Characteristics of Inpatients With a History of Recurrent Psychiatric Hospitalizations: A Matched-Control Study

Recurrent admission to the psychiatric hospital has often been viewed as not only avoidable and excessively expensive but also as undesirable for the care of patients as well as for the system of care ( 1 ). Literature reviews ( 1 , 2 ) have emphasized that the most consistently identified predictor of readmission has been the number of previous hospitalizations ( 1 ). Psychosis has been the syndrome most frequently associated with recurrently admitted patients ( 1 ). Behaviors of noncompliance with prescribed medications and treatment dropout have also been frequently noted ( 3 , 4 ). The definitions of recurrent admission have clustered between more than one within 12 months to more than two within 18 months ( 2 ).

This chart review study examined patients with a history of being recurrently admitted to a psychiatric inpatient service who were matched with a comparison group of patients without such a history. Our goal was to better understand the characteristics of recurrently admitted patients in our effort to fashion an approach that will be effective in reducing admissions and improving the lives of our patients.

Methods

The psychiatric hospital in this study is the principal inpatient setting for a large public mental health system serving a population area of about 845,000. Patients were admitted on the basis of clinical need without regard to payer status. Clinical need for both voluntary and involuntary admissions almost always meant being dangerously unable to care for oneself or severe agitation and poor impulse control. Patients with substance use disorders and no co-occurring axis I mental health disorders were usually not admitted unless they had an axis II disorder that was dangerously out of control. There was a strong tendency for patients to return to the site of previous hospitalizations. Roughly the same proportion of our patients from both the control and recurring admission groups had documented prior admissions (based on chart review data) to other hospitals in the area during the time of the survey. However, the data were not consistently or accurately enough noted in the medical record to include in the analysis for this study. All patients were at equal risk to be jailed or housed in alternative settings (such as nursing homes, step-down units, and diversion programs), and it was rare for a patient to be denied nonhospital services within our system for prior behavior unless his or her present behavior justified such a decision. Because of the availability of crisis programs and alternatives to hospitalization, it was unusual to have hospitalization function as a part of an integrated treatment plan unless alternative and crisis diversion programs had failed or were too risky.

With complete institutional review board review and approval, we examined the medical records of 75 consecutively admitted inpatients (September 2005 through July 2006) who were 18 years or older and who had had at least two psychiatric hospitalizations during the 18 months before the index admission (that is, history of recurrent psychiatric hospitalization). We employed a matched-pair design with the comparison group, which was composed of patients matched to the recurrently admitted group by the next admitted adult (18 years or older) who had either one or no admissions in the prior 18 months. We chose three or more admissions within 18 months (two before the index admission plus the index admission) as a measure of an intense phenomenon over a long enough period to consider it enduring (18 months). Admission data were available for all patients for 24 months before and 24 months after the index admission.

Data were extracted from the medical records. We chose variables based on reviews of the literature ( 1 , 2 ). Statistical analyses included exploratory univariate comparisons of demographic and clinical characteristics at the time of index hospitalization for the two groups by using chi square analysis, t tests, and Wilcoxon rank tests, as appropriate. Because the dependent variable of interest was number of hospitalizations, variables that were significantly different in univariate analyses (p<.05, two-tailed) along this measure were then entered into separate, exploratory multiple linear regression analyses to identify patient characteristics that were associated with the number of hospitalizations during the full 48 months and the number of readmissions in the 24 months after the index hospitalization. A backward stepwise method was used to identify patient variables independently associated with number of inpatient admissions.

Results

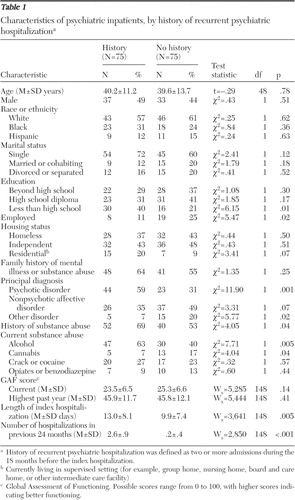

As noted in Table 1 , significant differences between recurrently admitted inpatients and inpatients in the matched-control group were observed in educational achievement, employment status, principal diagnosis, past and current substance abuse, and length of index hospitalization.

|

Results of the stepwise multiple regression showed that only two patient characteristics, diagnosis and unemployment status (based on a yes or no response to a structured evaluation question in the medical record), were independently associated with more hospitalizations over the entire 48 months (F=8.21, df=4 and 145, p=.001). Patients diagnosed as having a psychotic disorder had significantly more inpatient admissions than those with "other disorders" ( β =2.26, SE=.75, t=3.17, df=131, p=.003) or affective disorders ( β =1.85, SE=.52, t=3.52, df=131, p=.001). Psychotic disorders accounted for 10.6% of the variance in inpatient utilization. Unemployed patients also had significantly more hospitalizations during the 48-month period than those who were employed ( β =1.46, SE=.61, t=2.38, df=131, p=.02). Unemployment status contributed 5.0% unique variance to the model.

Additional analyses suggested that unemployment was not a proxy of psychosis or severity of illness because employment status did not differ across the three diagnostic groups. Furthermore, no significant differences according to employment status were observed in current Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores or in highest GAF scores in the past year. Also, a diagnosis of psychotic disorder was not associated with significant differences in current GAF scores or in highest GAF scores.

A second regression analysis was conducted with the number of readmissions in the 24 months after index hospitalization as the dependent variable. The only significant variable that emerged (F=16.36, df=2 and147, p=.001) was the number of admissions before the index hospitalization ( β =.42, SE=.08, t=5.14, df=131, p=.001, 16% of variance). A nonsignificant statistical trend was observed for patients with affective disorders, who had fewer readmissions than patients with psychotic disorders ( β =–.52, SE=.28, t=–1.86. df=131, p=.06).

Discussion and conclusions

Consistent with previous reports ( 1 ), our unadjusted univariate analyses revealed a number of differences in clinical and demographic characteristics that suggested that patients with a history of being recurrently admitted were more likely than those in the control group to have instances of psychotic disorders, substance abuse, and lack of education. However, regression analyses revealed that only two patient variables, psychosis and unemployment, were independently associated with the total number of hospitalizations over 48 months; these variables accounted for 11% and 5%, respectively, of the variance in readmission. Additional analyses confirmed that psychosis was not associated with either employment or GAF scores and that neither employment nor diagnosis independently predicted subsequent hospitalization after the index period. Our findings confirm those of others that associate psychosis and unemployment with recurrent admission ( 1 , 5 , 6 ) and raise the possibility that the association of psychosis and unemployment are not proxies for one another but rather contribute independently to recurrent admission status. Employment, therefore, may serve a protective function for readmission ( 6 ).

We found no association between unemployment and psychosis within the total sample; however, we cannot say whether either was or was not a proxy for unmeasured characteristics potentially related to functional outcomes. It is possible that employment status was a correlate of a general ability, such as neurocognition, social skills ( 7 ), or insight ( 8 ), that is required for effective illness self-management as well as employment ( 4 ). Furthermore, attitudes of alienation and mistrust, which are deleterious for collaborative involvement in patient care for any chronic illness, may be uniquely related to some but not all expressions of psychosis.

We recognize weaknesses of the study, namely that the diagnostic categories used do not capture the considerable heterogeneity of individuals within each group and that GAF scores are a limited measure of overall functioning ( 9 ). We also acknowledge the weakness of not being able to assess accurately the out-of-network hospitalization experience or to be certain that other events, such as jail and moving in and out of the community, could have acted in a nonrandom fashion to skew the findings. However, although there is no suggestion that these issues were operant in this sample, we acknowledge that generalization of our findings to other groups is uncertain.

Our design of comparing patient characteristics of those with a history of recurrent admission and those without such a history over four years (24 months before and 24 months after the index hospitalization) is unique. Our data contribute to the perspective that, independent of severity of illness, participation in a structured, meaningful social activity (such as work) may protect individuals from recurrent psychiatric hospitalization.

More research is needed in order to clarify the relationship between employment or some other meaningful social activity and recurrent hospitalization. Meanwhile, emphasizing employment in the treatment and rehabilitation of those who are repeatedly admitted to psychiatric hospitalization should be strongly considered. We have implemented a program in which patients in recovery who are unconnected with the identified patient's health care providers (but are intensely supervised by other mental health practitioners) work as mentors or guides for patients who have been recently discharged and have a history of recurrent admission. The mentor meets with the patient on a regular basis and helps the patient make his or her way through the challenge of living outside the hospital by providing inspiration, support, and practical advice and assistance, which includes, in some instances, helping with the decision to seek employment opportunities. Our experience will be presented in subsequent reports, but we can say that the program is both feasible and promising.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding was provided through a grant from Eli Lilly and Company and the George D. and Ester S. Gross Professorship, both of which were to Dr. Sledge.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Klinkenberg WD, Calsyn RJ: Predictors of receipt of aftercare and recidivism among persons with severe mental illness: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:487–496, 1996Google Scholar

2. Sledge WH, Dunn C: Recurrently readmitted inpatient psychiatric patients: characteristics and care; in Principles of Inpatient Psychiatry. Edited by Ovsiew F, Munich R. Baltimore, Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, 2008Google Scholar

3. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856–861, 1995Google Scholar

4. Prince JD: Therapeutic alliance, illness awareness, and number of hospitalizations for schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 195:170–174, 2007Google Scholar

5. Burns T, Catty J, White S, et al: The impact of supported employment and working on clinical and social functioning: results of an international study of individual placement and support. Schizophrenia Bulletin 35:949–958, 2009Google Scholar

6. Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, et al: Day treatment versus supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: a replication study. Psychiatric Services 47:1125–1127, 1996Google Scholar

7. Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Zarate R: Recent advances in social skills training for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32(suppl 1):S12–S23, 2006Google Scholar

8. Lincoln TM, Lullmann E, Rief W: Correlates and long-term consequences of poor insight in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophrenia Bulletin 33:1324–1342, 2007Google Scholar

9. Clements KM, Murphy JM, Eisen SV, et al: Comparison of self-report and clinician-rated measures of psychiatric symptoms and functioning in predicting 1-year hospital readmission. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 33:568–577, 2006Google Scholar