Patients' Depression Treatment Preferences and Initiation, Adherence, and Outcome: A Randomized Primary Care Study

Treatments of depression in primary care settings are effective, yet most adults with depression ( 1 ), particularly older ones ( 2 ), do not receive appropriate care. Even when guideline-based treatments are provided, patients often do not fully participate in them. Not surprisingly, therefore, randomized clinical trials have reported substantially poorer outcomes for "intent to treat" than "treatment completer" cohorts ( 3 ), indicating a need for strategies that maximize treatment participation.

A patient's decision not to initiate or complete treatment may stem from disappointment or dissatisfaction with the treatment offered by the clinician. Although medications are the predominant intervention offered to primary care patients with diagnoses of depressive disorders, 50%–86% of those patients prefer a psychosocial intervention ( 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). Thus many patients conceivably refuse treatment offered in primary care because psychotherapy is not an available option.

In psychiatric outpatient settings, treatment preferences have been addressed through "negotiated treatment plans," whereby clinicians elicit patients' preferences and encourage patients to participate in treatment planning. Patients' reports of greater participation in such negotiations have been associated with greater levels of satisfaction, sense of feeling helped, and adherence to treatment plans ( 8 , 9 ). Studies of nonsenior adult patients in the primary care sector have endorsed the value of a negotiated treatment plan and the importance of patients playing active rather than passive roles in formulating it. Such participation enhances the patient's likelihood of initiating treatment and being satisfied with its outcome ( 10 , 11 , 12 ).

Despite these benefits, the few studies examining treatment negotiation and clinical outcome have failed to find a significant association between them. Thus the reports by Bedi and colleagues ( 13 ) and Chilvers and colleagues ( 14 ) of two- and 12-month outcomes, respectively, with the same sample of nonsenior adult primary care patients with depression found generic counseling and antidepressant medication to produce similar improvement rates regardless of whether the patient had personally selected the treatment or been randomly assigned to receive it. However, the study was an unbalanced comparison because only patients refusing the random assignment were then offered their personal preference ( 13 , 14 ). Consequently, the group receiving their preferred treatment was compared with a heterogeneous group of patients. Of the comparison group, some preferred the treatment to which they were randomly assigned, and others did not prefer it but participated in the treatment anyway; either their preferences were not very strong, or the patients tended toward adherence regardless of preference. A related observational study found no differences in clinical outcomes of senior primary care patients who were and were not provided access to their preferred treatment of medication or counseling ( 15 ). The impact of treatment preferences may have been underestimated in these studies, however, because the investigators conceptualized preferences as an either-or condition rather than as existing on a continuum.

Given the inconclusive findings regarding the relationship between treatment preference and clinical outcome, particularly among older adults, we sought to extend the knowledge base by using a variant of the "partially randomized patient-preference design" ( 16 ). Thus we randomly assigned primary care patients experiencing major depression to receive treatment either congruent or incongruent with their primary preference. A particular study aim was to determine whether strength of treatment preferences for antidepressant medication and psychotherapy, more so than sheer congruence of preferences with the assigned treatment, would be associated with treatment initiation, adherence, and short-term outcome. We hypothesized that stronger preferences for an offered treatment would be positively related to treatment initiation, 12-week adherence, and 12- and 24-week depression severity and remission. We also examined whether age (nonsenior adults, aged 21–59, versus seniors aged 60 or older), treatment type, and depression severity moderated the above relationships.

Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Weill Cornell Medical College.

Sample

The study was conducted at Cornell Internal Medical Associates (CIMA), a Manhattan-based academic ambulatory group practice. CIMA physicians referred patients age 21 or older whom they judged as having major depressive disorder and who were not currently receiving either antidepressant medication or psychotherapy. After complete description of the study to the participants, written informed consent was obtained. Patients were informed that if they met study criteria, they would be randomly assigned to receive either antidepressant medication or psychotherapy free of charge for the study's duration. Patients were not informed, however, that random assignment would be based on their stated a priori treatment preferences.

Inclusion criteria consisted of age 21 and over; meeting Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID) ( 17 ) criteria for major depression; scoring higher than 14 points on the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), indicating at least mild depression ( 18 ); ability to speak and understand English; and ability to give informed consent as evaluated by the participant's understanding of the study and its procedures. Exclusion criteria consisted of a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ( 19 ) score less than 24 out of 30 points, indicating probable dementia; dementia diagnosis; history of mania, hypomania, or psychosis; current alcohol or drug abuse or dependence; suicide plan or intention; current receipt of treatment with antidepressant medication or psychotherapy; pregnancy; and inability to attend treatment sessions during CIMA office hours.

Participants meeting eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to receive treatment that was either congruent or incongruent with their previously stated primary treatment preference (see below). Power analyses determined that 60 participants were needed to detect hypothesized adherence and outcome differences. Of the 60 participants recruited between April 2004 and November 2006, 29 were randomly assigned to treatment congruent with and 31 were assigned to treatment incongruent with their stated preference.

Intervention

Study participants were offered either evidence-based antidepressant medication treatment (escitalopram) or brief psychotherapy (interpersonal psychotherapy). The latter option addressed one or more interpersonal problem areas (for example, grief, role transition, interpersonal dispute, and interpersonal deficit) ( 20 ); interpersonal therapy effectively treats adult patients for depression ( 21 ). Participants randomly assigned to psychotherapy were offered, after approval by the primary care physician, 12 weekly in-person interpersonal psychotherapy sessions followed by two telephone sessions at weeks 16 and 20. For participants randomly assigned to antidepressant medication, the study's care manager recommended that the primary care physician prescribe escitalopram 10 mg daily for the 20-week study period. When the physician approved this pharmacotherapy, the care manager met with participants at weeks 1, 4, 8, 12, and 24 to ascertain whether they were taking the medication, monitor adverse side effects, encourage adherence, and assess clinical changes. When participants did not respond to escitalopram at week 4 or beyond, the primary care physician raised the dosage to 20 mg daily on the basis of the care manager's assessment and recommendation. Two care managers, each with more than five years of clinical experience, provided all treatment under the supervision of the principal investigator and the study psychiatrist.

Given the study's aim of determining the impact of treatment preference strength on treatment adherence and outcome, participants received pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy without charge so as to avoid confounding that would be associated with third-party reimbursement schedules.

Participants were free to pursue any additional treatment throughout the study period. Persons assigned to a treatment group who refused treatment or who prematurely terminated treatment were offered referrals for psychiatric services of their choice within or outside the study site.

Measurement of treatment preferences and expectations

Before study randomization, participants' baseline treatment preferences for antidepressant medication, individual or group psychotherapy, combined medication and psychotherapy, herbal remedies, religious or spiritual activities, exercise, or "doing nothing" were rank ordered according to their response to the following question: "Based on your experience and how you feel right now, which of the following treatments would be your first choice, second choice, and third choice?" Although the actual study treatments were limited to either antidepressant medication or individual psychotherapy, we documented participants' preferences for other treatment approaches.

The highest rank order that participants assigned to either of the two study interventions determined their treatment preference and, depending on the group to which they were subsequently randomly assigned, what treatment they were offered (congruent or incongruent with their preference). Congruence of treatment preference with the treatment to which participants were randomly assigned served as the initial predictor variable. Strength of treatment preferences was also assessed before study randomization for any depression treatment ("I want to be treated for my depression at this time with medication or psychotherapy"), for antidepressant medication ("I wish to receive medication for my depression"), and for psychotherapy ("I wish to receive counseling or psychotherapy for my depression") on 5-point Likert scales (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). Strength of treatment preference for the specific treatment to which participants were randomly assigned served as an additional main predictor variable. Treatment expectation—that is, a participant's anticipated likelihood of improvement—was assessed with the participant's response to the following item: "The probability that I will get better with antidepressant medication (or psychotherapy) is [0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, or 100%]."

Randomization

Participants meeting eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to treatment that was either congruent or incongruent with their primary stated treatment preference as described above.

Other baseline measures

Research assistants trained in administering the SCID ( 17 ) assessed major depression and other psychiatric disorders. Diagnoses were assigned after review by the principal investigator. Severity of depression was assessed with the 24-item HRSD ( 18 ). Diagnostic status and presence of psychotic or manic symptoms, suicidal ideation, and alcohol or drug abuse were reported to the participant's primary care physician.

Baseline interviews determined demographic characteristics and history of psychiatric treatment. Cognitive impairment was assessed with the MMSE ( 19 ), and medical burden was assessed with the Chronic Disease Score ( 22 ). Functioning was assessed with the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS-II, 12-item version), which measures six domains: understanding and communicating, getting around, self-care, getting along with others, household and work activities, and participation in society ( 23 ). Social service needs, such as assistance with housing, finances, legal problems, adult protective services, medical coordination, and transportation, were assessed with the 17-item Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE) ( 24 ).

Follow-up measures of treatment

Research assistants collected information about psychotherapy attendance via care manager records and about daily medication use via participants' retrospective reports at weeks 4, 8, and 12. Treatment initiation was defined as taking at least one dose of medication or attending at least one psychotherapy session. Adherence during the initial 12-week treatment period was defined as the proportion of antidepressant medication doses taken out of the 84 prescribed or the proportion of therapy sessions attended of the 12 scheduled ones. This operationally defined approach placed both treatments on relatively comparable adherence scales. At weeks 4, 8, 12, and 24, depression severity was assessed with the HRSD.

Statistical analyses

The nature and strength of participants' treatment preferences are described with percentages, means, and standard deviations. After testing equivalence of participants randomly assigned to congruent versus incongruent treatment on sociodemographic and clinical variables, we performed separate analyses using two main predictor variables: first, congruence versus incongruence of treatment preference with the treatment to which participants were randomly assigned and second, strength of treatment preferences for the assigned treatment. Thus we used Fisher's exact test to examine the impact of congruent treatment on treatment initiation and logistic regression to examine the association of preference strength for the assigned treatment with its initiation. We used linear regression to examine the impact first of congruent treatment and then of preference strength on treatment adherence and on 12- and 24-week HRSD scores after controlling for baseline HRSD score. We used Fisher's exact test and logistic regression to examine the association of congruent treatment and preference strength, respectively, with clinical remission (that is, HRSD score <7 points). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were included as covariates if they were associated at the .05 significance level with any criterion variable. Finally, we examined the moderating effects of age (nonseniors, aged 21–59, versus seniors, aged 60 or older), treatment type (medication versus psychotherapy), and HRSD severity of depression in the above models. SPSS version 14.0 was used to carry out analyses ( 25 ).

Results

Participant population

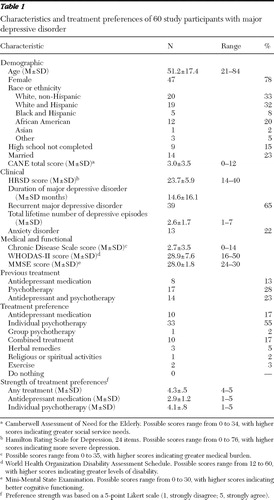

All 60 protocol-eligible patients agreed to enroll. [A CONSORT chart of the selection process is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org. ] Of the 60 who agreed, 38 (63%) were 21–59 years old, and 22 (37%) were 60 or older. The sample of 60 randomly assigned participants was predominantly female and included diverse ethnicities ( Table 1 ). Two-thirds of participants self-identified as members of racial-ethnic minority groups. Participants typically experienced depression of moderate severity, extended duration, and recurrent nature, with 21 (35%) reporting passive suicidal ideation at baseline and 39 (65%) having a history of antidepressant treatment, psychotherapy, or both. Treatment groups did not differ on sociodemographic or clinical variables. Mean baseline HRSD scores for participants assigned to congruent versus incongruent treatment were 22.7±5.3 and 24.6±6.3, respectively. Possible scores range from 0 to 76, with higher scores indicating more severe depression.

|

Of 22 participants with previous antidepressant experience, 14 (64%) agreed or strongly agreed that "the treatment was effective" and 15 (68%) agreed or strongly agreed that "the treatment resulted in troubling side effects or made me more distressed." Of 31 participants with previous psychotherapy experience, 19 (61%) agreed or strongly agreed that "the treatment was effective" and nine (29%) agreed or strongly agreed that "the treatment resulted in troubling side effects or made me more distressed."

Follow-up data on treatment adherence were available for all participants. HRSD 12-week data were available for 26 (90%) participants in the congruent group and 27 (87%) participants in the incongruent group. HRSD 24-week data were available for 25 (86%) congruent group and 24 (77%) incongruent group participants. Participants who dropped out by week 12 had lower rates of treatment adherence throughout the study period compared with those who did not drop out (mean±SD proportion of attended sessions or pills taken .09±.10 versus .67±.36 for participants who were followed; t=4.20, df=58, p<.001). No other variable distinguished dropouts from completers.

Treatment preferences

Ranked treatment preferences are presented in Table 1 . When patient preferences were restricted to either of the two study treatments, 42 (70%) participants selected individual psychotherapy and the remaining 18 (30%) selected antidepressant medication. An analysis of preference strength for the entire sample revealed stronger preferences for psychotherapy than for antidepressants (paired t=5.6, df=58, p<.001). The mean preference strength for psychotherapy was 4.1, signifying "agreement;" in contrast the mean preference strength was 2.9 for antidepressants, indicating "neutral or indifferent." Preference strength for treatments was unrelated to age group.

Participants anticipated greater improvement from psychotherapy (.72±.20) than from antidepressant medication (.49±.30) (paired t=4.4, df=54, p<.001). Again, expected improvement did not differ by age group.

Preference strength and treatment initiation

All 29 participants randomly assigned to treatment congruent with their preference initiated treatment. Only 23 of 31 (74%) of the incongruent group did so (Fisher's exact test=.005).

All eight participants (13% of study participants) who did not initiate treatment had been assigned to receive antidepressant medication. Even though these participants were offered psychotherapy referrals outside of the research protocol, none had pursued such treatment when assessed at periodic follow-ups.

Logistic regression indicated that treatment initiation was associated with stronger treatment preferences (odds ratio [OR]=5.3, 95% confidence interval [CI]=4.3–6.3, df=1, p=.001) ( Figure 1 ) and expectation of improvement from the assigned treatment (OR=2.5, 95% CI=1.9–3.1, df=1, p=.002), but initiation was not associated with any sociodemographic or clinical variable. In a combined model, preference strength was associated with treatment initiation over and above expected improvement (OR=4.4, 95% CI=3.3–5.5, df=1, p=.009). Interaction terms of preference strength by age group (nonseniors versus seniors) and depression severity (HRSD score) were not significant.

Preference strength and treatment adherence

Preference strength for assigned treatment, but not simply congruence, was associated with higher 12-week treatment adherence rates ( β =13.40, p=.002) ( Figure 2 ). Differences in mean±SD adherence rates between participants assigned to psychotherapy (.68±.32) and antidepressant medication (.52±.43) were not significant. No other variables were associated with adherence, although expected improvement from the assigned treatment approached significance ( β =6.65, p=.060). Interaction terms of preference strength by age group (nonseniors versus seniors), treatment type (antidepressant medication versus psychotherapy), and depression severity (HRSD score) were not significant.

Preference strength and outcome

Across groups, mean±SD HRSD ratings at 12 and 24 weeks were 16.4±8.3 (range 3–38) and 16.3±9.9 (range 2–42), respectively. Remission rates (HRSD score <7) at 12 and 24 weeks were 21% (11 of 53) and 29% (14 of 49), respectively.

Congruent treatment was not significantly related to 12- and 24-week HRSD scores in linear regression models controlling for baseline HRSD score. Contrary to prediction, preference strength was negatively associated with symptom severity at 12 weeks ( β =1.90, p=.028) and had no effect at 24 weeks. Neither treatment congruence nor preference strength was related to 12- and 24-week remission (by Fisher's exact test and logistic regression, respectively).

Participants assigned to psychotherapy treatment achieved significantly lower 24-week HRSD scores (14.0±9.4) than those assigned medication (18.9±10.1) (F=4.12, df=1, p=.048). These treatment groups did not differ in 12-week HRSD scores or in 12- or 24-week remission rates.

Interaction terms of preference strength by age group, treatment type, and depression severity were not significant. Results did not change when available eight-week HRSD scores for two participants were substituted for missing 12-week scores. Finally, application of mixed-effects regression models as sensitivity analyses that accommodated all observed data across all assessment time points yielded results consistent with those reported above.

Other predictors of outcome

Regressions that controlled for baseline HRSD scores found degree of adherence (that is, proportion of pills taken or therapy sessions attended) to be unrelated to 12- or 24-week depression severity or remission.

A simultaneous regression of significant bivariate demographic and clinical predictors indicated that lower baseline HRSD ( β =.48, p=.010), being white ( β =4.32, p=.062), lower CANE scores ( β =.90, p=.007), and higher MMSE scores ( β =-1.61, p=.013) predicted lower 12-week HRSD scores (R 2 =.57, p<.001). In a separate regression, higher MMSE scores ( β =-2.24, p=.007) and higher functioning as measured by the WHODAS-II ( β =.44, p=.012) predicted lower 24-week HRSD scores (R 2 =.49, p<.001).

Discussion

The study's primary finding is that strength of a priori treatment preferences for either antidepressant medication or psychotherapy was associated with treatment initiation and adherence. Congruence of preference per se with assigned treatment was related to treatment initiation but not adherence, suggesting that a continuous measure of preference strength may be a more useful measure in clinical practice.

Neither congruence of treatment with patients' preference nor strength of preference was positively associated with depression severity or remission at 12 or 24 weeks. This finding is consistent with previous research ( 13 , 14 , 15 ) and suggests that the intensity of a patient's primary a priori treatment preferences is unrelated to clinical outcomes.

The findings also indicate that both nonsenior and senior participants had stronger preferences for, and expected a higher likelihood of improvement from, psychotherapy compared with antidepressant medication. Mean ratings of preference strength indicated that the average participant agreed to receive psychotherapy but had neutral or indifferent feelings about antidepressant medication. Indeed, only two participants randomly assigned to psychotherapy had neutral or negative preferences regarding it, and both nevertheless initiated treatment. In contrast, all eight participants who did not initiate treatment had been randomly assigned to receive antidepressant medication. Thus physicians should address, as needed, negative attitudes of patients toward antidepressants ( 26 ).

Our findings concerning stronger patient preferences for psychotherapy and the better 24-week outcomes achieved by those randomly assigned to this intervention compared with medication are especially noteworthy because primary care settings typically do not offer this treatment. Thus it is timely for administrators and clinicians to integrate psychotherapy into the primary care setting.

Our finding that strength of preference was positively associated with treatment initiation and adherence but that this association was not moderated by age group or depression severity suggests that preferences operate similarly across these spectrums. These findings should be interpreted cautiously, however, given the study's small sample and possible referral bias by primary care physicians.

The low depression remission rates achieved by participants at weeks 12 and 24 warrant analysis. They may have resulted from the treatment-resistant nature of the study cohort, which had moderate depression, had experienced recurrent depressive episodes, and had a history of previous treatment. Participants were also ethnically diverse, and many had several unmet social service needs. We suspect that participants receiving either antidepressant medication or interpersonal psychotherapy could have benefited from more aggressive treatment. For example, primary care physicians increased medication dosages for only some clinical nonresponders. This may partially explain the more severe depression experienced at 24 weeks by participants assigned to medication rather than to psychotherapy. The total sample's low remission rates also may have restricted the variability in depression outcomes needed to test hypotheses regarding the association of treatment preference strength with clinical outcomes.

Study limitations to be noted are that although all participants agreed to be randomly assigned to either medication or psychotherapy, 14 physician-referred patients (9%) refused to be screened for eligibility. Individuals with strong preferences regarding depression treatment may have refused the study, although their reasons for refusal are unknown. A further study limitation is our operational definition for treatment adherence—that is, proportion of psychotherapy sessions attended or pills taken. Although this definition placed each treatment on a relatively comparable scale, there are alternative metrics for scaling adherence. Furthermore, our analytic approach focused on a single dimension of treatment adherence. Thus, in addition to session attendance, psychotherapy participation involves engaging in an interactive process both in and out of the session—by completing homework assignments, for example. Pharmacotherapy similarly involves taking pills but also attending physician appointments where clinical status and side effects are monitored and managed.

Conclusions

Our randomization strategy, whereby participants were assigned treatment that was either congruent or incongruent with their primary stated preference, extends the small body of research investigating the value of meeting a patient's treatment preferences. Our results suggest that strength of such a priori preferences, more than preferences per se, is positively related to treatment initiation and adherence, albeit not to clinical outcomes. Thus primary care physicians can enhance the likelihood that patients with depression will initiate and complete treatment by inquiring about how strongly they prefer various treatments. Our findings suggest that when preferences lack intensity or are similarly intense, the most accessible treatment should be offered first. Alternatively, if a patient's treatment preference is particularly strong, that treatment option should be offered.

Conversely, assessment of treatment preferences might ideally be integrated into a process of education and treatment negotiation, which offers physicians an opportunity to educate patients about depression treatments. We suggest that future research focus on enhanced patient-clinician decision-making processes because they can potentially improve medical decisions ( 27 ) and are applicable to psychiatric disorders ( 28 , 29 ). These models involve a mutual process whereby the clinician elicits information from the patient about experiences and preferences, clarifies his or her values about different aspects of treatment, provides balanced information on all treatment options, and collaborates with the patient in formulating a treatment decision. Shared decision making may be particularly relevant for improving depressive outcomes because the approach seeks to enhance patients' autonomy and empower them in a manner that directly addresses depression-induced helplessness and hopelessness. Future research should also examine such relevant contingencies as cost of and access to treatment to determine the complex impact of preferences in real-life primary care settings.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant K23-MH069784 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by a grant from Forest Laboratories, Inc. The authors thank Andrew Leon, Ph.D., for advice on power calculations and statistical analyses.

Dr. Raue received support for this study from Forest Laboratories, Inc., in the form of drug support only. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55–61, 2001Google Scholar

2. Klap R, Unroe KT, Unützer J: Caring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:517–524, 2003Google Scholar

3. Schulberg H, Block M, Madonia M, et al: Treating major depression in primary care practice: eight-month clinical outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:913–919, 1996Google Scholar

4. Cooper-Patrick L, Gonzales J, Rost K, et al: Patient preferences for treatment of depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 28:382–383, 1998Google Scholar

5. Churchill R., Khaira M, Gretton V, et al: Treating depression in general practice: factors affecting patients' treatment preferences. British Journal of General Practice 50:905–906, 2000Google Scholar

6. Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne C, Liao D, et al: Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:527–534, 2000Google Scholar

7. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al: Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:2836–2845, 2002Google Scholar

8. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L: The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Archives of General Psychiatry 32:552–558, 1975Google Scholar

9. Eisenthal S, Emery R, Lazare A, et al: "Adherence" and the negotiated approach to patienthood. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:393–398, 1979Google Scholar

10. Brody D, Miller S, Lerman C, et al: Patient perception of involvement in medical care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 4:506–511, 1989Google Scholar

11. Cooper-Patrick L, Powe N, Jenckes M, et al: Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 12:431–438, 1997Google Scholar

12. Dwight-Johnson M, Unützer J, Sherbourne C, et al: Can quality improvement programs for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment? Medical Care 39:934–944, 2001Google Scholar

13. Bedi N, Chilvers C, Churchill R, et al: Assessing effectiveness of treatment of depression in primary care. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:312–318, 2000Google Scholar

14. Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, et al: Antidepressant drugs and generic counseling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomized trial with patient preference arms. British Medical Journal 322:1–5, 2001Google Scholar

15. Gum AM, Arean PA, Hunkeler E, et al: Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist 46:14–22, 2006Google Scholar

16. Ten Have T, Katz I, Coyne J: Overcoming the limitations or randomized clinical trials by incorporating preferences: the case of depression. Presented at National Institute of Mental Health Services Research Conference, Washington, DC, Apr 2, 2002Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 1995Google Scholar

18. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 23:56–62, 1960Google Scholar

19. Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P: Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12:189–198, 1975Google Scholar

20. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, et al: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984Google Scholar

21. Arean PA, Cook B: Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late life depression. Biological Psychiatry 52:293–303, 2002Google Scholar

22. von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K: A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 45:197–203, 1992Google Scholar

23. Epping-Jordan JA, Ustun TB: The WHODAS-II: leveling the playing field for all disorders. WHO Mental Health Bulletin 6:5–6, 2000Google Scholar

24. Reynolds T, Thornicroft G, Abas M, et al: Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE): development, validity, and reliability. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:444–452, 2000Google Scholar

25. SPSS, version 14.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc, 2005Google Scholar

26. Aikens JE, Nease DE Jr, Klinkman MS: Explaining patients' beliefs about the necessity and harmfulness of antidepressants. Annals of Family Medicine 6:23–29, 2008Google Scholar

27. O'Connor AM, Drake ER, Wells GA, et al: A survey of the decision-making needs of Canadians faced with complex health decisions. Health Expectations 6(2):97–109, 2003Google Scholar

28. Adams JR, Drake RE: Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Community Mental Health Journal 42:87–105, 2006Google Scholar

29. Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, et al: The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling 67:324–332, 2007Google Scholar