Implementation of Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment: A Qualitative Analysis of Facilitators and Barriers

Approximately half of the people with severe mental illnesses—schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression—experience a co-occurring substance use disorder (abuse or dependence) at some point in their lifetime ( 1 ). People with dual disorders experience worse outcomes than those with single disorders ( 2 ). Integrated dual disorders treatment provides comprehensive, stagewise services to address the serious mental illness and the substance use disorder together in one comprehensive treatment package ( 3 ).

Although a large number of studies have shown that this or similar integrated programs improve many outcomes for consumers ( 4 ), the findings are not consistent. The more rigorous studies, summarized by Jeffery and colleagues in a Cochrane Review ( 5 ), demonstrated that integrated treatment was superior to comparison treatments on some outcomes but not others and varied from study to study. Despite a growing interest in integrated treatment, practices that hold promise for persons with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, such as integrated dual disorders treatment, are still not widely available in public mental health settings ( 6 , 7 ).

To facilitate the expansion of integrated services in public mental health, research is needed to demonstrate what types of implementation strategies are effective ( 10 ). In addition, information regarding facilitators and barriers to successful implementation could help in the planning and execution of service implementation.

Although a large body of research has evaluated some aspects of implementing programs in health and human services, less is known about implementation in public mental health settings. Fixsen and colleagues ( 8 ) recently reviewed and summarized this literature on practice implementation, concluding that facilitators and barriers to the adoption of new programs can occur at multiple levels and that significant research gaps remain. Notably, of the 743 relevant articles they reviewed, 20 reported the results of experimental studies. These implementation studies took place in education, managed care, and medicine, rather than in public mental health settings. Research that has thus far documented implementation of programs in public mental health settings has been primarily case studies, summaries, and guidelines based on practical experience of implementation ( 9 ).

To learn more about service implementation in public mental health settings, the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project investigated the implementation of five psychosocial practices in 53 routine mental health settings across eight states.

Implementation was assisted by an intervention package that included provision of a toolkit and access to a consultant-trainer for two years. Fidelity to each service model was measured at six-month intervals over two years and at a two-year follow-up. The initial analysis of implementation in this parent study found that more than half the sites were able to implement one of the five practices with high fidelity to the model of practice, but variation occurred across practices ( 11 ). Integrated dual disorders treatment was one of the practices that fewer organizations implemented with high fidelity. Although several other reports have addressed some aspects of implementation from the parent study ( 12 , 13 , 14 ), this report describes the extent to which organizations implemented integrated dual disorders treatment. This study then used qualitative methods to elucidate concomitant facilitators and barriers to implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment.

Methods

Participants

The unit of analysis was each community mental health center that participated in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project. Thirteen agencies in three states volunteered and were chosen to participate in the study of integrated dual disorders treatment implementation. State mental health authority directors or their designees were instructed to independently select agencies that represented the array of agencies in their state, that were of average competency, and that were interested in implementing integrated dual disorders treatment and willing to do so. Thirteen agencies were selected. Two agencies dropped out immediately after the baseline assessment when they learned more about implementation of the practice, leaving 11 agencies that completed the two-year project. Agency employees gave written informed consent before participation. The Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects reviewed and approved the project.

Implementation support

The model of implementation for this project was developed by implementation experts who used the available research on organizational change and technology transfer ( 15 , 16 ). This research on implementation suggests that implementation efforts tend to be more successful when educational materials and training are supplemented by consultation, implementation support, and feedback and that organizations implementing more complex practices may benefit from more implementation support.

The model in this study involved a lead consultant-trainer who used a standardized set of procedures and materials that were packaged into an implementation resource kit ( 17 ). The kit included written information developed for stakeholders, tips for leaders, training tools (training slide sets and videos), and learning tools (demonstration videos and workbooks). The resource kit cued implementation in stages (preparation, startup, and maintenance) and recommended engaging community, agency, and consumer stakeholders. The consultant-trainer facilitated implementation by assisting each site with choosing a steering committee, advising implementation leaders and the steering committee over two years, conducting staff training for the practice, and being available to answer questions throughout the implementation. Program quality was monitored with a formal fidelity rating and report every six months. The report was provided to the steering committee and leaders as feedback and guidance about the quality of the developing service and to help them modify and further implement the service.

Quantitative data collection

The main quantitative outcome was the degree to which the new service adhered to established principles for integrated dual disorders treatment. Overall fidelity methods and results were previously reported ( 11 ). To contextualize the facilitators and barriers to implementation, integrated dual disorders treatment fidelity scores are reported here in more detail to identify organizations that implemented the practice to a greater or lesser degree.

Qualitative data collection

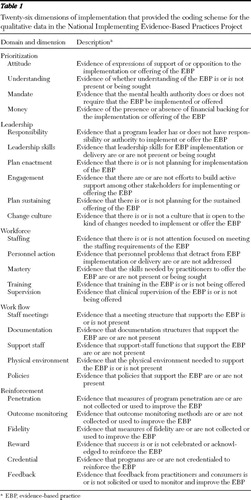

The main qualitative outcomes of interest were the facilitators and barriers to implementation. Twenty-six dimensions (see Table 1 ) that were hypothesized to be important to the implementation process, nested within five broad domains, were designated a priori through consultation of relevant literature ( 8 ) and discussion among implementation experts.

|

Research staff, trained as implementation monitors, functioned as independent observers. They documented implementation efforts over two years with standardized and systematic methods to ensure rigor and comparability across sites and monitors. Monitors visited sites monthly in the first year and every other month in the second year to observe implementation planning meetings, clinical team meetings, and other activities related to implementation, as well as to talk with clinicians, administrators, and consumers. The ethnographic observations from these visits were documented in field notes. In addition, at six-month intervals, the implementation monitors (one at each site) conducted and taped semistructured interviews with the consultant-trainer and the program leader. All interviewers were trained to follow a standardized topic guide designed to elicit opinions and experiences regarding facilitators and barriers to implementation. These interviews included a series of open-ended questions, beginning with "How is the implementation going?" and ending with "What are the barriers to implementation here?" Interviewer reliability was facilitated by regular supervision. Interview tapes were transcribed and imported into Atlas.ti, a software program for qualitative analysis, as were field notes and other sources of information.

Quantitative analysis

Paired t tests were used to assess change in mean fidelity scores from baseline to two years.

Qualitative analysis

Because this was a large study with multiple sites and a large data collection staff, a combined deductive-inductive model for analyzing the qualitative data ( 18 ) was undertaken in a three-step process. First, the implementation monitor at each site coded the qualitative interviews and the field notes from site visits according to the 26-dimension scheme in Table 1 . Once the data from the two-year period had been collected and coded, the implementation monitor rated each theme within each dimension on the degree to which it served as a facilitator or barrier to implementation; possible ratings ranged from 2 (strong facilitator) to 0 (neither facilitator nor barrier) to -2 (strong barrier). At the end of implementation, the monitors wrote a report for each site, including a detailed table of facilitators and barriers categorized into the five domains and 26 dimensions described above. These reports followed a standardized format and provided the basis for the cross-site analysis reported herein. Implementation monitors were trained and supervised by the lead research team. To maintain consistency of the coding and ratings, implementation monitors independently coded and extracted themes from common documents and then discussed their choices during supervision meetings throughout the study.

The second step of analysis distilled the three most prominent facilitators and barriers among the 26 dimensions at each site. A theme was defined as prominent when it had a rating of 2 or -2 in the dimension display, was emphasized in the report synopsis, and was spoken of in strong or persuasive language in interviews and field notes recorded in the Atlas.ti database. Using a standard qualitative data analysis technique ( 19 ), we used several layers of rating of facilitators and barriers to distill out the most prominent factors. Two lead analysts and four supporting analysts carefully reviewed each site report. The two lead analysts independently extracted the main three facilitators and barriers for each site, reported and reviewed the ratings with the analyst group, and then came to consensus on the prominent facilitators and barriers for that site. We found a strong degree of agreement between the two lead analysts. Although codes were designated and grouped a priori, the analytic team allowed the data to drive renaming or regrouping of themes, which occurred in some cases. For example, although attitude is listed under the domain "priority," the analysts found that the attitudes of the leaders were frequently referred to as a facilitator or barrier. Attitude was therefore considered part of leadership.

The third step was to distill the prominent common facilitators and barriers across all 11 sites. After all site facilitators and barriers had been chosen, the analyst group compared and contrasted the main facilitators and barriers for all 11 sites, discussed them, and examined examples and supporting quotes to establish common and predominant implementation facilitators and barriers. Broad themes, if present, were sought. Facilitators from higher-fidelity sites and barriers from lower-fidelity sites were emphasized. This form of multistep coding is considered a robust check and balance on rigor in qualitative research ( 19 ).

Results

The mean±SD integrated dual disorders treatment fidelity score at the 11 sites rose from 2.41±.55 at baseline to 3.42±.54 at 24 months (paired t test=-3.67, df=10, p=.004). (Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater fidelity.) At the two-year point, two sites achieved high fidelity (a score of ≥4.0), six sites achieved moderate fidelity (≥3.0 and <4.0), and three sites remained at low fidelity (<3.0).

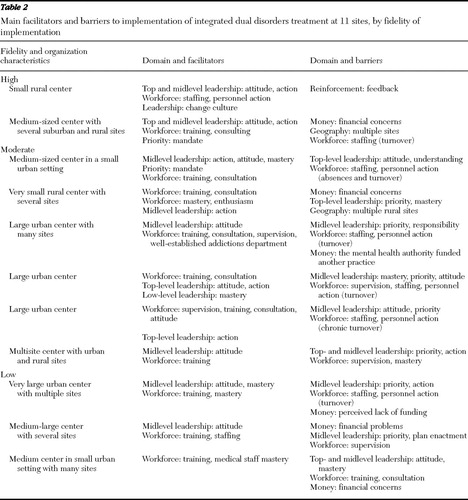

The main facilitators and barriers for each site that emerged from the second layer of analysis are summarized in Table 2 . Five common themes then emerged in the third step of analysis: administrative leadership, consultation and training, supervisor mastery and supervision, chronic staff turnover, and finances. Each theme could influence implementation positively or negatively, depending upon its presence and quality.

|

Leadership

Administrative leadership was noted as a significant factor in implementation at every site. Successful sites tended to have a committed midlevel leader who had sufficient authority to make changes within the organization. Three components of leadership emerged: attitude, priority, and action.

Administrative leaders' attitudes set the tone and modeled appropriate staff responses to the challenges of starting a new service. Attitude alone, however, was insufficient. Leaders at successful (high-fidelity) sites made implementation a priority among their myriad, competing responsibilities, and they took action by making administrative and policy changes to implement the new practice. Action steps varied, including hiring, changing, or firing staff; changing the structure and focus of supervision; changing the treatment plan formats; and implementing new policies and practices for screening for and assessing substance use. Leadership action overcame barriers, such as staff turnover, in the implementation process. Notably, many of the successful agencies assigned implementation leadership to two administrators, one with administrative skills and one with advanced clinical expertise, who shared leadership tasks.

Organizations that implemented the service with low fidelity experienced problems with leadership. Some had enthusiastic leaders who, amid competing demands, were unable to prioritize implementation and take facilitative action. As one steering committee member put it, "The agency takes on these projects without allocating internal resources to make them succeed." Other organizational leaders appeared unable or unwilling to take action to implement the practice, despite the agency's agreement with the state authority or training center.

Consultation and training

Successful organizations utilized the consultant-trainer for two key functions: consultation for initial and ongoing implementation plans, including the type and timing of implementation activities; and training staff and leaders in the information and skills necessary to deliver the service. Consultation efforts varied; some efforts focused on initiating facilitators, and others focused on overcoming a variety of barriers. At some sites, consultation focused on policies and organizational structures to support the practice, while at other sites consultation focused on helping administrators learn leadership and supervisory skills.

Because the delivery of integrated dual disorders treatment requires skills in assessment and counseling that many public mental health clinicians may not have—for example, motivational interviewing and substance abuse counseling—the agencies either hired staff who possessed these skills or, in most cases, trained existing staff. Successful sites supplemented classroom training with regular supervision (see next section). At some centers, the consultant-trainer attended team meetings to provide supervision between monthly classroom-style trainings; at other centers, agency leaders were able to function in this key capacity.

Although many informants reported that the toolkit materials were helpful, most stated that the materials were less important than interactions with the consultant-trainer. Many project leaders made such comments as, "It's easier to call (or e-mail) someone than to look it up." The presence of the consultant-trainer was viewed as encouraging and appeared to boost morale during the challenges of organizational change.

Although skilled consultation to the agencies was helpful, unskilled consultation was harmful. In some cases, a consultant-trainer did not work well with leaders and appeared to confuse and hinder the implementation process. In addition, some low-fidelity sites received poor-quality training or simply did not allow employees to attend training.

Supervisor mastery and supervision

Many observers noted that clinical leaders require mastery of service-specific knowledge and skills in order to provide ongoing staff training and supervision. Most leaders developed these skills during the study. As one implementation monitor stated, "Supervision played a key role in the success of the integrated dual disorder treatment team."

The absence of high-quality clinical supervision was a common barrier observed in organizations with moderate or low fidelity.

Staff turnover

Many of the 11 organizations experienced significant staff turnover. In some, change in staffing facilitated implementation by moving unwilling staff to other positions, terminating incompetent staff, or hiring new staff who were willing and competent. Abrupt turnover of multiple staff was perceived as a barrier, although several organizations overcame this problem and attained reasonably high fidelity by immediate rehiring and training. Chronic staff turnover, however, appeared to be a much more difficult barrier, creating heavier training and supervisory challenges that some leaders were unable to meet. In addition, some of these teams were short-staffed for long periods, resulting in high caseloads. One case manager stated, "We are so overwhelmed we don't have time to practice the [integrated dual disorders treatment] techniques." It appeared in some cases that staff turnover was related to leadership problems with hiring, supervision, and other implementation support. One organization with chronic turnover was able to accept advice from the consultant-trainer to change hiring practices to reduce turnover, including utilizing team members in the hiring process, allowing job candidates to shadow experienced practitioners, and providing additional supervision to new practitioners.

Finances

In organizations that implemented the model with low fidelity, staff and leaders often expressed concern about the financial implications of making organizational changes, including allotting time for staff training, providing supervision, and reducing caseload size. One project leader stated, "Every time I've got a clinician sitting in a meeting … it's costing me money." These concerns occurred despite some funding (less than $10,000) to defray implementation costs and the provision of free training and consultation. In one state a simultaneous initiative to implement assertive community treatment competed with the implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment, in part because additional funds were offered for assertive community treatment implementation. This situation led one organization to abandon integrated dual disorders treatment implementation entirely. The program leader stated, "We are going to do whatever they … pay for."

At least one financially strapped organization was nevertheless able to overcome this barrier with leadership priority and consultation, implementing the service model with excellent fidelity. Successful organizations reported that their treatment teams were financially viable because Medicaid and Medicare payments for the clinical services covered the cost of running the services in those agencies.

Other facilitators and barriers

Several other themes arose that deserve mention. One facilitator embedded in this model of implementation was the use of regular fidelity measures to assess service quality and to provide feedback to leaders. Leaders at successful sites used these reports to develop action plans to further their implementation efforts. Another important facilitator was the integration of the agency's quality improvement actions with the implementation efforts. A third was each organization's relationship with the state or county mental health authority, which could help or hinder the process.

Discussion

Integrated dual disorders treatment was implemented with varying degrees of success at the 11 participating organizations. We found that facilitators and barriers, consistent with other independent reports from this project ( 13 , 20 ), occurred at the clinician level (staff skills and turnover), at the organization and administration level (leadership and supervisor mastery and supervision), at the level of the implementation model (consultation, training, and fidelity feedback), and at the environmental-state authority level (financing and the relationship with the mental health authority).

This study confirmed research in other fields suggesting the need for multilevel active implementation efforts and at the same time highlighted the importance of the organization's administrative leader and of the consultant-trainer. Even with intensive efforts at multiple levels, however, most organizations did not achieve high-fidelity implementation. Integrated dual disorders treatment is a complex service that contains multiple components and requires change at the provider, organization, and environment levels. For these reasons, this service may be more difficult to implement than single-component practices, such as cognitive therapy to treat major depression.

Financial concerns and financing emerged as a barrier that has particular salience in the current public mental health environment. Financing is related to the other facilitators and barriers and therefore must be addressed by systems wishing to implement these programs. First, federal and state mental health authorities that desire high-quality service implementation must provide adequate reimbursement for these services ( 21 ), or provider organizations simply will not deliver them. Second, integrated dual disorders treatment requires skills that may be new to many public mental health providers (for example, substance abuse counseling and motivational interviewing) as well as structural change (for example, lower caseloads for workers who treat clients with dual disorders and the provision of group therapy). Thus organizations that are starting to implement the service should plan for temporary reductions in billing while staff members take time from direct service delivery to learn new skills and to restructure services and systems. Mental health authorities wishing for broad implementation should expect modest lulls and provide financial support for organizations during this period.

Third, mental health authorities and organizations must fund mechanisms to monitor fidelity or quality of service delivery, which can be aligned with ongoing quality improvement strategies ( 22 ). The regular conduct of fidelity assessments and immediate feedback to leaders regarding fidelity was an inherent part of implementation that also required additional administrative staff time, which affects the cost of providing services. Finally, financial incentives to encourage organizations to implement evidence-based practices should be utilized ( 23 ). Two other reports addressing state-level activities related to implementation in this large project confirmed that attention to financing and monitoring at the state level facilitated implementation within the organization ( 12 , 13 ).

This study used established qualitative research methods to elucidate facilitators and barriers at a range of organizations in several states. However, the study has several potential limitations. First, all the participating organizations volunteered to implement the service, potentially biasing the outcomes toward more positive results than would occur if we had, for example, attempted to implement the service statewide in all three states. In addition, this study assessed only one model of implementation, which used toolkit materials and an in-person consultant-trainer. Other models of implementation might result in different rates of success as well as different facilitators and barriers.

Conclusions

Organizations and mental health authorities can use information on facilitators and barriers to plan for effective and efficient implementation of services in their localities. Further research is needed to examine how these facilitators and barriers influence the sustainability of integrated dual disorders treatment and other programs over time, what strategies can overcome implementation barriers, which components of this implementation model are necessary and sufficient, and whether different implementation support models are useful for different types of organizations and organizations at different levels of motivation to implement a new practice.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by the West Family Foundation, the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the Johnson & Johnson Charitable Trust.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 264:2511–2518, 1990Google Scholar

2. Dixon L, Haas G, Weiden P, et al: Acute effects of drug abuse in schizophrenic patients: clinical observations and patients' self reports. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:69–79, 1990Google Scholar

3. Mueser KT, Noordsy D, Drake RE, et al: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders: A Guide to Effective Practice. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

4. Drake RE, O'Neal EL, Wallach MA: A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 34:123–138, 2008Google Scholar

5. Jeffery DP, Ley A, McLaren S, et al: Psychosocial treatment programmes for people with both severe mental illness and substance misuse. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2000Google Scholar

6. Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, et al: Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:469–472, 2001Google Scholar

7. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

8. Fixsen D, Naom SF, Blase KA, et al: Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. FMHI pub 231. Tampa, University of South Florida, Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network, 2005Google Scholar

9. Gold PB, Glynn SM, Mueser KT: Challenges to implementing and sustaining comprehensive mental health service programs. Evaluation and the Health Professions 29:195–218, 2006Google Scholar

10. Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K: Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: what matters when? Psychiatric Services 52:1190–1197, 2001Google Scholar

11. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Whitley R, et al: Fidelity outcomes in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatric Services 58:1279–1284, 2007Google Scholar

12. Isett KR, Burnam MA, Coleman-Beattie B, et al: The state policy context of implementation issues for evidence-based practices in mental health. Psychiatric Services 58: 914–921, 2007Google Scholar

13. Moser LL, DeLuca NL, Bond GR, et al: Implementing evidence-based psychosocial practices: lessons learned from statewide implementation of two practices. CNS Spectrums 9:926–936, 2004Google Scholar

14. Woltmann EM, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, et al: The role of staff turnover in the implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatric Services 59: 732–737, 2008Google Scholar

15. Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 52:45–50, 2001Google Scholar

16. Torrey WC, Finnerty M, Evans AC, et al: Strategies for leading the implementation of evidence-based practices. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 26:883–897, 2003Google Scholar

17. Brunette MF, Drake RE, Lynde D, et al: Toolkit for Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002Google Scholar

18. Miles M, Huberman A: Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1994Google Scholar

19. Barbour RS, Barbour M: Evaluating and synthesizing qualitative research: the need to develop a distinctive approach. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 9:179–186, 2003Google Scholar

20. Woltmann EM, Whitley R: The role of staffing stability in the implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment: an exploratory study. Journal of Mental Health 16:757–779, 2007Google Scholar

21. Goldman HH, Azrin ST: Public policy and evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 26:899–917, 2003Google Scholar

22. Hermann RC, Chan JA, Zazzali JL, et al: Aligning measurement-based quality improvement with implementation of evidence-based practices. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 33:636–645, 2006Google Scholar

23. Day S: Issues in Medicaid policy and system transformation: recommendations from the President's Commission. Psychiatric Services 57:1713–1718, 2006Google Scholar