Costs Associated With Changes in Antidepressant Treatment in a Managed Care Population With Major Depressive Disorder

Depression is a highly prevalent disorder, affecting approximately 35 million adults in the United States each year ( 1 ). Complications of depression, such as fatigue, lack of interest, and difficulty with memory and concentration, have a negative impact on the social interactions and work functioning of depressed patients. Workers with depression were found to have more total health-related lost productive time than those without depression, mainly because of reduced performance at work ( 2 ). In addition to reduced productivity, depression is also associated with work absence: according to the National Comorbidity Survey, 59% of U.S. adults with a lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder were unable to work an average of 35 days in the prior year ( 1 ).

Reduced productivity and absenteeism contribute to indirect costs of disease, and studies have shown that both of these issues factor into the costs of depression ( 2 , 3 ). One claims database analysis of a single company found that each depressed woman cost her employer $9,265 in 1998, compared with $8,502 for depressed men in the same year ( 3 ). Work absence costs contributed significantly to the excess costs for women. In addition, employees with depression classified as likely to be resistant to treatment were found to incur greater medical and work loss costs, compared with patients whose depression was not treatment resistant ( 4 ). Effective management of depression has the potential to positively influence an individual's work performance and attendance, and it is crucial not only to patients but also to employers who shoulder a substantial portion of the indirect costs of the disease.

Pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and combinations of treatments are recommended for acute and sustained management of depression ( 5 ). Antidepressant medication is a primary treatment choice for clinical depression, but psychotherapeutic approaches such as cognitive-behavioral therapy are also effective and may be implemented alone or to complement pharmacological treatment. Commonly used classes of antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Despite these options, only 50% to 60% of patients respond to the first antidepressant prescribed ( 6 ). One trial reported that only 34% to 37% of patients randomly assigned to initial treatment with an SSRI, the most commonly prescribed antidepressant, continued to use it for nine months with acceptable effectiveness ( 7 ).

Treatment guidelines for patients who do not respond fully to the first line of treatment suggest increasing the dose of the antidepressant, switching to another antidepressant of the same or a different class, or augmenting the antidepressant by adding a second drug ( 5 , 8 ). Similarly, switching medication or modifying the medication dose or the administration routine are strategies for addressing any problematic side effects ( 5 ). The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial was designed to compare various treatment strategies among patients with major depressive disorder who did not respond satisfactorily to first-line treatment with an SSRI ( 9 ). Switching to another antidepressant was associated with symptom remission for approximately one-fourth of patients ( 10 ), and augmentation with sustained-release bupropion or buspirone was associated with remission for approximately one-third of patients ( 11 ).

Previous research has shown that depression is associated with substantial direct and indirect costs ( 2 , 3 , 4 ). This study was designed to expand these findings by investigating whether health care costs, productivity losses, and disability claims differ between patients with depression who maintain their index antidepressant and those who use stepwise treatment—that is, switching or augmenting pharmacotherapy.

Methods

Study objectives

The data for the study were obtained from an administrative claims database of a large U.S. health plan affiliated with i3 Innovus. The database contained disability information derived from multiple employers. We addressed the following four objectives. First, we estimated the number of individuals with major depression in the plan. Second, we described antidepressant treatment patterns of three cohorts (that is, switching, augmenting, or maintaining the index prescription) and detailed the burden of comorbidity among the cohorts. Third, we calculated the number and costs of depression-related and all-cause medical visits in the cohorts. Finally, we calculated productivity losses (measured as days absent from the workplace) and costs for disability claims in the cohorts.

Study design

Data were gathered from July 1, 2002, through June 30, 2006. In order to be included in this study, participants were required to meet the following criteria. First, participants had to have filled a prescription for an antidepressant—SSRI, SNRI, NDRI, MAOI, TCA, or other (that is, bupropion mirtazapine, nefazodone, or trazodone)—anytime between January 1, 2003, and June 30, 2005. In this study, the first fill date in this period was defined as the index date. Second, participants had to have at least one outpatient-based medical claim with a diagnosis of depression corresponding to ICD-9 codes 296.2x or 296.3x at any point between 180 days before and 365 days after the index date. Third, participants had to be continuously enrolled in a medical and pharmacy benefits plan for at least 180 days before and 365 days after the index date. Fourth, participants were required to be between 18 and 64 years of age at the year of the index prescription. Finally, all participants had to be antidepressant treatment naïve, which was defined as no claim for an antidepressant prescription at least 180 days before the index date. We subsequently eliminated individuals taking a combination of antidepressants simultaneously on the index date and those with missing information on gender. An institutional review board waiver was received because this study used deidentified administrative claims data.

Study cohorts

The sample was divided into three cohorts: switchers, augmenters, and maintainers. The first two cohorts either switched or augmented their index therapy with any of the following nonindex antidepressant medications: SSRI, SNRI, NDRI, MAOI, TCA, or other (bupropion mirtazapine, nefazodone, or trazodone). Therapy switch was defined as the fill of a nonindex antidepressant medication with no subsequent fill of the index medication. Therapy augmentation was defined as the addition of a new study medication to therapy with continued filling (at least one additional fill) of the index medication. Maintainers were defined as participants who did not switch or augment their therapy. However, they may have discontinued therapy at some point during the study period.

Study measures

To assess health care costs and utilization, we calculated the number and cost of depression-related and all-cause ambulatory visits and inpatient visits in the 180 days before the index date (preindex period) and in the 365 days after the index date (postindex period), as well as total overall costs during these two periods. Health care costs were computed as a function of patient and health plan paid amounts. Costs were computed for ambulatory services, inpatient services, and pharmacy dispensing, and total combined costs were calculated. Utilization and costs were considered to be related to depression if participants had a depression diagnosis corresponding to the aforementioned ICD-9 codes in any position on a medical claim or a fill for an antidepressant. One visit per provider type per service date was permitted. Utilization was further categorized as either ambulatory visits (that is, the number of depression-related and all-cause visits to an outpatient facility or office setting) or inpatient visits (that is, the number of hospital admissions for depression or for all causes).

Comorbid conditions in the preindex period were identified using the clinical classification software maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality ( 12 ). Psychiatric conditions (for example, anxiety, ICD-9 code 300.02) were presented separately from other chronic and acute comorbid conditions. The use of other psychiatric medications was determined in the preindex period and in the postindex period. Paid amounts for psychiatric medications were calculated as well. In the analyses, we identified the major classes of psychiatric medications (anxiolytics, hypnotics, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medications, and mood stabilizers). The average copayment amount for antidepressant prescription fills was calculated during the postindex period.

We defined adherence to pharmacotherapy (taking into account all antidepressant therapies during the postindex period) in terms of medication possession ratio (MPR), with the number of days of available therapy in the numerator and the total days in the postindex period in the denominator (that is, 365 days).

The number of days lost as a result of health care visits for depression was calculated using one-half day for each outpatient visit and one day for each day of inpatient stay. The costs associated with the number of days lost were calculated using the average wage for each census region as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the relevant time period. Finally, we also used the total business days lost and wage replacement costs reported on disability claims.

Statistical methods

We used t tests, Scheffé's tests, and Wilcoxon tests to compare across study cohorts unadjusted means of patient demographic characteristics (gender, age, region, payer or plan [for example, health maintenance organization, point of service, or preferred provider organization], and insurance type [commercial versus Medicaid]). Generalized linear modeling (GLM) was performed to determine differences in health care costs in the three treatment-pattern cohorts after controlling for necessary baseline characteristics and covariates. This choice of modeling accounts for nonconstant variance and maintains the original scale of the data, thus eliminating the need to transform cost data to achieve homoscedasticity and the need to retransform using a Duan smearing estimator for interpreting results ( 13 ). The functional form and distribution of costs was investigated using the Manning ( 14 ) and Mullahy ( 15 ) method (that is, modified Park test to determine the appropriate model to use for health care expenditures). The gamma distribution with a log-link function was used to estimate positive costs. Robust standard errors were calculated using the Huber-White correction for the variance-covariance matrix of the parameter estimates. Finally, after control for all necessary covariates, logistic models were used to determine the adjusted likelihood of switching or augmenting therapy.

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics and preindex variables for each of the three cohorts. A total of 7,273 participants met the criteria for inclusion. Of these, 2,931 (40.3%) switched therapy, 109 (1.5%) augmented therapy, and 4,233 (58.2%) maintained their antidepressant therapy. Antidepressant augmentation is a common practice to address comorbid anxiety symptoms, such as generalized anxiety disorder ( 16 ). However, the addition of a second agent introduces an increased risk of adverse events, particularly additive side effects and drug-drug interactions.

|

Close to two-thirds of the study participants in each cohort were female, and more than 60% of each cohort were from the South and West regions of the United States. The age group with the highest percentage of participants from each cohort was the 35–44 year group (32% of switchers, 28% of augmenters, and 33% of maintainers were in this age range). Percentages were similar across cohorts for each of the five age groups (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 years). The largest proportion of participants (approximately one-third) in each cohort was enrolled in a point of service (POS) plan, while the preferred provider organization (PPO) plan was the second most common plan type.

More than half of the study participants in each cohort had comorbid mental health conditions, and between 26% and 34% (depending on the cohort) were taking psychiatric medication, mainly anxiolytics. The MPR was lowest for persons who switched medication (39% versus 56% for maintainers). The average number of days that elapsed until therapy discontinuation was 90 for those who switched, 107 for those who augmented, and 142 for those who maintained their therapy. The mean number of days to switch or augment the index antidepressant in the postindex period was 269 for switchers and 281 for augmenters, and the mean number of total days' supply of index medication was 142 for switchers, 244 for augmenters, and 205 for maintainers.

Health care visits (emergency room, inpatient hospital visits, and ambulatory visits) for depression and for all causes in each cohort are presented in Table 2 . On the basis of Wilcoxon tests, the number of postindex visits was significantly different between the switchers and maintainers and between the augmenters and maintainers (p<.001).

|

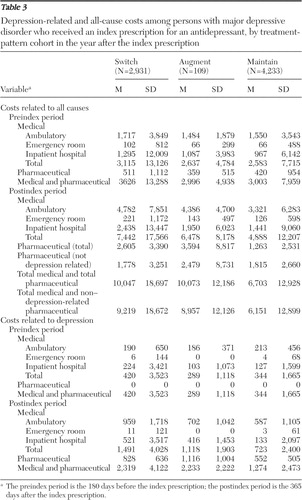

Postindex depression-related and all-cause health care costs by study cohort are reported in Table 3 . The mean costs between switchers and maintainers and augmenters and maintainers were significantly different (p<.001) on the basis of Wilcoxon tests. Persons who switched or augmented therapy had higher mean depression-related and all-cause costs than those who maintained therapy.

|

The number of days lost as a result of health care visits for depression (one-half day for each outpatient visit and one day for each day of inpatient stay) ranged from an average of 3.06±4.92 for maintainers to 4.86±5.77 for switchers and 4.16±4.22 for augmenters during the postindex period.

In terms of the costs associated with the number of days lost as a result of health care visits for depression, these results were calculated using the average wage for each census region as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the relevant time period. The mean costs of lost productivity per person (workdays lost as a result of weekday health care visits) for switchers was $680±$824, versus $437±$188 for maintainers and $587±$611 for augmenters. The costs were significantly different across the switcher and maintainer cohorts and the augmenter and maintainer cohorts on the basis of the results of mean Wilcoxon tests (p<.001). The mean costs of lost productivity per person as a result of health care visits for any cause were $2,081±$1,759 for switchers, $2,010±$1,554 for augmenters, and $1,424±$1,423 for maintainers.

The majority of claims were for short-term disability (accounting for 95% of claims for any-cause disability and 96% of depression-related disability), followed by long-term disability (9% and 11% of any-cause and depression-related disability claims, respectively), and finally, workers' compensation (5% of any-cause disability claims and <1% of depression-related disability claims). Note that these categories (long-term, short-term, and workers' compensation) are not mutually exclusive. Approximately 36% of all depression-related disability claims were filed by those who switched their medication, whereas only 27% of maintainers filed a depression-related disability claim and 22% of augmenters filed this type of claim.

Rather than relying on health care visits to estimate lost productivity, we used the total business days lost and wage replacement costs reported on disability claims. The results show that the total business days lost per person for depression was 136±167 days for switchers (N=102), 23±32 days for augmenters (N=2) and 80±114 days for maintainers (N=67), or in percentage terms, lost productivity was 70% higher for switchers than for maintainers. The wage replacement costs per person were $12,039±$17,650 for switchers versus $1,792±$2,534 for augmenters and $9,937±$12,867 for maintainers.

We used multivariate methods to analyze total costs related to depression, excluding costs for depression medications. Utilizing GLMs with a gamma distribution and log-link function, we investigated the relationship between medication adherence and cost and the association between treatment pattern and cost. Our results suggest that adherence, as measured by MPR, is not a significant predictor of total depression-related costs. Those who switched antidepressant therapy in the postindex period were more likely to have higher depression-related costs. Switchers had 1.92 times higher depression-related costs than those who maintained therapy (on the basis of relative risk). Differences were assessed at a 5% significance level. These results are presented in Table 4 . In terms of total health care costs those who switched had 1.42 times higher total costs than maintainers, and augmenters had 1.52 times higher total costs than maintainers ( Table 5 ). After the analyses controlled for baseline characteristics, mean total and depression-related health care costs, respectively, in the year after the index prescription were significantly greater for switchers ($9,288 and $1,388) and for augmenters ($9,350 and $1,027) than for maintainers ($6,151 and $723).

|

|

We also investigated factors that may be correlated with a depression disability claim by estimating a likelihood function. The dependent variable was whether the participant had a disability claim for depression (N=209). The same independent variables listed in Table 4 were used. Those who switched therapy were more likely to have a disability claim for depression than those who did not switch therapy (odds ratio=1.84, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.38–2.40).

To estimate the number of business days lost as a result of depression, a binomial regression model was used. The results of this analysis suggest that the participants who switched therapy had 1.8 times (CI=1.39–2.39) as many days lost than maintainers.

The estimation of wage replacement costs for depression disability was conducted using multivariate methods. The model selected was a GLM with a gamma distribution and log-link function. Participants who switched therapy had 1.66 times (CI=1.20–2.28) higher wage replacement costs than those who maintained therapy. Participants with higher preindex total costs had higher wage replacement costs. Mean total and depression-related productivity losses, respectively, were significantly greater for switchers ($2,081 and $680) and augmenters ($2,010 and $587) than for maintainers ($1,424 and $437).

Discussion

Depression is a very complex and difficult-to-treat disease with a significant burden composed of direct health care-related costs and indirect costs associated with factors such as reduced productivity, work days lost, and wage replacement costs.

Antidepressant pharmacotherapies are diverse and target a variety of neurochemical processes. Even when these therapies are effective in managing patients' depression, they are often associated with an array of unpleasant and even invalidating side effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and neurological problems. Side effects, as well as costs and the latency of therapeutic effects, contribute to medication regimen nonadherence ( 5 ). Nonadherence to antidepressant medication is associated with greater medical costs ( 17 ) and increased disability absence ( 18 ). Although we did not find that adherence was a significant predictor of total depression costs, the group in our analysis with the lowest adherence rate, patients who switched medications, also incurred significantly greater health care costs and costs resulting from lost productivity than patients who maintained therapy.

Intolerance, nonadherence, or lack of therapeutic effect may necessitate a change in treatment, which, as reported here, is also associated with greater costs. Patients' modified behavior (that is, switching or augmenting treatment as opposed to maintaining therapy) was associated with higher costs to patients, insurers, and employers. The increased costs arose not only from health care visits and pharmacy prescriptions but also from the costs associated with the workplace. Patients who switched therapy and filed a disability claim experienced higher overall and depression-related costs. Those who switched also had more days of depression-related absences from the workplace and higher wage replacement costs.

Our findings suggest that patients who begin therapy with an antidepressant that is tolerable and effective for them will incur fewer costs than patients who require a change. This is consistent with previous studies that found that depression-related health care costs were significantly greater for patients who switched medication than for those who did not ( 19 ). However, modifying treatment might be cost-saving relative to ineffective treatment: a Finnish study reported that many depressed patients receiving disability compensation had not attempted sequential antidepressant trials or received psychotherapy, suggesting that disability payments could be minimized with improved care, including expanded therapeutic efforts ( 20 ).

This analysis considered only medication, but cognitive therapy can also be used for augmentation or a switch. A randomized clinical study comparing second-line cognitive therapy with second-line antidepressant therapy found that efficacy was similar between the two treatments ( 21 ).

As with any retrospective analysis of administrative claims data, there are limitations that should be considered. First, presence of a claim for a filled prescription does not indicate that the medication was consumed or that it was taken as prescribed, nor does it address the reasons for selecting a particular therapy or for altering treatment. We attempted to account for underlying biases in the cohorts, such as differences in disease severity, by including comorbid conditions and other psychiatric medications in the analyses. Second, medications filled over the counter or provided as samples by the physician will not be observed in the claims data. Third, presence of a diagnosis code on a medical claim does not indicate presence of disease, because the diagnosis may be incorrectly coded or included as rule-out criteria rather than actual disease. Finally, certain information that could have an effect on study outcomes is not readily available in claims data, such as certain clinical and disease-specific parameters and the quality of care delivered in a particular community.

Conclusions

Utilizing retrospective claims data analysis, we looked at health care and productivity-related costs associated with depression for three cohorts of patients taking antidepressants (switchers, augmenters, and maintainers). Patients who modified the course of their antidepressant therapy incurred higher health care and labor-related costs than those who maintained treatment. Pharmacologic agents that reduce the need for therapy changes, perhaps because of their enhanced effectiveness or better tolerability, may have a beneficial impact on depression-related costs.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Schultz was a paid consultant to i3 Innovus while conducting this research and contracted with Sanofi Aventis to conduct the research for this study. Dr. Joish is an employee of Sanofi Aventis.

1. Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al: The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:1465–1475, 2003Google Scholar

2. Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al: Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 289:3135–3144, 2003Google Scholar

3. Birnbaum HG, Leong SA, Greenberg PE: The economics of women and depression: an employer's perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders 74:15–22, 2003Google Scholar

4. Greenberg P, Corey-Lisle PK, Birnbaum H, et al: Economic implications of treatment-resistant depression among employees. Pharmacoeconomics 22:363–373, 2004Google Scholar

5. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision): American Psychiatric Association. American Journal of Psychiatry 157(suppl 4):1–45, 2000Google Scholar

6. Thase ME, Rush AJ: Treatment-resistant depression; in Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Edited by Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ. New York, Raven, 1995Google Scholar

7. Kroenke K, West SL, Swindle R, et al: Similar effectiveness of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline in primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA 286:2947–2955, 2001Google Scholar

8. Ruhe HG, Huyser J, Swinkels JA, et al: Switching antidepressants after a first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:1836–1855, 2006Google Scholar

9. Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al: Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Controlled Clinical Trials 25:119–142, 2004Google Scholar

10. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al: Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. New England Journal of Medicine 354:1231–1242, 2006Google Scholar

11. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al: Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. New England Journal of Medicine 354:1243–1252, 2006Google Scholar

12. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al: Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical Care 43:1073–1077, 2005Google Scholar

13. Duan N, Manning WG Jr, Morris CN, et al: A comparison of alternative models for the demand for medical care. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 1:115–126, 1983Google Scholar

14. Manning WG: The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. Journal of Health Economics 17:283–295, 1998Google Scholar

15. Mullahy J: Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and the two-part model in health econometrics. Journal of Health Economics 17:247–281, 1998Google Scholar

16. Lam RW, Wan DDC, Cohen NL, et al: Combining antidepressants for treatment-resistant depression: a review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:685–693, 2002Google Scholar

17. Cantrell CR, Eaddy MT, Shah MB, et al: Methods for evaluating patient adherence to antidepressant therapy: a real-world comparison of adherence and economic outcomes. Medical Care 44:300–303, 2006Google Scholar

18. Burton WN, Chen C-Y, Conti DJ, et al: The association of antidepressant medication adherence with employee disability absences. American Journal of Managed Care 13:105–112, 2007Google Scholar

19. Khandker RK, Kruzikas DT, McLaughlin TP: Pharmacy and medical costs associated with switching between venlafaxine and SSRI antidepressant therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 14:426–441, 2008Google Scholar

20. Honkonen TI, Aro TA, Isometsä ET, et al: Quality of treatment and disability compensation in depression: comparison of 2 nationally representative samples with a 10-year interval in Finland. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68:1886–1893, 2007Google Scholar

21. Thase ME, Friedman ES, Biggs MM, et al: Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: a STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:739–752, 2007Google Scholar