Datapoints: Polypharmacy as the Initial Second-Generation Antipsychotic Treatment

Antipsychotic polypharmacy is a debatable practice that continues to occur. Evidence suggests that the likelihood of having a physician office visit that involves antipsychotic polypharmacy may have increased 2.5 times from 1993–1994 to 1999–2000 ( 1 ). This is concerning because use of second-generation antipsychotics has largely replaced that of first-generation antipsychotics ( 2 ), and the number of office visits resulting in an antipsychotic prescription has increased 1.9 times from 1998 to 2002 ( 3 ). Although there is agreement that polypharmacy is generally not recommended, we found few studies that describe when concomitant antipsychotic use might start.

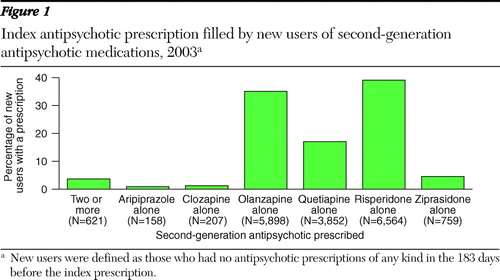

To explore the use of multiple antipsychotics as a first-line treatment, we examined California's Medicaid claims data to identify all beneficiaries who filled at least one prescription for a second-generation antipsychotic in 2003. We defined new users as those who had no antipsychotics of any kind in the 183 days before the index prescription. We defined polypharmacy as those with two or more second-generation antipsychotic prescriptions on the date of initiation.

Among the 238,550 persons who filled prescriptions for second-generation antipsychotics, 7.0% were considered to be new users of this class. New users were evenly distributed by age, with 38.2% aged 35–54 years. Half were female (51.4%), 45.7% were Caucasian, 17.5% were African American, 17.6% were Hispanic, 11.6% were from another race, and the race was unknown for 7.5%.

A total of 3.7% of new users filled a prescription for multiple second-generation antipsychotics. Most users initiated treatment with one second-generation prescription, such as risperidone (39.1%) or olanzapine (35.1%) ( Figure 1 ).

Our results should be interpreted cautiously, because we defined new users as those with no antipsychotic prescriptions of any kind in the six months before the index claim. Some patients may not truly be new users and may have had success with polypharmacy at some time in the past. Given these limitations, our findings suggest that antipsychotic polypharmacy may be starting earlier than expected. It is difficult to understand why multiple antipsychotics would be prescribed without a trial of a single agent. We suspect that some physicians may favor multiple antipsychotics as a practice to offset the side effects of the other more potent antipsychotic agents. More studies are needed to examine second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank Patrick Finley, Pharm.D., Paul Perry, Ph.D., Gregory Doe, Pharm.D., and Anura Ratnasiri, M.S., for their contributions. The views expressed in this column are for information and discussion and may not represent the formal policies of the California Department of Public Health or the California Department of Health Care Services. Responsibility for the text and the positions implied in it rest solely with the authors.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Botts S, Hines H, Littrell R: Antipsychotic polypharmacy in the ambulatory care setting, 1993–2000. Psychiatric Services 54:8, 2003Google Scholar

2. Stahl SM: Selecting an atypical antipsychotic by combining clinical experience with guidelines from clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:31–41, 1999Google Scholar

3. Aparasu R, Bhatara V, Gupta S: US national trends in the use of antipsychotics during office visits, 1998–2002. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 17:147–152, 2005Google Scholar