Apathy and Functioning in First-Episode Psychosis

The high risk of prominent functional decline makes schizophrenia one of the most disabling disorders affecting young people ( 1 , 2 ). Negative symptoms are found to be one of the major predictors of poor functioning across studies of chronic patients ( 3 , 4 , 5 ) and patients with first-episode psychosis ( 6 , 7 ). The importance of this topic is illustrated by the NIMH-MATRICS (National Institute of Mental Health-Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia) consensus statement on negative symptoms, which concluded that there has been limited progress in the development of effective treatments ( 8 ). Those behind the consensus statement and other clinical researchers have argued that the research focus needs to shift from regarding negative symptoms as a unitary construct to studying the different components or subsymptoms that underlie the negative symptom area ( 9 , 10 , 11 ).

The concept of negative symptoms is old; it was reintroduced as a meaningful concept at the end of the 1970s to explain the heterogeneity of symptoms and outcome in schizophrenia ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). It is known that negative symptoms are not a unitary construct but are a syndrome made up of different subsymptoms, mainly apathy and avolition, anhedonia, alogia, asociality, flat affect, and inattention ( 14 ). Our knowledge of the underlying mechanisms behind these subsymptoms is limited ( 8 ).

Apathy is a neuropsychiatric symptom associated with dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex or its subcortical connections ( 15 , 16 , 17 ). Apathy is found to be a common symptom in a broad range of neuropsychiatric and brain disorders, such as Alzheimer's dementia ( 18 ), Parkinson's disease ( 19 ), and Huntington's disease ( 20 ), and in traumatic brain injury ( 21 ). Kraepelin ( 22 ) considered apathy to be the core symptom of the chronic stages of schizophrenia, a view that has held and receives emphasis today ( 23 , 24 , 25 ).

One challenge for the study of negative symptoms and the subsymptoms has been the lack of valid and reliable rating scales for use in clinical settings ( 11 , 26 ). The Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) was developed to assess apathy in neuropsychiatric disorders ( 27 ) and has been widely used in studies of apathy ( 19 , 21 , 28 ). In the AES, apathy is defined as "lack of motivation or goal-directed behavior not attributable to diminished level of consciousness, cognitive impairment or emotional distress." The scale has been validated for use across different medical disciplines and recently also for patients with a first episode of psychosis ( 29 ) and chronic schizophrenia ( 30 ). The availability of a well-tried assessment method for apathy makes it a good candidate for exploration of the mechanisms behind the development of negative symptoms.

The clinical importance of negative symptoms more broadly defined is based on their clear association with functional decline. Deeper knowledge about their underlying mechanisms will thus aid in understanding what lies behind the functional decline itself. To evaluate whether apathy is a good model for understanding functional decline, it is important to know also whether apathy as a symptom is associated with decreased functioning. Apathy has been found to be clearly related to poor functioning in several neuropsychiatric disorders ( 18 , 31 ). The only study that has addressed the relationship between apathy and functioning in schizophrenia reported that apathy, more than other symptoms, predicted poor functioning in a group of chronic patients, indicating an association at least in this patient group ( 30 ).

However, to avoid the possible confounding influences of treatment failures and social defeat in chronic schizophrenia, it is of particular interest to study the relationship between apathy and functioning in a patient group experiencing first-episode psychosis. The aim of this study was thus to answer the following four questions: Do first-episode psychosis patients experience higher levels of apathy than persons without psychiatric disorders? Do first-episode psychosis patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders have higher levels of apathy than patients with other first-episode psychotic disorders? What other clinical characteristics (outside of diagnosis) are associated with apathy in the early treatment phase? And finally, to what degree does apathy contribute to functional loss among first-episode psychosis patients?

Methods

Participants

Patient group. Included in the study were 103 consecutively recruited first-episode psychosis patients who had given written informed consent to participate in the ongoing Thematically Organized Psychosis (TOP) research study. Patients were recruited between July 2004 and July 2006 as they were coming in for treatment of their first-episode psychosis, either as inpatients or outpatients, at three major hospitals in Oslo, Norway. All hospitals are catchment based, giving psychiatric service to two-thirds of the city's population. Patients were eligible for the study if they were between 18 and 65 years old, had a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS), delusional disorder, brief psychosis, or major depressive or bipolar I disorder with mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms.

All of the clinical assessments, including assessment of premorbid function and the duration of untreated psychosis, were made after the start of adequate treatment and the establishment of a stable phase; hence, patients could be included in the study up to 52 weeks after start of adequate treatment. The duration of untreated psychosis was measured from the first week in which the patient had psychotic symptoms (a rating of 4 or more on Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] items P1, P3, P5, P6, or G9) until the first week of adequate antipsychotic treatment, defined as either admission to a hospital or initiation of adequate antipsychotic medication.

Healthy control group. The 62 persons forming the healthy control group consisted of persons randomly selected from statistical records in the same catchment areas as the study patients. They were mailed an invitation to participate in the study. The participants were screened with the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders ( 32 ) and were excluded if they or any of their close relatives had a lifetime history of a serious psychiatric disorder (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression), if they had a history of medical problems thought to interfere with brain function (hypothyroidism, uncontrolled hypertension, or diabetes), or had recent cannabis use (used in the past three months).

General clinical assessment

Symptoms were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview of the PANSS ( 33 ). Repeated factor analyses have consistently indicated that the PANSS measures five symptom dimensions, but with some variations in the composition of the dimensions in the different studies ( 34 ). We chose to use the components based on Emsley and colleagues' ( 35 ) factor analysis of PANSS because they based that analysis on a first-episode psychosis sample. The components represent positive (PANSS-POS), negative (PANSS-NEG), disorganized (PANSS-DIS) depressive (PANSS-DEPR), and excited (PANSS-EXC) symptoms. In the follow-up analysis, the items included in the PANSS-NEG (N1, N2, N3, N4, N6, G7, G13, and G16) were used to represent different aspects of negative subsymptoms.

Assessment of apathy

Apathy was assessed by the AES. The AES has three versions with identical questions but administered to different respondents: clinician (AES-C), patient or self (AES-S), and informant (AES-I) ( 27 ). All three versions have 18 identical questions to be answered on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0, not at all; 4, very much). Questions include "Are you interested in things?" "Is it important for you to get things done during the day?" "Do you spend time doing things that interest you?" and "Do you feel motivated?" On the AES-S, the respondents make their own direct assessments. On the AES-C, the respondents are interviewed to facilitate probing and to evaluate the validity of the respondent's report (because apathy often coincides with disorders of insight and compromised self-evaluation). The clinician's rating is not based on observation of functioning; it is based only on information about the respondent's feelings and experiences. For the control group we had no reason to expect invalid information and used only the self-report form (AES-S). Both the self-report and clinician-rated forms were used for the patient group to avoid the risk of underreports of amotivation. The two scales were highly intercorrelated (r=.6, p<.01).

We have previously shown that a shortened 12-item form of the AES-C gave a better assessment of apathy than the full 18-item version in a first-episode psychosis population ( 29 ). The abridged version for both the clinical (AES-C-Apathy) and the self-rated (AES-S-Apathy) versions was therefore used in this study. On both versions a score of 27 was used as the cutoff value for indicating clinical apathy; it was two standard deviations (2 SD=8.6) above the mean sum scores (mean=18.0±4.3) of AES-S-Apathy for the control group.

Diagnostic assessment

Diagnosis was assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) ( 36 ). For the statistical analysis, patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (N=45), schizophreniform disorder (N=10), and schizoaffective disorder (N=2) were combined into a schizophrenia spectrum group. Those with major affective disorder with mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms (N=14) and bipolar I disorder with mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms (N=3) were combined to form an affective psychosis group. Persons with psychosis NOS (N=20), brief psychosis (N=7), and delusional disorder (N=2) were in the "other psychosis" group.

Assessment of drug use

Drug use was assessed with the Alcohol and Drug Use Scale, which separately measures drug and alcohol use in the past six months ( 37 ). The scores range from 1 to 5 (1, no use; 2, use without impairment; 3, abuse; 4, dependence; and 5, dependence with institutionalization).

Assessment of premorbid functioning

Premorbid functioning was assessed with the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS) ( 38 ). The premorbid phase was defined as the time from birth until six months before the onset of psychosis. The premorbid phase is divided into four life periods: childhood (up to 11 years), early adolescence (12–15 years), adolescence (16–18 years), and adulthood (19 years and older). The scores range from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating the best level of functioning and 6 the worst. Several studies have confirmed two basic dimensions in the PAS, the social and the academic clusters ( 39 , 40 ). We used the method described by Larsen and colleagues ( 39 ) when calculating separate sum scores for PAS social cluster functioning and PAS academic cluster functioning ( 39 ), and we used the method of Haahr and colleagues ( 41 ) to calculate changes in functioning: PAS social change and PAS academic change scores.

Assessment of global functioning

The function score from the split version of the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF-F) was used to measure change in global functioning ( 42 ). The split version has been found to discriminate adequately between symptoms and function ( 43 ) and has been used in other studies of first-episode psychosis ( 44 ). The GAF-F has a continuous scale ranging from 1 to 100, where 1 indicates the poorest and 100 the best functioning. The ratings are based on the assessor's evaluation of the patient's functioning in concrete areas such as work, social contacts, and independent living.

Procedures

All participants gave written informed consent to participate, and the Regional Committee approved the study for medical research ethics and for meeting standards of the Norwegian Data Inspectorate. The data file has received an audit certificate from the Center for Clinical Research at Ullevål University Hospital.

The three investigators who carried out the assessments completed the common training and reliability program in the TOP study group. They were trained in the use of the AES by scoring videos of interviewed patients. Scoring was supervised by two experienced clinicians who had used the scale with other patient groups ( 21 ). The reliability testing of the AES was completed by blind-rating seven live interviews with randomly chosen patients from the study sample. The SCID training was based on the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), training program ( 45 ) and was supervised by UCLA researchers. For DSM-IV diagnostics, mean overall kappa for the standard diagnosis of training videos was .77, and the mean overall kappa for a randomly drawn subset of study patients was also .77 (95% confidence interval [CI]=.60–.94). Interrater reliability was acceptable, with an intraclass coefficient (ICC) of 1.1 for the different subscales: PANSS positive subscale, ICC=.82 (CI=.66–.94); PANSS negative subscale, ICC=.76 (CI=.58–.93); PANSS general subscale, ICC=.73 (CI=.54–.90); GAF-F, ICC=.85 (CI=.76–.92); and AES-C, ICC=.98 (CI=.92–.99).

Statistical analyses

Preliminary analyses were performed to examine the distribution of each variable. Logarithmic transformation was conducted when appropriate. Only duration of untreated psychosis required transformation to its natural logarithm, because of skewed data distribution. All tests were two-tailed, with a preset level of significance of .05. Descriptive data are presented either by means and standard deviations or by medians and ranges when appropriate. Bivariate correlations were calculated as Pearson product-moment coefficients (r). Independent-samples t tests, paired-samples t tests, and one-way analyses of variance with post hoc Scheffé's test were used to analyze differences between groups.

Because several of the characteristics associated with measures of apathy and functioning (or both) were interdependent, the questions of which clinical characteristics were independently related to apathy in the early treatment phase and to what degree apathy contributed to worse functioning of first-episode psychosis patients were explored through two separate multiple linear regression analyses. The independent variables were chosen for the regression analyses if they had a statistically significant correlation (p<.05) with the dependent variable in question (AES-C-Apathy and GAF-F, respectively).

For our third research question (which clinical characteristics are associated with apathy in early treatment), the independent variables were entered hierarchically in order of their lifetime appearance, with the first step representing background and premorbid variables (gender, age, and premorbid adjustment), the second step representing diagnosis, and the third step giving information about current status (drug and alcohol use, antipsychotic medication, and symptoms). PANSS-NEG was not part of the analysis, because apathy is also part of that measure. For the fourth research question (to what degree apathy independently contributed to functional loss), symptoms were entered in order of the strength of their correlation with functioning in the bivariate analyses, with AES-C-Apathy on the last step after analyses controlled for the influence of all other current symptoms. The final models were checked for violation of assumptions and for the effects of outliers and influential observations. Analyses were done using the SPSS, version 15.0 for Windows.

Results

Demographic characteristics of patients and control group

The demographic and diagnostic characteristics and symptom distribution of the patient group are presented in Table 1 . There was no significant difference in gender distribution between the patient group and the control group, but the control group was significantly older (mean difference of 4.7 years, CI=1.6–.9, p=.002) and had slightly more years of education (mean difference of .9 year, CI=.2–1.7, p=.03) ( Table 1 ).

|

Level of apathy

There was a statistically significant difference between the healthy control group and first-episode psychosis patients in the mean AES-S-Apathy score (t=-9.7, df=162, p<.001) ( Table 1 ). Based on the predefined cutoff score of 27 for being clinically apathetic, 55 (53%) of the first-episode psychosis patients were rated apathetic by the clinician (AES-C-Apathy) and 56 (54%) rated themselves (AES-S-Apathy) as being apathetic, compared with only two persons (3%) from the healthy control group.

Level of apathy in different diagnostic groups

There was a significant group difference in AES-C-Apathy score (F=4.16, df=2 and 100, p=.02) between the diagnostic groups. Post hoc comparison (Scheffé test) showed that this difference reached the level of statistical significance (p=.03) for the schizophrenia spectrum group (M±SD=28.3±6.4) and the "other psychosis" group (24.1±8.2). Although the numerical score for the patients with affective psychosis (28.8±6.3) was nearly identical to that of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, it was not statistically significantly different from the score of patients with "other psychosis," probably because of a small sample (that is, the possibility of a type II error cannot be ruled out).

Patient characteristics and relationship to apathy

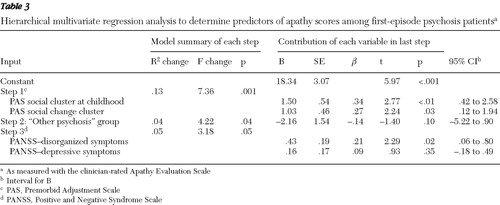

None of the following had an independent significant relationship with AES-C-Apathy: gender, current age, age at start of psychosis, duration of untreated psychosis, use of antipsychotic medication, use of alcohol or drugs, or positive symptoms (PANSS-POS score) ( Table 2 ). In addition, the PAS academic cluster during childhood and PAS for academic change did not have a significant association with AES-C-Apathy and were thus not entered into the subsequent hierarchical regression analyses. Of the three diagnostic categories, only "other psychosis" was significantly correlated (negatively) with AES-C-Apathy. Of the symptoms measured by PANSS, only disorganized and depressive symptoms were significantly correlated (positively) with AES-C score ( Table 2 ). These independent variables, together with PAS social cluster during childhood and PAS social change, were thus entered into a hierarchical regression analysis in three steps ( Table 3 ). This model explained 18% of the variance in the AES-C-Apathy score (R=.46, adjusted R 2 =.18; F=5.33, df=5 and 97, p<.01), with all steps indicating significant contributions to level of apathy. When the combined contribution of the independent variables was examined, PAS social cluster during childhood made the strongest significant contribution, together with PANSS-DIS and PAS social change, whereas the influence of a diagnosis of "other psychosis" and PANSS-DEPR became nonsignificant ( Table 3 ).

|

|

Apathy and functioning

GAF-F scores were significantly negatively associated not only with AES-C-Apathy but also with PANSS-NEG, PANSS-POS, and PANSS-DIS symptom scores ( Table 2 ). These variables were entered into the hierarchical regression analysis with GAF-F score as the dependent variable ( Table 4 ). Even when all other symptoms were controlled for, AES-C-Apathy showed a significant contribution when entered at the last step ( Table 4 ). This model explained 37% of the variance of the GAF-F scores (R=.63, adjusted R 2 =.37; F=15.9, df=4 and 98, p<.001).

|

When the combined contribution of the different independent variables were studied together, only PANSS-POS and AES-C-Apathy made significant independent contributions, whereas the contribution of PANSS-NEG and PANSS-DIS became nonsignificant ( Table 4 ). To study whether the aspects of different negative subsymptoms represented by the eight items comprised by the PANSS-NEG component had independent contributions, we repeated this analysis but entered these items at the first step of the hierarchical regression ( Table 5 ). The total explanatory power of this model was not changed compared with the original solution, and only flat affect, in addition to PANSS-POS and AES-C-Apathy, made a significant contribution to functioning (R=.66; adjusted R 2 =.37; F=6.44, df=11 and 91, p<.001).

|

Discussion

The first important finding of this study is that apathy was a prevalent symptom for first-episode psychosis patients. We found that more than 50% of the participating patients were clinically apathetic, with the level of apathy significantly higher in the patient group than in the control group. The mean level of apathy in this study also appears to be higher than levels found among patients with left- or right-sided acquired brain injury ( 21 ), similar to levels found among hypoxic brain-injury patients ( 21 ) but lower than levels found among patients with Alzheimer's dementia ( 27 ) (all measured by the AES). This finding underlines that the level of apathy among first-episode psychosis patients was of a level associated with clinical consequences in other brain disorders ( 18 , 19 ) and thus warrants clinical attention in this patient group.

The second main finding is the clear and statistically significant contribution of apathy to functional loss among first-episode psychosis patients, in line with a previous study of patients with chronic schizophrenia that also found that apathy was more strongly associated with poor functioning than other symptoms ( 30 ). The importance of apathy in relation to functioning must be seen in the light of its definition as "lack of motivation and goal-directed behavior" ( 27 ). Goal-directed behavior is one of the most important factors supporting development in a young person's life ( 46 ), and the lack of motivation is thus a core feature of negative symptoms ( 23 ).

The third main finding concerns the patient characteristics that had a significant association with apathy. Poor premorbid social functioning and the presence of disorganized symptoms were significantly related to current level of apathy, whereas diagnosis, use of antipsychotic medication, and depression were not. The clear associations of apathy with premorbid social functioning support the theory that apathy is a primary symptom linked to the neurodevelopmental origins of the disorders ( 47 ) and indicate that motivational loss may have influenced functioning even before the onset of psychotic symptoms. The relationship with disorganized symptoms adds further support to this theory because disorganization comprises different aspects of formal thought disorders often regarded as more primary in nature than delusions and hallucinations ( 48 ). The additional finding, that the level of AES-C-Apathy was independent of depression and use of antipsychotic medication, is of interest because the question of whether treatable conditions such as side effects or depression are underlying causes of lack of motivation is often difficult to evaluate in clinical situations ( 9 ). Because this was a cross-sectional study, we cannot draw any conclusions with certainty about the relative independence of apathy, depression, and use of antipsychotic medication, but our findings are supported by studies of other brain disorders that have found the same relative independence of apathy and depression ( 21 , 49 , 50 ).

The finding that the only other negative subsymptom (as measured by the PANSS) that contributed to poor functioning was flat affect is of interest for the further understanding of negative symptoms. This finding is in line with the proposed subdivision of negative symptoms into two domains, an affective flattening domain and an apathy-avolition and anhedonia domain ( 8 , 51 ).

Apathy was less diagnostically specific for schizophrenia spectrum disorders than hypothesized, given that the level of apathy appeared relatively similar among patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders and patients with first-episode affective psychosis disorders (whereas the level of apathy in the "other psychosis" group was significantly lower). Other studies have also pointed to similarities in the presence of negative symptoms in affective psychoses and schizophrenia ( 52 , 53 ). Our finding thus supports the notion that studying similar symptoms across diagnostic boundaries may help us to better understand the underlying disease mechanisms, including easier linkage to neurobiological substrates ( 54 , 55 , 56 ).

Finally, the measurement of apathy as a separate symptom rather than considering it within the broader concept of negative symptoms has several important clinical implications. Negative symptoms are often treatment refractory; they are one of the main causes for functional disability and seriously impede rehabilitation efforts. However, the current behavioral description of negative symptoms as social withdrawal does not aid in understanding how we can improve patients' functioning through focused interventions. The AES is a short and relatively simple rating scale that can help clinicians disentangle primary amotivation from treatable depression and medication side effects. Because rehabilitation is a goal-directed process actively involving the patient, amotivation and lack of goal-directed behavior appear to directly interfere with and obstruct this process. The possibility of assessing the degree of motivational loss is thus a good starting point for rehabilitative efforts, because patients with high levels of apathy will need additional support and interventions. Awareness of the problem among staff can increase the proper use of remediation techniques such as prompting and encouragement instead of critique. Motivational interviewing or other motivational techniques can be used in the treatment process and help patients with motivational problems focus on their goals and thus improve their engagement in the rehabilitation process.

The above applications are in line with recent suggestions for more specific rehabilitative efforts ( 57 , 58 , 59 ) and with a recent review on cognitive remediation, which named motivation as the critical treatment target in order to optimize outcome ( 60 ). Increased awareness of apathy's role in neuropsychiatric disorders has stimulated the search for effective treatments ( 61 ). Specific motivational and behavioral approaches have clinical applications, such as in engaging patients through discussion groups, interactive education, and homework assignments ( 61 ). Studies also indicate that apathy can be alleviated to some extent by the use of dopamine agonists, but this type of treatment is problematic to use in psychotic disorders because of the risk of increasing psychotic symptoms. Better knowledge of the biological basis of apathy in schizophrenia may aid the development of more specific pharmacological treatments.

Because this was a cross-sectional study, we cannot draw conclusions about the directions of the relationships. First-episode psychoses are relatively rare, and hence number of participants is limited. The GAF-F is a global measure and thus cannot indicate whether specific functional areas are more affected by apathy than others.

Conclusions

Apathy is a common and clinically important symptom that is present at the beginning of treatment in first-episode psychosis patients; it can be disentangled from depression and medication side effects and is significantly associated with functional loss. These findings have implications for services, given that negative symptoms have been difficult to assess in clinical settings through existing evaluation methods. Clinicians who find a high level of apathy with an individual patient need to find ways to strengthen motivation and set achievable goals. Staff and other caretakers must be informed, so that this symptom is not misinterpreted as laziness or met with criticism but instead handled in such a way to increase the patient's motivation.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by a study grant from the Psychiatric Division of the Ullevål University Hospital, the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, the Josef and Haldis Andresens Grant, and the Emil Strays Grant. Other than assessing the grant application, the funding sources had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Mueser KT, McGurk SR: Schizophrenia. Lancet 363:2063–2072, 2004Google Scholar

2. Olesen J, Baker MG, Freund T, et al: Consensus document on European brain research. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 77(suppl 1):i1–i49, 2006Google Scholar

3. McGlashan TH, Fenton WS: The positive-negative distinction in schizophrenia: review of natural history validators. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:63–72, 1992Google Scholar

4. Herbener ES, Harrow M: Are negative symptoms associated with functioning deficits in both schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia patients? A 10-year longitudinal analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:813–825, 2004Google Scholar

5. McGurk SR, Moriarty PJ, Harvey PD, et al: The longitudinal relationship of clinical symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive life in geriatric schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 42:47–55, 2000Google Scholar

6. Wyatt RJ, Henter I: Rationale for the study of early intervention. Schizophrenia Research 51:69–76, 2001Google Scholar

7. Whitty P, Clarke M, McTigue O, et al: Predictors of outcome in first-episode schizophrenia over the first 4 years of illness. Psychological Medicine 38:1141–1146, 2008Google Scholar

8. Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT Jr, et al: The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:214–219, 2006Google Scholar

9. Miller AL, Mahurin RK, Velligan DI, et al: Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: where do we go from here? Biological Psychiatry 37:691–693, 1995Google Scholar

10. Erhart SM, Marder SR, Carpenter WT: Treatment of schizophrenia negative symptoms: future prospects. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:234–237, 2006Google Scholar

11. Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS: The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:238–245, 2006Google Scholar

12. Sass H: The historical evolution of the concept of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement 7:26–31, 1989Google Scholar

13. Crow TJ: Positive and negative schizophrenic symptoms and the role of dopamine. British Journal of Psychiatry 137:383–386, 1980Google Scholar

14. Andreasen NC: Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: definition and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:784–788, 1982Google Scholar

15. Marin RS: Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 3:243–254, 1991Google Scholar

16. Stuss DT, Knight RT: Principles of Frontal Lobe Function. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002Google Scholar

17. Tekin S, Cummings JL: Frontal-subcortical neuronal circuits and clinical neuropsychiatry: an update. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 53:647–654, 2002Google Scholar

18. Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, et al: Apathy in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 49:1700–1707, 2001Google Scholar

19. Pluck GC, Brown RG: Apathy in Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 73:636–642, 2002Google Scholar

20. Paulsen JS, Ready RE, Hamilton JM, et al: Neuropsychiatric aspects of Huntington's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 71:310–314, 2001Google Scholar

21. Andersson S, Krogstad JM, Finset A: Apathy and depressed mood in aquired brain damage: relationship to lesion localization and psychophysiological reaction. Psychological Medicine 29:447–456, 1999Google Scholar

22. Kraepelin E: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Huntington, NY, Krieger, 1971Google Scholar

23. Brown RG, Pluck G: Negative symptoms: the "pathology" of motivation and goal-directed behaviour. Trends in Neurosciences 23:412–417, 2000Google Scholar

24. Foussias G, Remington G: Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: avolition and Occam's razor. Schizophrenia Bulletin Jul 21, 2008 [Epub ahead of print]Google Scholar

25. Barch DM: Emotion, motivation, and reward processing in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: what we know and where we need to go. Schizophrenia Bulletin 34:816–818, 2008Google Scholar

26. Welham J, Stedman T, Clair A: Choosing negative symptom instruments: issues of representation and redundancy. Psychiatry Research 87:47–56, 1999Google Scholar

27. Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S: Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Research 38:143–162, 1991Google Scholar

28. Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Chemerinski E, et al: Syndromic validity of apathy in Alzheimer's disease. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:872–877, 2001Google Scholar

29. Faerden A, Nesvag R, Barrett EA, et al: Assessing apathy: the use of the Apathy Evaluation Scale in first episode psychosis. European Psychiatry 23:33–39, 2008Google Scholar

30. Kiang M, Christensen BK, Remington G, et al: Apathy in schizophrenia: clinical correlates and association with functional outcome. Schizophrenia Research 63:79–88, 2001Google Scholar

31. The Frontal Lobes and Neuropsychiatric Illness. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2008Google Scholar

32. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al: Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 272:1749–1756, 1994Google Scholar

33. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261–276, 1987Google Scholar

34. Toomey R, Kremen WS, Simpson JC, et al: Revisiting the factor structure for positive and negative symptoms: evidence from a large heterogeneous group of psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:371–377, 1997Google Scholar

35. Emsley R, Rabinowitz J, Torreman M: The factor structure for the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) in recent-onset psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 61:47–57, 2003Google Scholar

36. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

37. Mueser K, Noordsy D, Drake R, et al: Integrated Treatement for Dual Disorders. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

38. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ: Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:470–484, 1982Google Scholar

39. Larsen TK, Friis S, Haahr U, et al: Premorbid adjustment in first-episode non-affective psychosis: distinct patterns of pre-onset course. British Journal of Psychiatry 185:108–115, 2004Google Scholar

40. MacBeth A, Gumley A: Premorbid adjustment, symptom development and quality of life in first episode psychosis: a systematic review and critical reappraisal. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 117:85–99, 2008Google Scholar

41. Haahr U, Friis S, Larsen TK, et al: First-episode psychosis: diagnostic stability over one and two years. Psychopathology 41:322–329, 2008Google Scholar

42. Pedersen G, Hagtvet KA, Karterud S: Generalizability studies of the Global Assessment of Functioning-Split Version. Comprehensive Psychiatry 48:88–94, 2007Google Scholar

43. Jones SH, Thornicroft G, Coffey M, et al: A brief mental health outcome scale: reliability and validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). British Journal of Psychiatry 166:654–659, 1995Google Scholar

44. Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, et al: Prevention of negative symptom psychopathologies in first-episode schizophrenia: two-year effects of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 65:634–640, 2008Google Scholar

45. Ventura J, Liberman RP, Green MF, et al: Training and quality assurance with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P). Psychiatry Research 79:163–173, 1998Google Scholar

46. Pintrich PR, Schunk DH: Motivation in Education: Theory, Research and Applications. Upper Saddle River, NJ, Merrill Prentice Hall, 2002Google Scholar

47. Hollis C: Developmental precursors of child- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia and affective psychoses: diagnostic specificity and continuity with symptom dimensions. British Journal of Psychiatry 182:37–44, 2003Google Scholar

48. Basso MR, Nasrallah HA, Olson SC, et al: Neuropsychological correlates of negative, disorganized and psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 31:99–111, 1998Google Scholar

49. Starkstein SE, Ingram L, Garau ML, et al: On the overlap between apathy and depression in dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 76:1070–1074, 2005Google Scholar

50. Kirsch-Darrow L, Fernandez HH, Marsiske M, et al: Dissociating apathy and depression in Parkinson disease. Neurology 67:33–38, 2006Google Scholar

51. Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS: The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:246–249, 2005Google Scholar

52. Galynker II, Cai J, Ongseng F, et al: Hypofrontality and negative symptoms in major depressive disorder. Journal of Nuclear Biology and Medicine 39:608–612, 1998Google Scholar

53. Lavretsky H, Ballmaier M, Pham D, et al: Neuroanatomical characteristics of geriatric apathy and depression: a magnetic resonance imaging study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 15:386–394, 2007Google Scholar

54. Roth RM, Flashman LA, Saykin AJ, et al: Apathy in schizophrenia: reduced frontal lobe volume and neuropsychological deficits. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:157–159, 2004Google Scholar

55. Apostolova LG, Akopyan GG, Partiali N, et al: Structural correlates of apathy in Alzheimer's disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 24:91–97, 2007Google Scholar

56. Andersson S, Bergedalen AM: Cognitive correlates of apathy in traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology 15:184–191, 2002Google Scholar

57. Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP: Integrating treatment with rehabilitation for persons with major mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 54:1491–1498, 2003Google Scholar

58. Velligan DI, Mueller J, Wang M, et al: Use of environmental supports among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 57:219–224, 2006Google Scholar

59. Whitehorn D, Lazier L, Kopala L: Psychosocial rehabilitation early after the onset of psychosis. Psychiatric Services 49:1135–1137, 1147, 1998Google Scholar

60. Velligan DI, Kern RS, Gold JM: Cognitive rehabilitation for schizophrenia and the putative role of motivation and expectancies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:474–485, 2006Google Scholar

61. Roth RM, Flashman LA, McAllister TW: Apathy and its treatment. Current Treatment Options in Neurology 9:363–370, 2007Google Scholar