Initial Evaluation of the Peer-to-Peer Program

Peer-based interventions, which are based on the idea that those who have experienced mental illness can offer help and support to others, have become increasingly popular over the past decades ( 1 ). A recent estimate suggests that groups, programs, and organizations run by and for people with serious mental illness and their families outnumber professionally run mental health organizations by a ratio of almost 2 to 1 ( 2 ). Mutual assistance regarding mental illness is beginning to include more structured class-type programs alongside the array of support groups, peer counseling, and drop-in centers. Evaluations of more structured programs such as GROW, Inc. ( 3 ), and WRAP (Wellness Recovery Action Planning) ( 4 ) have indicated positive outcomes for participants, including improved psychological and social adjustment ( 5 ), increased security and self-esteem ( 6 ), and enhanced knowledge of early warning signs and coping skills ( 7 ).

Since 2000 the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) has offered Peer-to-Peer to mental health consumers nationally through its many affiliates ( www.nami.org/template.cfm?section=peer-to-peer ). Created by the second author, who has a psychiatric disability and is a former provider and manager in the mental health field, Peer-to-Peer is a free, structured, experiential, self-empowerment, relapse prevention, and wellness program for people with mental illnesses. It consists of nine two-hour sessions facilitated by trained mentors who are people with a mental illness. Currently available in 24 U.S. states, the program is highly valued by its graduates and popular enough to require waiting lists in many locations. However, it has never been systematically evaluated. Therefore, the primary purpose of this pilot study was to take a first step in evaluating Peer-to-Peer's effectiveness.

Methods

This first pilot evaluation employs a simple pre-post survey design. We did not have the resources to collect data outside the Peer-to-Peer class meetings or to send research staff to each locale. Therefore, we enlisted the help of Peer-to-Peer class mentors to voluntarily distribute and collect surveys at the beginning of the first class meeting and the end of the final class meeting. Because class time is at a premium, this method necessitated a very brief data-collection instrument.

We designed a 24-item voluntary, anonymous, paper-and-pencil survey based on focal points of the curriculum, the second author's extensive experience with Peer-to-Peer participants and mentors, and variables that would inform future more rigorous evaluation. The survey included 14 outcome items and nine questions about demographic characteristics. A final open-ended item, which was asked only at the end of the Peer-to-Peer program, addressed the experience of participating in the program: "Please describe any personal changes or insights you have experienced as a result of Peer-to-Peer." This item was designed to elicit spontaneous responses from participants that could help with data interpretation in this pilot study and inform the design of future outcome studies.

In addition to being given detailed administration directions, all mentors received postage-paid addressed envelopes in which to return all the survey forms to the researchers (both completed and blank forms were returned so as to not single out those not wishing to participate). Because the survey was anonymous, participants did not sign a consent form; instead, they were given a "disclosure form" that described the study and participation and provided our contact information. Individuals in 13 states took part in the survey. All study materials and procedures were approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board (IRB) before the study. Data were collected between July 2005 and April 2006.

Each participant's pre- and postintervention survey responses were matched via an IRB-approved anonymous identifier that participants self-generated by responding to certain items. Out of an estimated 550 possible study participants, 343 individuals (62%) completed preintervention surveys and 187 (34%) completed postintervention surveys. This yielded usable study data from 138 participants (those who completed surveys at both time points).

We could not collect data on attendees' reasons for declining to complete either or both surveys. However, there are two likely contributors to the relatively low response rate. First, we did not provide any compensation or incentive for participation. Second, Peer-to-Peer attendees who missed or were late for the first session or who missed or had to leave early from the last session had no alternative way to complete the survey.

Of the final sample of 138 participants, 81 (59%) were women. A total of 120 (87%) were white, eight (6%) were African American, and nine (7%) were from other racial or ethnic groups. Almost all (131 participants, or 95%) gave their sexual orientation as heterosexual; gay, lesbian, and bisexual people together constituted 5% of the sample (seven participants). The mean±SD age of participants was 43.0±12.8 (range 18 to 77).

Seven (5%) had less than a high school education, 21 (15%) had a high school degree, 37 (27%) had an undergraduate degree, 52 (38%) had attended some college, and 21 (15%) had attended graduate school. Thirty-five (25%) were working full-time, and 14 (10%) were working part-time. In addition, 64 (46%) reported volunteering somewhere regularly. Most (83 participants, or 60%) reported living in their own house or apartment (alone or with peers), 28 (20%) reported living with their parent or parents, 15 (11%) reported living in a supervised program, six (4%) were homeless, and six (4%) were in other residential arrangements.

Two-thirds (93 participants, or 67%) reported having one psychiatric diagnosis, 25 (18%) reported two diagnoses, and 21 (15%) reported three or more. Diagnoses were as follows, bipolar disorder, 68 participants (49%); depression, 42 (30%); schizophrenia, 18 (13%); and schizoaffective disorder, 18 (13%). Other diagnoses were reported at lower frequencies.

We had no way to determine whether our final sample is representative of all Peer-to-Peer participants. However, as one approximation, we compared the responses of people who completed only the first survey (N=217) and those who completed both surveys (N=138). All items were compared by using chi square tests, t tests, two-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. The two groups did not differ significantly (p<.05) on any demographic or outcome variable. A significant difference was found for only one item: those in the final sample were more likely to report volunteering regularly than those who returned only the first survey ( χ2 =3.96, df=1, p=.047).

Evaluation of pre-post changes on each outcome item used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p<.01 benchmark). This test is the nonparametric analog of the paired t test and was used because we had no prior information about the likely distribution of the data. Odds ratios from logistic regression were then used to evaluate demographic variations in the data. For example, we evaluated whether male participants were more likely than female participants to report a change on any of the outcome items. All analyses used SAS 9.1.

To summarize responses to the final open-ended item, the first author created a typed copy of all responses to this item and then read through them multiple times to categorize the responses. The rest of the team then discussed and checked these categorizations. The first author then chose certain responses as exemplars of each category to convey the meaning in respondents' own words.

Results

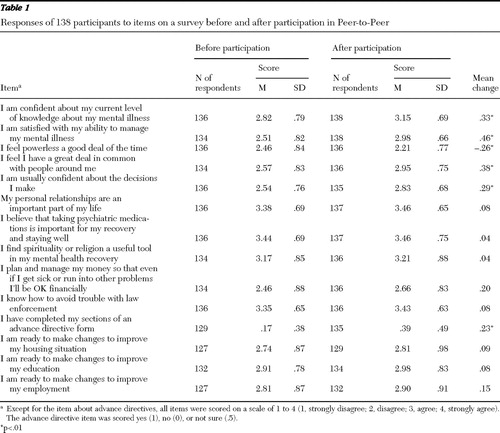

Table 1 presents response data for the outcome items from the survey. As indicated, participants showed significant positive gains on six of the 14 outcome items (p<.01). No significant changes were noted for the other eight items. None of the pre-post changes were in a negative direction (either significantly or not).

|

For demographic characteristics, only gender showed a significant association with any outcome variable. On the item "I am confident about my current level of knowledge about my mental illness," men were about a third as likely as women (odds ratio [OR]=.30, 95% confidence interval (CI) .14–.65; p<.01) to report an improvement. In addition, for three other items statistical trends by gender in the same direction were noted, with p values less than .05 but greater than .01. These items were "I plan and manage my money so that even if I get sick or run into other problems I'll be OK financially," "I have completed my sections of an advance directive form," and "I am ready to make changes to improve my education," The sample was too homogeneous to allow for analyses based on race-ethnicity.

People younger than 30 were significantly more likely than people 50 and older to report improvements on the item "I feel I have a great deal in common with people around me" (OR=4.38, CI=1.48–12.96; p=.008). However, no other significant associations were found for age. No significant associations were found between education or work status and outcome, and no diagnostic category was associated with more or less overall benefit from Peer-to-Peer participation.

Of the 138 participants, 127 (92%) responded to the open-ended final item on the survey. Their written comments about "personal changes or insights you have experienced as a result of Peer-to-Peer" were universally positive and readily clustered into five outcome-related categories. Below we describe each category and include a sample quotation.

The first category involved gaining information, tools, and skills from the curriculum. Participants commented on learning about mental illness, identifying triggers for and signs of relapse, acquiring information about medications, learning coping techniques and methods of stress management, and learning how to create an advance directive. One person wrote, "I feel whole again because of the contacts I made, the information I received, and the techniques for recovery I learned."

The second category involved appreciating the human connection with others and feeling less alone. Many participants commented on connecting with others who were taking the course and on the effect of hearing others' stories. This included receiving help and information from others with similar experiences, making new friends, creating a sense of belonging, having a safe place to talk about troubles, and finding comfort in knowing that other people experience mental illness. One participant wrote, "Although my mental illness is not like anyone else's, I am identical in some or a lot of feelings and actions. I have discovered that I am not alone in my illness."

The third category involved increased positive feelings about oneself as a result of taking the class. Participants also described increased self-esteem, strength as a person, self-confidence, and abilities to assert themselves. For example, "It has given me more self-confidence in facing my life."

The fourth category centered around feeling more motivated to take responsibility for one's own well-being. Participants commented that the course gave them a sense of empowerment where they previously felt powerless, instilled a sense of responsibility for their own relapse prevention planning, and increased their confidence about accepting their illness and working to stay well. One example of a response from this category is, "[I learned] that when I take responsibility for the results of living with mental illness I feel empowered. Then the focus becomes my mental health, instead of what's wrong with me."

Finally, the fifth category involved wanting to get more involved in advocacy as a result of taking the class. A number of people mentioned an increase in their confidence and willingness to educate others about mental illness. Some mentioned being inspired to help others and wanting to use their mental illness in a positive way through advocacy and education. One individual wrote, "I now have more self-esteem and confidence in my ability to engage in various activities regarding advocacy."

Discussion

This pilot study is the first evaluation of NAMI's Peer-to-Peer program. Because of resource constraints and the exploratory nature of the study, the methodology, sample, and instruments were modest. We intend to build on this initial study to conduct a more rigorous and larger Peer-to-Peer evaluation. Despite its limitations, the current pilot showed that Peer-to-Peer participants benefited in areas directly tied to the curriculum—specifically, knowledge and management of their illness, feelings of being less powerless and more confident, connection with others, and completion of an advance directive. The open-ended responses validated and amplified these results in that they clustered around the same themes.

The nonsignificant results for other survey items may have resulted from the pilot's methodological and measurement limitations. Participants' preintervention scores on several items were already high, leaving little room for improvement. Three other items used the wording "I am ready to make changes to improve my … [housing, education, or employment]." Several participants wrote in the margin that they answered no to these items because they liked their current housing, education, or employment situation and did not want to change it. This problem with the questions' wording will be corrected in future studies. Several other items changed in the expected direction but not to a significant degree. Whether the lack of significance was the result of an actual lack of effect, measurement issues, or insufficient power is something to be evaluated in future work. No item changed in a negative direction.

Conclusions

One purpose of any pilot evaluation is to assess whether the intervention can be feasibly evaluated. Peer-to-Peer clearly can be, and our next steps are to design and fund a more thorough and rigorous study that builds on the results and lessons of this pilot. We intend to create a stronger study using a pre-post design, likely with an additional three- or six-month follow-up to ascertain whether any gains are sustained. We will also interview participants outside the Peer-to-Peer class time, which will allow for longer data collection and therefore use of complete, standardized instruments, rather than single items, to address each construct or variable of interest.

In the meantime, persons interested in Peer-to-Peer specifically, or in structured consumer-led self-help classes more generally, can interpret these pilot results as indicating that the benefits Peer-to-Peer participants report anecdotally are supported by this study. Although additional research is needed before one can speak of "evidence" for the effectiveness of Peer-to-Peer, these initial results, coupled with the program's popularity among participants, suggest that it is a valuable potential resource for mental health consumers.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This pilot research was funded through a contract from NAMI's national office to the University of Maryland. NAMI's funding for Peer-to-Peer comes in part from an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Davidson L, Chinman M, Sells D, et al: Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:443–450, 2006Google Scholar

2. Goldstrom ID, Campbell J, Rogers JA: National estimates for mental health mutual support groups, self-help organizations, and consumer-operated services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 33:92–103, 2006Google Scholar

3. Rappaport J, Seidman E, Toro P, et al: Collaborative research with a mutual help organization. Social Policy 15:12–24, 1985Google Scholar

4. Copeland ME: Wellness Recovery Action Plan: a system for monitoring, reducing and eliminating uncomfortable or dangerous physical symptoms and emotional feelings, in Recovery and Wellness: Models of Hope and Empowerment for People With Mental Illness. Edited by Brown C. New York, Haworth, 2001Google Scholar

5. Roberts LJ, Salem D, Rappaport J, et al: Giving and receiving help: interpersonal transactions in mutual-help meetings and psychosocial adjustment of members. American Journal of Community Psychology 27:841–868, 1999Google Scholar

6. Kennedy EM: Community-based care for the mentally ill: simple justice. American Psychologist 45:1238–1240, 1990Google Scholar

7. Cook J: WRAP Evidence Base. Chandler, Ariz, Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery. Available at mentalhealthrecovery.com/art_selfmanagement.php Google Scholar