The Relationship Between Substance Use Patterns and Economic and Health Outcomes Among Low-Income Caregivers and Children

Treatment outcome studies have demonstrated the efficacy of pharmacological and behavioral interventions to reduce drug and alcohol use in heterogeneous populations ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ), and the effect of treatment on a number of psychosocial outcomes including employment has also been demonstrated ( 3 ). Women have been shown to have substance abuse treatment outcomes that are equal to or better than those of men ( 6 ), but barriers to women's treatment entry and retention have been noted ( 6 ), including more child care needs ( 7 ), less insurance ( 8 ), less employment ( 9 ), and higher levels of other economic barriers ( 10 ). Although the adverse effects of substance abuse on work outcomes have been documented ( 11 , 12 ), studies of work outcomes after treatment yield mixed results ( 13 , 14 ). Furthermore, studies often use predominantly male samples ( 15 ). Over the lifetime, women are less likely than men to enter substance abuse treatment ( 5 ), despite evidence that such treatment benefits women and any dependent children in their care ( 16 ).

Among low-income women, demonstration projects report that long-term residential substance abuse services may not only decrease substance use but may also reduce reliance on public health and income programs and improve other areas of functioning, including parenting attitudes and employment ( 17 , 18 ). Nevertheless, there remains a lack of information on the complex interactions between substance use, employment, and self-sufficiency (measured as the absence of reliance on public income programs) among low-income women who are also more likely than their male counterparts to be primary caregivers for children ( 19 ). Such information is critical to a range of social and health care policies that affect the well-being of caregivers and their children, particularly during periods of ongoing reforms to welfare, or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF).

Using survey data on low-income female caregivers, this prospective study asked how patterns of substance use relate to work status, public program use, and well-being. More specifically, we tested two hypotheses. First, we examined whether caregivers with moderate or heavy substance use (that is, moderate or heavy use reported in both interviews or increased substance use over the study period) were less likely to work and more likely to participate in public income assistance or health insurance programs than caregivers with light or no substance use. Second, we tested whether measures of mental well-being for caregivers and children are worse when caregivers report moderate or heavy substance use. We also tested a secondary hypothesis stating that caregivers who reduced substance use between the baseline and follow-up interviews would have outcomes that did not differ from those of caregivers who reported light or no substance use during the study period.

Methods

Conceptual framework

Like others who have studied the impact of substance use on economic outcomes, we draw on the theoretical framework proposed by Becker ( 20 ) and applied to health by Grossman ( 21 ). The key insight of these models is that utility is influenced by health, both directly and indirectly. Health influences utility indirectly because it contributes to productivity both at work, in the form of wages, and at home, by affecting the ability to raise children, for example. In the context presented here, heavy substance use can be viewed as one dimension of health and as a (negative) input to physical and mental health and thus productivity. Such a model predicts that heavy substance use would lower the probability of work, relative to public assistance or other options; worsen symptoms of mental health; and contribute to poor child behavior. Testing for such relationships is challenging because substance use and outcomes of interest may be related to some common factor other than substance use. To help address this confounding, we estimated how changes in outcomes are related to patterns of substance use. We also acknowledge the possibility that confounding factors could change substance use and our outcomes of interest simultaneously.

Overall design

To assess how patterns of substance use are related to economic outcomes and well-being among low-income female caregivers and children, we estimated two sets of models using interview data from the Welfare of Children and Families study. Data were analyzed from baseline interviews that were conducted from March through December 1999 and follow-up interviews that were conducted 11 to 26 months after baseline (average, 16 months). We first modeled, at the time of follow-up, the likelihood of working, collecting income assistance (welfare or disability benefits), or neither working nor collecting income assistance (that is, being "detached") as a function of substance use patterns. Because we controlled for baseline work and income assistance, these follow-up models can be viewed as models of changes in work and public assistance status. Second, we modeled several measures of well-being as a function of substance use patterns: changes in caregiver mental health symptoms, changes in child behavior as reported by the caregiver, and changes in health insurance status of caregivers. Together, these analyses provide a picture of how substance use patterns and policy levers might influence work, public program use, and selected measures of well-being.

Description of data and sample

We used longitudinal data from the first two waves of the Welfare of Children and Families, or the Three-Cities Study, describing circumstances of low-income female caregivers living under 200% of the federal poverty level in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio ( 22 ). In March through December 1999, a total of 2,402 "focal" children aged zero to four or ten to 14 and their primary female caregivers were sampled. Information on work status, public program participation, mental health, and substance use of caregivers, as well as child behavior, caregiver demographic characteristics, and household structure were gathered through in-person interviews with caregivers conducted via a computerized instrument. The sample targeted children ages zero to four or ten to 14 because these ages mark major transitions for children and because for children living with female caregivers who work, these ages represent a time when preschool-age children "require high quality child care" and older children "require more intense supervision and scholastic guidance" ( 22 ). The survey oversampled blacks and Hispanics. Follow-up interviews were conducted with the same caregivers between September 2000 and June 2001.

Of the 2,402 women interviewed in 1999, a total of 384 women were not interviewed at follow-up and were excluded. There were no significant differences in moderate substance use, use of marijuana or other illicit drugs, and the probability of working at baseline between those who left the study and those who completed the follow-up interview. We further excluded 348 caregivers because they (N=152) or someone in their household (N=196) received Supplemental Security Income (SSI) at baseline; however, caregivers remained in the sample regardless of SSI receipt at follow-up. This allowed us to focus on transitions into SSI, which provides income assistance for poor individuals with a long-term disability. Terminations of SSI cases are rare, and once on SSI, recipients typically do not transition out of it. To focus on working-age caregivers, we excluded an additional 40 women who were younger than 18 or older than 64. We excluded seven women who were missing information on race, TANF status, work status, or Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) scores, leaving 1,623 women in our sample.

Substance use patterns

Caregivers reported their substance use in the past 12 months. An ideal measure of substance use would capture symptoms of abuse and dependence or both frequency and quantity of substance use; however, this information was not available in the Three-Cities Study. However, several studies demonstrate significant correlation between even relatively crude measures of substance use with measures of treatment need, substance abuse, and substance dependence ( 2324 , 25 ), something we confirmed among women age 18 and older in the 2002 National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Substance use measures (based on either one or more occasions of having five or more drinks at a sitting or use of any illicit drug in the past 30 days) were significantly correlated with having either abuse or dependence ( ρ =.37, p<.01).

We categorized substance use patterns in two steps. Respondents were asked, "In the last 12 months, how often were you drunk?" Women were also asked, separately for marijuana and other illicit substances, "In the last 12 months, how often did you use?" Possible responses to all three questions included "never," "once or twice," "several times," or "often." In the first step, for each interview, we categorized a respondent's use as light or no use if respondents answered "never" or "once or twice" to all three questions (that is, frequency of drunkenness, marijuana use, and illicit substance use). Otherwise, use was categorized as moderate or heavy. We distinguished moderate or heavy use of alcohol and drugs from any use because previous research suggests that moderate to heavy substance use is most likely to coincide with substance-related harm and to reduce the probability of work and earnings ( 12 , 26 , 27 ). [A table showing substance use patterns by type of substance is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

In the second step, we created four patterns of substance use based on substance use at baseline and follow-up: light or no use at both interviews (N=1,377); moderate or heavy use at both interviews (N=56); increased use during the study period (that is, light or no use at baseline and moderate or heavy use at follow-up) (N=99); and reduced use during the study period (that is, moderate or heavy use at baseline and light or no use at follow-up) (N=91). Because of the small sample of women with moderate or heavy use and because women with moderate or heavy use and women with increased use were expected to have worse trends in outcomes, we combined both of these categories into a new category called moderate or heavy substance use to improve precision.

Outcome measures

We first assessed work and public program participation outcomes at follow-up; data from follow-up, rather than baseline, were analyzed to prevent the possibility of reverse causation or that a change in work or public program use "caused" women to change their substance use. We examined the likelihood of caregivers being in one of three mutually exclusive categories at follow-up: working now with or without receiving TANF or SSI, receiving TANF or SSI without working now, or neither working now nor collecting income assistance now (that is, being "detached"). Among this sample of predominantly unmarried, low-income female caregivers, we interpret the detached state as unfavorable, because it likely indicates a lack of resources.

Because Medicaid coverage and health insurance more generally offer important avenues to access substance abuse treatment services, we assessed health insurance status for the sample of women. We used caregiver reports of Medicaid coverage at follow-up and determined whether caregivers lost or gained health insurance coverage during the study period.

We analyzed two measures of mental well-being—caregiver mental health symptoms and child behavior problems reported by the caregiver. An increasing number of studies suggest that maternal mental health in general and maternal substance use in particular negatively influence a range of child outcomes ( 28 , 29 ). To assess caregiver mental health, we used the BSI ( 30 ), in which female caregivers responded to 18 items relating to anxiety, depression, and somatization. These items were converted into an overall measure of poor mental health, with higher values indicating more symptoms. This measure is highly correlated with the existence of a diagnosable mental health disorder ( 30 , 31 ). We created a binary measure of improved mental health—that is, a decrease of one standard deviation in the log-transformed BSI total mental health measure during the study period. Although this measure has not been used previously, the cutoff for poor mental health indicative of a likely diagnosis of a mental disorder is one standard deviation above the mean ( 20 ). Thus, if everyone in our sample had a decrease of one standard deviation in BSI scores, the share of women at baseline who would exceed the cutoff for poor mental health would fall from 7.6% to 0%. A rise of one standard deviation in BSI scores for our sample would result in 37% exceeding the cutoff for poor mental health.

To measure child behavior problems, we used caregiver responses to the multi-item Child Behavior Check List (CBCL) for children ages two to three and a separate CBCL for children ages four to 18 ( 32 , 33 ), excluding 393 children younger than two at baseline (N=1,230). Similar to the BSI measure, higher scores indicate worse child behavior ( 32 , 33 ), and we formed a variable equal to 1 if the focal child's CBCL score fell by one standard deviation between the two interviews.

Analyses

We estimated two types of outcome models. First, to estimate the effect of substance use patterns on working, receiving income assistance (TANF or SSI), or being detached at follow-up, we estimated multinomial logit models of this three-category variable as a function of indicators for reduced substance use and moderate or heavy substance use, rendering light or no substance use as the reference category. Each model controlled for education, marital status and cohabitation, race and ethnicity, city, and age of respondent at follow-up and work status and use of TANF at baseline ( Table 1 ). In a second set of models of health insurance coverage, improvements in BSI scores, or improvements in CBCL scores, we estimated logistic regression models with the same controls as above.

|

For each result, we display the adjusted probability of the outcome, or the average marginal effect of substance use patterns based on the model coefficients. Given relatively modest sample sizes of caregivers who changed substance use patterns, we report results with borderline statistical significance, or p values under .10. [An appendix showing three tables with the full set of odds ratios (logit models) or relative risk ratios (multinomial logit models) is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] Analyses were conducted with Stata software (version 9.0). All estimates used sample weights provided in the Three-Cities Study data to make estimates representative of the target population of low-income caregivers and children in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio. As recommended by study investigators to prevent results from being skewed toward a single city, weights were scaled such that each city counted equally toward estimates. The Harvard Medical School Human Subjects committee deemed this study exempt from institutional review.

Results

The caregivers in the Three-Cities Study sample had widely varied backgrounds and experiences. At baseline, the modal living arrangement was unmarried and without a cohabiting partner (62%), 44% were working, and 69% were Medicaid enrollees ( Table 1 ). Between the two interviews, 10% lost health insurance coverage, and 15% gained insurance coverage. Between the two interviews, 13% of caregivers experienced a substantial worsening of mental health symptoms, as measured by BSI scores, but 17% had improved mental health symptoms. Twelve percent reported moderate to heavy substance use in at least one interview, and 88% reported light or no drug use in both interviews.

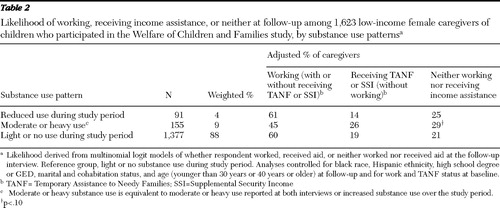

Table 2 reveals how work status and use of TANF or SSI varied by substance use. Women with reduced substance use resembled women with light or no substance use. At the follow-up interview, women with reduced substance use used income assistance and reported working at rates that did not differ significantly from those of women with light or no use. In contrast, compared with caregivers with light or no use, caregivers with moderate or heavy substance use were more likely to be detached (21% versus 29%, p=.051), although this finding was only borderline significant. Caregivers with moderate or heavy use were also more likely to receive TANF or SSI without working (26% versus 19%, p=.108), although this finding was not significant.

|

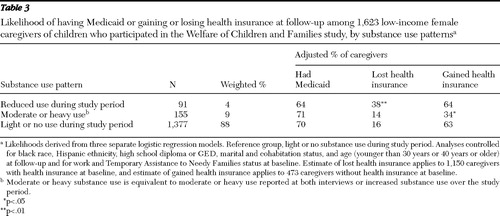

Table 3 shows a surprising finding: although women who reduced their substance use did not differ significantly from women with no or light use in their rates of using aid or being detached, they faced an increased likelihood of losing health insurance. Women who reduced substance use were more likely to lose health insurance than those with light or no substance use (38% versus 16%; p=.008). Given the chronic, relapsing nature of substance use disorders, these health insurance findings are alarming. Also of concern, though less surprising, women with moderate or heavy substance use were less likely to gain insurance coverage between the two interviews, compared with women with light or no substance use (34% versus 63%, p=.020).

|

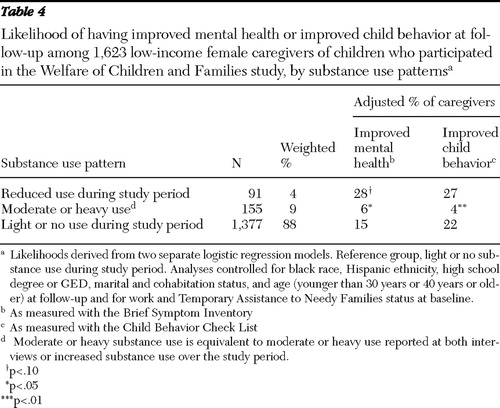

The well-being measures of caregivers and children changed as expected ( Table 4 ). Among caregivers who reduced substance use, BSI scores improved for 28%, compared with 15% of women with light or no use, although this finding was only borderline significant (p=.070). Similarly, 27% of the children living with caregivers who reduced substance use experienced improvements in the CBCL scores, compared with 22% of the children living with caregivers with light or no substance use. This difference was not statistically significant (p=.64), but it highlights that children cared for by women who reduced substance use had outcomes that compared favorably to children of women reporting no or light substance use. Compared with women with light or no substance use, women with moderate or heavy substance use were significantly less likely to experience improvements in BSI scores (6% versus 15%, p=.046), and their children likewise had low rates of improvement in CBCL scores (4% versus 22%, p<.001).

|

Discussion

Among low-income women caring for children in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio between 1999 and 2001, women with moderate or heavy substance use (that is, increased substance use over the study period or moderate to heavy substance use in both interviews) were less likely than women with reduced substance use over the study period and women with light or no substance use during the study period to achieve self-sufficiency goals, such as working or exiting public programs. In contrast, women who reduced substance use over the study period had rates of working and public program use that mirrored those of women who had light or no substance use. Although many have argued that the economic gains to drug treatment come from increasing employment among the treated ( 34 ), there is little evidence regarding work outcomes following treatment, and existing evidence is mixed at best ( 13 , 14 ). In this setting of female caregivers, we found that reduction of substance use accompanies work and public program use patterns that parallel those of women with light or no substance use.

Our findings are salient in light of ongoing changes following the landmark Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996. The PRWORA replaced the entitlement program Aid to Families With Dependent Children with TANF, a series of block grants to states with the goals of increasing work participation, increasing self-sufficiency, and lowering welfare caseloads. Toward these goals, PRWORA imposed 60-month lifetime limits on the receipt of income assistance through TANF and required TANF recipients to work in exchange for benefits.

In this environment, states' treatment of women with behavioral health issues varied widely. In some cases, mental health or substance abuse treatment counted toward work requirements or women in treatment were exempt from requirements. In contrast, other states performed no mental health assessments and treatment activity had no impact on work requirements. In this highly variable environment, welfare caseloads plummeted by 60% from 1995 to 2000 and have remained low since then, employment among single mothers rose, and poverty in single female-headed households has been stable. These changes led many to declare welfare reform a success ( 35 , 36 ), although there is virtual consensus that strong economic conditions during the late 1990s played an important role in raising employment among women ( 36 ). Although data for women with mental or substance use disorders are limited, women with mental and substance use disorders were relatively more likely than other TANF recipients to retain benefits after enactment of PRWORA, to move into work more slowly, and to be sanctioned ( 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ).

In June 2006 the reauthorization of TANF effectively increased the number of TANF recipients who must work and the weekly hours of work activity expected from program recipients. Other changes were also made that are likely to affect women with substance use disorders. Most notably, the reauthorization severely limits states' ability to count behavioral health treatment activity toward work requirements, thus creating additional pressure to work combined with additional barriers to substance abuse treatment among low-income women with substance use disorders. Prior studies with a disproportionate number of male participants may not be applicable for debates about how potential TANF recipients, among whom 90% are female caregivers, are likely to fare under TANF's new stricter work requirements and limitations on access to treatment. Our findings suggest that declining substance use or light or no substance use coincide with more work and less reliance on public programs, compared with moderate or heavy substance use.

We found that caregivers with reduced substance use were more likely than caregivers with light or no substance use to show improved mental health over the study period, although these findings were only borderline significant (p<.10), and that both groups reported similar improvements in the behavior of their children over the study period. In contrast, caregivers with moderate or heavy substance use were significantly less likely to report improvements in their own mental health or their children's behavior, compared with women with light or no substance use. These findings are consistent with the notion that self-sufficiency and good mental health can be complementary goals. This echoes the assertions of the literature on supported work programs for individuals with severe mental disorders ( 42 ). However, women who reduced substance use were significantly more likely to lose health insurance, compared with women with light or no substance use. This setback can pose a threat among former heavy substance users who may require treatment services in order to consolidate the gains they have made and decrease the possibility of relapse. Research demonstrates that retention in treatment is associated with abstinence over time, and this may be especially true for women ( 6 ).

Our findings together suggest caution as states implement new, stricter TANF regulations since its 2006 reauthorization. Women who reduced substance use through any means had economic and well-being outcomes that did not differ significantly from caregivers reporting light or no substance use. Regulations that prevent states from counting mental health and substance abuse treatment toward work requirements will more likely impede access to substance abuse treatment, subsequently shrinking the number of women who successfully reduce substance use.

Our results should be viewed in light of several limitations. First, we had no information on treatment. We, therefore, do not know whether decreases in substance use during the study period were accomplished with or without treatment or what types of treatment services might have been utilized. We also do not know whether women whose substance use increased or remained the same engaged in treatment services. Our research, however, builds on the few previous treatment studies that demonstrate increased employment after treatment ( 3 ). Our findings demonstrate that within an economically disadvantaged female population, decreases in substance use were associated with positive work and income assistance outcomes, in contrast to negative outcomes documented among women with moderate or heavy substance use.

Second, our observational data do not allow us to clearly establish the timing of events, such as changes in substance use patterns, work status, or program use. Thus our results present associations rather than establishing causal relationships between substance use patterns and self-sufficiency or well-being outcomes.

Third, because we had data on relatively few women with moderate to heavy substance use, we were unable to break out effects for women based on alcohol, marijuana, or illicit drug use. There is considerable evidence of the telescoping course of both alcohol use disorders and drug use disorders on the social and medical consequences for women. In addition, among substance-abusing mothers whose children were referred to child welfare services, 68% of children had mothers who abused either alcohol or drugs and 37% had mothers who abused both ( 43 ). However, because of limited statistical power, we were unable to separately analyze women who reported moderate or heavy use in both interviews and those who reported moderate or heavy use only in the follow-up interview.

Fourth, we focused on women caring for children ages zero to four or ten to 14 at baseline; thus our results may not extend to women without children or to men, but instead our findings are intended to fill in gaps in the literature on women and substance use.

Finally, the study relied on self-reports of substance use without validity testing by using urine toxicology or collateral informant reports. However, studies demonstrate that self-report of substance use is likely to be valid when compared with objective measures when participants perceive that there are no adverse consequence to giving valid reports ( 44 ). In a recent treatment study of women with substance abuse, 93% to 97% of self-reports were consistent with urine toxicology ( 6 ). In this survey, if anything, substance use is likely to be underreported and our results are therefore conservative.

Conclusions

Female caregivers with increased substance use fared poorly on measures of well-being and work. Policies that promote, rather than impede, reductions in substance use are more likely to promote self-sufficiency and well-being.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grants DA-10233-06, DA-019485-01, and DA-019855 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by funding from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Network on Mental Health Policy Research. The authors acknowledge Christina Fu, Ph.D., for providing outstanding programming assistance.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. Bethesda, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1999. Available at www.drugabuse.gov/PDF/PODAT/ PODAT.pdfGoogle Scholar

2. Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al: Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 295:2003–2017, 2006Google Scholar

3. Gerstein DR, Datta AR, Ingels JS, et al: NTIES: National Treatment Improvement Evaluation Study: Final Report. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997Google Scholar

4. Project MATCH Research Group: Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 58:7–29, 1997Google Scholar

5. Brady TM, Ashley OS (eds): Women in Substance Abuse Treatment: Results From the Alcohol and Drug Services Study (ADSS). Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2005. Available at www.oas.samhsa.gov/womenTX/wo menTX.pdfGoogle Scholar

6. Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, et al: Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 86:1–21, 2007Google Scholar

7. Grella CE: Services for perinatal women with substance abuse and mental health disorders: the unmet need. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 29:67–78, 1997Google Scholar

8. Montoya ID, Atkinson JS: A synthesis of welfare reform policy and its impact on substance users. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 28:133–146, 2002Google Scholar

9. Women in Substance Abuse Treatment: The DASIS Report. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001Google Scholar

10. Rosen D, Tolman RM, Warner LA: Low-income women's use of substance abuse and mental health services. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 15:206–219, 2004Google Scholar

11. Ettner S, Frank RG, Kessler R: The impact of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 51:64–81, 1997Google Scholar

12. Frank RG, Koss C, Frank RG, et al: Mental Health and Labor Markets Productivity Loss and Restoration: Working Paper No 38. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2005. Available at www.dcp2. org/file/50/wp38.pdfGoogle Scholar

13. Services Research Outcomes Study. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 1998Google Scholar

14. Sindelar JL, Jofre-Bonet M, French MT, et al: Cost-effectiveness analysis of addiction treatment: paradoxes of multiple outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 73:41–50, 2004Google Scholar

15. Marsh JC, Cao D, D'Aunno T: Gender differences in the impact of comprehensive services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 27: 289–300, 2004Google Scholar

16. Clark HW: Residential substance abuse treatment for pregnant and postpartum women and their children: treatment and policy implications. Child Welfare 80: 179–198, 2001Google Scholar

17. Connors N, Grant A, Crone C, et al: Substance abuse treatment for mothers: treatment outcomes and the impact of length of stay. Journal of Substance Abuse and Treatment 31:447–456, 2006Google Scholar

18. Metsch LR, Wolfe HP, Fewell RR, et al: Treating substance-using women and their children in public housing. Child Welfare 80:199–220, 2001Google Scholar

19. McMahon TJ, Winkel JD, Luthar SS, et al: Looking for Poppa: parenting status of men versus women seeking drug abuse treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 31:79–91, 2005Google Scholar

20. Becker GS: Human Capital. New York, Columbia University Press, 1964Google Scholar

21. Grossman M: On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. Journal of Political Economy 80:223–255, 1972Google Scholar

22. Winston P, Angel R, Burton L, et al: Welfare, Children, and Families: A Three City Study: Overview and Design. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999Google Scholar

23. Arria AM, Fuller C, Strathdee SA, et al: Drug dependence among young recently initiated injection drug users. Journal of Drug Issues 32:1089–1102, 2002Google Scholar

24. Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC: Estimating substance abuse treatment need from NHSDA, in Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods of the American Statistical Association, 1994. Alexandria, Va, American Statistical Association, 1994Google Scholar

25. Gavin DR, Ross HE, Skinner HA: Diagnostic validity of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in the assessment of DSM-III drug disorders. British Journal of Addiction 84: 301–307, 1989Google Scholar

26. Claussen B, Aasland OG: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in a routine health examination of long-term unemployed. Addiction 88:363–368, 1993Google Scholar

27. Conigrave KM, Saunders JB, Reznik RB: Predictive capacity of the AUDIT questionnaire for alcohol-related harm. Addiction 90:1479–1485, 1995Google Scholar

28. Connors NA, Bradley RH, Mansell LW, et al: Children of mothers with serious substance abuse problems: an accumulation of risks. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 30:85–100, 2004Google Scholar

29. Suchman N, Mayes L, Conti J, et al: Rethinking parenting interventions for drug-dependent mothers: from behavior management to fostering emotional bonds. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 27:179–185, 2004Google Scholar

30. Derogatis LR, Derogatis M: SCL-90-R and the Brief Symptom Inventory, in Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Edited by Spilker B. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996Google Scholar

31. Morlan KK, Tan SY: Comparison of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the Brief Symptom Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology 54:885–894, 1998Google Scholar

32. Achenbach TM, Edlebroch C: The Child Behavior Profile: boys 6–11. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 46: 476–488, 1978Google Scholar

33. Achenbach TM, Edlebroch C: The Child Behavior Profile II: boys aged 12–16 and girls aged 6–11 and 12–16. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 47:223–233, 1979Google Scholar

34. Belenko S, Patapis N, French MT: Economic Benefits of Drug Treatment: A Critical Review of the Evidence for Policy Makers. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Treatment Research Institute, 2005Google Scholar

35. Blank R: Evaluating welfare reform in the United States. Journal of Economic Literature 60:1105–1166, 2002Google Scholar

36. Moffitt RA: Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2003Google Scholar

37. Danziger S, Corcoran M, Danziger S, et al: Barriers to the employment of welfare recipients, in Prosperity for All? The Economic Boom and African Americans. Edited by Cherry R, Rodgers W. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 2000Google Scholar

38. Meara E, Frank RG: Welfare Reform, Work Requirements, and Employment Barriers. NBER Working Paper Series. Cambridge, Mass, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2006Google Scholar

39. Montoya ID: Effect of peers on employment and implications for drug treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 31:657–668, 2005Google Scholar

40. Pollack H, Reuter P: Welfare receipt and substance-abuse treatment among low-income mothers: the impact of welfare reform. American Journal of Public Health 96:2024–2031, 2006Google Scholar

41. Morgenstern J, Riordan A, McCrady BS, et al: Specialized Screening Approaches Can Substantially Increase the Identification of Substance Abuse Problems Among Welfare Recipients. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, 2001Google Scholar

42. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire Study of Supported Employment for People With Severe Mental Illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391–399, 1996Google Scholar

43. Jones L: The prevalence and characteristics of substance abusers in a child protective service sample. Journal of Social Work in the Addictions 4:33–50, 2004Google Scholar

44. Weiss RD, Najavits LN, Greenfield SF, et al: Validity of substance use self-reports in dually diagnosed outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:127–128, 1998Google Scholar