Multifamily Psychoeducation for First-Episode Psychosis: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Family psychoeducation is recognized as part of optimal treatment for first-episode psychosis ( 1 ), and one program that has received recent attention within the first-episode literature ( 2 , 3 ) is multifamily group psychoeducation ( 4 ). This intervention has been shown to reduce the rates of relapse and hospitalization among individuals with psychotic disorders ( 5 , 6 ) and is recognized as an evidence-based treatment for psychotic disorders ( 7 ).

Unfortunately, concerns about the cost of family psychoeducation have limited the use of this intervention ( 8 ). Although available evidence suggests that family psychoeducation is cost-effective ( 6 , 9 , 10 ), most past cost-effectiveness analyses suffer from methodological limitations that hinder their utility in guiding decisions to incorporate this intervention within clinical services. For example, many past studies do not specify the metric in which their results are presented (such as 2008 U.S. dollars). Because the value of a dollar varies over time as a result of inflation, not specifying a metric leaves readers unable to estimate current costs and benefits with the results of these studies. In addition, most past studies did not control for the differential timing of costs and consequences (for example, the costs a clinic must incur in delivering family psychoeducation before obtaining the clinical benefits associated with this intervention). Drawing on the concept of "time preference" (that is, people value future costs less negatively than present costs and future benefits less positively than present benefits), cost-effectiveness guidelines suggest that dollars expended in the delivery of an intervention should be valued more than dollars saved at a later date because of the clinical benefits of the intervention ( 11 ).

Concerns about the cost of family psychoeducation are further complicated in that they are likely to be intertwined with concerns about delivering the intervention with the same clinical effectiveness as the intervention's developers. Specifically, when a new behavioral intervention is implemented, the resulting clinical benefits partly depend on the clinical skill and learning curve of the mental health professionals who deliver the intervention ( 12 ). Consequently, interventions that are cost-effective when delivered by experienced clinicians may not necessarily be cost-effective when delivered by less experienced clinicians.

Thus the goal of this study was to estimate the utility of providing multifamily group psychoeducation to individuals with first-episode psychosis and their families. First, we estimated the benefits and cost of incorporating multifamily group psychoeducation for first-episode psychosis within a mental health center after controlling for time preference. Second, we reanalyzed the data after reducing the clinical benefits of multifamily group psychoeducation to examine whether clinically less effective versions of this intervention would remain cost-effective.

Methods

Using statistical simulation and R software ( 13 , 14 ), we modeled a hypothetical mental health center serving a population of 100,000 individuals. We then examined the cost and burden of illness incurred under two scenarios—one in which usual treatment, pharmacotherapy, was provided to all individuals with first-episode psychosis who presented to the mental health center and another in which these same individuals were provided multifamily group psychoeducation in addition to usual treatment for all years in which they received treatment at the mental health center. Cost of treatment and burden of illness were assessed at four time points (two, five, ten, and 20 years). Because research shows that brief family psychoeducation programs may have limited clinical benefit ( 15 ), our model examined costs and benefits of treatment only for individuals who received at least one year of family psychoeducation.

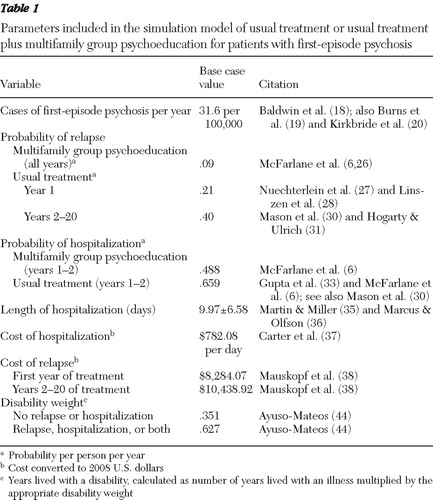

Base case model parameters are listed in Table 1 . The flow of patients through the model is depicted in a figure available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .

|

Given that yearly incidence rates of first-episode psychosis are reported to cluster between 30 and 35 per 100,000 people ( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ), we assumed a yearly incidence rate of 31.6 per 100,000 ( 18 ). Using data from Srihari and colleagues ( 3 ) as well as from the National Comorbidity Survey and the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study ( 21 ), we assumed that only 50% of these individuals would receive treatment at the mental health center. Arrival time of treatment-seeking individuals at the mental health center was modeled as a homogeneous Poisson process ( 22 ), given evidence suggesting no seasonal variation in the rate of presentation of individuals with first-episode psychosis to mental health clinics ( 23 ).

In our model a multifamily group for psychoeducation services was formed once a pool of six interested patients and their caregiving relatives was available. However, given that not all individuals who sought treatment at the mental health center would be willing or able to participate in a multifamily group, we assumed that a minimum of ten mental health center patients would be required to obtain a pool of six interested families ( 2 ).

In our model each family participating in a multifamily group is provided with three one-hour introductory "joining" sessions with a clinician and participates in an eight-hour psychoeducational workshop led by two clinicians before the start of the multifamily group meetings ( 4 ). Costs of these services were estimated with the average hourly wage of a mental health counselor reported by the 2007 National Compensation Survey ( 24 ) converted into 2008 U.S. dollars ($19.44) according to the Consumer Price Index ( 25 ). An additional two hours of time per patient was included to account for time spent completing paperwork and other preparatory activities.

During the first year in which psychoeducation is offered, our model assumes that each multifamily group would meet for 90 minutes on alternate weeks and would be staffed by two clinicians ( 4 ). For all subsequent years, the frequency of meetings would decrease to once per month. Two additional hours of staff time per meeting were included to account for time needed to complete paperwork and other preparatory activities.

The probability of relapse (specifically, a significant exacerbation of psychotic symptoms not necessarily requiring hospitalization) for the multifamily group scenario during the first year of treatment was estimated to be .09, based on data from studies by McFarlane and colleagues ( 6 , 26 )—the sole randomized controlled study of the intervention among a group comprised predominantly of individuals with recent-onset psychosis. We obtained our estimate of the probability of relapse for the first year of the usual treatment scenario (.21) from Nuechterlein and colleagues' study of recent-onset psychosis ( 27 ). The operational definitions for relapse used in both of those studies are similar, and the relapse rate in the Nuechterlein and colleagues study comports with results from another study of recent-onset psychosis that used similar operational definitions of relapse ( 28 ). Because relapse rates typically increase after the first year of illness ( 29 ), we included an assumption in our model that the probability of relapse for individuals in usual treatment was .40 for each subsequent year ( 30 , 31 ). Because the reduced rates of relapse associated with multifamily group psychoeducation can be maintained with continuous treatment ( 26 ) or because the benefits of family psychoeducation persist after termination of treatment ( 32 ), we assumed that the probability of relapse in the multifamily group scenario would remain at .09 for all years of treatment.

The probability of hospitalization in the first two years of the multifamily group scenario was assumed to be .488, which is based on the study of McFarlane and colleagues ( 6 ). The probability of hospitalization during the first two years of the usual treatment scenario (.659) was estimated with the one-year hospitalization rates (.486) from Gupta and colleagues ( 33 ) and with the ratio between the one- and two-year probability of hospitalization reported by McFarlane and colleagues (.360/.488≈.486/.659). This estimate comports with findings from other naturalistic studies of first-episode psychosis ( 30 ). Consistent with available evidence ( 30 ), we assumed that rates of hospitalization in both the usual treatment and multifamily group psychoeducation scenarios would decrease over time. Consequently, we calculated the declining probabilities of hospitalization over the course of treatment using data from Eaton and colleagues' ( 34 ) longitudinal study of hospitalization rates of over 1,000 individuals with first-episode psychosis.

Our model assumes an average length of hospitalization of 9.97±6.58 days ( 35 ). This estimate is consistent with the results of other studies ( 36 ) and is an accurate estimate of the length of both initial and subsequent hospitalizations for psychotic disorders ( 35 ). When our model predicted that a hospitalization would occur, length of stay was determined by drawing a random number from a truncated normal distribution (that is, no values were less than 1), resulting in 9.97±6.58 days. Cost of the hospitalization was calculated by multiplying the length of stay by the median daily cost for inpatient psychiatric hospitalization reported by 407 psychiatric hospitals within the United States ( 37 ) converted into 2008 U.S. dollars ($782.08 per day).

We derived our estimate of the cost of relapse using data from Mauskopf and colleagues ( 38 ). During the first year of treatment, we estimated the cost of a relapse to be the difference between the annual cost of outpatient care for an individual with a new diagnosis of schizophrenia and the annual cost of outpatient care for an individual experiencing an acute psychotic episode; estimates were converted to 2008 U.S. dollars ($8,284.07). For all subsequent years, the cost of a relapse was the difference between the annual cost of outpatient care for an individual with schizophrenia with no acute episode and the annual cost of outpatient care for an individual experiencing an acute episode, again converted to 2008 U.S. dollars ($10,438.92). To the best of our knowledge, this is the only study that has estimated how the cost of outpatient treatment in the United States varies according to the occurrence of a relapse. However, studies from other countries support the conclusion that relapses are associated with significant cost increases for outpatient care ( 39 ).

Burden of illness was quantified according to the "years lived with disability" formula (YLD) ( 40 ). YLD is calculated by multiplying the number of years lived with an illness by a disability weight for the specific illness. Traditionally, YLD is not used as an independent measure of burden of illness. Rather, the calculations are typically summed with the number of years of life lost (YLL) as a result of premature death from an illness to calculate disability-adjusted life-years (DALY). However, YLL comprises a nonsignificant amount of the burden experienced by individuals with psychotic illnesses ( 41 ), and we therefore estimated burden solely on the basis of YLD. Age weights were not used in the calculations of YLD, given the controversial nature of such adjustments ( 42 , 43 ).

Disability weights used in the calculations of YLD were obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) ( 40 , 44 ). Individuals who did not experience a relapse or hospitalization in a given year were assigned a disability weight associated with "treated schizophrenia" (.351) for that year. Individuals who experienced a relapse or hospitalization in a given year were assigned a disability weight associated with "untreated schizophrenia" (.627) for that year.

Consistent with cost-effectiveness analysis guidelines ( 11 ), all costs and consequences (such as relapses) were discounted at a rate of 3% per year to account for time preference. In addition, per WHO guidelines ( 45 ), multifamily group psychoeducation would be considered cost-effective if its cost was less than three times the 2008 U.S. gross domestic product per capita per YLD averted (that is, in 2008 U.S. dollars, <$144,000).

Because data generated by our model may not be normally distributed, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with nonparametric bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to determine statistical significance.

Results

Model diagnostics

To evaluate model diagnostics, we examined the rates of hospitalization and relapse among the members of the first multifamily group over the course of the two-, five-, ten-, and 20-year scenarios. The values were calculated for both the multifamily group psychoeducation and the usual treatment scenarios.

We calculated the number of simulations required to obtain estimates within 1% accuracy of our assumed true values for relapse and hospitalization at a 1% level of statistical significance ( 46 ). The scenarios required the following number of simulations: two years, 111,569; five years, 28,628; ten years, 12,903; and 20 years, 6,171. In addition, bias values—estimates of the accuracy of our model—for the predicted number of relapses and hospitalizations were less than one-half of the empirical standard error for each estimated variable for the two-, five-, ten-, and 20-year scenarios, suggesting that the model did not have problematic levels of bias ( 46 ).

Descriptive statistics

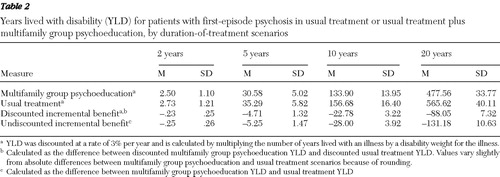

The mean±SD numbers of multifamily groups formed for the scenarios were as follows: two years, 1.02±.43; five years, 5.75±.83; ten years, 13.64± 1.23; and 20 years, 29.44±1.77. YLDs for participants in the multifamily group and usual treatment scenarios are listed in Table 2 . At each time point, YLD was greater in the usual treatment scenario than in the multifamily group psychoeducation scenario (all 95% CIs do not contain 0).

|

To estimate the clinical significance of this reduction in YLD, we used WHO data ( 40 ) to compare the number of years of disability saved through the provision of multifamily group psychoeducation during the two-year scenario with the years of disability that would be saved through the prevention of other diseases. Because our model predicted that it would take approximately one year to accumulate enough families to form the one multifamily group established during the two-year scenario, all of the clinical benefits associated with the provision of this intervention occurred during the second year of the scenario because this was the only time that the intervention was provided. The clinical benefits that occurred during this one-year period (-.23 YLD) were greater than those that would occur through the prevention of one episode of stomach cancer (-.22) or malaria (-.21 to -.17) among the six group members during this one-year period.

Cost analysis

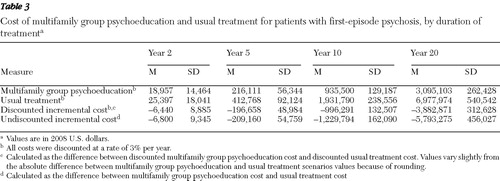

Costs for the multifamily group and usual treatment scenarios are listed in Table 3 . The total cost of the multifamily group psychoeducation scenario (cost to provide psychoeducation, plus hospitalization costs, plus relapse costs) was less than the total cost of usual treatment (hospitalization costs plus relapse costs) at years 2, 5, 10, and 20 (all 95% CIs do not contain 0).

|

Reduced-benefits scenarios

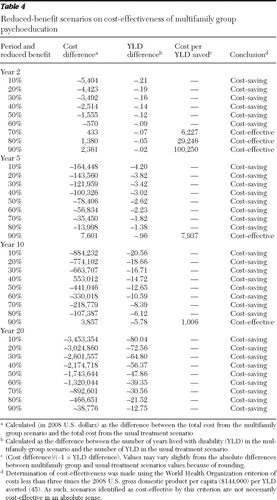

To examine whether clinically less effective versions of multifamily psychoeducation outperform usual treatment with regard to clinical benefits and costs, we reran the simulation model after reducing the benefits of the intervention with regard to relapse and hospitalization relative to usual treatment ( Table 4 ). For example, in the 50% reduced-benefits scenario, we inflated the rates of relapse and hospitalization in the multifamily group psychoeducation scenario so that the difference in the rates of relapse and hospitalization in the multifamily group scenario versus the usual treatment scenario was reduced by 50% relative to the difference in the base case values of these parameters. For each period YLD was greater in the usual treatment scenario than in the multifamily group scenario even after a 90% reduction in the clinical benefits of multifamily group psychoeducation relative to usual treatment (all 95% CIs do not contain 0).

|

To estimate the clinical significance of our results, we again compared the number of YLDs saved in the two-year scenario with the number that would be saved through the prevention of other diseases. The size of the clinical benefits that occur during the one year in which multifamily psychoeducation is provided in this scenario ranged from being equal to the prevention of an inner-ear infection (-.02; 90% reduction in clinical benefits) to being greater than the prevention of one incidence of lung cancer (-.15; 10% reduction in clinical benefits) among the six group members during this one-year period.

Multifamily group psychoeducation remained a cost-saving intervention even after a 60%, 70%, 80%, and 90% reduction in clinical benefits for the two-, five-, ten-, and 20-year scenarios, respectively. Using WHO criteria, we determined that this intervention was at least cost-effective even after a 90% reduction in clinical benefits for all time periods.

Additional sensitivity analyses

We completed additional sensitivity analyses in which we individually varied the parameters included in our base case model that were not varied in the reduced-benefits scenario analyses of incidence rate, length of hospitalization, cost of hospitalization, and cost of relapse. Specifically, we reran our base case model twice for each parameter—once where we increased the value of the parameter by 50% and once where we decreased the value of the parameter by 50%. Multifamily psychoeducation remained a cost-saving intervention in all of these scenarios.

Discussion

Our results suggest that multifamily group psychoeducation may be a cost-effective intervention for first-episode psychosis. Multifamily group psychoeducation was cost-effective in all of the investigated scenarios and was a cost-saving intervention in most of the scenarios. Moreover, our results suggest that multifamily psychoeducation programs that facilitate smaller clinical benefits than those reported in past studies may still be both cost-effective and clinically superior to usual care. Thus, even within the current negative fiscal climate, there may be both clinical and financial justification for the provision of multifamily group psychoeducation for individuals with first-episode psychosis.

This study suffers from several limitations. First, like all simulation analyses, the accuracy of our results is dependent on the quality of assumptions built into the model. Consequently, our findings should be viewed as preliminary until data from large-scale trials are available. Second, costs associated with the provision of usual treatment as well as other costs associated with psychotic disorders (such as lost productivity) were not included in our model. Third, WHO cost-effectiveness standards may not be consistent with health priorities or available economic resources in different settings. Consequently, decisions with regard to the incorporation of multifamily group psychoeducation for first-episode psychosis in specific mental health care settings may need to include consideration of local mental health priorities and available resources. Fourth, we did not examine issues related to payer mix and payment mechanism for multifamily psychoeducation within our model—two factors that may further complicate assessments of cost-effectiveness for clinical interventions. Finally, to maximize costs associated with the delivery of multifamily psychoeducation, our model assumed that no participants would drop out of treatment. However, because available evidence suggests that the rate of attrition in the usual treatment and family psychoeducation scenarios would be similar ( 47 ), multifamily group psychoeducation would likely remain cost-effective even if treatment attrition was accounted for in the model.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that when provided for two years, multifamily group psychoeducation ranges from cost-effective to cost-saving, depending on the clinical benefits facilitated by the staff delivering the intervention. However, when provided for longer durations (that is, five, ten, or 20 years), multifamily group psychoeducation was a cost-saving intervention even in scenarios assuming up to a 90% reduction in the expected clinical benefits of the intervention. Consequently, the provision of family psychoeducation for first-episode psychosis may be both clinically beneficial and cost-effective.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for this research was provided by the State of Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services and by a grant from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. International Early Psychosis Writing Group: International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 187 (suppl 48):s120–s124, 2005Google Scholar

2. Fjell A, Thorson GRB, Friis S, et al: Multifamily group treatment in a program for patients with first-episode psychosis: experience from the TIPS project. Psychiatric Services 58:171–173, 2007Google Scholar

3. Srihari VH, Woods SW, Walsh B, et al: Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis (STEP): a pragmatic randomized controlled trial in the US public sector. Schizophrenia Research 86(suppl 1):S165, 2006Google Scholar

4. McFarlane WR: Multifamily Groups in the Treatment of Severe Psychiatric Disorders. New York, Guilford Press, 2002Google Scholar

5. Dyck DG, Hendryx MS, Short RA, et al: Service use among patients with schizophrenia in psychoeducational multiple-family group treatment. Psychiatric Services 53:749–754, 2002Google Scholar

6. McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, et al: Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679–687, 1995Google Scholar

7. Evidence-Based Practices: Shaping Mental Health Services Toward Recovery. Family Psychoeducation. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/cmhs/communitysupport/toolkits/family Google Scholar

8. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903–910, 2001Google Scholar

9. Liberman RP, Cardin V, McGill CW, et al: Behavioural family management of schizophrenia: clinical outcomes and cost. Psychiatric Annals 17:610–619, 1987Google Scholar

10. Tarrier N, Lowson K, Barrowclough C: Some aspects of family interventions in schizophrenia: II. financial considerations. British Journal of Psychiatry 159:481–484, 1991Google Scholar

11. Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al: Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

12. Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH: Clinical Epidemiology: How to Do Clinical Practice Research. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005Google Scholar

13. Ross SM: Simulation. San Diego, Academic Press, 2002Google Scholar

14. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Va, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2008Google Scholar

15. Dixon L, Adams C, Lucksted A: Update on family psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:5–20, 2000Google Scholar

16. Barnett JH, Werners U, Secher SM, et al: Substance use in a population-based clinic sample of people with first-episode psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 190:515–520, 2007Google Scholar

17. Cullberg J, Levander S, Holmqvist R, et al: One-year outcome in first episode psychosis patients in the Swedish Parachute project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 106:276–285, 2002Google Scholar

18. Baldwin P, Browne D, Scully PJ, et al: Epidemiology of first-episode psychosis: illustrating challenges across diagnostic boundaries through the Cavan-Monaghan Study at 8 years. Schizophrenia Bulletin 31:624–638, 2005Google Scholar

19. Burns JK, Esterhuizen T: Poverty, inequality and the treated incidence of first-epsiode psychosis: an ecological study from south Africa. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43:331–335, 2008Google Scholar

20. Kirkbride JB, Pearon P, Morgan C, et al: Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center ÆSOP study. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:250–258, 2006Google Scholar

21. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al: The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research 36:987–1007, 2001Google Scholar

22. Kingman JFC: Poisson Processes. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 1992Google Scholar

23. Strous RD, Pollack S, Robinson D, et al: Seasonal admission patterns in first episode psychosis, chronic schizophrenia, and nonschizophrenic psychoses. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 189:642–644, 2001Google Scholar

24. National Compensation Survey: Occupational Wages in the United States, June 2007. Washington, DC, US Department of Labor, 2007Google Scholar

25. Consumer Price Index 2008. Washington, DC, US Department of Labor, 2007Google Scholar

26. McFarlane WR, Link B, Dushay R, et al: Psychoeducational multiple family groups: four-year relapse outcome in schizophrenia. Family Process 34:127–144, 1995Google Scholar

27. Nuechterlein KH, Miklowitz DJ, Ventura J, et al: Classifying episodes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: criteria for relapse and remission applied to recent-onset samples. Psychiatry Research 144:153–166, 2006Google Scholar

28. Linszen D, Dingemans P, Van Der Does JW, et al: Treatment, expressed emotion and relapse in recent onset schizophrenic disorders. Psychological Medicine 26:333–342, 1996Google Scholar

29. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, et al: Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:241–247, 1999Google Scholar

30. Mason P, Harrison G, Glazebrook C, et al: The course of schizophrenia over 13 years: a report from the International Study on Schizophrenia (ISoS) coordinated by the World Health Organization. British Journal of Psychiatry 169:580–558, 1996Google Scholar

31. Hogarty GE, Ulrich RF: The limitations of antipsychotic medication on schizophrenia relapse and adjustment and the contributions of psychosocial treatment. Journal of Psychiatric Research 32:243–250, 1998Google Scholar

32. Tarrier N, Barrowclough C, Porceddu K, et al: The Salford Family Intervention Project: relapse rates of schizophrenia at five and eight years. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:829–832, 1994Google Scholar

33. Gupta S, Andreasen NC, Arndt S, et al: The Iowa Longitudinal Study of Recent Onset Psychosis: one-year follow-up of first episode patients. Schizophrenia Research 23:1–13, 1997Google Scholar

34. Eaton WW, Bilker W, Haro JM, et al: Long-term course of hospitalization for schizophrenia: part II. change with passage of time. Schizophrenia Bulletin 18:229–241, 1992Google Scholar

35. Martin BC, Miller LS: Expenditures for treating schizophrenia: a population-based study of Georgia Medicaid recipients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:479–488, 1998Google Scholar

36. Marcus SC, Olfson M: Outpatient antipsychotic treatment and inpatient costs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 34:173–180, 2008Google Scholar

37. Carter C, Stevens M, Durkin M: Effects of risperidone therapy on the use of mental health care resources in Salt Lake County, Utah. Clinical Therapeutics 20:352–363, 1998Google Scholar

38. Mauskopf JA, David K, Grainger DL, et al: Annual health outcomes and treatment costs for schizophrenia populations. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 19):14–19, 1999Google Scholar

39. Almond S, Knapp M, Francois C, et al: Relapse in schizophrenia: clinical outcomes and quality of life. British Journal of Psychiatry 184:346–351, 2004Google Scholar

40. Murray CJL, Lopez AD: The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

41. Andrews G, Sanderson K, Corry J, et al: Cost-effectiveness of current and optimal treatment for schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 183:427–435, 2003Google Scholar

42. Anand S, Hanson K: Disability-adjusted life years: a critical review. Journal of Health Economics 16:685–702, 1997Google Scholar

43. Barendregth JJ, Bonneuz L, Van der Maas PJ: DALYs: the age-weight on balance. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 74:439–443, 1996Google Scholar

44. Ayuso-Mateos JL: Global Burden of Schizophrenia in the Year 2000: Version 1 Estimates. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2006. Available at www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bod_schizophrenia.pdf Google Scholar

45. Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development. Geneva, World Health Organization, Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, 2001Google Scholar

46. Burton A, Altman DG, Royston P, et al: The design of simulation studies in medical statistics. Statistics in Medicine 25:4279–4292, 2006Google Scholar

47. Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, et al: Family intervention for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD000088, 2006. DOI 10.1002/14651858.CD000088.pub2Google Scholar