Hospitalization for Psychiatric Illness Among Community-Dwelling Elderly Persons in 1992 and 2002

The 1990s saw many changes in the American health policy environment. In a period characterized by the penetration of managed behavioral health care, increased use of psychotropic medication, and tightening of inpatient admissions criteria, a smaller percentage of patients were hospitalized, hospital stays became shorter, and costs declined. However, few studies examined in detail the evolving patterns in the use of inpatient hospital stays for the noninstitutionalized elderly population with psychiatric illnesses and Medicare benefits or compared utilization trends across principal diagnoses. To address this important issue, we conducted an analysis of 1992 and 2002 national Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files, which provide data for every hospital inpatient service reimbursed by Medicare. Our findings update earlier reports on national trends in inpatient service use by elderly persons for treatment of mental illness or substance use disorder ( 1 ).

Methods

Data were compiled from MedPAR records of inpatient hospital claims submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Demographic characteristics and diagnoses of beneficiaries (primary and secondary) were included in the MedPAR files, as were detailed departmental charge data and days of care. Our study population included all senior Medicare beneficiaries in the nation, age 65 or older, enrolled in Medicare Part A throughout the calendar year. We excluded persons with any managed care coverage during the year because Medicare does not receive claims for stays by beneficiaries in capitated plans. Because our study focused on community dwellers, we excluded persons being treated in skilled nursing facilities during the year. The inclusion criteria yielded 26,622,940 beneficiaries in 1992 (mean±SD age 75±7.1 years; sample 60% female and 7% African American) and 25,675,857 in 2002 (age 74±7.2 years; sample 58% female and 8% African American).

Stays were classified as psychiatric hospitalizations if the primary diagnosis was a mental disorder ( ICD-9-CM codes 290–319) other than mental retardation ( ICD-9-CM codes 317–319), dementia (codes 290, 294.1, and 331), or an organic disorder (codes 293.8–294). Medicare expenditures excluded pass-through payments and amounts recovered or rescinded in final settlements. We reported 1992 costs in 2002 dollars using the hospital care component of the personal health care expenditure price index, developed by the CMS Office of the Actuary's National Health Statistics Group. Expenditures are considered a proxy for the quantity and intensity of services, and we adjusted for inflation to make the value of services comparable for both years.

Results

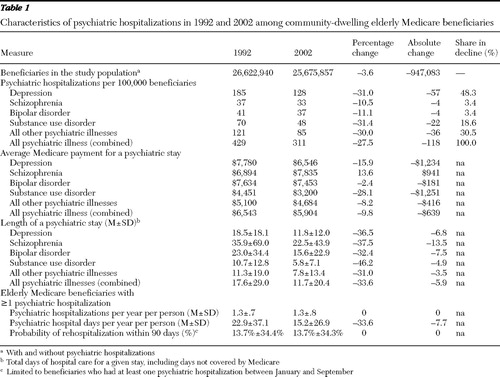

Although Medicare enrollment increased from 1992 to 2002, so did managed care enrollment and nursing home stays. Therefore, the number of beneficiaries that fit our inclusion criteria declined slightly (from 26.6 to 25.7 million). Rates of inpatient hospitalization for psychiatric conditions decreased 28%, from 429 to 311 persons per year per 100,000 eligible beneficiaries ( Table 1 ). Reductions in inpatient stays for depression (57 per 100,000) accounted for almost half (48%) of the absolute decline in rates of psychiatric hospitalization (118 per 100,000). Sharp declines were also observed for substance use disorders and other psychiatric conditions. We observed quite different trends for hospitalizations for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, for which declines were minimal and accounted for less than 7% of the total reduction. [A figure showing the contributions of diagnoses to the decline in psychiatric hospitalizations is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] Sensitivity analyses indicated that unadjusted rates of decline from 1992 to 2002 were statistically equivalent to those adjusted for gender, age, and race.

|

The average length of stay per psychiatric hospitalization declined (from 17.6 to 11.7 days). Among patients who had at least one psychiatric stay, the average number of psychiatric admissions remained flat (at 1.3 hospitalizations per person). Another indicator of recidivism, probability of rehospitalization within 90 days, was similarly unchanged (13.7%).

Declines in length of stay were accompanied by relatively smaller reductions in expenditures per psychiatric stay (10% reduction, from $6,543 to $5,904 per stay). Although lengths of stay declined sharply across all diagnostic subgroups, reductions in expenditures were not uniform. The sharpest declines were for substance use disorders ($1,251 per stay) and depression ($1,234 per stay). Of note, despite much shorter stays than in 1992, expenditures per hospitalization associated with schizophrenia increased in 2002, and Medicare savings were minimal for stays associated with bipolar disorder.

Discussion

Among the nonelderly population, for whom managed care systems became increasingly dominant during the 1990s, increasing restrictions on admission for psychiatric inpatient care and financial pressures to reduce length of stay were widespread during the 1990s ( 2 , 3 ). Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, being generally the most costly psychiatric service, was a natural target for cost-containment efforts ( 2 ). Faced with changes in the role of inpatient hospitalization as a component of care, clinicians developed a treatment philosophy that some commentators have described as an "intensive care" model ( 4 ), such that inpatient stays were considered to be reserved for patients with more acute, severe clinical profiles.

This brief report presents national trends during the same period for psychiatric inpatient care provided to the community-dwelling elderly Medicare population that receives traditional fee-for-service care. We observed a 28% decline in psychiatric hospitalization rates. Epidemiological studies, however, did not report declines in the prevalence of mental disorders ( 5 ) during the same period. Although our study population received benefits on a fee-for-service basis, cost-containment efforts from managed care may have had spillover effects, because inpatient service models had adopted care patterns at the unit or hospital level.

Declines in psychiatric admissions mostly resulted from reductions for conditions other than schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, particularly for depression and substance use disorder. Changes in admission rates for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were flat. The decrease in admissions for depression or substance use disorder fits with an intensive care treatment model (for example, admit patients with depression only when gross dysfunction or active risk of suicide is observed, or admit patients for detoxification only when a less intensive level of care is potentially unsafe). Unlike hospitalization for depression and substance use disorder, it is possible that admissions and stays for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia were more difficult to limit because of more severe disease manifestations (such as acute psychosis and lack of behavioral control) and patient characteristics (such as more limited family and social network supports and limited housing and discharge options).

Lower rates of hospital treatment for depression coincided with dramatic increases in rates of outpatient depression diagnosis and antidepressant use ( 6 ). Expanded outpatient treatment of depression might have reduced the need for inpatient care. Tests of such hypotheses should be pursued in longitudinal studies that incorporate data from the entire continuum of care, including outpatient pharmacy use and data on disease severity.

Notably, despite the reduced length of hospital stays, we did not observe increases in psychiatric rehospitalization rates. Institutionally based studies have suggested that shorter stays might produce more readmissions ( 7 ). Policy makers can note that the feared revolving-door rehospitalizations were not observed in aggregate terms (however, adequate assessment of a revolving-door hypothesis requires evaluation of a broader array of patient-level outcomes). Stable rehospitalization rates, despite dramatic declines in average lengths of stay, may be partially attributable to the fact that the decline in inflation-adjusted expenditures were on a smaller scale (10%), which serves as a proxy measure for the intensity of services.

Medicare's share in the overall financing of care for mental illness and substance use disorders expanded considerably during the period in question ( 8 ), and MedPAR files provided important data regarding inpatient psychiatric care for almost the entire population of community-dwelling elderly Medicare beneficiaries. MedPAR data from 1992 and 2002 allowed direct comparisons of the operation of this component of psychiatric care at two time points divided by a period of dramatic restructuring of the mental illness and substance use disorder care sector. Despite the strong external validity of MedPAR data, they have important limitations. For example, inpatient stays are documented, but other components of care, such as outpatient care, cannot be examined. Also, these data cannot support causal inferences as to the factors driving these trends. Further research using other data sources is needed to explore the causes of these changes.

Conclusions

We documented major contrasts between the nationwide profiles of inpatient psychiatric care for the elderly in 1992 and 2002. The period between these two years, for mental health care in general, saw aggressive public and private efforts to restructure inpatient utilization patterns to constrain expenditures, along with development of contemporary intensive care models of inpatient psychiatric care ( 4 ). Although fee-for-service Medicare hospitalizations were not subject to as many restrictions, such as prior-authorization requirements, as those paid for by private managed care plans, they experienced substantial declines in incidence, length of stay, and Medicare expenditures per stay, which were not accompanied by increased rates of readmission.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant MH-60831 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by cooperative agreement HS016097 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Cano C, Hennessy KD, Warren JL, et al: Medicare Part A utilization and expenditures for psychiatric services: 1995. Health Care Financing Review 18:177–193, 1997Google Scholar

2. Mechanic D: Mental Health and Social Policy: The Emergence of Managed Care, 4th ed. Needham Heights, Mass, Allyn and Bacon, 1999Google Scholar

3. Bao Y, Sturm R: How do trends for behavioral health inpatient care differ from medical inpatient care in US community hospitals? Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 4:55–63, 2001Google Scholar

4. Glick ID, Carter WG, Tandon R: A paradigm for treatment of inpatient psychiatric disorders: from asylum to intensive care. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 9:395–402, 2003Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515–2523, 2005Google Scholar

6. Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly Medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51:1718–1728, 2003Google Scholar

7. Heeren O, Dixon L, Gavirneni S: The association between decreasing length of stay and readmission rate on a psychogeriatric unit. Psychiatric Services 53:76–79, 2002Google Scholar

8. Frank RG, Glied S: Changes in mental health financing since 1971: implications for policymakers and patients. Health Affairs 25:601–613, 2006Google Scholar