Treatment Patterns for Schizoaffective Disorder and Schizophrenia Among Medicaid Patients

Nosologic uncertainty surrounds the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder. Problems have been reported with its interrater reliability ( 1 , 2 ) and diagnostic stability ( 3 ). Further adding to the uncertainty, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder share with schizoaffective disorder specific clinical symptoms ( 4 ), structural brain abnormalities ( 5 , 6 ), and family history ( 7 ). Some researchers have even urged abolishing schizoaffective disorder as a diagnostic classification ( 8 ). In view of these concerns, we sought to compare the treatment patterns of patients diagnosed as having schizoaffective disorder with those of patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia to assess the extent to which these two patient groups receive different patterns of care.

Schizoaffective disorder, although relatively rare in the general population, is prevalent in mental health treatment settings ( 9 ). In the general population, schizoaffective disorder is roughly one-third ( 10 ) to one-sixth ( 11 ) as common as schizophrenia. Among heavy users of mental health services, however, the percentage of patients diagnosed as having schizoaffective disorder (24%) approaches that of schizophrenia (32%) ( 12 ). Within U.S. community hospitals, more patients are discharged with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder than schizophrenia ( 13 ).

Schizoaffective disorder is a heterogeneous clinical condition that encompasses psychotic, depressive, and manic symptoms. Despite its clinical severity and common occurrence in clinical practice, the pharmacologic treatment of schizoaffective disorder has received far less attention than that of schizophrenia or the major mood disorders ( 14 ). As a result, few well-defined clinical principles exist to guide the treatment of schizoaffective disorder.

Little is also known about the pharmacologic management that patients with schizoaffective disorder actually receive in community practice. Some evidence suggests that complex pharmacologic regimens are common. In one sample of consecutive inpatients treated for schizoaffective disorder (N=70), 90% of patients received antipsychotic medications and 79% received either mood stabilizers or antidepressant medications during their inpatient stay ( 15 ). Comparable data for outpatients are not available at present.

Clinical characteristics of patient samples with schizoaffective disorder vary with the treatment setting ( 16 ). In one long-term study of inpatients with persistent illness, for example, the outcomes of patients with schizoaffective disorder closely paralleled those of patients with schizophrenia ( 17 ). In another study of patients treated within a lithium clinic, there were few clinical differences between patients with schizoaffective disorder and those with bipolar disorder ( 18 ). One means of reducing sampling bias related to treatment setting and deriving a more representative characterization of schizoaffective disorder is through the assessment of patients within large and diverse systems of care.

The study presented here compared the demographic, pharmacologic, cotreated diagnostic, and service use characteristics of patients from Medicaid programs in two states who were treated for schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia. We estimated the relative treated prevalence of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia in two statewide Medicaid populations and characterized services received by each diagnostic group. Substantial differences in treatment patterns might help to illuminate the distinctive service needs of patients treated for either schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia.

Methods

Participant selection

Enrollment, service claims, and pharmacy data files from two state Medicaid programs (2002–2005) served as the data sources. In 2005 the total combined Medicaid enrollment of the two states was approximately 9.0 million. Two study groups were created: one with service claims for the treatment of schizoaffective disorder but not schizophrenia and one with claims for the treatment of schizophrenia but not schizoaffective disorder.

Patients treated for schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia were selected in several stages. Each selected patient had at least two claims with a primary diagnosis for either schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia during a six-month study period and no claims with primary diagnoses for the other disorder during a preceding six-month prestudy period. First, patients were selected if they had service claims with a primary diagnosis of either schizoaffective disorder ( ICD-9-CM code indicating DSM-IV diagnosis: 295.7) or schizophrenia (295.1–295.3, 295.6, 295.9) and at least six months of Medicaid eligibility before and after this index claim. Second, patients were selected if they had at least one additional service claim with a primary schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder diagnosis during their six-month study period. Third, patients were excluded if they had at least one primary diagnosis service claim for the other disorder (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) during the six-month study period or the six-month prestudy period. Fourth, because service and prescription claims are not available during inpatient treatment episodes, patients were excluded if they had been admitted for inpatient treatment for at least 30 inpatient days during the six-month prestudy period. Finally, patients who were younger than 18 years or older than 64 years were excluded.

Previous research indicates that patients with two outpatient claims for schizophrenia are likely to have schizophrenia ( 19 ). The treatment episode of each patient was defined to start on the date of the first of at least two schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia diagnosis claims to occur in a six-month period and to end six months after the first of these claims. A separate variable, episode status, partitioned patients into new or continuing cases by the presence of one or more claims for the same disorder (schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia) during the six-month period before the start of the treatment episode.

Among 77,849 patients who met the diagnostic criteria, 12,555 (16.1%) were excluded because they were not eligible for Medicaid for six consecutive months before and after the index claim, 2,694 (3.5%) were excluded because they had been admitted for at least 30 inpatient days during the six-month prestudy period, 7,011 (9.0%) were excluded because they were 65 years or older on the index date, and 2,685 (3.4%) were excluded because they were younger than 18 years on the index date. (Some persons were excluded for more than one reason.) This project was approved by the institutional review board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Patients were characterized with respect to demographic variables, including age, sex, and race or ethnicity (white, African American, Hispanic, and other). The two study groups were also characterized with respect to clinical, psychotropic medication, and service use variables.

On the basis of one or more service claims during the study period, patients were also dichotomously classified with respect to treatment of substance use disorder ( ICD-9-CM : 291, 292, and 303–305), anxiety disorder (300.0, 300.2, 300.3, and 308.3), depressive disorder (296.2, 296.3, 300.4, and 311), bipolar disorder (296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.9, and 301.13), and other mental disorders (290–319, except as noted above). (Service claims could be listed in any position on the claim—that is, as a first-listed diagnosis, as a second-listed diagnosis, etc.) These groups were not mutually exclusive.

Pharmacy claims during the study period were used to classify patients dichotomously with respect to antipsychotic medication, antidepressant, anxiolytic, and mood stabilizer treatment. Mood stabilizers included lithium preparations and antiepileptic medications prescribed in the absence of claims for a seizure disorder ( ICD-9-CM code 345). Among patients who were given a prescription for each of these medication classes, the mean medication possession ratio (MPR) was determined during the study period. MPR was defined as the number of days of medication dispensed as a percentage of the 180-day study period ( 20 ). Among patients given a prescription for antipsychotic medications, a dichotomous variable, antipsychotic MPR ≥.70 during the study period, was defined to represent at least moderate antipsychotic adherence ( 21 ).

Three dichotomous mental health service use variables during the study period were constructed to signify, respectively, hospital admissions and emergency department visits with primary mental disorders ( ICD-9-CM : 290–319) and psychotherapy visits (Current Procedural Terminology codes: 90804–90829, 90841–90847, 90849, 90853, 90855, 90857, 90875, and 90876). In addition, continuous variables were defined to measure the total number of visits for a primary mental disorder and primary general medical disorder (all other codes) during each study period. A comorbidity count was defined as the number of general medical disorders within the Charlson Comorbidity Index ( 22 ) for which patients received treatment during the study period (theoretical range of 0 to 17, with higher scores denoting greater medical comorbidity) ( 23 ).

Analytic strategy

The two study groups were compared with respect to demographic, clinical, pharmacologic treatment, and service use characteristics in chi square analyses to measure the strength of associations between each categorical independent variable and with t tests for continuous independent variables. Unadjusted risk ratios are also presented.

The PROC GENMOD in SAS version 9.13 was used to conduct a series of log linear regression models (binary outcomes) and Poisson regression models (continuous count data) with the demographic, clinical, pharmacologic treatment, and service use characteristics; episode status; state; and the study diagnostic group as independent variables. The binary outcomes included inpatient admission, psychiatric emergency department visit, psychotherapy use, and several pharmacotherapy treatments. The continuous outcomes included number of mental health and general medical visits, as well as number of treated general medical disorders within the Charlson Comorbidity Index during the study period.

We considered group differences with a two-tailed alpha <.01 to be statistically significant and those with a risk ratio of <1.10 or <.90 to be potentially substantial from a policy perspective.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

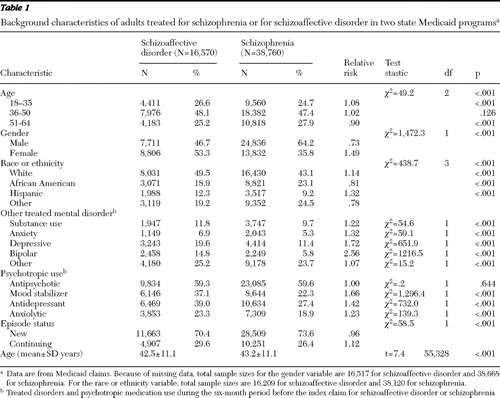

Approximately 29.9% (N=16,570) of the study sample received treatment for schizoaffective disorder, and the remaining 70.1% (N=38,760) received treatment for schizophrenia. Compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients with schizoaffective disorder had a significantly younger mean age, were more likely to be female, and were more likely to be white, Hispanic, or of other non-African-American race or ethnicity ( Table 1 ). In bivariate analyses, patients treated for schizoaffective disorder were also significantly more likely than their counterparts with schizophrenia to receive cotreatment of a substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and other mental disorder during the prestudy period, although the risk ratio for other mental disorders was not substantial ( Table 1 ). During this period, compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients with schizoaffective disorder were also significantly more likely to be treated with mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and anxiolytics. For both diagnostic groups, most treatment episodes were new, although patients with schizophrenia were proportionately more likely than those with schizoaffective disorder to have new treatment episodes.

|

Psychotropic medication use

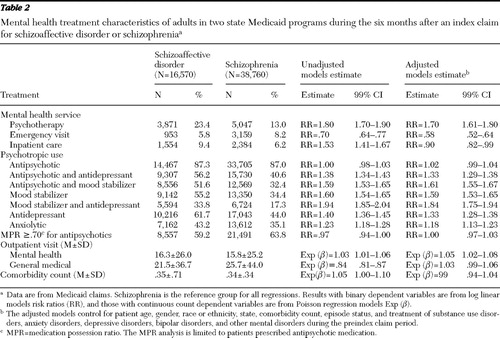

During the study period, a great majority of patients treated for schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia received antipsychotic medications ( Table 2 ). The proportion in each diagnostic group that was treated with antipsychotic medications did not significantly differ in the bivariate or multivariate analysis ( Table 2 ). Roughly one-half of patients treated for schizoaffective disorder with antipsychotic medications also filled prescriptions for antidepressants, and roughly one-half also received mood stabilizers during the study period. Compared with treatment for schizophrenia, treatment for schizoaffective disorder was significantly more strongly associated with antidepressant, mood stabilizer, and anxiolytic treatment in the bivariate and multivariate analyses ( Table 2 ). Even among patients without a bipolar diagnosis in the prestudy period, patients treated for schizoaffective disorder (N=7,316 of 14,112, or 51.8%) were significantly more likely than those treated for schizophrenia N=11,869 of 36,511, or 32.5%) to receive a mood stabilizer ( χ2 =1,616.6, df=1, p<.001). Similarly, among patients not treated for a depressive disorder during the prestudy period, patients with schizoaffective disorder (N=7,684 of 13,327, or 57.7%) were also more likely than those with schizophrenia (N=14,136 of 34,346, or 41.2%) to receive an antidepressant ( χ2 =1,053.1, df=1, p<.001) (data not shown).

|

Among patients treated with antipsychotic medications, a similar proportion of patients treated for schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia had an antipsychotic MPR of at least .70 ( Table 2 ).

Mental health service use

Patients treated for schizoaffective disorder were significantly more likely than those treated for schizophrenia to receive psychotherapy or to have an inpatient psychiatric admission ( Table 2 ). Although the association between schizoaffective disorder and psychotherapy remained significant after adjustment for background characteristics, the association with psychiatric admission reversed after adjustment for the background characteristics ( Table 2 ). In the model of inpatient psychiatric admission, several covariates were significantly related to hospital admission and had adjusted risk ratios greater than 1.40, including bipolar disorder, other mental disorders, state, and episode status (data not shown). Patients treated for schizophrenia were significantly more likely than those treated for schizoaffective disorder to receive mental health emergency department visits in the bivariate and multivariate analyses.

Compared with patients treated for schizophrenia, those treated for schizoaffective disorder received a slightly larger mean number of mental health visits during the study period ( Table 2 ).

General medical service use

A majority of patients treated for either schizoaffective disorder (N=12,308, or 74.3%) or schizophrenia (N=28,999, or 74.8%) did not receive treatment during the study period for any of the major medical disorders in the Charlson Comorbidity Index. In both groups, the most commonly treated major medical disorders were chronic pulmonary disease (N=2,116, or 12.8%, for patients with schizoaffective disorder and N=5,095, or 13.1%, for patients with schizophrenia). This was followed by diabetes mellitus without chronic complications (N=1,752, or 10.6%, and N=3,512, or 9.1%) (p<.001). Diabetes mellitus with chronic complications was also significantly more commonly treated among patients treated for schizoaffective disorder (N=168, or 1.0%) than for schizophrenia (N=274, or .7%) (p<.001). The mean medical comorbidity count did not significantly differ between patients diagnosed as having schizoaffective disorder or those diagnosed as having schizophrenia in either the bivariate or multivariate analysis ( Table 2 ). Patients treated for schizoaffective disorder, however, had a significantly lower mean number of general medical visits than did patients treated for schizophrenia, although a significant group difference was no longer evident after adjustment for background patient characteristics ( Table 2 ).

Discussion

Consistent with the results of clinical trials ( 24 ), our study findings showed that most outpatients with schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia received antipsychotic medications. In accord with a previous small inpatient study ( 15 ), most of the patients with schizoaffective disorder also received either mood stabilizers or antidepressant medications, although often in the absence of a mood disorder diagnosis.

There is a paucity of clinical trial data to guide the pharmacologic management of schizoaffective disorder. One review discouraged routine use of adjunctive antidepressants or mood stabilizers among patients with schizoaffective disorder without full major depressive or manic episodes, respectively ( 25 ). Because several second-generation antipsychotic medications are effective as monotherapy for manic and depressive symptoms in bipolar mania ( 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ), the mood-stabilizing properties of these medications may be helpful in schizoaffective disorder. The unadjusted findings presented here suggest that compared with outpatients with schizophrenia, those with schizoaffective disorder who are treated with antipsychotic medications are approximately 38% more likely to receive antidepressants and 60% more likely to receive mood stabilizers. At a mental health care system level, medication management differences of this magnitude may have significant financial implications and may come under increasingly close scrutiny from payers given continuing overall growth in spending on psychotropic medications ( 30 ).

Antipsychotic medication nonadherence and partial adherence are important sources of morbidity in schizophrenia ( 31 ). The study presented here suggests that widespread problems with antipsychotic medication adherence also exist for schizoaffective disorder. Among patients receiving antipsychotic medications, those with schizoaffective disorder were as likely as those with schizophrenia to have antipsychotic MPRs below levels associated with increased risks of psychiatric hospitalization ( 20 , 32 ) and increased mental health care costs ( 33 ).

Patients treated for schizoaffective disorder and those treated for schizophrenia place different demands on the health care system. In keeping with previous research ( 34 ), our study found that outpatients treated for schizoaffective disorder were significantly more likely than outpatients treated for schizophrenia to be admitted for inpatient psychiatric care. However, after the analysis controlled for the higher level of cotreated disorders and other covariates, patients treated for schizoaffective disorder were significantly less likely than their counterparts with schizophrenia to receive inpatient psychiatric treatment.

Patients with schizoaffective disorder were significantly more likely than patients with schizophrenia to receive psychotherapy. Clinical trials with mixed populations of patients with schizophrenia and those with schizoaffective disorder have demonstrated that a variety of intensive psychotherapies and psychosocial interventions significantly improve symptom, social, and vocational outcomes ( 35 , 36 , 37 ). The extent to which community-based psychotherapies for patients with psychotic disorders incorporate evidence-based techniques remains largely unknown ( 38 , 39 ).

Consistent with community epidemiological studies ( 10 , 11 ), our study found that most patients treated for schizoaffective disorder were female. In community and clinical samples, females account for a majority of patients with bipolar disorder ( 40 , 41 ) and major depression ( 42 , 43 ). The affective dimension of schizoaffective disorder may contribute to its observed gender distribution. Despite this gender distribution, patients with schizoaffective disorder were more likely than those with schizophrenia to receive treatment for a substance use disorder ( 44 ).

An important strength of the study presented here is that it is based on large, ethnically and geographically diverse clinical populations. The study also has several limitations. Perhaps most important, the diagnostic classifications are based entirely on clinical diagnoses that are not subject to expert diagnostic validation. Problems with the diagnostic consistency of schizoaffective disorder are well known ( 1 , 3 ). The results portray service use among patients treated for schizoaffective disorder and those treated for schizophrenia rather than among patients who meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for each disorder.

Detection bias might contribute to the association between psychotherapy and schizoaffective disorder, because provision of psychotherapy offers opportunities for clinicians to detect mood symptoms required for a schizoaffective disorder diagnosis. In addition, use of several classes of psychotropic medications may prompt some physicians to label some patients with schizoaffective disorder. Second, Medicaid data provide little information concerning why patients receive various services and no information concerning several factors, such as treatment effectiveness, patient treatment preferences, stressful life events, and family support, that likely influence the pattern of mental health service use. Third, to help ensure complete service use retrieval, patients with extensive inpatient treatment during the prestudy period were excluded. This exclusion limits the generalizability of the findings. Fourth, the study period was limited to 180 days; other service use patterns might have emerged over a longer period of observation. Fifth, multiple comparisons increase the likelihood of type I error. Finally, the results may not be safely extended to the large number of patients treated for schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia who are not covered by the Medicaid program.

Conclusions

Psychiatrists have long struggled with the management of patients who present with a combination of psychotic and mood symptoms ( 5 ), and questions persist concerning the wisdom of distinguishing schizoaffective disorder from schizophrenia. Compared with patients treated for schizophrenia, patients treated for schizoaffective disorder place distinctive stresses on the health care system. Specifically, compared with patients with schizophrenia, those with schizoaffective disorder utilize a broader range of classes of psychotropic medications and are more likely to receive psychotherapy and inpatient psychiatric care, although they are less likely to use emergency psychiatric services. These distinctive health care service patterns may reflect differences in the symptom patterns that characterize schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia. Alternatively, clinical labeling of patients with a schizoaffective diagnosis, which some ( 45 , 46 ) but not all ( 47 , 48 ) research suggests has a better outcome than schizophrenia, might increase the likelihood of referral for psychotherapy or prescription of adjuvant treatments. Determining the extent to which clinical symptoms and diagnostic labeling contribute to prevailing service patterns will require longitudinal practice-based research studies with well-characterized patients.

The findings provide clues as to how mental health care policies may affect the care of patients with schizoaffective disorder. The complex pharmacological regimens that characterize treatment of schizoaffective disorder underscore the extent to which these patients may be even more affected than patients with schizophrenia by medication cost-sharing arrangements ( 49 ), medication prior authorization programs ( 50 ), and other policies aimed at stemming expenditures for psychotropic medications. The results also provide a rationale for distinguishing these two disorders in methods used to generate report cards comparing plans or health care professionals on treatment patterns and expenditures ( 51 ). Finally, because poor medication adherence is as common in schizoaffective disorder as in schizophrenia, many patients with schizoaffective disorder may benefit from programs aimed at improving medication adherence in community settings ( 52 ).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs.

Dr. Olfson has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, AstraZeneca, and Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. Dr. Olfson has also worked as a consultant for Pfizer, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Marcus has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, AstraZeneca, and Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. Dr. Wan is an employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

1. Maj M, Pirozzi R, Formicola AM, et al: Reliability and validity of the DSM-IV diagnostic category of schizoaffective disorder: preliminary data. Journal of Affective Disorders 57:95–98, 2000Google Scholar

2. Faraone SV, Blehar M, Pepple J, et al: Diagnostic accuracy and confusability analyses: an application to the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies. Psychological Medicine 26:401–410, 1996Google Scholar

3. Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, et al: Congruence of diagnoses 2 years after a first-admission diagnosis of psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:593–600, 2000Google Scholar

4. Adler CM, Strakowski SM: Boundaries of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 26:1–23, 2003Google Scholar

5. Kempf L, Hussain N, Potash JB: Mood disorder with psychotic features, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia with mood features: trouble at the borders. International Review of Psychiatry 17:9–19, 2005Google Scholar

6. Getz GE, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, et al: Neuroanatomic characterization of schizoaffective disorder using MRI: a pilot study. Schizophrenia Research 55:55–59, 2002Google Scholar

7. Laursen TM, Labouriau R, Licht RW, et al: Family history of psychiatric illness as a risk factor for schizoaffective disorder: a Danish register-based cohort study. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:841–848, 2005Google Scholar

8. Lake CR, Hurwitz N: Schizoaffective disorders are psychotic mood disorders: there are no schizoaffective disorders. Psychiatry Research 143:255–287, 2006Google Scholar

9. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al: Pharmacologic treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Psychopharmacology 114:529–538, 1994Google Scholar

10. Scully PJ, Owens JM, Kinsella A, et al: Schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar disorder within an epidemiologically complete, homogeneous population in rural Ireland: small area variation in rate. Schizophrenia Research 67:143–155, 2004Google Scholar

11. Widerlöv B, Lindström E, von Knorring L: One-year prevalence of long-term functional psychosis in three different areas of Uppsala. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 96:452–458, 1997Google Scholar

12. Kent S, Fogarty M, Yellowlees P: Heavy utilization of inpatient and outpatient services in a public mental health service. Psychiatric Services 46:1254–1257, 1995Google Scholar

13. Kozak LJ, DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ: National hospital discharge survey: 2004 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Statistics 13:1–209, 2006Google Scholar

14. McElroy SL, Keck PE, Strakowski SM: An overview of the treatment of schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 5):16–22, 1999Google Scholar

15. Flynn J, Grieger TA, Benedek DM: Pharmacologic treatment of hospitalized patients with schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatric Services 53:94–96, 2002Google Scholar

16. Baethge C: Long-term treatment of schizoaffective disorder: review and recommendations. Pharmacopsychiatry 36:45–56, 2003Google Scholar

17. Williams PV, McGlashan TH: Schizoaffective psychosis: I. comparative long-term outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:130–137, 1987Google Scholar

18. Rosenthal NE, Rosenthal LN, Stallone F, et al: Toward the validation of RDC schizoaffective syndromes. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy Research 5:205–211, 1985Google Scholar

19. Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al: Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:69–71, 1992Google Scholar

20. Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al: Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Medical Care 40:630–639, 2002Google Scholar

21. Ward A, Ishak K, Proskoroversusky I, et al: Compliance with refilling prescriptions for atypical antipsychotic agents and its association with the risks for hospitalization, suicide, and death in patients with schizophrenia in Quebec and Saskatchewan: a retrospective database study. Clinical Therapeutics 28:1912–1921, 2006Google Scholar

22. Charlson ME, Pomei P, Ales KL, et al: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases 40:373–383, 1987Google Scholar

23. Deyo RA, Cherkin D, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 45:613–619, 1992Google Scholar

24. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Association, 2004. Available at www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=5217 Google Scholar

25. Levinson DF, Umapathy C, Mushtaq M: Treatment of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia with mood symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1138–1148, 1999Google Scholar

26. Perlis RH, Welge JA, Bornik LA, et al: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:509–516, 2006Google Scholar

27. Bowden CL, Grunze H, Mullen J, et al: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study of quetiapine or lithium as monotherapy for mania in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:111–121, 2005Google Scholar

28. Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE Jr, Kramer M, et al: Rapid antimanic effect of risperidone monotherapy: a 3-week multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1057–1065, 2004Google Scholar

29. Keck PE, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, et al: A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1651–1658, 2003Google Scholar

30. Frank RG, Conti RM, Goldman HH: Mental health policy and psychotropic drugs. Milbank Quarterly 83:271–298, 2005Google Scholar

31. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637–651, 1997Google Scholar

32. Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al: Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 55:886–891, 2004Google Scholar

33. Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al: Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:692–699, 2004Google Scholar

34. Thompson EE, Neighbors HW, Munday C, et al: Length of stay, referral to aftercare, and rehospitalization among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 54:1271–1276, 2003Google Scholar

35. Huxley NA, Rendall M, Sederer L: Psychosocial treatments in schizophrenia: a review of the past 20 years. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:187–201, 2000Google Scholar

36. Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, et al: Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:866–876, 2004Google Scholar

37. Andres K, Pfammatter M, Garst F, et al: Effects of a coping-orientated group therapy for schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients: a pilot study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 101:318–322, 2000Google Scholar

38. Latimer EA, Bush PW, Becker DR, et al: The cost of high-fidelity supported employment programs for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:401–406, 2004Google Scholar

39. Fiander M, Burns T, McHugo GJ, et al: Assertive community treatment across the Atlantic: comparison of model fidelity in the UK and USA. British Journal of Psychiatry 182:248–254, 2003Google Scholar

40. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:543–552, 2007Google Scholar

41. Moreno C, Laje G, Blanco C, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of bipolar disorder in youth. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:1032–1039, 2007Google Scholar

42. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, et al: Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey: I. lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders 29:85–96, 1993Google Scholar

43. Pingitore D, Snowden L, Sansone RA, et al: Persons with depressive symptoms and the treatments they receive: a comparison of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. International Journal of Psychiatry Medicine 31:41–60, 2001Google Scholar

44. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Rosenberg SD, et al: Substance use disorder in hospitalized severely mentally ill psychiatric patients: prevalence, correlates, and subgroups. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:179–192, 2000Google Scholar

45. Grossman LS, Harrow M, Goldberg JF, et al: Outcome of schizoaffective disorder at two long-term follow-ups: comparisons with outcome of schizophrenia and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:1359–1365, 1991Google Scholar

46. Jäger M, Bottlender R, Strauss A, et al: Fifteen-year follow-up of ICD-10 schizoaffective disorders compared with schizophrenia and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109:30–37, 2004Google Scholar

47. Tsuang D, Coryell W: An 8-year follow-up of patients with DSM-III-R psychotic depression, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1182–1188, 1993Google Scholar

48. Sim K, Chan YH, Chong SA, et al: A 24-month prospective outcome study of first-episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder within an early psychosis intervention program. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68:1368–1376, 2007Google Scholar

49. Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley JA, et al: Adverse events associated with prescription drug cost-sharing among poor and elderly persons. JAMA 285:421–429, 2001Google Scholar

50. Law MR, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB: Effect of prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotic agents on pharmacy utilization and reimbursements. Psychiatric Services 59:540–546, 2008Google Scholar

51. Hermann RC, Rollins CK, Chan JA: Risk-adjusting outcomes of mental health and substance-related care: a review of the literature. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 15:52–69, 2007Google Scholar

52. Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al: Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1653–1664, 2002Google Scholar