Mental Health Policy Development in the States: The Piecemeal Nature of Transformational Change

In recent years the idea of transformation has been a pervasive theme in discussions of mental health policy in the United States. This broad concept encompasses a range of sweeping changes across the mental health system intended to enable individuals with serious mental illness "to live, work, learn, and participate fully in their communities" ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). The call for transformation was articulated in the final report of the 2002–2003 President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, which identified fundamental shortcomings in the current mental health system and set out comprehensive goals for system improvement ( 2 , 3 ). As defined by the Commission and ensuing reports, a transformed system is one that addresses stigma and awareness; promotes consumerism and family-driven care; eliminates disparities; facilitates screening, assessment, and referral; improves quality; and advances technology. [An appendix showing more information about the goals and recommendations listed in the Commission report is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] Further, the steps to achieve these goals are described as "complex, revolutionary, … fundamental system change" ( 4 ) that go beyond "mere reforms to the existing mental health system" ( 5 ). Thus transformation in mental health implies not only particular goals but also particular processes to achieve those ends.

As the traditional hub of mental health services administration, financing, and delivery, state mental health systems are a fundamental component—the "center of gravity" ( 5 )—of national mental health transformation plans. For example, states are well suited to address fragmentation in service delivery and financing, implement wraparound services, and conduct outreach to underserved populations. State efforts also could be crucial in developing stewardship in mental health policy. Specifically, states can elevate responsibility for mental health policy to a level above the traditional mental health authority (for example, to the office of the governor). These efforts could coordinate various bureaucracies, engage a wider array of service providers, and channel resources to agencies and institutions beyond the traditional reach of the system. Many federal transformation efforts have focused on developing state initiatives—to that end, nine states were awarded State Incentive Grants (SIGs) to develop infrastructure ( 6 )—and states also are taking it upon themselves to reform their systems by using existing or new state funds.

However, it is not clear how the vision of transformation will be balanced against traditional forces in state policy making. Transformative change is envisioned as wholesale redesign that requires systematic, coordinated effort. The process is characterized by clear vision, leadership, large-scale alignment, cultural change, and continuous feedback processes ( 4 ). In contrast, policy priorities of states may be idiosyncratic and generated by subjective political processes rather than by linear, rational ones ( 7 ). For example, researchers have demonstrated that state policy is guided by party dynamics and competition for votes, ideology and public opinion, interest group influence, and institutional structure ( 8 , 9 , 10 ). As such, policy development frequently follows a seemingly chaotic, fluid process that varies by the politics of a given issue ( 11 , 12 ). Further, this process is particular to each state's institutional structure, culture, and resources ( 13 , 14 ).

Experts in mental health policy have observed that politics have shaped policy development in the past ( 15 , 16 ). Others have noted that prior calls for fundamentally overhauling the mental health system have served more as a blueprint for incremental change than as an impetus to system reinvention ( 17 ). The study reported here analyzed state mental health policy development in four states—California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New Mexico. It relied on qualitative data on recent state mental health policy priorities collected from interviews with mental health policy makers, advocates, and providers. Drawing on the idea that state policy development may be driven by nationwide policy goals or by state-specific political factors (or both), the study used an open-ended approach to examine what issues states address and what actors or strategies drive these agendas. The analysis assessed whether and how these policy priorities versus other forces in the states reflect the broader context of transformation.

Methods

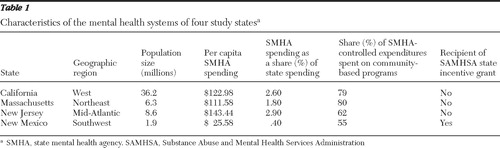

The study used qualitative evidence collected from semistructured interviews with participants in the four states. The states in the study were selected to capture variation in geography and population, spending and health systems, and political structure and environment ( 18 , 19 ) ( Table 1 ). In addition, they vary in structure and financing of their mental health systems—for example, centralized statewide coordination in New Mexico versus decentralized county administration in California—as well as in spending on mental health activities and administration. Only one of the study states (New Mexico) has received a federal SIG, just as only about one in five states has received one.

|

Interviewees in each state included key mental health officials, directors of principal mental health consumer and family advocacy groups, and executives of major mental health provider groups. Participants were recruited through a combination of purposive and snowball sampling, first by identifying individuals who held top positions in the relevant organizations and then through an iterative referral process to capture anyone else who played a central role in recent policy debates. The majority (74%) of individuals contacted (N=39 of 53) agreed to participate. Because of scheduling difficulties, the final participation rate was 66% (N=35). Participants were divided evenly between stakeholder groups and had extensive experience in state mental health policy (average experience of more than 12 years). All interviewees were guaranteed that their comments would remain anonymous and would be identified only by state and stakeholder perspective. Before each interview, consent to participate was obtained after the purpose, design, and use of the study was fully explained.

Interviews followed a semistructured protocol that covered recent mental health policy priorities in the state. Policy priorities discussed were raised by interviewees and were not restricted to those connected to transformation; this open-ended approach allowed for the possibility that state policy development was driven by transformation or other factors. Specific interview topics included respondents' descriptions of the origin, debate, and resolution of leading recent mental health policy priorities in their state; their various strategies for engaging in the debate; and their involvement with other actors on the issue. Topics also included whether and how the events and circumstances interviewees described were typical or atypical of mental health debates in their state. Interviews were conducted between May 2007 and March 2008.

Interviews were analyzed with a multistep, open-ended approach to enable themes to emerge from the data ( 20 , 21 , 22 ). First, each interview was summarized to draw out main concepts regarding what issues states prioritize and what factors drove those priorities. In this step, conceptual codes were generated from the interview results (versus a predetermined list of concepts related to transformation) to allow for development of unexpected topics. Next, similar concepts from different interviews were grouped into categories to develop themes. Each theme was developed to refine inclusion and exclusion criteria, reconcile or understand conflicting ideas, and compare nuances across states and stakeholders. Finally, the themes themselves were analyzed to examine to what extent they reflect the stated goals and processes of transformation.

Results

Recent mental health priorities in study states

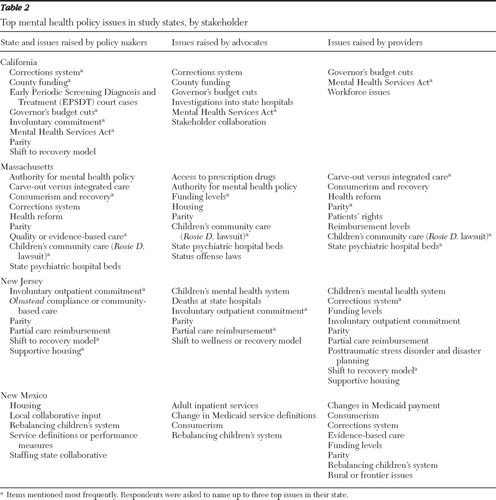

When posed the open-ended question of what issues were top mental health policy priorities in their state, participants raised a range of issues ( Table 2 ). Interpreted in light of the context of transformation, several observations stand out regarding these priorities. First, some respondents mentioned general system priorities that echoed the overall goals of transformation, such as "consumerism and recovery," "reforming the corrections system," "housing," or "employment." These priorities were more likely to be raised by policy makers than by advocates or providers, a logical finding given that state policy makers interviewed were generally in senior-level positions, which would lead them to focus on a range of issues and broad system goals. State policy priorities were also primarily related to direct service provision. That is, many concentrated on improving services for persons already in the system rather than population-based initiatives (for example, decreasing stigma or improving detection). Thus not all issues outlined in the Commission report appeared in the state policy priorities mentioned by participants.

|

Second, state policy priorities demonstrate that different states focus on different issues. Aside from the issue of payment and funding levels for service providers, no single issue was a priority across the study states. In California many respondents spoke of issues related to homelessness; in Massachusetts the emphasis was on children's community-based services; in New Jersey housing was a top issue; and in New Mexico fragmentation in financing was a leading agenda item. Each of these issues is related to one of the problems and goals outlined in the Commission report. The variation across states indicated that states are working on a limited number of issues at a time, which may lead over time to a general transformation, rather than adopting the broad, systemwide agenda implied by a transformative process.

Not only do specific issues on state mental health policy agendas vary across states, but they also materialize in ways particular to state circumstances. For example, in California, much attention on homelessness resulted from implementing the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA), a referendum-based initiative that received funding from a "millionaire tax" passed to finance expansion and transformation of county-based mental health programs. In Massachusetts focus on community-based services stemmed from the decision in the Rosie D. v. Romney case (a class-action lawsuit that called for the expansion of state community-based mental health services for children). Some state-specific priorities, such as proposed cuts to state mental health spending in California and the development of a new state inpatient hospital in Massachusetts, were unique to the state. These examples demonstrate that much of state mental health policy is specific to state circumstances and reactive.

Forces behind state mental health policy priorities

The case studies show that recent state mental health policy is largely driven by executive agendas, broad stakeholder involvement, and crisis and opportunity. Analyzing whether the underlying process generating state policy priorities is led by the ideals of transformation leads to mixed conclusions. In some ways, the process shows leadership, inclusiveness, and planning indicative of transformation, whereas in others, it reveals the politics of power, group dynamics, and opportunism.

Executive agendas. Respondents in several states indicated that recent state mental health priorities were dictated by the agenda of the administration in power. Interviewees cited several examples of new policy initiatives being "driven" or "pushed through" by governors upon entering office, regardless of whether the political party changed. For example, advocates in Massachusetts linked both increased attention to implementing the decision in the Rosie D. case and the development of a new state psychiatric hospital to a change in governor. Similarly, a provider in New Jersey noted that a governor's negative position on hospital-based care "permeated the administration" and led to an overall focus on shifting services away from inpatient providers.

Some comments from respondents show that executive direction of mental health policy reflects needed leadership and stewardship for policy change. Most notably, interviewees in New Jersey explained that one governor's ability to drive housing policy reflected his personal dedication to the issue, strong reputation as a policy expert, and political capital. As one respondent summarized, "he was very clear that mental health was his priority issue … and he wielded a lot of power, so that won the day." Many believed that governors were default leaders in mental health policy development because of the powers endowed by the office, such as control of the budget and the power to appoint mental health commissioners. For example, participants noted that governors' budgets "set the tone for what's going to happen" in mental health policy, and they explained that mental health agency actions were "driven by the fact that the Governor said you will do it and you will do it on this date … we had our marching orders." Not surprisingly, many noted the importance of gubernatorial leadership in moving forward on policies that had been "stuck" for many years, remarking that when "mental health is too far down the ladder [that is, not one of the governor's priorities], it's just kind of the stepchild." Policy makers described remarkable infusion of attention to an issue once the governor took it up, with one commenting that working on the governor's priority was "carte blanche in state government. All my phone calls got returned. Every piece of information I wanted, I got. Hell, they'd come pick me up if I asked them to."

In other ways, however, respondents' comments regarding executive leadership showed a process in conflict with a transformative one. Most notably, many mentioned that gubernatorial control led to "stop-start" policy development, as initiatives were dropped as state priorities when the governor associated with them left office. As one advocate explained, "Every time we change governors, [the new governors] say, 'I can use that money for something else; it's not my initiative.'" Others commented that policy development was dependent on the interests and priorities of the person in office. For example, one policy maker explained that he did not take up a particular issue simply because "We work for the Governor; we can't take a position that's counter [to] the Governor's position." In at least one case, conflict between the governor's personal interests and the mental health community led to conflicting priorities, as the "commissioner ran circles around the governor" and pushed a separate agenda in the legislature.

Broad stakeholder involvement. At the same time that state priorities are driven in a "top-down" manner by the administration, interviewees in each state also reported that policy was generated through a "bottom-up" process of active participation by advocates and providers at the ground level. As one policy maker summarized, state mental health policy "is a participatory sport: everyone weighs in." Respondents cited numerous examples of stakeholders driving policy. For example, policy makers in Massachusetts and New Jersey attributed the shift to a recovery model in state mental health policy to dissatisfied consumers, families, and providers and the "concerns of the larger mental health community." Similarly, participants in California described the "whatever it takes" (for recovery) approach of the MHSA as emanating from the community mental health system.

The broad stakeholder involvement described by respondents reflects several core principles of transformation, such as consumer inclusion, alignment and coordination, and cultural change. Many noted that open input into the policy process was essential to consensus building, with one advocate commenting that in contrast to simply "being polite to each other" as in the past, stakeholders were actively collaborating as a result of increased contact and interaction. Interviewees believed consensus was essential to "provide muscle" for a policy preference, create a clear direction for policy, and win funding. Others commented on the very practical need to gain the cooperation of ground-level actors who implement policies and deliver services. For example, one provider agency in New Mexico indicated that it automatically held a "seat at the table" in formulating the state's policy priorities because it served a majority of clients in its region of the state.

Importantly, in some cases stakeholder input into the policy process reflected an underlying systemic change indicative of transformation, specifically the development of infrastructure to facilitate consensus building. New Mexico's recently established centralized interagency Behavioral Health Collaborative appears to enhance access for stakeholders in the state ( 23 , 24 ). Several interviewees mentioned that, although there are still glitches, the collaborative has created a consistent mechanism to bring their views into policy making. Similarly, in California, the structure surrounding MHSA implementation has formalized stakeholder feedback, leading one advocate to comment that it is "instrumental in democratizing input" into the system. Participants in Massachusetts uniformly reported that a dedicated legislative committee on mental health and substance abuse is instrumental in providing a forum for stakeholders to raise issues, or as one participant said, "a place and a voice for advocacy for mental health services and issues."

However, analysis of comments also indicates that stakeholder involvement is not necessarily in concert with a transformed system. Many spoke of concerns about the process. Providers in New Jersey and New Mexico indicated that although they have a seat at planning meetings, "The concern is that some of them may be sort of token … maybe some of the decisions either have already been made or are being made by individuals as we go, without really taking seriously the participation of whoever is involved." Others remarked that although inclusion was generally a positive force in policy making, sometimes it can skew policy making. For example, interviewees said that "there are many self-appointed advocates that don't represent all opinions," and some participants remarked that newly included actors sometimes have a "disregard for the value of those who have been in the system for a career." A policy maker observed, "We've brought providers and consumers to the table. We just haven't given them any factual basis on which to make decisions, so they're mostly made anecdotally." In addition, several examples indicated ways in which broad-based involvement slowed progress toward policy goals, particularly in cases where consensus was difficult to achieve or stakeholders were unfamiliar with the issues. A provider explained resistance to take up the issue of housing: "We didn't have the expertise; we didn't have the confidence. Most of us went to school to be social workers and provide treatment and work in mental health; we didn't go to school to get into housing, so to speak."

Crisis and opportunity. In many cases mental health policy development in the study states was driven by unanticipated crises or opportunities that led to a new issue taking over attention. These situations arose in varied ways, from an unexpected reimbursement change by a managed care company to an unpredictable change in state leadership. Several state policy makers remarked that these critical moments occur more commonly than the few examples given in this study; as one stated, "Frankly, I've been doing this in a lot of states for a long time, and it's not unusual for a state to have either a crisis or an opportunity, and you have to do something fast."

Many participants noted that these occasions led to quick, significant shifts in policy direction. In New Jersey, where a "dramatic stroke of luck" led a supporter of mental health issues to simultaneously—and temporarily—hold the positions of Governor and Senate President, policy makers fit their efforts into a limited time frame. One respondent explained, "The time pressure was helpful in that it forced us to work hard. … Nothing focuses the mind like the hangman's noose." Similarly, when New Mexico faced a crisis in response to a payment change by a managed care company, a state policy maker said, "We had to turn the public opinion very fast or there was the risk that people would become entrenched [in the old policy perspective]."

Despite the unexpected nature of these critical moments, the interviewees indicated that strategic planning is frequently involved. Many interviewees described situations in which issues had been quietly developed for quite some time before finally emerging as state priorities during a crisis. A state policy maker in California stressed that ten years of working groups and consensus building preceded a significant mental health initiative in the state, despite the fact that the policy change appeared to occur quickly. One advocate in Massachusetts similarly explained the rapid emergence of the state hospital issue by noting, "Everybody had done all the right things up to that point, and all you needed was [the election] to connect the last dot." Another spoke more broadly: "There's a lot of preparation and coalition building that allows those giant leaps forward." Thus, although "crisis-driven policy" implies a haphazard process, the case studies show that these policy changes can in fact involve directional, coordinated effort.

Further, in all four states, interviewees described occasions in which stakeholders deliberately created opportunities. Most commonly, this was done through lawsuits against the state. Almost unanimously, respondents explained that these actions arose as a result of a feeling of being "stuck" and not having other options available to change policy. For example, participants in Massachusetts explained that before the decision in the Rosie D. class-action lawsuit, the issue of community programs for children had lingered for years, confined to small pilot programs. As one advocate stated, "There was no way that [the state] was going to make systemic universal change for at least this group of kids unless there was litigation." State policy makers concurred that lawsuits can break policy stalemates, noting that they address the fact that "states are very thick bureaucracies" that are hard to change. Another motivation behind lawsuits is to force funding, which was expressed by one interviewee who said, "One of the best ways to increase the budget is to get sued."

Of course, there is much about crisis and opportunity in state health policy that is at odds with the concept of transformation. Crises can divert attention from long-range planning as the state addresses immediate issues that incapacitate the system or create overwhelming public image problems. As one respondent summarized, "They [the agencies] are doing immediate, operational kinds of planning because they are faced with crises all of the time. … They work very, very hard, and they have to jump from thing to thing just to manage." In addition, regardless of planning and preparation before a crisis, these events can have very uncertain outcomes. Both advocates and policy makers commented that lawsuits often lead to unintended consequences, such as a focus on quantity of services over quality and content.

Discussion

There are limits to this study's ability to fully assess transformation in state mental health systems. Interviews did not cover all aspects of mental health policy in a state, and it is possible that transformation is reflected in issues other than the top priorities raised by interviewees. For the policy issues that participants did raise, this study enables only examination of whether and how their policy development reflects "transformative change" as outlined in national reports. It does not provide a causal test to confirm whether or not transformation goals shaped these priorities or processes, and it cannot definitely confirm the direction of any association (for example, whether state policy priorities were derived from the Commission report or whether state policy priorities served as a catalyst for federal actions). Rather, the study provides insight into overlap between the national transformation agenda and state mental health policy.

Several additional limitations should be noted in interpreting the results. The experiences of this small sample are not necessarily representative of all states' approaches to mental health policy change. Chosen to capture diversity in the political and organizational environment for mental health policy, these four states differ in some ways from the "average" state. Further, the findings are based on self-reported comments from stakeholders, whose statements may not necessarily reflect the full picture in the state. Respondents may have felt the need to report "acceptable" answers or present their state in a positive light, which could have resulted in findings that depict a more cohesive, inclusive process than actually occurs. Last, the breadth of the topic and the limited period covered by the interviews may have prevented nuances from emerging. Despite these limitations, the study led to a rich collection of examples and commentary from actors directly involved in the day-to-day development of state mental health policy.

The four states in this study show that many recent state policy priorities in mental health are consistent with the goals of transformation. These priorities include some big picture issues as laid out in the Commission report (such as consumerism and recovery) but more frequently involve small detail issues that vary by state (such as changes in payment rates or development of new housing options). Further, not all state efforts in mental health are related to general plans for transformation. This finding indicates that rather than revolutionary change implied by transformation, state actions are in line with piecemeal changes toward a transformed system. Transformation may provide vision and direction for policy that over time may cumulate in achieving the goals outlined in the report; however, the study states show that that end is unlikely to be achieved through wholesale change.

Nonetheless, piecemeal changes may also represent transformation if they are part of systemic or directional steps toward a larger goal. The study found mixed evidence on whether the drivers of state priorities reflected such an underlying process. The case studies showed that state policy priorities are largely shaped by executive control, stakeholder interests, and crises. Interviews and analyses revealed some ways in which these forces do not represent systemic efforts toward a transformed system. For example, state policy may be formed through short-term efforts driven by a governor's particular interests and power, group involvement may be largely symbolic, and some actions are opportunistic responses to a particular, unpredicted crisis.

On the other hand, piecemeal changes driven by leadership, grassroots pressure, or events may represent a step in the direction of systemic transformation. Transformation calls for strong leadership and an engaged network of stakeholders to promote alignment and cultural change ( 25 ). Leadership from state governors may be appropriate, given the need to address fragmentation across state systems. Further, generation of state mental health priorities through grassroots organizations is pivotal for a system aiming to embrace consumerism and responsiveness, so the strong role for stakeholders in guiding state priorities demonstrated in this study may represent a fitting marriage of politics and transformation as drivers of state policy. Last, crises can facilitate important shifts in policy, and state actors are taking advantage of these opportunities to shift the direction of policy.

Conclusions

As a whole, the findings from these four states indicate that the concept of transformation can be an important component of state mental health policy, but expectations about how transformation will play out at the state level might need to be tempered. States are largely guided by their own problems and resources: sometimes these forces dovetail with nationwide transformation goals and processes, and sometimes they are idiosyncratic to a particular state. Thus, although states can play an integral role in forwarding transformation, their own mental health policy agendas are not eclipsed by this nationwide movement.

The results lead to the question of the appropriate state and federal roles and responsibilities in transformation. As in other policy areas, states may be "laboratories of democracy" in developing innovations or initiatives toward transformation, but it is not clear whether these efforts will directly influence or be affected by a nationwide reform platform. This and other research has shown how states can be "specialized political markets in which individuals and groups develop and promote innovative products" ( 13 ). Thus the federal government may need to take a stronger role in directing nationwide transformation efforts. Analysis shows that federal direction has been helpful (as in the case of supporting New Mexico's ability to develop infrastructure to facilitate inclusion of a broad range of stakeholders) but not necessary (as in the case of other states' ability to do the same) to transformative efforts. Future federal efforts might be effective by providing more powerful incentives and resources to states to move aggressively toward a transformed system. At the same time, these efforts will be best served by acknowledging how "cooperative federalism" of federal leadership combined with room for state innovation and specification ( 26 ) can allow states to design agendas in line with their own interests.

Future research should continue to investigate the role of states in mental health transformation. Comprehensive study of changes in mental health policy across states can provide a more complete picture of the extent to which transformation is occurring. Similarly, ongoing investigation over time can determine whether early state efforts are fleeting trends or whether they build momentum toward long-term system change. Direct assessment of whether and how state policy makers acquire, interpret, and apply national policy statements such as the Commission report would be a valuable addition to the literature; such research would move understanding beyond correlation between national policy statements and state actions to direct links between the two. Similarly, investigation into how the federal transformation agenda was shaped by state actions would lead to better understanding of the role of national consensus statements such as the Commission report in moving to true system change.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The author received financial support from grant 5T32MH019733 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The author is grateful to all the study participants for sharing their time and insight. Special thanks to Howard Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., Judith Lave, Ph.D., Julie Donohue, Ph.D., Richard Frank, Ph.D., Robert Blendon, Sc.D., Ellen Meara, Ph.D., Erin Strumpf, Ph.D., Jessica Mittler, Ph.D., and Betty Downes, Ph.D., for help and advice throughout the project.

The author reports no competing interests.

1. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

2. Hogan MF: The President's New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatric Services 54:1467–1474, 2003Google Scholar

3. Iglehart JK: The mental health maze and the call for transformation. New England Journal of Medicine 350:507–514, 2004Google Scholar

4. Transformation: A Strategy for Reform of Organizations and Systems. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005. Available at www.samhsa.gov/Matrix/MHST_printable.pdf Google Scholar

5. Transforming Mental Health Care in America: The Federal Action Agenda: First Steps. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006. Available at www.samhsa.gov/Federalactionagenda/NFC_execsum.aspx Google Scholar

6. Transforming state mental health systems. SAMHSA News 14(1):12–13, 2006Google Scholar

7. Brace P, Jewett A: The state of state politics research. Political Research Quarterly 48:643–681, 1995Google Scholar

8. Sharkansky I, Hofferbert RI: Dimensions of state politics, economics, and public policy. American Political Science Review 63:867–879, 1969Google Scholar

9. Erikson, RS, Wright GC, McIver JP: Political parties, public opinion, and state policy in the United States. American Political Science Review 82:743, 1989Google Scholar

10. Jacoby WG, Schneider SK: Variability in state policy priorities: an empirical analysis. Journal of Politics 63:544–568, 2001Google Scholar

11. Kingdon JW: Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd ed. New York, HarperCollins, 1995Google Scholar

12. Baumgartner FR, Jones BD: Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1993Google Scholar

13. Oliver TR, Paul-Shaheen P: Translating ideas into actions: entrepreneurial leadership in state health care reforms. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 22:721–788, 1997Google Scholar

14. Sparer MS, Brown LD: States and the health care crisis: the limits and lessons of laboratory federalism; in Health Policy, Federalism, and the American States. Edited by Rich RF, White WD. Washington, DC, Urban Institute Press, 1996Google Scholar

15. Grob G: Government and mental health policy. Milbank Quarterly 72:471–500, 1994Google Scholar

16. Mechanic D: Establishing mental health priorities. Milbank Quarterly 72:501–514, 1994Google Scholar

17. Grob GN, Goldman HH: The Dilemma of Federal Mental Health Policy: Radical Reform or Incremental Change? New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 2006Google Scholar

18. State Health Facts Online. Total Number of Residents, States (2006–2007). Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2006–2007. Available at www.statehealthfacts.org Google Scholar

19. State Mental Health Agency Profiles Systems (Profiles) Revenues Expenditure Study. Alexandria, Va, NASMHPD Research Institute, 2006. Available at www.nri-inc.org/projects/Profiles/RevenuesExpenditures.cfm Google Scholar

20. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ: Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research 42:1758–1772, 2007Google Scholar

21. Rubin HJ, Rubin IS: Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2005Google Scholar

22. Kvale S: Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1996Google Scholar

23. Willging CE, Semansky RM: Another chance to do it right: redesigning public behavioral health care in New Mexico. Psychiatric Services 55:974–976, 2004Google Scholar

24. Willging CE, Tremaine L, Hough RL, et al: "We never used to do things this way": behavioral health care reform in New Mexico. Psychiatric Services 58:1529–1531, 2007Google Scholar

25. Corrigan PW, Boyle MG: What works for mental health system change, evolution or revolution? Administration and Policy in Mental Health 30:379–395, 2003Google Scholar

26. Peterson M: Health politics and policy in a federal system. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 26:1217, 2001Google Scholar