drugs ( 32 ).

Measures

Substance abuse recovery. The co-occurring disorders field continues to be divided in terms of harm reduction versus abstinence philosophies ( 38 ). We therefore examined substance abuse recovery both as a stagewise concept (stage of treatment) and as stable abstinence. To make annual ratings, we combined interview, laboratory, and clinical rating data, all based on six-month point prevalence. The interviews included the Time-Line Follow-Back ( 39 ) to assess days of alcohol and drug use over the previous six months and the substance use sections of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) ( 40 ) to assess alcohol and drug problem severity over the past 30 days. Urine toxicology screens were conducted at each interview in our laboratory (EMIT enzyme immunoassay; Syva-Behring). Outreach clinicians (case managers) rated substance use over the previous six months using three clinician rating scales: the Alcohol Use and Drug Use scales (AUS and DUS) and the Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS) ( 35 ). After five years, we discontinued the clinical ratings because many participants were no longer involved in treatment, and our analyses indicated that the clinical ratings no longer added to the consensus ratings.

To establish consensus ratings of stage of treatment and of abstinence over the previous six months, two independent raters considered all available data (interview rating scales, clinician ratings, and urine drug screens) to establish separate ratings on the SATS for stage of treatment and on the AUS and DUS for abstinence. The SATS is an 8-point scale based on early and late stages of engagement, persuasion, active treatment, and relapse prevention. The AUS and DUS are 5-point scales based on DSM-III-R criteria for severity of disorder: 1, abstinence; 2, use without impairment; 3, abuse; 4, dependence; and 5, severe dependence. A rating of abstinence required no evidence of use from all data sources. To determine interrater reliabilities, researchers independently rated a randomly selected subgroup (433 observations of 65 participants). Intraclass correlation coefficients were .93 on the SATS and .94 on both the AUS and DUS. All discrepancies were resolved to establish consensus ratings.

Baseline vulnerability markers. Psychiatric interviewers established diagnoses of co-occurring psychotic illness, substance use disorder, and antisocial personality disorder using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R ( 36 ) before study entry. In addition to the measures described above, the research interview included items from the Uniform Client Data Inventory ( 41 ) to assess demographic information and the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ( 42 ) to rate psychiatric symptoms.

Treatment participation. Participants reported on their medication use at each interview, and we confirmed clozapine use through medical records. Treatment alliance was assessed from client and clinician perspectives at the two-year follow-up with the Working Alliance Inventory ( 43 ). Self-help involvement (such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous) was determined from participants' self-report. Participation in treatment (including hours of case management, physician visits, and partial hospitalization) during the first three years was determined via management information system data from the mental health centers. Days living in group homes, residential dual-diagnosis treatment programs, or psychiatric hospitals were calculated from the Residential Time-Line Follow-Back Inventory ( 44 ). Episodes of alcohol and drug treatment were determined from the ASI, and engagement in substance abuse treatment was determined from SATS ratings.

Statistical analyses

To identify latent trajectory groups on substance abuse recovery over ten years, we used a group-based modeling approach, also called latent-class growth analysis ( 17 ). The analysis was conducted with SAS Proc TRAJ software ( 45 ) and was replicated with Mplus software ( 17 ). The group-based modeling approach assumes that mixtures of groups exist in the study population in terms of their trajectories on particular outcomes. The objective is to identify groups, or latent classes, with distinctive trajectories and to classify individuals with similar trajectories into the same groups. Actual group membership is unknown, and predicted group assignment is based on the estimated model parameters. Variability in growth trajectories is not modeled at the individual level but is reflected at the latent trajectory class level. The shapes of the group trajectories are generally described by a polynomial function of time (for example, a linear or quadratic equation). We have explained this approach mathematically elsewhere ( 30 ).

To examine differences between trajectory groups, we compared two clinically relevant pairs of groups on the basis of a priori hypotheses. For the baseline vulnerability markers and treatment participation variables, we conducted independent-groups t tests or chi square tests. We used a significance level of .01 in order to control for type I errors while maintaining a reasonable level of statistical power.

Although group-based modeling approaches do not automatically exclude persons with missing data, we restricted our longitudinal analyses to the 177 participants active at the ten-year follow-up. Replication of the latent-class trajectory analyses with the full sample of 223 yielded the same four trajectory groups with similar longitudinal patterns for each group. However, we based the group-difference analyses on the 177 active participants, because participants lost to long-term follow-up were missing data for many covariates from the first three years.

Results

The sample of 223 participants at baseline was predominantly male (N=165, 74%), Caucasian (N=214, 96%), young (mean±SD age 34.0±8.5 years), and unmarried (N=198, 89%). Fifty-three percent (N=119) had a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia, 22% (N=50) schizoaffective disorder, and 24% (N=54) bipolar disorder. All were diagnosed as having co-occurring substance use disorders: 75% had an alcohol use disorder (N=167) and 41% had at least one drug use disorder (N=91). Cannabis was the most commonly abused drug at baseline, followed by cocaine; other drugs were abused by only a small number of participants. During the year before baseline, 9% were incarcerated at least once (N=20), 58% were hospitalized at least once (N=129), and 26% were homeless for at least one night (N=58).

Over ten years, 46 participants (21%) were lost to follow-up: 19 (9%) participants died, and 27 (12%) were lost to dropout, refusal, or inability to locate. Thus 177 individuals (79%) of the total, or 87% (N=194) of those living, were actively participating in the study at ten years. Those lost to attrition did not differ from active participants on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

Latent trajectory groups

Identifying latent trajectory groups within an average pattern requires a dynamic model-fitting process with maximum likelihood estimation to determine the optimal number of groups and to define the shape of the trajectory for each group simultaneously ( 46 ). We began with a one-group model and continued our process until we had fitted a five-group model. We examined each model with the Bayesian information criterion, which is widely recommended as the model-fit index in this context. A higher value corresponds to a better model fit ( 17 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 49 ). The four-group solution yielded the largest Bayesian information criterion values for recovery outcomes, both in terms of number of participants and number of observations.

Figure 1 shows the latent-class trajectory groups based on stage of treatment (top) and on abstinence (bottom). Group sizes were similar for both analyses, and there was a high degree of concordance, with 74% (N=131) of participants classified in the same group in both analyses. For both outcomes, the no-recovery group was the largest (N=76 for treatment stage and 81 for abstinence), followed by the late-recovery group (N=60 for treatment stage and 53 for abstinence) and then the early-recovery group (N=31 for treatment stage and 30 for abstinence). The unstable-recovery group was quite small in both analyses. Defining recovery as stage of treatment showed the late-recovery group making progress from year 1 and thereafter, whereas abstinence did not emerge for this group until the sixth year. Otherwise, the temporal patterns were similar for both outcomes.

Latent-class trajectory group profiles

To examine the association between group membership and relevant covariates, we used planned comparisons to focus on clinically meaningful contrasts of the major trajectory groups. We eliminated the unstable-recovery group, which contained too few participants for statistical analyses.

First, we compared the early-recovery group with the combined no-recovery and late-recovery groups. Our hypotheses were that early recovery would be related to less severe substance use disorders (alcohol and drugs), less antisocial personality disorder, greater psychosocial stability (absence of homelessness and incarceration, greater family support, and more employment), and better treatment alliance. We had no specific hypotheses about demographic, symptom, and treatment variables. Because the trajectory for the early-recovery group separated from the trajectories for the other two groups during the first year, understanding the predictors of early recovery might lead to efficient service allocation for these individuals.

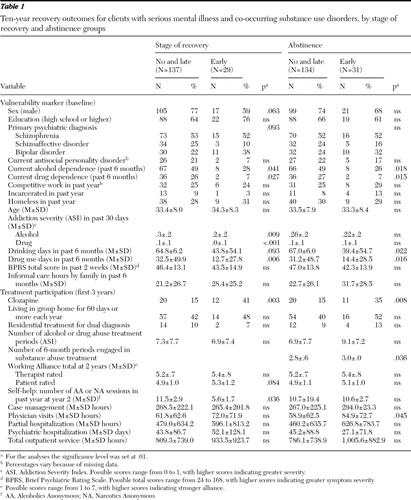

As shown in Table 1 , the early-recovery group differed from the combined no-recovery and late-recovery groups primarily in terms of having less severe substance use disorders. Several measures of severity of substance abuse at baseline were significant correlates of recovery, when defined as stage of treatment (SATS score) (three of six measures of baseline substance use at p<.01). None were significant at p<.01 for recovery, as defined by abstinence, although four of six measures of baseline substance use were significant at p<.05. All other hypotheses (absence of antisocial personality disorder, psychosocial stability, and treatment alliance) were not confirmed. One unhypothesized treatment variable, clozapine use, was associated with early recovery.

|

Second, we compared the late-recovery and the no-recovery groups. Identifying these groups early on might lead to better risk adjustment and to differential treatments. Our hypotheses were that late recovery would be related to less antisocial personality disorder, greater psychosocial stability (absence of homelessness and incarceration, greater family support, and more employment), better treatment alliance, and greater participation in all treatments.

As shown in Table 2 , these two groups differed on few covariates. Our hypotheses on antisocial personality, psychosocial stability, and treatment alliance were not supported. The late-recovery group scored better on almost all measures of treatment, but the only difference that was clearly significant was participation in dual-diagnosis residential programs.

|

Discussion

Four co-occurring disorders groups emerged from the data according to patterns of recovery over ten years, whether stage of substance abuse recovery or abstinence was the outcome of focus. The concordance of the four-group solutions indicates that differences between the harm reduction and abstinence perspectives across ten years may be more philosophical than empirical. Whereas the SATS was more sensitive to changes in the middle years, both outcomes converged by the end of ten years. One group was too small to analyze statistically, but the three major groups—early, late, and no recovery—showed clinically meaningful differences. Below we discuss the differences among the three groups that emerged regardless of whether the groups were derived from analysis of the stage of substance abuse recovery or abstinence outcome. As shown in Tables 1 and 2 , there were other significant differences among the groups that depended on which outcome was used. These outcome-specific findings have implications for clinical practice, as well as for further research, but they await replication.

The early-recovery group clients had less severe substance use disorders, in accord with many studies of substance abuse treatment and formulations of differential risk ( 50 ). Early-recovery clients engaged quickly in treatment, achieved abstinence within the first year, and remained abstinent for years. Use of clozapine was remarkably common (over one-third) for this group. Our measures of therapeutic alliance, antisocial personality disorder, and psychosocial stability did not differentiate these clients from others, which may indicate problems with our measures, hypotheses, or both. Previous research has identified the potential of clozapine ( 51 ), but this was the first indication that persons who have a response to clozapine have milder forms of substance abuse.

The late-recovery group emerged early in terms of stages of treatment but did not begin to achieve stable abstinence until the sixth year of the study. This finding supports the view that progress in terms of stage of treatment is an important measure of early recovery, especially in short-term studies with only one or two years of follow-up ( 52 ). It also supports the long-term, client-centered nature of services for co-occurring disorders ( 53 ).

Most of our hypotheses regarding differences between the late-recovery and no-recovery groups were not supported. Although the late-recovery clients used more treatments of various types, only residential dual-diagnosis treatment emerged as a strong covariate. This finding reinforces other research showing that residential dual-diagnosis treatment is particularly effective for clients who have difficulty achieving abstinence in the first year of treatment ( 54 ), but it casts doubt on theories regarding therapeutic alliance, antisocial personality disorder, and other treatment modalities.

The no-recovery group was interesting for several reasons. First, by proportion it was the largest group. Second, the lack of recovery referred only to substance use disorders. As we showed elsewhere ( 29 ), recovery on other dimensions is minimally related to substance use, and these clients often achieve significant recovery in terms of employment and other goals. Third, lack of substance abuse recovery in the first years of treatment should stimulate attempts to try not only dual-diagnosis residential treatment but also innovative treatments of other kinds. Many substance abuse interventions, such as family therapy, intensive outpatient treatment, disulfiram, naltrexone, and contingency management, have not been studied extensively in this population ( 9 ).

This exploratory study had several limitations: small study group size, selection bias (due to participants who initially entered a randomized controlled trial), rural and small urban settings, naturalistic follow-ups, and lack of racial-ethnic diversity. In addition, ratings of abstinence from alcohol and drugs were based on the last six months of each year.

Conclusions

Despite these weaknesses, the study uniquely provided ten years of prospective data on substance abuse recovery for a cohort of individuals with serious mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Finally, our subtypes should be viewed as hypothesis-generating: the trajectory groups and their profiles should be examined in independent samples.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant RO1-MH59383from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17–31, 1996Google Scholar

2. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 264:2511–2518, 1990Google Scholar

3. Buckley FP: Prevalence and consequences of the dual diagnosis of substance abuse and severe mental illness. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67(suppl 7):5–9, 2006Google Scholar

4. Drake RE, Brunette MF: Complications of severe mental illness related to alcohol and other drug use disorders, in Recent Developments in Alcoholism, vol 14, Consequences of Alcoholism. New York, Plenum, 1998Google Scholar

5. Cuffel BJ, Chase P: Remission and relapse of substance use disorder in schizophrenia: results from a one-year prospective study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:342–348, 1994Google Scholar

6. Dixon L, McNary S, Lehman AF: Remission of substance use disorder among psychiatric inpatients with mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:239–243, 1998Google Scholar

7. Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, et al: Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:57–67, 1990Google Scholar

8. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Clark RE, et al: The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:42–51, 1996Google Scholar

9. Drake RE, O'Neal E, Wallach MA: A systematic review of research on interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 34:123–138, 2008Google Scholar

10. Kraepelin E: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia [in German]. New Delhi, Science History Publications, 1990, originally published 1899Google Scholar

11. Annis H: Patient-treatment matching in the management of alcoholism, in Problems of Drug Dependence, 1988: Proceedings of the 50th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Inc. Edited by Harris LS. NIDA Research Monograph 90. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1988Google Scholar

12. Fenton WF, Mosher LR, Matthews SW: Diagnosis of schizophrenia: a critical review of current diagnostic systems. Schizophrenia Bulletin 7:452–476, 1981Google Scholar

13. Hser Y, Powers AD: A 24-year follow-up of California narcotics addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:577–584, 1993Google Scholar

14. Simpson DD, Joe GW, Lehman WEK, et al: Addiction careers: etiology, treatment, and 12-year follow-up procedures. Journal of Drug Issues 16:107–121, 1986Google Scholar

15. Vaillant GE: Natural History of Alcoholism Revisited. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1995Google Scholar

16. Estes WK: The problem of inference from curves based on group data. Psychological Bulletin 53:134–140, 1956Google Scholar

17. Muthen BO, Muthen LK: Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 24:882–891, 2000Google Scholar

18. Nagin D: Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods 4:139–157, 1999Google Scholar

19. Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Wood PK: Trajectories of concurrent substance use disorders: a developmental, typological approach to comorbidity. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 24:902–913, 2000Google Scholar

20. Schulenberg JE, Merline AC, Johnston LD, et al: Trajectories of marijuana use during the transition to adulthood: the big picture based on national panel data. Journal of Drug Issues 2:255–280, 2005Google Scholar

21. Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, et al: Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: a comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. Journal of Drug Issues 2:307–332, 2005Google Scholar

22. Chung TA, Maisto SA, Cornelius JA, et al: Joint trajectory analysis of treated adolescents; alcohol use and symptoms over 1 year. Addiction Behavior 30:1690–1701, 2005Google Scholar

23. Alverson H, Alverson M, Drake RE: Social patterns of substance use among people with dual diagnoses. Mental Health Services Research 3:3–14, 2001Google Scholar

24. Drake RE, Wallach MA, Alverson HS, et al: Psychosocial aspects of substance abuse by clients with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190:100–106, 2002Google Scholar

25. Cloninger CR: Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science 236:410–416, 1987Google Scholar

26. Crocker AG, Mueser KT, Drake RE, et al: Antisocial personality, psychopathy, and violence in persons with dual disorders. Criminal Justice and Behavior 32:452–476, 2005Google Scholar

27. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Ackerson TH, et al: Antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder, and substance abuse in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 106:473–477, 1997Google Scholar

28. Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD, Drake RE, et al: Conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and substance use disorders in schizophrenia and major affective disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 60:278–284, 1999Google Scholar

29. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Xie H, et al: Ten-year recovery outcomes for clients with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:464–473, 2006Google Scholar

30. Xie H, Drake RE, McHugo GJ: Are there distinctive trajectory groups in substance abuse remission over 10 years? An application of the group-based modeling approach. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 33:423–432, 2006Google Scholar

31. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Xie H, et al: Three-year outcomes of long-term patients with co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorder. Biological Psychiatry 56:749–756, 2004Google Scholar

32. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE, et al: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68: 201–215, 1998Google Scholar

33. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Teague GB, et al: Fidelity to assertive community treatment and client outcomes in the New Hampshire dual disorders study. Psychiatric Services 50:818–824, 1999Google Scholar

34. Xie H, McHugo GJ, Helmstetter BS, et al: Three-year recovery outcomes for long-term patients with co-occurring schizophrenic and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Research 75:337–348, 2005Google Scholar

35. Drake RE, Mueser KT, McHugo GJ: Clinician rating scales: Alcohol Use Scale (AUS), Drug Use Scale (DUS), and Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS), in Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Edited by Sederer LI, Dickey B. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1996Google Scholar

36. Spitzer RL, William JB, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM III-R: Patient Version (SCID-P, 9/1/89 version). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1988Google Scholar

37. Nagin D: Group-Based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 2005Google Scholar

38. Denning P: Practicing Harm Reduction Psychotherapy: An Alternative Approach to Addictions. New York, Guilford, 2000Google Scholar

39. Sacks J, Drake RE, Williams VF, et al: Utility of the Time-Line Follow-Back to assess substance use among homeless adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:145–153, 2003Google Scholar

40. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Google Scholar

41. Tessler R, Goldman H: The Chronically Mentally Il: Assessing Community Support Programs. Cambridge, Mass, Harper and Row, 1982Google Scholar

42. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:594–602, 1986Google Scholar

43. Horvath AO, Greenberg L: The Development of the Working Alliance Inventory. New York, Guilford, 1986Google Scholar

44. Tsemberis S, McHugo GJ, Williams V, et al: Measuring homelessness and residential stability: the Residential Time-Line Follow-Back Inventory. Journal of Community Psychology 35:29–42, 2007Google Scholar

45. Jones B, Nagin D, Roeder K: A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods and Research 29:374–393, 2001Google Scholar

46. Lennon MC, McAllister W, Kuang L, et al: Capturing intervention effects over time: reanalysis of a critical time intervention for homeless mentally ill. American Journal of Public Health 95:1760–1766, 2005Google Scholar

47. Collins LM, Fidler PL, Wugalter SE, et al: Goodness-of-fit testing for latent class models. Multivariate Behavior Research 28:375–389, 1993Google Scholar

48. Hagenaars J, McCutcheon A: Applied Latent Class Analysis Models. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 2002Google Scholar

49. Magidson J, Vermunt J: Latent class models, in Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Edited by Kaplan D. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 2004Google Scholar

50. Cloninger CR: Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science 236: 410–416, 1987Google Scholar

51. Green AI, Burgess ES, Dawson R, et al: Alcohol and cannabis use in schizophrenia: effects of clozapine vs risperidone. Schizophrenia Research 60:81–85, 2003Google Scholar

52. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Brunette MF, et al: Enhancing validity in co-occurring disorders treatment research. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:655–665, 2006Google Scholar

53. Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, et al: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders: A Guide to Effective Practice. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

54. Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Drake RE: A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review 23:471–481, 2004Google Scholar