Posttraumatic Stress Among Hospitalized and Nonhospitalized Survivors of Serious Car Crashes: A Population-Based Study

Recent reviews have highlighted the increasing global burden of road traffic injuries while acknowledging methodological difficulties in estimating the incidence of disabling nonfatal sequelae related to these injuries ( 1 ). Researchers have attributed the widely divergent estimates of posttraumatic stress among survivors of motor vehicle crashes to several factors, including selected clinic-based study populations, varying outcome measures and follow-up periods, and idiosyncratic litigation and compensation schemes ( 2 , 3 ).

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of posttraumatic stress among survivors of serious injury-producing car crashes in Auckland, New Zealand. Subgroups of interest included hospitalized drivers and passengers as well as nonhospitalized drivers. The state-funded "no fault" injury compensation system covers all residents regardless of their age, occupation, liability, and socioeconomic or insurance status.

Methods

This population-based prospective cohort study was designed to recruit all hospitalized car occupants (passengers and drivers) as well as nonhospitalized drivers involved in crashes that resulted in hospital admission of at least one occupant. The study covered all such crashes in the Auckland region (population approximately one million) between October 1998 and July 1999. As described in detail elsewhere ( 4 ), we excluded individuals aged less than 16 years, those unable to provide informed consent (for example, those with significant cognitive problems), and those who survived fatal crashes or experienced further crashes during the follow-up period (because of the anticipated response burden and changes in exposure status). The Regional Ethics Committee approved the study. After complete description of the study, participants gave informed consent.

Of the 299 drivers and 96 passengers who met the study eligibility criteria, 209 (70%) and 59 (61%), respectively, completed both five- and 18-month interviews by telephone or, if necessary, in person. Compared with participants retained in the study, those lost to follow-up were younger and more likely to be male, to be single, to report hazardous drinking habits at recruitment, and to move residence frequently.

Information collected at recruitment (usually within 48 hours of the crash) included self-reported sociodemographic data; presence of hazardous drinking patterns, which was defined as a score ≥8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Inventory Test ( 5 ); marijuana or other recreational drug use; and a history of psychiatric treatment. Because of diagnostic difficulties related to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and particular challenges with telephone interviews, we obtained self-reported information about the presence or absence of posttraumatic stress using the Impact of Event Scale (IES) ( 6 ) at five and 18 months after the crash. The 15 items were scored by using standard criteria. Possible scores on the IES range from 0 to 75, with higher scores indicating greater levels of intrusive thoughts or avoidance symptoms. We used a cutoff score of 27 to define significant posttraumatic stress based on the findings of a recent validation study ( 7 ). Other variables included in this analysis were scores on the Short Form-36 (SF-36) ( 8 ), a two-item case-finding instrument for depression ( 9 ), and a global health transition indicator that ascertained whether participants considered their overall health at 18 months to be worse, the same, or better than before the crash.

We used chi square tests to compare the prevalence of significant stress by sociodemographic characteristics, alcohol and drug use, and psychiatric history. Pearson product-moment correlations determined correlations between posttraumatic stress at 18 months and the presence of depressive symptoms, the SF-36 mental health subscale score, and participants' impression of their overall health since the crash. All analyses were conducted using SAS release 9.1.

Results

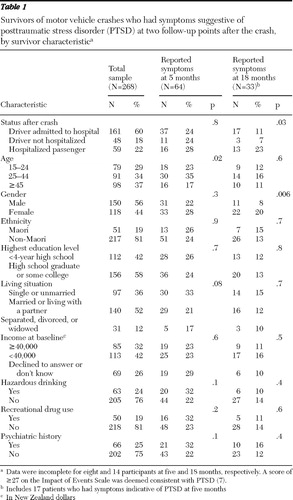

The mean±SD overall IES score among participants was 16.2±15.9 at five months and 8.7±13.7 at 18 months. Levels of posttraumatic stress suggestive of PTSD (IES score ≥27) were reported by 64 participants (25%) at five months and by 33 (13%) at 18 months ( Table 1 ). Seventeen participants (6%) experienced significant levels of stress at both five and 18 months. As shown in Table 1 , about a fourth of hospitalized passengers and drivers and a similar proportion of drivers who were not hospitalized after the crash reported an IES score ≥27 at five months. At 18 months the proportion of hospitalized passengers who reported significant levels of stress remained much the same, whereas the proportions of drivers with significant stress were smaller. Overall, female survivors were significantly more likely than male survivors to report an IES score ≥27 at 18 months (p=.006).

|

At 18 months, an IES score ≥27 was positively correlated with respondents' perception that their overall health was worse than their health before the crash (r=.15, p<.01), with lower scores on the SF-36 mental health subscale (r=.32, p<.001), and with symptoms suggestive of depression (r=.19, p=.003). Twelve survivors (36%) who had an IES score ≥27 screened positive at 18 months, and 12 (27%) who screened positive for depression had an IES score ≥27.

Discussion and conclusions

This is one of a few studies that used a population-based sample of survivors to estimate the prevalence of symptoms consistent with PTSD after motor vehicle crashes. To our knowledge, it is also the only study from a country with a "no fault" injury compensation scheme, which would have reduced the influence of claim-related concerns ( 10 ).

The main limitation of our study is the likelihood that the prevalence of posttraumatic stress was underestimated because of the exclusion of survivors of fatal crashes and passengers who were not admitted to the hospital when the driver was. Despite the low attrition rate compared with other studies in this field, psychological morbidity experienced by participants who were interviewed may have differed from that experienced by survivors who were not interviewed. We assessed symptoms indicative of PTSD by use of a standardized self-report instrument rather than by a diagnostic interview. Although the IES does not identify hyperarousal symptoms, the psychometric properties of the IES compare well with DSM-IV -based instruments ( 11 , 12 ).

A cohort study of 546 participants from the Oxford region found the prevalence of PTSD, as determined by the Posttraumatic Stress Symptom Scale, to be 23% at three months, 17% at one year, and 11% at three years ( 10 ). Although the Oxford study involved emergency department attendees, our study found similar levels of PTSD symptoms among drivers who were and were not hospitalized immediately after the crash. This suggests that significant levels of psychopathology may occur among crash survivors who do not have injuries that require medical attention.

Our study was not designed—and did not have sufficient power—to explore predictors of PTSD. However, being female increased the risk of posttraumatic stress, a finding consistent with previous research ( 10 ). Differences by age group were apparent but did not persist at 18 months. Factors that predicted persistent symptoms of PTSD for a year or more identified in previous research include unresolved medical, financial, litigation, or compensation problems; peritraumatic dissociation and thought suppression; a history of psychological problems before the crash; alcohol abuse; and increased levels of threat and vulnerability at the time of the crash ( 10 , 13 , 14 ). The latter may explain the higher proportion of passengers (compared with drivers) reporting stress symptoms in our study, although our data were insufficient to investigate this. Because the accident compensation scheme in New Zealand covers personal injury for all residents, the influence of litigation could not be investigated in this study. The differential impact of litigation and compensation schemes in contexts where these operate requires further investigation.

In a study of 233 survivors followed up one to two years after a motor vehicle crash ( 13 ), those with chronic PTSD commonly reported symptoms consistent with major depression (53%), a mood disorder (62%–68%), or generalized anxiety disorder (26%)—levels of comorbidity that may reflect higher levels of psychopathology among treatment-seeking survivors ( 10 , 13 ). In our study, which was not restricted to survivors seeking follow-up health care, a third of survivors with significant levels of posttraumatic stress also reported symptoms suggestive of depression and an appreciable deterioration in their overall health since the crash. Effective strategies must address potentially preventable psychological sequelae among hospitalized and nonhospitalized crash survivors.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Ameratunga S, Hijar M, Norton R: Road-traffic injuries: confronting disparities to address a global-health problem. Lancet 367:1533–1540, 2006Google Scholar

2. Blaszczynski A, Gordon K, Silove D, et al: Psychiatric morbidity following motor vehicle accidents: a review of methodological issues. Comprehensive Psychiatry 39:111–121, 1998Google Scholar

3. Kuch K, Cox BJ, Evans RJ: Posttraumatic stress disorder and motor vehicle accidents: a multidisciplinary overview. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 41:429–434, 1996Google Scholar

4. Ameratunga S, Norton R, Connor J, et al: A population-based cohort study of longer-term changes in health of car drivers involved in serious crashes. Annals of Emergency Medicine 48:729–736, 2006Google Scholar

5. Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, et al: AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Geneva, World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, 2001Google Scholar

6. Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine 41:209–218, 1979Google Scholar

7. Coffey S, Gudmundsdottir B, Beck JG, et al: Screening for PTSD in motor vehicle accident survivors using the PSS-SR and IES. Journal of Traumatic Stress 19:119–128, 2006Google Scholar

8. Gandek B, Ware J: Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1993Google Scholar

9. Whooley M, Avins A, Miranda J, et al: Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine 12:439–445, 1997Google Scholar

10. Mayou R, Ehlers A, Bryant B: Posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents: 3-year follow-up of a prospective longitudinal study. Behaviour Research and Therapy 40:665–675, 2002Google Scholar

11. Brewin C: Systematic review of screening instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress 18:53–62, 2005Google Scholar

12. Joseph S: Psychometric evaluation of Horowitz's Impact of Event Scale: a review. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13:101–113, 2000Google Scholar

13. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Freidenberg BM, et al: Two studies of psychiatric morbidity among motor vehicle accident survivors 1 year after the crash. Behaviour Research and Therapy 42:569–583, 2004Google Scholar

14. Beck J, Grant D, Read J, et al: The Impact of Event Scale-Revised: psychometric properties in a sample of motor vehicle accident survivors. Journal of Anxiety Disorder 22:187–198, 2008Google Scholar