Social Functioning of Patients With Personality Disorder in Secondary Care

With better methods of identifying personality disorders it is becoming increasingly apparent that personality disorder in secondary health care is a significant clinical issue. Studies have indicated that over half of patients seen in community mental health services have a personality disorder when formally assessed ( 1 ). This proportion increases to up to 90% of patients in specialist teams such as those concerned with assertive outreach ( 2 ). Despite these facts, personality disorder is often poorly recognized, and it is likely that underdiagnosis prevents effective management strategies from being implemented. Although the standard conceptual view of personality as having distinct categories of disorder is challenged from several sources ( 3 , 4 ), there is widespread agreement that, however it is measured, personality pathology creates additional psychopathology, difficulties in management, and social dysfunction ( 5 , 6 ). The difficulties include the basic maintenance of accommodation, nutrition, safety, and self-care, as well as the ability to interact successfully with others.

Measures of social dysfunction are well established; they record problems in interpersonal functioning and an inability to manage optimally within current social structures ( 7 ). What is not clear is how this dysfunction affects the day-to-day running of specialist psychiatric services. It might be expected that increased severity of personality problems would lead to an increase in social dysfunction because personality disorder impairs the ability of people not only to function within a social context but also to seek help effectively. This has led some experts to advocate for assessing personality pathology with a severity approach rather than with the potentially unstable categorical system in use ( 8 ). The social dysfunction in combination with the difficulties in seeking help has the potential to lead to greater problems than the impact of any axis I disorder, thus increasing the need for community teams to recognize and manage this problem more effectively. This is in part a result of the configuration of services, primarily aimed toward axis I disorder.

A major problem with the management of social dysfunction among persons with personality disorder is the difficulty that such patients have in accessing the normal structures that might be able to assist them in society. These difficulties suggest that other strategies need to be provided to maximize function and quality of life. Although pharmacological and psychological interventions are available ( 9 , 10 ), the former has a limited evidence base and the latter is rarely used outside of a research setting. For many patients and clinicians, the management of personality disorder is as likely to focus on broader social, environmental, and contextual issues in the relief of primary symptoms ( 11 ). This can only be done if personality disorder is recognized adequately and a clear understanding of its impact on functioning is reached.

The purpose of this study was to test the null hypothesis that severity of personality disorder does not affect the objective or subjective social functioning of patients in a psychiatric secondary care setting.

Methods

Sample

Data were collected between January 2001 and February 2002 in four urban centers in England as part of a large survey examining drug or alcohol problems co-occurring with psychiatric problems among patients served by both community mental health teams and alcohol and drug services ( 12 ). The methodology of the data collection is described fully elsewhere ( 12 ). Briefly, a two-phase methodology was used. In phase 1 a caseload census identified the sampling frame of all patients receiving psychiatric services. All key workers were identified and sent a questionnaire to complete. In phase 2, a total of 400 patients were selected at random to be interviewed. All four of the community mental health teams studied conformed to the accepted definition of a community team ( 13 ). All patients were under the care of a consultant psychiatrist and had a care coordinator assigned to them. The interview sample represented psychiatric patients in a secondary urban care setting. Ethical approval for the collection of data was provided by the local research ethics committee covering each of the four study centers. After complete description of the study to the participants, written informed consent was obtained.

Assessments

Assessments of both axis I and axis II diagnoses were completed as well as those for axis V (social functioning). The axis I diagnosis was obtained from preliminary data provided by key workers and confirmed with Operational Criteria for Diagnosis ( 14 ) on the basis of review of case notes. Depressive symptoms were measured with the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale ( 15 ), anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Brief Scale for Anxiety ( 16 ), and total psychopathology was assessed with the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale ( 17 ). Axis II diagnoses were determined with the Quick Personality Assessment Schedule (PAS-Q) ( 18 ), a rapid and easily applied form of the personality schedule ( 19 ) that allows for categorical and cluster diagnosis of personality disorder. Because there is some debate about the relative value of individual diagnosis, severity of personality disorder was also derived from the PAS-Q according to the method of Tyrer and Johnson ( 20 ). All of these tools were used to assess the impact of personality function on social functioning.

Social functioning was assessed in two ways. First, an objective measure of social need was obtained with the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) ( 21 ). It measures the objective needs of patients across 22 domains. The scores indicate whether a need is met, partially met, or unmet, and a larger score indicates a greater level of unmet need. The Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ) ( 22 ) was used to provide a subjective assessment of social functioning from the patient's perspective. It measures eight domains of social functioning on a Likert 4-point scale and gives a total score between 0 and 24, with higher scores indicating worse social functioning.

Statistical analysis

The data set was analyzed with SPSS, version 14.0. This program was used to correlate personality disturbance and its severity with factors associated with social function. Spearman's rho and the Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess simple correlations between personality disorder, severity of the disorder, axis I disorder, and social outcome as measured by the CAN and SFQ. Regression modeling was used to account for potential confounding between axis I and axis II diagnoses. The statistical assumptions of linear regression modeling were assessed, and the data set conformed to them. Because of the nature of descriptive studies and the large data set available to examine, the risk of a type I error was overcome by using predetermined criteria for analysis and clustering personality disorder into clinically relevant groups (clusters A, B, and C in DSM-IV ). Statistical significance at the p=.01 level was required to further minimize type I error because most data analysis did not allow for statistical correcting (with Bonferroni or other similar methods).

Results

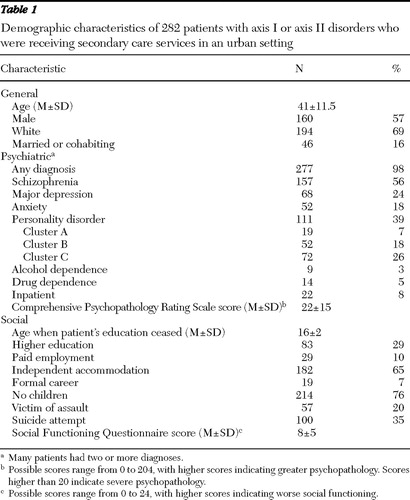

The caseload census revealed 2,566 current patients (phase 1). All key workers were sent a questionnaire to complete; the response rate was 99% (N=2,528). In phase 2, a total of 400 of these patients were selected at random to be interviewed. A total of 282 patients (71%) agreed to be interviewed. The major reason for nonresponse was refusal by 66 patients (17%). The interviewed patients were included in this analysis. The general demographic data are shown in Table 1 . All participants except five (2%) had at least one psychiatric diagnosis, and there was significant overlap between axis I and axis II disorders. Thirty-nine percent of patients had a diagnosis of a personality disorder, and many had two or more personality disorders. The most common axis I diagnosis was schizophrenia (56%), and almost one in four patients was diagnosed as having major depression (24%). The sample was predominantly white (69%), and participants were living in their own accommodation (65%). Employment was uncommon, with 10% of patients in paid employment. Only 7% had a formal career.

|

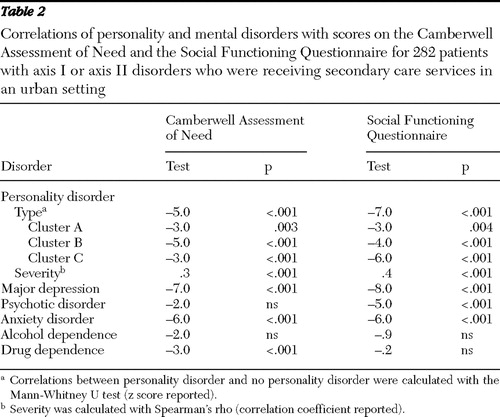

There was a close correlation between social dysfunction, social need, and axis II diagnosis ( Table 2 ). This correlation was significant across personality disorder clusters A, B, and C. This strong correlation was not found with all axis I disorders. The presence of a psychotic disorder did not have an independent effect on objective social functioning, and a diagnosis of a drug disorder was also not significant for subjective functioning. A diagnosis of alcohol use disorder was not related to social dysfunction on any measure.

|

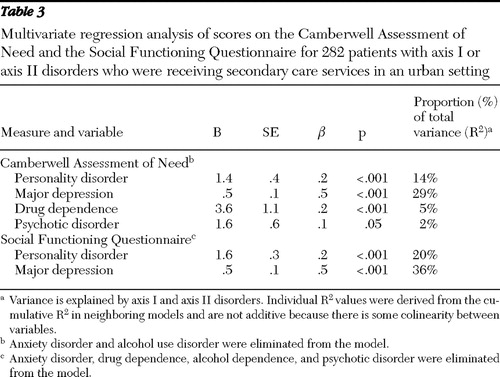

Because of the potential overlap between diagnoses and the high comorbidity of personality disorders in this sample, we used regression modeling (both individual linear and multiple stepwise modeling) to assess the independent impact of the various diagnoses on social dysfunction. This approach allowed for estimation of the individual variance of axis I and II diagnoses on social dysfunction as well as of the combined impact of overall morbidity. We performed parallel analysis of the CAN and SFQ data to provide the most comprehensive analysis. The axis I diagnoses of psychotic disorder, depression, anxiety disorder, and alcohol dependence and drug dependence were included in this model together with severity of personality disorder ( Table 3 ).

|

The nature of an axis I or axis II diagnosis accounted for less than half of the variance for each of these social dysfunction measures. However, both measures also showed that the greatest degree of variance was accounted for by the diagnosis of depression and more severe personality disorder. The CAN showed a small but significantly independent effect for the presence of a drug use diagnosis or psychotic disorder, but neither model showed an independent effect of social dysfunction by alcohol diagnosis or anxiety disorder. Both models also showed a degree of colinearity between the diagnoses of personality disorder and axis I disorder, suggesting that comorbid disorders contributed to worse social dysfunction.

Discussion

This study attempted to dissect the impact of mental and personality disorders on the individual patient's ability to integrate fully with the social environment. Results showed that both major depression and personality disorder had a significant negative impact on social functioning, whereas the effects of other axis I disorders generally became insignificant when these factors were taken into account. There are several possible explanations for these findings: the disorders with no significant association may have little impact on social function, or the disorders with no significant association may create social dysfunction only when co-occurring with personality disorder, or the psychiatric disorder itself may minimize the patient's insight as to social need (and possibly that of an objective observer) when need in fact exists, or the findings may simply be due to chance.

The possibility of a chance finding is unlikely but cannot be completely dismissed. Although the danger of a type I error was minimized by limiting the number of analyses, testing a priori hypotheses, and increasing the level of significance to p=.01, there remains the possibility that some of the significant associations could have occurred by chance. Similarly, the possibility that many axis I disorders have no social impact whatsoever is highly unlikely. Individual correlations of diagnosis and social functioning suggest that there was an association between axis I disorder and social dysfunction. The literature supports the presumed negative impact of alcohol use disorders ( 23 ), anxiety disorders ( 24 ), psychotic disorders ( 25 ), and drug use disorders ( 26 ) in patients' lives. This study's findings highlight that this association is also true of personality disorders, whether measured globally, by diagnostic clusters, or by severity. Although some psychiatric disorders may diminish the ability of a patient to understand the extent to which his or her disorder, particularly chronic psychosis, contributes to social dysfunction, the structure of the CAN compensates for this by including objective measures carried out by key workers. Regression modeling of the impact of mental disorder on the CAN scores compared with the SFQ scores indeed showed a broader range of effects of mental disorder, although both alcohol use disorders and anxiety disorders had no significant impact in this analysis.

Because these data are based on a cross-sectional survey, they provide associative information only, a "snapshot" of the association between personality disorder, axis I disorder, and social functioning. No formal treatment for personality disorder was given, and all participants received only standard community treatment. Although these limitations mean that caution is needed in interpreting the results, they also represent a pragmatic picture of personality disorder and its effects in standard, everyday practice.

Our interpretation of these findings is that the social dysfunction associated with alcohol and drug use disorders, psychosis, and anxiety disorders is generally well recognized by community mental health teams, and its impact is likely to be minimized. However, the social consequences of depression and personality disorder are more resistant to standard care. Chronic depression (which may be a reflection of depression and comorbid personality disorder in which the personality disorder is unrecognized) is difficult to manage effectively and is associated with deterioration of social function ( 27 ). This may also be true of personality pathology and may contribute to difficulties with interpersonal engagement and pervasive problems in integrating into a community. The evidence of colinearity of these diagnoses (comorbidity with each component exerting an independent downward effect) is in line with recent reviews showing that the outcome in depression with personality disorder is worse than that of depression alone ( 28 ).

Conclusions

The results of this study stress the importance of effective recognition and management of personality disorders because they are significantly associated with social dysfunction. They further highlight the independent contributions of personality disorder and depression to social dysfunction when both disorders are present and gives additional reasons why personality status should not be ignored. Despite the focus on axis I disorders in specialist psychiatric care, social dysfunction remains a problem in depression, particularly in the presence of comorbid personality pathology. The findings also suggest that novel approaches to improving social functioning by addressing the needs of patients with personality disorder would be an appropriate way forward. Although several approaches are available ( 29 , 30 , 31 ), the ideal application for each remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant 1217194 from the English Department of Health's Drug Misuse Research Initiative. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the sponsors.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Keown P, Holloway F, Kuipers E: The prevalence of personality disorders, psychotic disorders and affective disorders amongst the patients seen by a community mental health team in London. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37: 225–229, 2002Google Scholar

2. Ranger M, Methuen C, Rutter D, et al: Prevalence of personality disorder in the case-load of an inner-city assertive outreach team. Psychiatric Bulletin 28:441–443, 2004Google Scholar

3. Western D: Divergences between clinical and research methods for assessing personality disorders: implications for research and the evolution of axis II. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:895–903, 1997Google Scholar

4. Livesley WJ: A framework for integrating dimensional and categorical classifications of personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 21:199–224, 2007Google Scholar

5. Grant B, Hasin D, Stinson, D et al: Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:948–958, 2004Google Scholar

6. Coid J, Yang M, Tyrer P, et al: Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:423–431, 2006Google Scholar

7. Bradshaw J: A taxonomy of social need, in Problems and Progress in Medical Care, 7th series. Edited by McLachlan O. London, Oxford University Press, 1987Google Scholar

8. Seivewright H, Tyrer P, Johnson T: Changes in personality status in neurotic disorder. Lancet 359:2253–2254, 2002Google Scholar

9. Tyrer P, Newton-Howes G: Rational prescribing in personality disorders. Psychiatry 4:11–14, 2005Google Scholar

10. Bateman A, Zanarini M: Personality disorders, in The Cambridge Textbook of Effective Treatments in Psychiatry. Edited by Tyrer P, Silk KR. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 2007Google Scholar

11. Tyrer P: Nidotherapy: a new approach to the treatment of personality disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 105:469–471, 2002Google Scholar

12. Weaver T, Madden P, Charles V, et al: Comorbidity of substance misuse and mental illness in community mental health and substance misuse services. British Journal of Psychiatry 183:304–313, 2003Google Scholar

13. Malone D, Newton-Howes G, Simmonds S, et al: Community mental health teams (CMHTs) for people with severe mental illnesses and disordered personality. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD000270, 2007Google Scholar

14. McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I: A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychiatric illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:764–770, 1991Google Scholar

15. Montgomery S, Asberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry 134: 382–389, 1979Google Scholar

16. Tyrer P, Owen R, Cicchetti D, The Brief Scale for Anxiety: a subdivision of the Comprehensive Psychopathology Rating Scale. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 47:970–975, 1984Google Scholar

17. Asberg M, Montgomery S, Perris C, et al: A Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 271: 5–27, 1978Google Scholar

18. Tyrer P: Quick Personality Assessment Schedule: PAS-Q, in Personality Disorders: Diagnosis, Management and Course, 2nd ed. Edited by Tyrer P. London, Arnold, 2000Google Scholar

19. Tyrer P, Alexander MS, Cicchetti D, et al: Reliability of a schedule for rating personality disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 135:168–174, 1979Google Scholar

20. Tyrer P, Johnson T: Establishing the severity of personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1593–1597, 1996Google Scholar

21. Phelan M, Slade M, Thornicroft G, et al: The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN): the validity and reliability of an instrument to assess the needs of people with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:589–595, 1995Google Scholar

22. Tyrer P, Nur U, Crawford M, et al: The Social Functioning Questionnaire: a rapid and robust measure of perceived functioning. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 51:265–275, 2005Google Scholar

23. Devlin N, Scuffham P, Bunt L: The social costs of alcohol abuse in New Zealand. Addiction 92:1491–1506, 1997Google Scholar

24. Kessler R, Foster C, Saunders W, et al: Social consequences of psychiatric disorders: I. educational attainment. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1026–1032, 1995Google Scholar

25. Hafner H, Loffler W, Maurer K, et al: Depression, negative symptoms, social stagnation and social decline in early schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia 100:105–118, 1999Google Scholar

26. Gossop M: Treating Drug Misuse Problems: Evidence of Effectiveness. London, Department of Health, National Treatment Agency, 2006Google Scholar

27. George L, Blazer D, Hughes D: Social support and the outcome of major depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 154:478–485, 1989Google Scholar

28. Newton-Howes G, Tyrer P, Johnson T: Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: a meta-analysis of published studies. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:13–20, 2006Google Scholar

29. Tyrer P, Bajaj P: Nidotherapy: making the environment do the therapeutic work. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 11:232–238, 2005Google Scholar

30. Ryle A: The contribution of cognitive analytic therapy to the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 18:3–35, 2004Google Scholar

31. Huband N, McMurran M, Evans C, et al: Social problem-solving plus psychoeducation for adults with personality disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 190:307–313, 2007Google Scholar