Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Mental Disorders Among African Americans, Black Caribbeans, and Whites

According to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) "is a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered part of conventional medicine" ( 1 ). The mainstream health care system has become increasingly interested in understanding who uses CAM, in what circumstances CAM is used, and the relationship between alternative and conventional therapies. Previous research has found that 34% to 45% of the U.S. population uses some form of CAM ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ), and roughly 9% has visited a CAM practitioner ( 7 , 8 , 9 ). These studies encompassed a range of alternative therapies and practices, such as chiropractic, massage, acupuncture, megavitamins, herbal remedies, biofeedback, and hypnosis.

Adults suffering from mental and substance use disorders are often heavy users of medical services, and yet there is substantial evidence that many of these individuals receive inadequate treatment or do not use mental health services ( 10 , 11 ). In addition, there is continuing evidence that members of racial or ethnic minority groups underutilize mental health services compared with non-Hispanic whites ( 10 , 12 ). These studies have focused largely on traditional services in the general and mental health sectors. Only a handful of the studies on CAM use have focused explicitly on those with a mental disorder ( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ), and even fewer have examined racial and ethnic differences in CAM use in this vulnerable group ( 15 , 16 ).

This study used a nationally representative sample to examine the use of CAM among African Americans, black Caribbeans, and non-Hispanic whites who met diagnostic criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder. Given the lack of existing research in this area, this study took an exploratory approach. However, it built on previous research in several ways. First, it took an in-depth look at the use of CAM specifically for the treatment of a mental disorder. Second, the presence of mental disorders was assessed by using a fully structured diagnostic interview administered to a nationally representative community-based sample. This allowed for an examination of CAM use among those who may or may not have been previously diagnosed or received traditional mental health services. Finally, this is the first study that examined differences in CAM use among American blacks by comparing African Americans and black Caribbeans.

Methods

Sample

This study used data from the National Survey of American Life: Coping With Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL) ( 19 ) and the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) ( 20 ). The NCS-R and NSAL are both part of the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and are designed to be complementary data sets. Each of the CPES studies shares a set of objectives and survey instrumentation. Both studies were conducted by the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan and shared the multistage area probability sample designs common to the national surveys conducted by the Survey Research Center ( 21 , 22 ). Data were collected from 2001 to 2003 in both studies. In addition, the CPES studies were designed to allow integration of design-based analysis weights to combine data sets as though they were a single, nationally representative study ( 23 ).

At the same time, however, each survey has unique features in its national area probability samples that complement one another. The NCS-R, for example, was designed to be representative of the U.S. population in general and included face-to-face interviews with 9,282 residents of English-speaking households who were 18 years or older. The NSAL, however, was designed to be representative of blacks in the United States and was based on a national household probability sample of 6,082 African Americans, non-Hispanic whites, and blacks of Caribbean descent.

This study builds on the strengths of each survey by using a pooled sample of 631 African Americans and 245 black Caribbeans from the NSAL and 1,393 non-Hispanic whites from the NCS-R who met criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder in the past 12 months (N=2,269).

After complete description of the study to participants, informed consent was obtained. Both studies were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. The NCS-R was also approved by the Human Subjects Committee of Harvard Medical School.

Measures

Respondents in both the NCS-R and the NSAL were given a list of commonly used alternative therapies and were asked, "Did you use any of these therapies in the past 12 months for problems with your emotions or nerves or your use of alcohol or drugs?" The list of therapies included acupuncture, biofeedback, chiropractic, energy healing, exercise or movement therapy, herbal therapy (for example, St. John's wort or chamomile), megavitamins, homeopathy, hypnosis, imagery techniques, massage therapy, prayer or other spiritual practices, relaxation or meditation techniques, self-help and Internet support groups, special diets, spiritual healing by others, and any other nontraditional remedy or therapy. Dichotomous variables were created for the use of any CAM versus no use and the use of CAM only versus the use of CAM plus traditional professional services. The use of traditional service providers was assessed in the same way as the use of alternative services and included professionals from the mental health sector (psychiatrists, mental health hotlines, psychologists, and other mental health professionals), the general medical care sector (family doctors, nurses, occupational therapists, and other health professionals), and the non-health care sector (religious advisors, counselors, and social workers) ( 11 ).

Sixty-four percent of respondents who used CAM indicated using prayer or other spiritual practices, and over 50% indicated that it was the only alternative therapy used. Consistent with previous research in this area ( 3 , 24 , 25 ) we excluded those who reported using only prayer or other spiritual practices as CAM users in the multivariate analyses. Bivariate analyses are presented both with and without this category.

Past 12-month mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders for all respondents were assessed with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) ( 26 ). Mood disorders included major depression, dysthymia, and bipolar I and II disorder; anxiety disorders included panic disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia without panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder; and substance use disorders included alcohol abuse and dependence and drug abuse and dependence. A three-level rating of overall mental illness severity was determined for the 12 months before the interview (mild, moderate, or severe) ( 27 ) as well as a measure of disorder persistence (less than one year, one to four years, five to 14 years, or 15 years or more).

The main predictor of interest was race-ethnicity, which was categorized as African American, black Caribbean, and non-Hispanic white. Analyses controlled for other sociodemographic variables that have consistently been found to be related to service use. These include gender, age (18–29, 30–54, or 55 years and older), and marital status (married, never married, or previously married); socioeconomic status as measured by years of education (0–11, 12, 13–15, or 16 years or more), employment status (working or not working), and the ratio of family income to the census poverty threshold for 2001 (less than 1.5 times the poverty threshold, 1.5 to 2.9 times, 3.0 to 6.0 times, or greater than 6.0 times); and a dichotomous variable indicating whether the respondent reported having health insurance at the time of the interview.

Analysis

Rao-Scott chi square tests were used to examine differences in rates of CAM use. First, sociodemographic and mental health characteristics of respondents meeting criteria for a 12-month mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder were examined by CAM use. Then racial and ethnic differences across specific CAM therapies as well as differences in the use of traditional professional services among CAM users were examined for respondents who met criteria for any 12-month DSM-IV disorder. Finally, logistic regression models were used to test the association between use of CAM and race and ethnicity among those with a mood, anxiety, or substance disorder while controlling for other sociodemographic variables. First, separate models were examined for any CAM use (model 1), CAM use only versus CAM use with traditional professional services for the full sample (model 2), and CAM use only versus CAM use with traditional professional services for the subset of respondents who were CAM users (model 3). Then three models predicted any 12-month CAM use among respondents with a mood disorder (model 4), an anxiety disorder (model 5), or a substance use disorder (model 6). All analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.1.3, with the Taylor expansion approximation technique for calculating the complex design-based estimates of variance ( 28 ). Reporting and interpreting results focused on effect size with an alpha level of .05 as the cutoff for statistical significance in bivariate analyses and an alpha level of .001 as the cutoff for multivariate models. All analyses were weighted to yield nationally representative estimates for the groups and subgroups of interest.

Results

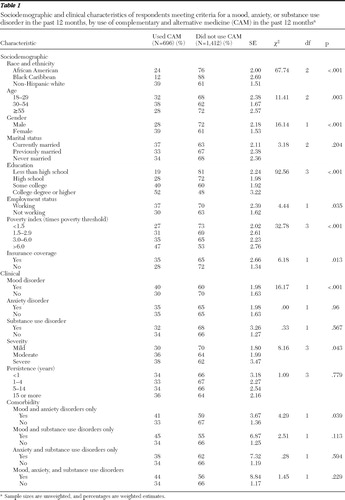

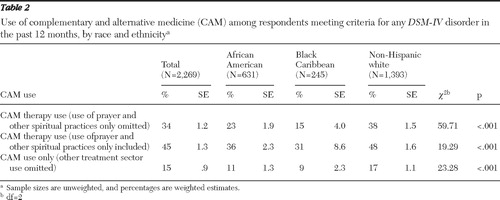

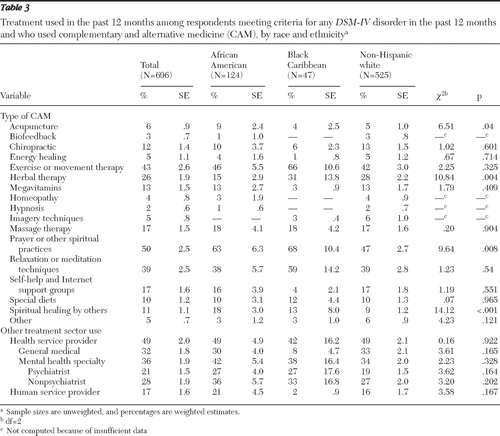

Among adults with a 12-month mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder, 34% reported using CAM in the past 12 months. A higher proportion of non-Hispanic whites (39%) used CAM for a mental or substance use disorder than either African Americans (24%) or black Caribbeans (12%) ( Table 1 ). This pattern occurred both when those who used only prayer and other spiritual practices were omitted and when they were included, as well as when the use of CAM only was examined ( Table 2 ). In the latter two instances, however, the magnitude of difference among the three groups declined. In contrast, when different CAM modalities were examined among CAM users, a smaller proportion of whites reported using prayer and other spiritual practices (47%) than African Americans (63%) and black Caribbeans (68%) ( Table 3 ).

|

|

|

In terms of other specific CAM domains ( Table 3 ), a higher proportion of African Americans (9%) reported using acupuncture than black Caribbeans (4%) and whites (5%) reported using acupuncture, although these differences were small. The use of herbal therapy was highest among black Caribbeans (31%), followed by whites (28%) and African Americans (15%). A higher proportion of African Americans reported using spiritual healing by others (18%) than either black Caribbeans (13%) or whites (9%). There were no significant racial or ethnic differences in the use of other specific CAM domains or in the use of specific traditional treatment sectors among CAM users.

Other sociodemographic characteristics were significantly related to CAM use as well ( Table 1 ). A higher proportion of adults aged 30–54 years (38%) used CAM than younger (32%) and older (28%) adults, and females were more likely than males to use CAM (39% versus 28%). The proportion using CAM increased with higher levels of education, from 19% of respondents with less than a high school education to 52% of those with a college degree or higher. A slightly higher proportion of respondents who were working at the time of the interview used CAM (37%) than those who were not working (30%). CAM use also increased with income, from 27% of those in the lowest income group to 47% of those in the highest. In addition, a somewhat higher proportion of those with insurance coverage (35%) than those without insurance (28%) reported using CAM. In terms of disorder-related variables, a higher proportion of those with a mood disorder (40%) than those without a mood disorder (30%) used CAM. The presence of an anxiety or substance use disorder was not significantly related to CAM use; however, respondents with both a mood and anxiety disorder were more likely to use CAM (41%) compared with those without these comorbid disorders (33%). The proportion who used CAM increased somewhat with overall disorder severity, from 30% among those with a mild disorder to 38% of those with a severe disorder, but the use of CAM was not related to the persistence of the disorder.

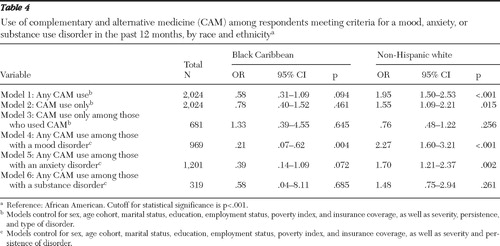

Table 4 summarizes the logistic regression models. In all of the models, an alpha of .001 was used for analyses. In model 1, whites were almost two times as likely as African Americans to report any CAM use (odds ratio [OR]=1.95). Model 2 examined CAM use only versus CAM use with traditional professional services in the full sample, and model 3 examined CAM use only versus CAM use with traditional professional services among CAM users. There were no racial or ethnic differences in either of these models at the .001 level of significance, and no differences were observed between black Caribbeans and African Americans across any of the first three models.

|

Among respondents with a 12-month mood disorder (model 4), whites were two times as likely as African Americans to use CAM (OR=2.27). Among respondents with an anxiety disorder (model 5), there were no significant differences across the three groups. In model 6, race and ethnicity were not significantly related to CAM use among respondents with substance use disorders.

Discussion

Thirty-four percent of respondents with a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder used CAM in response to their mental health problems. This is consistent with previous estimates of CAM use in the general population ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). Similarly, a study of psychiatric outpatients found that 44% used CAM to treat psychiatric symptoms ( 18 ), and a study by Unützer and colleagues ( 14 ) found that 16% to 32% of respondents with a mental disorder used CAM. These results suggest that although CAM use is a substantial source of care for adults with a mental disorder, they are not relying on CAM any more or any less than those seeking treatment for physical ailments.

More than half of those who used CAM for a mental disorder also received treatment from a traditional service provider, while 15% of the sample used CAM only. This also seems to be consistent with previous literature. Druss and Rosenheck ( 8 ) examined a sample of the adult noninstitutionalized civilian U.S. population to determine how often they visited practitioners for conventional and alternative treatment. The study found that a higher proportion used both CAM and conventional therapies (7%) than CAM alone (2%). Other studies have found that the majority of CAM users relied on both CAM and conventional mental health services ( 14 , 16 ). A previous study of psychiatric patients, however, found that only half of those using CAM therapies for psychiatric symptoms informed their doctors that they were doing so ( 18 ). Given the potential for interactions between CAM and conventional treatments, understanding how much patients reveal about CAM use to traditional service providers is an important area for further study.

Non-Hispanic whites were more likely than both African Americans and black Caribbeans to use CAM. This is consistent with previous research comparing whites and African Americans ( 3 , 5 , 9 , 15 , 25 , 29 ) and was true for overall CAM use and use of CAM only in the whole sample. The greater reliance of whites on CAM use without traditional service use raises some concern about the overall adequacy of treatment received by whites who appear to be more likely to miss the opportunity for traditional treatment. Additional analyses (not shown), however, also found that a higher proportion of CAM users (55%) than non-CAM users (30%) used traditional services. This was true for African Americans and non-Hispanic whites but not for Caribbean blacks. African Americans and non-Hispanic whites who use CAM, therefore, appear to be more likely to receive traditional treatment than those who do not use CAM. In addition, there were no racial or ethnic differences in the use of CAM only compared with use of CAM along with other treatments. Taken together, these findings suggest that CAM users tend to be service users in general and that there is no racial or ethnic difference in the tendency to substitute CAM for more conventional services.

There was no racial or ethnic difference in CAM use among those with a substance use disorder. This may be due to different overall help-seeking patterns among individuals with substance use disorders or perceptions that CAM therapies are less effective for treating substance use disorders. In addition, although overall there were few differences between African Americans and black Caribbeans, a higher proportion of black Caribbeans than African Americans reported using herbal therapies. The higher rate of herbal therapy among black Caribbeans is consistent with research indicating the long history of traditional use of medicinal herbs among Caribbeans ( 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ).

Both African Americans and black Caribbeans were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to utilize prayer and other spiritual practices, as well as spiritual healing by others. Previous research on CAM has also found that African Americans were more likely than whites to use prayer ( 3 , 24 , 25 ). This finding is also consistent with recent research using the NSAL that found that compared with non-Hispanic whites, African Americans and black Caribbeans are more religious ( 34 ) and more likely to utilize religious coping in general ( 35 ).

Overall these findings suggest that although there are differences between blacks and whites in CAM use, there are also differences among black Americans that should be considered and may be rooted in ethnic cultural differences. Because CAM therapies emerge from a variety of different cultures, it is particularly important to understand the ways in which various cultural groups incorporate CAM into more traditional treatment systems. Although this study focused specifically on black Americans, further examination of the use of CAM across Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian or Alaska Native groups is important for future studies.

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. First, the WMH-CIDI questions used to assess alcohol and drug dependence were modified such that respondents who did not report lifetime abuse symptoms were not administered questions assessing dependence. Thus individuals who have a history of dependence without abuse were excluded, resulting in underestimation of the overall rates of substance dependence ( 36 ). As suggested by Cottler ( 37 ), persons from racial or ethnic minority groups are most likely to be excluded from the data. Therefore, much like other studies involving the WMH-CIDI with this skip pattern, the results of this study should be interpreted in the context of this diagnostic issue.

Second, the number of cases was too small for multivariate analyses related to the use of specific CAM domains. This limited our ability to tease out racial and ethnic differences in this area. In addition, given the variety of CAM modalities, it may be more advantageous for future research to examine individual or smaller homogeneous groups of treatments rather than grouping all types of alternative treatments under one construct. Finally, although this study characterized results in terms of effect size, it is important to note that some of the statistically significant findings may be a result of multiple comparisons.

Conclusions

This initial study of CAM use for mental and substance use disorders among African Americans, black Caribbeans, and non-Hispanic whites identified the prevalence and types of CAM use and found both commonalities and differences across race and ethnicity in the use and types of CAM. These findings point to the need for continued study of the use of CAM for mental and substance use disorders in these groups. Given the paucity of information on African Americans and black Caribbeans on these topics, the findings further indicate the importance of investigating ethnic differences in CAM use overall and in conjunction with physical and mental health service utilization patterns within the black population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by grant U01-MH57716 from the National Institute of Mental Health, with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research, National Institutes of Health; from the University of Michigan; by grants R01-AG18782 and P30-AG15281 from the National Institute on Aging; and from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. CAM Basics: What Is CAM? Bethesda, Md, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Available at nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/D347.pdf Google Scholar

2. Astin JA: Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA 279:1548–1553, 1998Google Scholar

3. Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, et al: Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. Journal of the National Medical Association 97:535–545, 2005Google Scholar

4. Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, et al: Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): a national probability survey of CAM utilizers. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 9:50–56, 2003Google Scholar

5. Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, et al: Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997–2002. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 11:42–49, 2005Google Scholar

6. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Van Rompay MI, et al: Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: results from a national survey. Annals of Internal Medicine 135:344–351, 2001Google Scholar

7. Paramore LC: Use of alternative therapies: estimates from the 1994 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation National Access to Care Survey. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 13:83–89, 1997Google Scholar

8. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services. JAMA 282:651–656, 1999Google Scholar

9. Bausell RB, Lee W-L, Berman BM: Demographic and health-related correlates of visits to complementary and alternative medical providers. Medical Care 39:190–196, 2001Google Scholar

10. Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, et al: Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:485–494, 2007Google Scholar

11. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

12. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, et al: Mental health service utilization by African Americans and whites: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-Up. Medical Care 37:1034–1045, 1999Google Scholar

13. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Use of practitioner-based complementary therapies by persons reporting mental conditions in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:708–714, 2000Google Scholar

14. Unützer J, Klap R, Sturm R, et al: Mental disorders and the use of alternative medicine: results from a national study. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1851–1857, 2000Google Scholar

15. Wu P, Fuller C, Liu X, et al: Use of complementary and alternative medicine among women with depression: results of a national survey. Psychiatric Services 58:349–356, 2007Google Scholar

16. Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF, et al: Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 135:262–268, 2001Google Scholar

17. Wang J, Patten SB, Russell ML: Alternative medicine use by individuals with major depression. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 46:528–533, 2001Google Scholar

18. Knaudt PR, Connor KM, Weisler RH, et al: Alternative therapy use by psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:692–695, 1999Google Scholar

19. Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, et al: The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic, and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:196–207, 2004Google Scholar

20. Kessler RC, Merikangas KR: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:60–68, 2004Google Scholar

21. Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, et al: Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:221–240, 2004Google Scholar

22. Pennell B-E, Bowers A, Carr D, et al: The development and implementation of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:241–269, 2004Google Scholar

23. Heeringa S, Berglund P: Weighting: National Institutes of Mental Health Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Survey Program Data Set: Integrated Weights and Sampling Error Codes for Design-Based Analysis. Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Survey, 2007. Available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/cpes/using.xml?Section=Weighting Google Scholar

24. Grzywacz JG, Suerken CK, Neiberg RH, et al: Age, ethnicity, and use of complementary and alternative medicine in health self-management. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48:84–98, 2007Google Scholar

25. Kronenberg F, Cushman LF, Wade CM, et al: Race/ethnicity and women's use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: results of a national study. American Journal of Public Health 96:1235–1242, 2006Google Scholar

26. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al: The prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581–2590, 2004Google Scholar

27. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:593–602, 2005Google Scholar

28. SAS I: SAS/STAT User's Guide Version 9.1. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2005Google Scholar

29. Blair YA, Gold EB, Greendale GA, et al: Ethnic differences in use of complementary and alternative medicine at midlife: longitudinal results from SWAN participants. American Journal of Public Health 92:1832–1840, 2002Google Scholar

30. Gardner JM, Grant D, Hutchinson S, et al: The use of herbal teas and remedies in Jamaica. West Indian Medicine Journal 49:331–336, 2000Google Scholar

31. Michie CA: The use of herbal remedies in Jamaica. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics 12:31–36, 1992Google Scholar

32. Mahabir D, Gulliford MC: Use of medicinal plants for diabetes in Trinidad and Tobago. Pan American Journal of Public Health 1:174–179, 1997Google Scholar

33. Clement YN, Williams AF, Aranda D, et al: Medicinal herb use among asthmatic patients attending a specialty care facility in Trinidad. BMC Complementary and Altenative Medicine 5:3, 2005Google Scholar

34. Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jackson JS: Religious and spiritual involvement among older African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 62B:S238–S250, 2007Google Scholar

35. Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS, et al: Religious coping among African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites. Journal of Community Psychology 36:371–386, 2008Google Scholar

36. Kessler RC, Merikangas KR: Drug use disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey: have we come a long way? [Reply to letter.] Archives of General Psychiatry 64:381–382, 2007Google Scholar

37. Cottler LB: Drug use disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey: have we come a long way? [Letter.] Archives of General Psychiatry 64:380–381, 2007Google Scholar