Assessing Nurse-Initiated Care in a Mental Health Crisis Assessment and Treatment Team in Australia

Legislative recognition of nurse practitioners in Victoria, Australia, is detailed in the Health Professionals Regulation Act of 2005 ( 1 ). An endorsed nurse practitioner is legally entitled to practice in areas previously under the exclusive domain of physicians, including prescribing medication, ordering diagnostic tests, admitting and discharging patients, making referrals to specialist physicians, and authorizing certificates that approve absence from work or unemployment benefits.

Endorsement as a nurse practitioner in Victoria requires the registered nurse to have completed a master's degree in nursing that includes specific courses in pharmacology. In addition, applicants must have a minimum of two years of professional nursing experience ( 2 ). However, because the nurse is expected to demonstrate advanced clinical practice and skills and expertise in research and leadership, the duration of experience is likely considerably longer.

Recent government and independent inquiries have noted the severe shortage of mental health professionals ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). Inadequate numbers of psychiatrists and other medical personnel can delay initiation of medical treatment that may lead to deterioration in a patient's mental state, placing additional strain on individuals with mental illness and their families ( 4 , 5 ).

A number of studies examining the role of nurse practitioners in primary care and emergency departments found no significant differences in health outcomes between patients treated by a nurse practitioner and those treated by a physician and a high level of satisfaction with care initiated by nurse practitioners ( 5 ). Kinnersley and colleagues ( 6 ) conducted a study of 1,368 patients attending general practices in the United Kingdom and found that patients treated by nurse practitioners and those treated by physicians had similar levels of satisfaction and similar treatment outcomes and duration of consultations. Furthermore, patients reported receiving more information about their illnesses from nurse practitioners. A similar U.S.-based study on primary care of 1,316 patients found no significant differences in patient satisfaction, service utilization, or health status six months after treatment when services were provided by a nurse practitioner or by a physician ( 7 ).

A Cochrane review found no significant differences between quality of care and health outcomes when primary care was provided by nurse practitioners or by physicians ( 8 ). Satisfaction with treatment provided by nurse practitioners was as high or higher than satisfaction with that provided by physicians. The potential of nurse practitioners to save health care dollars was also identified.

However, there has been no evaluation of the role of nurse practitioners in mental health services. An Australian qualitative study by Wortans and colleagues ( 9 ) noted a lack of systematic investigation of the role of nurse practitioners in the mental health field. The study suggested that consumers had a high level of satisfaction with and confidence in mental health care led by a nurse practitioner candidate. The study highlighted the communication skills of the nurse practitioner candidate, which enhanced patients' understanding and facilitated the therapeutic relationship. Participants also noted that the nurse practitioner candidate spent more time with them than physicians.

The Victorian Department of Human Services (DHS) funded a number of pilot demonstration projects in a range of specialty areas of nursing practice to assess the relevance and effectiveness of nurse practitioner roles. The research described here was conducted as part of a demonstration project to assess the value of a nurse practitioner role in a specialist mental health crisis assessment and treatment team (CATT).

Methods

This study was conducted in a CATT of a major mental health service, the Northern Area Mental Health Service. The CATT is a rapid-response mobile community outreach service designed to assess any person with an acute crisis requiring specialist mental health intervention. It serves northern Melbourne, which covers metropolitan to semirural communities (catchment population of approximately 260,000).

In phase I of the study (February 2005 to May 2005) the role of a nurse practitioner candidate in brief community-based treatment in a CATT was evaluated. His clinical decision-making skills were evaluated weekly by a consultant psychiatrist. All CATT clients were invited to participate in this stage. Similarly, in phase II (September 2005 to September 2006) all CATT clients were invited to participate. Interested parties were provided with a written explanation of the study and a consent form. Participants were randomly assigned to care initiated by the nurse practitioner candidate or to treatment as usual in which care was initiated by a trainee psychiatrist. The study was approved by the NorthWestern Mental Health Research and Ethics Committee.

The term "nurse practitioner candidate" is used to refer to the nurse involved in the project because "nurse practitioner" in Victoria is legally protected and can be used only by a nurse who is officially endorsed as such on the nursing register. During the DHS demonstration project, the candidate performed nurse practitioner roles, such as prescribing medications and ordering tests, under the supervision of the consultant psychiatrist. The nurse practitioner candidate could not perform these tasks autonomously because he had not yet earned official endorsement.

All CATT clients are initially assessed by two mental health clinicians from the multidisciplinary team, which consists of nurses, psychologists, social workers, and occupational therapists. After assessment, the CATT may choose to admit an individual to a hospital, refer him or her back to the referrer with recommendations for treatment, or accept the client for brief community-based treatment to stabilize the clinical situation and avoid hospitalization. The community-based treatment provided by the CATT generally lasts about two weeks and involves daily or almost daily clinical monitoring, administration of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, and where appropriate, family support and psychoeducation.

The day after this initial assessment patients in the treatment-as-usual group were seen by the trainee psychiatrist, who provided a full assessment and formulated a care management plan. The trainee psychiatrist could administer medications, order evaluations, authorize a certificate for time off work, and refer to other specialist health care providers. The care plan was reviewed by the consultant psychiatrist. The care initiated by the trainee psychiatrist was provided by the CATT. As per usual practice, the patient was not seen again by the trainee psychiatrist until the next week unless there were significant clinical concerns.

For patients assigned to the group in which the nurse practitioner candidate initiated care, the candidate took the role of the trainee psychiatrist. Thus he fully assessed the patient and formulated a treatment plan, which was reviewed immediately by the consultant psychiatrist to avoid a delay in treatment. Similarly, the CATT implemented the treatment initiated by the nurse practitioner candidate. The candidate had no significant involvement with patients in the treatment-as-usual group.

Patients in both groups received daily visits by CATT clinicians during the first week of the study. After seven days, patients in the nurse-initiated care group reverted to treatment as usual. The day 7 transfer was designed to mimic the operation of actual clinical practice. It is not anticipated that a nurse practitioner would become a substitute for a psychiatrist but rather that treatment would be initiated by the nurse practitioner and the patient would be seen by a psychiatrist, which typically occurs within one week.

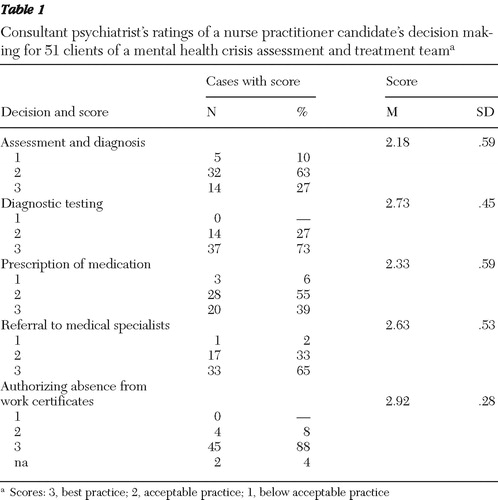

For three months before data collection, the nurse practitioner candidate had weekly supervision sessions with the consultant psychiatrist in which cases of clients for whom the candidate had made assessments were discussed. The candidate's clinical skills were rated in five categories: assessment and diagnosis, diagnostic testing, prescription of medication, referral to medical specialists, and approval of certificates for absence from work. The consultant gave a rating of 3 for best practice (consistent with effective practice for a trainee psychiatrist and not requiring any significant modification) and a rating of 2 for acceptable practice (practice that is safe and appropriate and does not require remedial action but for which there is scope for further improvement). A rating of 1 was given for below acceptable practice (unsafe or inappropriate practice that requires remedial action—for example, not considering the use of an adjunctive anxiolytic in a patient with agitated depression).

At the initial assessment the Health of Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS) was completed for all patients. It is a broad measure of mental health and social functioning for people with mental illness. It was again administered upon discharge from the CATT for the treatment-as-usual group and at seven days for the intervention group. At the discharge or transfer point, participants also completed the Consumer Satisfaction Measurement Tool (CSMT). When caregivers were available, they were asked to complete the Carer Satisfaction Measurement Tool (CaSMT). The CSMT was adapted from the Nurse Practitioner Satisfaction Instrument ( 10 ) and the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire to suit the clinical environment of the study. The CaSMT was adapted from the CSMT. [An appendix showing the CSMT and CaSMT is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Data on age, gender, country of birth, and psychiatric diagnosis were collected, as were two treatment outcome variables: duration of treatment with the CATT and final disposition—either hospital admission (psychiatric or medical) or transfer back to an appropriate service provider after effective community treatment. Consumers admitted to the hospital for any reason were not surveyed at the second time point, because hospital admission may have influenced the outcome measures. Also, it may have indicated that the patient's illness was not amenable to community treatment.

Mean differences between the two groups on the CSMT and the CaSMT scores and the treatment outcome variables related to the duration of CATT treatment were assessed with t tests. Paired t tests were used to assess mean differences in the HoNOS scores between admission and discharge (control group) or transfer to treatment as usual (intervention group). Chi square and Fisher's exact tests assessed differences between groups on diagnosis and final disposition. All data were analyzed using SPSS, version 11.

Results

The nurse practitioner candidate achieved at least a rating of acceptable from the consultant psychiatrist for all 51 patients in the areas of diagnostic testing and authorizing absence from work ( Table 1 ). For assessments and diagnosis, he achieved an acceptable rating for 90% of cases, but five cases required remedial action. Regarding prescription of medications, 94% of his decisions were acceptable, and three required changes. For referral to a medical specialist, 98% were acceptable, with one case requiring remedial action.

|

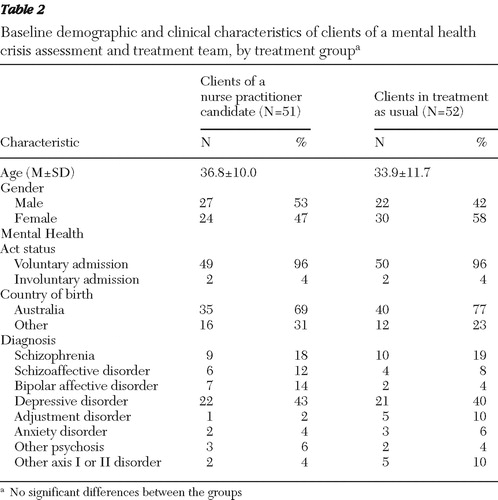

A total of 103 patients were recruited, with 51 assigned to the intervention group and 52 to the control group. In the intervention group there were 27 males (53%), compared with 22 (42%) in the control group. The mean±SD ages of the two groups did not differ significantly (36.8±10.0 and 33.9±11.7 years, respectively). No significant group differences were found in voluntary or involuntary status, country of birth, or diagnosis. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2 .

|

The median duration of treatment for the intervention group was 11 days (range, two to 35), consisting of the initial seven days in the intervention group and the remaining time in treatment as usual. This compared with ten days (range, two to 36) for the control group. The difference was not statistically significant. During treatment, ten participants from the intervention group and five from the control group required hospitalization (not a significant difference).

Mean HoNOS scores were not significantly different between the groups at baseline, and scores for both groups significantly improved with treatment (baseline score=12.2±4.8 for the control group and 12.7±4.9 for the intervention group; follow-up score=5.5±5.1 for the control group and 7.2±5.1 for the intervention group) (difference for the control group: t=7.90, df=51, p<.001; difference for the intervention group: t=6.90, df=50, p<.001). (Possible HoNOS scores range from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating a greater severity of mental illness. Scores of 12 or more are considered to indicate severe illness, and scores of less than 6 are considered to indicate mild illness.

CSMT and CaSMT scores were not significantly different between groups (CSMT score=4.06±.61 for the control group and 4.22±.61 for the intervention group; CaSMT score=4.11±.9 for the control group [N=25] and 4.21±.38 for the intervention group [N=30]). Possible scores on both range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Discussion

This is the first known study to compare outcomes of and satisfaction with treatment provided by a crisis assessment and treatment team that was initiated either by a nurse practitioner candidate or by a psychiatrist. No between-group differences in these measures were found either before or after treatment provided by the CATT. Although a greater number of participants in the intervention group required hospitalization (ten patients, compared with five patients in the control group), the difference was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the twofold increase in the hospitalization rate warrants observation in any large-scale replication.

The mean HoNOS score was higher for the intervention group postintervention (7.2, compared with 5.5 for the control group), although the difference was not statistically significant. This difference most likely reflects the different time points at which data were collected—at day 7 after initiation of treatment for the intervention group and at time of CATT discharge for the control group (median of ten days). The longer treatment duration for the control group likely resulted in greater improvement. This methodological difference was unavoidable because clinical staff were used to collect these data. The reason for the difference can be definitively resolved only with a large-scale replication study in which data are collected at the same time point.

Overall, these findings concur with those from primary and emergency care settings ( 6 , 7 , 11 , 12 ) in suggesting that nurse practitioners are able to initiate care within treatment teams that results in outcomes comparable to those of treatment initiated by physicians. Similarly, consumer and caregiver satisfaction levels were similar for both groups, which supports previous findings that satisfaction with the services of a nurse practitioner tends to be at least equal to satisfaction with routine medical treatment.

An additional feature of this study is the assessment of the nurse practitioner candidate's decision making and treatment formulation by the consultant psychiatrist. Although a blinded design was not possible, it provided the opportunity for a greater understanding of the nurse's capacity to function in specific roles. This adds an additional depth to the research in that the focus was on process—rather than entirely on outcomes, as has been the focus of most previous work. In this regard, the nurse practitioner candidate's clinical decision making was rated for the most part at an acceptable level. It would be anticipated that with greater clinical experience and regular supervision this would continue to improve, as is the case for physicians ( 13 ).

These findings are particularly significant in light of the current shortage of physicians in mental health services ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). More immediate and responsive treatment can be initiated by a nurse practitioner, avoiding delays and potentially avoiding exacerbation or deterioration of the patient's psychiatric condition. This is particularly important in rural areas, where the shortage of qualified medical staff is acute because of difficulties in recruitment and retention.

The legal framework for endorsement of registered nurses as nurse practitioners is now in place in Victoria ( 1 ), and appropriately qualified and experienced mental health nurses can become nurse practitioners and can further contribute to the provision of high-quality mental health service delivery in the community by facilitating early initiation of treatment.

It is crucial that psychiatrists and mental health nurses actively contribute to discussions about the roles of nurse practitioners. Concerns have been raised that nurse practitioners may become substitutes for doctors because of the expansion of nursing into areas traditionally restricted to trained physicians. It is important to clarify that in the study presented here care was primarily delivered by a team of mental health professionals, and therefore it addresses only whether an initial evaluation by a nurse practitioner can produce outcomes comparable to treatment as usual within the CATT context.

The study has limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the sample was relatively small, and only a limited range of outcome measures was used. Furthermore, the study was conducted in only one mental health service, with only one nurse practitioner candidate. The extent to which the findings are valid and can be generalized to other crisis assessment teams and other mental health settings is therefore limited. Because the study was conducted in a metropolitan-semirural area, the findings cannot automatically be applied to rural and remote areas, where a pressing need for nurse practitioners is evident. An expanded replication is required to more confidently determine the impact of nurse practitioner roles on patient care and satisfaction with service delivery.

Conclusions

This study was conducted in a CATT in Melbourne. A quasi-experimental method was used to compare outcomes of and satisfaction with treatment that was initiated by a nurse practitioner candidate and by a medical practitioner. No significant differences were evident between the control and intervention groups. The nurse practitioner role may make an important contribution to the initiation of safe and effective mental health crisis care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors acknowledge the Victorian Department of Human Services for providing funding for a pilot Nurse Practitioner Demonstration Project. The authors also acknowledge the following people who contributed to the successful completion of this work: Stephen Brown, Chris Gibbs, Karla Gough, Robyn Humphries, Brian Jackson, and Teresa Kelly.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Health Professionals Regulation Act, Victorian Government, Parliament of Victoria, 2005Google Scholar

2. Process for Nurse Practitioner Endorsement. Melbourne, Nurses Board of Victoria, 2008Google Scholar

3. Australia's Health Workforce Productivity Commission. Canberra, Australian Government Productivity Commission, Commonwealth of Australia, 2005Google Scholar

4. Not for Service: Experiences of Injustice and Despair in Mental Health Care in Australia. Deakin, Australian Capital Territory, Mental Health Council of Australia, 2005Google Scholar

5. A National Approach to Mental Health—From Crisis to Community. Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia, Senate Select Committee on Mental Health, 2006Google Scholar

6. Kinnersley P, Anderson E, Parry K, et al: Randomised controlled trial of nurse practitioner versus general practitioner care for patients requesting "same day" consultations in primary care. British Medical Journal 320:1043–1048, 2000Google Scholar

7. Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, et al: Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: a randomized trial. JAMA 17:8–17, 2000Google Scholar

8. Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, et al: Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews CD001271, 2005Google Scholar

9. Wortans J, Happell B, Johnstone H: The role of the nurse practitioner in psychiatric/mental health nursing: exploring consumer satisfaction. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 13:78–84, 2006Google Scholar

10. Knudtson N: Patient satisfaction with nurse practitioner service in a rural setting. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 12:405–412, 2000Google Scholar

11. Shum C, Humphreys A, Wheeler D, et al: Nurse management of patients with minor illnesses in general practice: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 320:1038–1043, 2000Google Scholar

12. Venning P, Durie A, Roland M, et al: Randomised controlled trial comparing cost effectiveness of general practitioners and nurse practitioners in primary care. British Medical Journal 320:1048–1053, 2000Google Scholar

13. Kilminster S, Cottrell D, Grant J, et al: Effective educational and clinical supervision. Medical Teacher 29:2–19, 2007Google Scholar