Smoking Restrictions and Treatment for Smoking: Policies and Procedures in Psychiatric Inpatient Units in Australia

Tobacco smoking is the leading preventable cause of death and disease in Australia ( 1 , 2 ). Even though the prevalence of smoking has decreased to 20% in the general population ( 3 ), high prevalence rates remain for people with psychiatric disorders—32% in community surveys ( 4 ), 41%–74% in outpatient services ( 5 , 6 ), and 70%–90% in inpatient psychiatric units ( 7 , 8 , 9 ). As a consequence, mortality and morbidity resulting from smoking-related diseases are much higher for people with mental illness than for the general population ( 9 , 10 ).

Traditionally, psychiatric services have often reinforced tobacco smoking through use of smoking as a tool to modify behavior ( 11 , 12 , 13 ) and for rapport building ( 13 , 14 ). The need for psychiatric services to reorient policies and procedures and provide treatments to address smoking has been strongly argued ( 9 , 12 , 15 , 16 ). Large proportions of psychiatric patients report having contemplated a quit attempt ( 13 , 17 ). An accumulating number of studies have provided insight into the nature of cessation support that may be required for this population, taking into account factors such as a high level of nicotine dependence, concurrent substance abuse, and prescribed psychotropic medications ( 18 , 19 ).

Not only is it important to provide treatment for smoking to both psychiatric patients and persons in the general population ( 1 , 2 ) and to address the poorer physical health of psychiatric patients ( 10 ), but it is also the duty of health services to protect nonsmoking staff, patients, and visitors from the effects of second-hand smoke. The duty to protect nonsmokers has become a driving force for change in smoking policies and practices in health care settings ( 12 , 15 , 16 , 20 , 21 , 22 ). Research suggests that smoking bans in psychiatric services are accepted by a majority of patients ( 23 , 24 , 25 ). Smoking bans appear to be more successful when consistently applied ( 23 , 24 , 25 ) and when implemented as total rather than partial bans ( 23 , 25 , 26 ). It has also been found that in workplaces ( 27 ) and health care settings generally ( 28 ), a smoke-free environment is supportive of and conducive to smoking cessation or reduction in consumption by both staff and patients ( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ).

In Australia no published research has described smoking policies and smoking care procedures in inpatient psychiatric units, and limited research has been conducted elsewhere ( 30 ). In the state of New South Wales (population approximately seven million), the Smoke Free Workplace Policy ( 20 ) has been introduced in stages since 1999. In 2005 a directive was issued for all health services to move to full implementation ( 31 ). Guidelines for the management of nicotine-dependent inpatients were made available in 2002 by the New South Wales Health Department ( 32 ). The guidelines integrate five steps into routine care: identification of smoking status, provision of support for inpatient abstinence, provision of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), monitoring of withdrawal symptoms, and including a treatment summary in the discharge plan. Although the extent of adoption of these guidelines has been evaluated in general hospital settings ( 33 ), the extent in psychiatric services remains unknown. This study was undertaken to identify policies and procedures in public psychiatric inpatient units in New South Wales, smoking care provided in such units, and policies and procedures associated with assessment of smoking status and provision of smoking care.

Methods

Design, setting, and participants

A cross-sectional survey was undertaken in 2006 of all publicly funded psychiatric inpatient units in New South Wales. A list of public psychiatric inpatient units (N=131) was obtained from the New South Wales Health Department, across eight area health services in the state, four metropolitan and four nonmetropolitan.

Procedure

A survey was developed from questionnaires previously used to assess provision of smoking care in Australian drug treatment agencies ( 34 ) and the New South Wales guidelines for management of inpatients dependent on nicotine ( 32 ). Questionnaires mailed to the nurse unit manager of each psychiatric inpatient unit by the New South Wales chief health officer requested that he or she complete the survey on behalf of the unit. Completed questionnaires were returned to the Health Department, and department personnel followed up with units that did not respond within one month.

Measures

Smoking restrictions. Six questions addressed smoking restrictions for staff and patients. Two yes-no questions assessed the existence of documented smoking policies and smoke detectors in bathrooms and toilets.

Management of staff smoking issues. Four yes-no questions addressed staff smoking practices, adherence to smoking policies, provision of NRT to staff, and occurrence of staff complaints regarding exposure to tobacco smoke.

Smoking care support procedures. Seven questions (yes, no, or unsure) were related to the provision of formal training in smoking assessment and smoking care, the recording of smoking assessment and care, staff discretion regarding smoking assessment and care, and the availability of smoking care guidelines.

Management of patients' access to cigarettes. One yes-no question assessed whether any patients had begun to smoke during their stay. Five questions assessed the proportion of patients whose access to cigarettes was managed either by providing or withholding cigarettes (0%, 1%–25%, 26%–50%, 51%–75%, 76%–99%, and 100%).

Provision of smoking care: assessment, recording, and cessation interventions. Four questions addressed the proportion of smokers whose smoking status was assessed and recorded, and ten questions measured the proportion of smokers who received smoking care (0%, 1%–25%, 26%–50%, 51%–75%, 76%–99%, and 100%). Nicotine dependence could be determined from information about smoking obtained during patient assessment or by use of a formal assessment tool. Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency with which such care was provided (always, frequently, sometimes, or never). Three questions assessed whether changes in assessment, recording the assessment, or provision of smoking care in the previous 12 months had occurred (increased a lot, increased a little, no change, decreased a little, decreased a lot, or don't know).

Characteristics of the unit and nurse unit manager. Respondents were required to classify their unit as being acute or nonacute and locked or not locked, to describe the unit size in terms of number of beds, and to estimate the percentage of nursing staff who smoked (0%, 1%–25%, 26%–50%, 51%–75%, 76%–99%, and 100%). Respondents indicated their job title, length of time in that position, current smoking status, whether they were responsible for enforcing smoking policies, whether they had had training in smoking interventions, and whether they were interested in receiving training.

Analyses

All analyses were undertaken with SAS version 8.2 ( 35 ). Descriptive statistics were used to report the characteristics of participating units and the prevalence of policies and procedures. Response categories for the proportion of patients whose access to cigarettes was managed and to whom smoking assessment and care was provided were collapsed from six to four (0%, 1%–50%, 51%–99%, and 100%).

Possible associations of policies and procedures both with assessment of smoking status and with provision of smoking care were investigated by using chi square analyses (checking for multicolinearity) and stepwise logistic regression, in which variables with a p value of <.25 in the chi square analyses were included. For these analyses, a composite variable score ( 36 ) describing the provision of smoking care was constructed for each unit. The composite variable score (maximum score of 6) was calculated by summing three subcomponents: the percentage of patients who had their smoking status assessed (a score of 2 was given if 100% of patients had their smoking status assessed, 1 if the proportion was 51%–99%, and 0 if the proportion was 50% or less). In calculating the score for the second subcomponent—any type of counseling or advice—nine items were included. A score of 2 was given when any of the nine counseling or advice items were reported as always being provided, 1 if any were frequently provided, and 0 if they were sometimes or never provided. In calculating the score for the third subcomponent—frequency of provision of NRT to patients—a score of 2 was given if NRT was always provided, 1 if it was frequently provided, and 0 if it was sometimes or never provided. The composite variable scores were collapsed into dichotomous categories: a smoking care score of 5 or more, which represented the provision of comprehensive smoking care, versus a score of 4 or lower.

To predict assessment of smoking status, 11 characteristics of the unit and the nurse unit manager and of policies and procedures (all with p values of <.25 in the chi square analyses) were entered into a logistic regression model. The variables were size of unit, proportion of staff smokers less than 25%, documentation of smoking restrictions, enforcement of smoking restrictions, withholding of cigarettes from patients who smoke in order to minimize tobacco-related harm, provision of information and encouragement to staff about use of NRT, adherence to smoking restrictions by staff, routine (not left to staff discretion) assessment of patients' smoking status, routine recording of smoking status, routine provision of advice about quitting to patients by at least some staff, and monitoring of the recording of patients' smoking status on the unit.

To predict the provision of smoking care, eight characteristics of the unit and unit nurse manager and of policies and procedures (all with p values of <.25 in the chi square analyses) were entered into a logistic regression model. The variables were size of unit, nonuse of cigarettes as a reward for patients who smoke, restricted access to cigarettes for patients who smoke, nonprovision of cigarettes to patients when their supply is expended, withholding of cigarettes from patients who smoke in order to minimize tobacco-related harm, provision of information and encouragement to staff about use of NRT, routine (not left to staff discretion) assessment of patients' smoking status, and routine provision of advice about quitting to patients by at least some staff.

Results

Unit and respondent characteristics

Of the 131 psychiatric inpatient units identified, 123 units, with a total of more than 2,000 beds, returned completed questionnaires (94%). Across the eight area health services response rates ranged from 83% to 100%. Unit characteristics are shown in Table 1 .

|

A total of 117 respondents (96%) were nurse unit managers. Eighty-two respondents (67%) reported that they had been in their current role for more than 12 months, and 113 (93%) reported that they were responsible for enforcing smoking policies in the unit. Twenty-six (21%) reported that they were current smokers, 49 (41%) stated that they were former smokers, and 46 (38%) reported that they had never smoked. Twenty (16%) reported they had received formal training about smoking cessation interventions, and 74 (61%) stated they would be interested in receiving such training.

Smoking-related policies and procedures

Smoking restrictions. Although 98% of respondents reported a total ban on smoking indoors, units with a total ban on smoking on verandahs and in courtyards and grounds did not exceed 44% ( Table 2 ). Ninety-nine respondents (81%) reported that smoke detectors were installed in bathrooms and toilets. Nearly two-thirds (N=76, or 63%) reported that existing smoking restrictions were documented in a unit policy.

|

Management of staff smoking issues. Twenty-two respondents (18%) reported that staff smoked with patients. Only 60 (50%) reported that staff who smoked were encouraged to use NRT during their shift. A total of 93 respondents (79%) reported that staff who smoked adhered to smoking restrictions; however, 57 (47%) reported staff complaints about exposure to second-hand smoke.

Smoking care support procedures. Fewer than half of respondents reported that their units provided any type of staff training in smoking assessment (N=52, or 43%) or smoking care (N=46, or 38%). Twenty-seven respondents (22%) reported that unit personnel monitored or audited medical records to ensure recording of patient smoking status, and only nine (7%) conducted monitoring or auditing of documentation of the provision of smoking care to patients. Only 27 respondents (23%) reported that smoking care guidelines were available in the unit. More than half of respondents reported that it was an individual staff member's decision whether to assess a patient's smoking status (N=68, or 57%), record the status (N=74, or 61%), provide smoking care (N=90, or 74%), and determine what type of smoking care to provide (N=80, or 66%).

Management of patients' access to cigarettes. A total of 44 respondents (36%) reported that they knew of instances in which patients who had been nonsmokers before admission began smoking during their inpatient stay. As shown in Table 3 , up to 39% of respondents reported the provision of cigarettes to some patients.

|

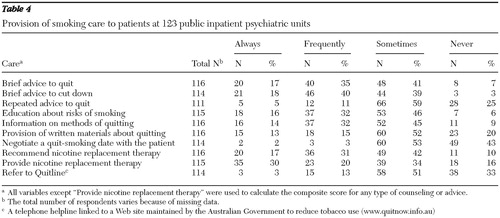

Provision of smoking care

As shown in Table 3 , 50% of respondents reported that all patients were assessed for smoking status. A greater proportion (N=84, or 70%) reported that nicotine dependence was not assessed, either informally or by use of a diagnostic tool. As shown in Table 4 , less than one-fifth of patients who smoked always received advice to quit or were provided information about the risks of smoking. Thirty-six respondents (29%) reported that the frequency of smoking assessment had increased in the past 12 months, and 87 (67%) reported no change. Only 18 respondents (15%) reported an increase in the frequency of recording patients' smoking status, and 97 (79%) reported no change.

|

Associations between policies and procedures and smoking care

As indicated in Table 5 , units where staff provided quit-smoking advice to patients had more than four times the odds of assessing patients' smoking status than units where staff did not provide such advice (odds ratio [OR]=4.10). Units that reported at least sometimes withholding patients' cigarettes to minimize tobacco-related harm had three times the odds of providing smoking care than units where patients' cigarettes were never withheld (OR=3.26).

|

Discussion

The findings suggest that a majority of smoking patients in psychiatric inpatient units in New South Wales receive inadequate and inconsistent smoking care and that staff may be inadequately protected from exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Although most psychiatric units enforced a total smoking ban indoors, no more than one-third of units (N=37, or 34%) had bans in place for all hospital grounds. This finding is consistent with previous research reporting that indoor bans were the predominant type of smoking ban in psychiatric inpatient settings ( 12 ).

Although most nurse unit managers reported that they were responsible for enforcing the unit's smoke-free policy, only two-thirds (69%) reported that enforcement occurred. Previous research has indicated that when smoke-free policies were not consistently enforced, patients and staff tended to smoke without restriction ( 37 , 38 , 39 ). Research has also shown that exposure to environmental tobacco smoke remained high in settings with designated smoking areas ( 25 ). This finding was reinforced in the study reported here; nearly half of respondents (47%) reported that they had received staff complaints about exposure to second-hand smoke.

Eighteen percent of respondents reported that staff smoked with patients. This may reflect an attitude that smoking is an acceptable part of the culture of psychiatric inpatient units ( 40 ) or that cigarettes are seen by patients and some staff as a currency for social exchange ( 41 ). Research in a forensic psychiatric service ( 17 ) and a large psychiatric hospital ( 42 ) found that a majority of psychiatric staff and patients believed that staff should smoke with patients, with more than 90% of staff in both of these studies believing that patients' psychiatric status would deteriorate without access to cigarettes ( 17 , 42 ). Such beliefs are contradicted by evidence that shows that abrupt cessation has no effect on severity of symptoms ( 24 , 43 ) and does not have an impact on recovery ( 43 ). Regardless of their determinants, these beliefs are considered to reinforce smoking behavior among both staff and patients ( 41 , 44 ), an outcome that contradicts health service guidelines internationally ( 21 , 45 ) as well as in Australia ( 20 , 32 ).

The results indicate that in New South Wales the level of adoption of smoking care guidelines in public psychiatric units is lower than in general hospital settings ( 33 ). In the study reported here only half of the units always assessed patients' smoking status and just over a third of units (37%) always recorded smoking status in patients' records. Previous research suggests that there is little benefit to assessing smoking status if this information is not recorded and an appropriate intervention provided ( 46 , 47 ). In addition, 70% of respondents reported that patients were not assessed for nicotine dependence. Failure to diagnose and record nicotine dependence may reflect views of smoking as a choice rather than an addiction ( 48 ) and may result from discretionary procedural guidelines ( 32 ). The latter possibility is supported by the finding that more than half of the respondents indicated that the decision to assess and record smoking status and provide smoking care was at the discretion of staff.

In 2006, when this study was conducted, provision of smoking care was not mandated in psychiatric inpatient units in New South Wales ( 32 ) and is now mandated in only one area of the state. Within this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that few units reported the provision of smoking care that would support abstinence, address withdrawal symptoms, or assist with a quit attempt. Controlling access to cigarettes was identified by respondents as the most frequently used form of smoking-related care, rather than best-practice smoking care alternatives such as providing advice on quitting.

Of concern is that more than one-third of respondents (36%) reported that they knew of patients who had begun smoking after admission. Previous investigators have suggested that this phenomenon stems from peer pressure from other patients to smoke, lack of other available activities, and reinforcement of smoking by the psychiatric unit ( 13 ). In this study reinforcement of smoking was evident by the lack of consistency in the application of policies and procedures in regard to smoking bans, the presence of staff who smoked with patients, and less than optimal levels of smoking care. It has been suggested that legal ramifications may arise if a patient starts to smoke while an inpatient in a public health care setting ( 48 ). Lawn ( 48 ) proposed that if employers are aware that their day-to-day activities involve acceptance and reinforcement of smoking, despite contrary policy guidelines, negligence (in the legal sense) may be established.

There are also litigation concerns regarding an environment that allows and condones development or maintenance of nicotine dependence ( 49 ). In this study respondents reported that staff provided cigarettes to patients who requested them, used cigarettes as a reward for good behavior, and provided cigarettes to patients to prevent negative behaviors. Failure of staff to warn patients of the harms of smoking or to take action to treat their nicotine dependence may leave staff vulnerable to litigation should patients develop smoking-related illnesses ( 50 ). Although this has not been tested in Australia, failure to act appears to contradict duty-of-care responsibilities.

Other studies have reported that psychiatric staff have been cautious regarding the benefits of smoking bans and have been reluctant to provide smoking care in the inpatient setting ( 9 , 50 , 51 ). Inconsistencies in staff management of these issues have led to greater difficulties for inpatients and staff ( 23 , 24 ). In the study reported here, the lack of association between the provision of smoking care and unit characteristics suggests that less than optimal provision of smoking care is systemic and not related to particular types of services (for example, acute or nonacute). The results suggest that units that showed signs of being able to break with traditional smoking-related practices were most likely to have documented unit policies on smoking restriction, staff compliance with smoking restrictions, increased provision of quit-smoking advice, and fewer staff who were smokers.

It has been suggested that staff training is part of the solution for ensuring consistent enforcement of smoking restrictions and provision of smoking care ( 12 ). A small number (16%) of respondents reported that they had received smoking care training, and a majority of respondents (61%) reported interest in receiving such training. Others have also suggested that it is necessary to provide training that addresses skills, knowledge, and attitudes regarding the provision of smoking care and that provides knowledge and encouragement to staff about use of existing resources to improve the provision of smoking care, although it is arguable that such training is not sufficient ( 12 , 52 ). The New South Wales Health Department's existing guidelines for the management of nicotine-dependent patients ( 32 ) provides a ready basis upon which training could be based.

This study relied on a self-reported questionnaire that is susceptible to respondent bias. Inaccurate reporting may have occurred if the respondents were not actively involved in daily smoking care activities. These data collection limitations may have led to misreporting (most likely overreporting) the extent of care provided ( 52 , 53 ).

Conclusions

It has been recommended that all psychiatric facilities move toward being smoke-free institutions ( 9 , 12 , 15 ). Research is required to monitor the provision of smoking care in psychiatric services and to identify strategies that enable the incorporation of smoking care into standard practice. Efforts to address staff reliance on smoking as a means to manage patient behavior are also needed. Until total smoking bans and routine smoking care are adopted in all psychiatric settings, health services continue to convey the message that smoking is an acceptable health behavior to an already health-disadvantaged population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, Australia. The authors thank Elayne Mitchell for assistance with distribution and collection of questionnaires and Michelle Butler, B.Sc. (Psych. and Stats.), Dip.Med.Stat., for assistance with the statistical analysis. The authors also thank the study participants.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Mathers CD, Vos ET, Stevenson CE, et al: The burden of disease and injury in Australia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 79:1076–1084, 2001Google Scholar

2. Somerford P, Katzenellenbogen JM, Codde JP: Impact of health modifiable risk factors on disability and death: overview by age. Bulletin no 5. Perth, Department of Health, Government of Western Australia, 2004Google Scholar

3. The Health of the People of New South Wales: Report of the Chief Health Officer. Sydney, New South Wales Department of Health, Population Health Division, 2006. Available at www.health.nsw.gov.au Google Scholar

4. National Health Survey: Summary of Results. Sydney, Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006Google Scholar

5. Green MA, Clarke DE: Smoking reduction and cessation. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 43(5): 18–25, 2005Google Scholar

6. Fowler IL, Carr VJ, Carter NT, et al: Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:443–455, 1998Google Scholar

7. Goff DC, Henderson DC, Amico E: Cigarette smoking and schizophrenia: relationship to psychopathology and medication side effects. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1189–1194, 1992Google Scholar

8. Reichler H, Baker A, Lewin T, et al: Smoking among in-patients with drug-related problems in an Australian psychiatric hospital. Drug and Alcohol Review 20:231–237, 2001Google Scholar

9. Williams JM, Ziedonis D: Addressing tobacco among individuals with a mental illness or an addiction. Addictive Behaviors 29:1067–1083, 2004Google Scholar

10. Coghlan R, Lawrence D, Holman CDJ, et al: Duty to Care: Physical Illness in People With Mental Illness: Consumer Summary. Perth, University of Western Australia, Department of Public Health and Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Science, 2001Google Scholar

11. Ziedonis DM, Williams JM: Management of smoking in people with psychiatric disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 16: 305–315, 2003Google Scholar

12. Stuyt EB, Order-Connors B, Ziedonis DM. Addressing tobacco through program and system change in mental and addiction settings. Psychiatric Annals 33:447–456, 2003Google Scholar

13. Peele R: Nicotine addiction in the psychiatric hospital: a preliminary report. Psychiatric Journal University of Ottawa 4:239, 1988Google Scholar

14. Lawn S, Pols RG: Nicotine withdrawal: pathway to aggression and assault in the locked psychiatric ward. Australasian Psychiatry 11:199–203, 2003Google Scholar

15. Hughes JR. The future of smoking cessation therapy in the United States. Addiction 91:1797–1802, 1996Google Scholar

16. Prochaska JJ, Fletcher L, Hall SE, et al: Return to smoking following a smoke-free psychiatric hospitalization. American Journal on Addictions 15:15–22, 2006Google Scholar

17. Dickens GJ, Stubbs JH, Popham R, et al: Smoking in a forensic psychiatric service: a survey of inpatients' views. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 12: 672–678, 2005Google Scholar

18. Ziedonis DM, George TP: Schizophrenia and nicotine use: report of a pilot smoking cessation program and review of neurobiological and clinical issues. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:247–254, 1997Google Scholar

19. Baker A, Richmond R, Haile M, et al: Randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention among people with a psychotic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1934–1942, 2006Google Scholar

20. Smoke Free Workplace Policy. Sydney, New South Wales Health Department, 1999Google Scholar

21. McNeill A: Smoking and Patients With Mental Health Problems. London, United Kingdom, National Health Service, Health Development Agency, 2004Google Scholar

22. Matthews LS, Diaz B, Bird P, et al: Implementing a smoking ban in an acute psychiatric admissions unit. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 43:33–36, 2005Google Scholar

23. Lawn S, Pols R: Smoking bans in psychiatric inpatient settings? A review of the research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 39:866–885, 2005Google Scholar

24. Harris GT, Parle D, Gagne J: Effects of a tobacco ban on long-term psychiatric patients. Journal of Behavioural Health Services and Research 34:43–56, 2007Google Scholar

25. Willemsen MC, Görts CA, Van Soelen P, et al: Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and determinants of support for complete smoking bans in psychiatric settings. Tobacco Control 13:180–185, 2004Google Scholar

26. Etter M, Etter J-F: Acceptability and impact of a partial smoking ban in a psychiatric hospital. Preventive Medicine 44:64–69, 2007Google Scholar

27. Shields M: Smoking: prevalence, bans and exposure to second-hand smoke. Health Reports 18(3):67–86, 2007Google Scholar

28. Rigotti NA, Arnsten JH, McKool KM, et al: Smoking by patients in a smoke-free hospital: prevalence, predictors, and implications. Preventive Medicine 31:159–166, 2000Google Scholar

29. Longo DR, Johnson JC, Kruse RL, et al: A prospective investigation of the impact of smoking bans on tobacco cessation and relapse. Tobacco Control 10:267–272, 2001Google Scholar

30. Prochaska JJ, Gill P, Hall SM: Treatment of tobacco use in an inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Services 55:1265–1270, 2004Google Scholar

31. Progression of the NSW Health Smoke-Free Workplace Policy. Sydney, New South Wales Department of Health, Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Advancement, 2005Google Scholar

32. Guide for the Management of Nicotine-Dependent Inpatients. Gladesville, New South Wales Department of Health, Better Health Centre, 2002Google Scholar

33. Walsh RA, Bowman BA, Tzelepis F, et al: Smoking cessation interventions in Australian drug treatment agencies: a national survey of attitudes and practices. Drug and Alcohol Review 24:235–244, 2005Google Scholar

34. Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, et al: Smoking care provision in smoke-free hospitals in Australia. Preventive Medicine 41: 151–158, 2005Google Scholar

35. SAS Version 8.2. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2000Google Scholar

36. Richter KP, Choi WS, McCool RM, et al: Smoking cessation services in US methadone maintenance facilities. Psychiatric Services 55:1258–1264, 2004Google Scholar

37. Thorward SR, Birnbaum S: Effects of a smoking ban on a general hospital psychiatric unit. General Hospital Psychiatry 11: 63–67, 1989Google Scholar

38. Greeman M, McClellan TA: Negative effects of a smoking ban on an inpatient psychiatric service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:408–412, 1991Google Scholar

39. Parks JJ, Devine DD: The effects of smoking bans on extended care units at state psychiatric hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:885–886, 1993Google Scholar

40. Dickens GL, Stubbs JH, Haw CM: Smoking and mental health nurses: a survey of clinical staff in a psychiatric hospital. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 11:445–451, 2004Google Scholar

41. Lawn SJ: Systemic barriers to quitting smoking among institutionalised public mental health service populations: a comparison of two Australian sites. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 50:204–215, 2004Google Scholar

42. Stubbs J, Haw C, Garner L: Survey of staff attitudes to smoking in a large psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Bulletin 28:204–207, 2004Google Scholar

43. Smith CM, Pristach CA, Cartagena M: Obligatory cessation of smoking by psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 50:91–94, 1999Google Scholar

44. Ziedonis DM, Williams JM, Smelson D: Serious mental illness and tobacco addiction: a model program to address this common but neglected issue. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 326:223–230, 2003Google Scholar

45. Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen S: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guidelines. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2000Google Scholar

46. Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Schensky AE, et al: Smoking status as the new vital sign: effect on assessment and intervention in patients who smoke. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 70: 209–213, 1995Google Scholar

47. Currell R, Wainwright P, Urquhart C: Nursing record systems: effects on nursing practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3:CD002099, 2003Google Scholar

48. Lawn S: Cigarette smoking in psychiatric settings: occupational health, safety, welfare and legal concerns. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 39:886–891, 2005Google Scholar

49. Lawn S, Condon J: Psychiatric nurses' ethical stance on cigarette smoking by patients: determinants and dilemmas in their role in supporting cessation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 15:111–118, 2006Google Scholar

50. Sweda EL: Lawsuits and secondhand smoke. Tobacco Control 13:61–66, 2004Google Scholar

51. Foulds J: The relationship between tobacco use and mental disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 12:303–306, 1999Google Scholar

52. Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Lomas J, et al: Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 11:187–192, 1999Google Scholar

53. Cooke M, Mattick RP, Campbell E: The influence of individual and organizational factors on the reported smoking intervention practices of staff in 20 antenatal clinics. Drug and Alcohol Review 17:175–185, 1998Google Scholar