A Disease Management Program for Families of Persons in Hong Kong With Dementia

The adverse psychosocial health effects in caring for family members with dementia are recognized, and different types of psychosocial interventions have provided preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of these interventions on improving family caregivers' mental health and delaying the institutionalization of persons with dementia ( 1 ). Yet there are several limitations of recent studies of interventions for family members of persons with dementia, including the paucity of controlled trials of needs-based interventions with a broad range of outcome measures and sufficient study power, poor adherence to published dementia care guidelines, and the finding that most models of intervention involved limited collaborations between health care professionals and families of persons with dementia ( 2 , 3 ).

Some integrated multidisciplinary and multicomponent educational programs, such as the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH) and the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) programs in the United States ( 1 , 4 ), that consist of multiple helping strategies, including information giving, stress management, and problem-solving skills, reported significant impacts on families' management of patients' problem behaviors and families' general health. But few have shown a long-term effect on improving caregivers' mental health or quality of life ( 2 ). In addition, most studies have focused on Caucasian populations, and only a few have focused on Asian populations, where great importance is attached to intimate interpersonal relationships and interactions with family members ( 1 ). In an attempt to address such gaps in the quality of dementia care, our trial tested the effects of an interdisciplinary, community-based dementia care management program for Chinese families of persons with dementia on caregivers' and patients' psychosocial functioning.

Methods

This controlled trial was conducted between January 2005 and September 2006 with a repeated-measures design. It was approved by the research ethics committees of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and of the two dementia resource centers in Hong Kong. A total of 88 of 200 pairs of eligible patients and their primary caregivers were selected randomly from a list of patients who attended one of the two dementia centers. On the basis of previous studies in Western and Chinese populations ( 2 , 5 ), this sample size could detect any significant difference between groups at a 5% significance level, with a power of 90% and 15% of potential attrition ( 6 ).

The inclusion criteria for family caregivers included being 18 years or older and living with and caring for a relative who was diagnosed as having a type of dementia caused by Alzheimer's disease, according to DSM-IV criteria ( 7 ). Caregivers who had mental illness themselves or who had cared for their family member for less than three months were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained after the procedures had been fully explained. With their consent, the families were assigned randomly either to routine dementia care or to the dementia care management program.

The dementia care management program is an education and support group for family members that lasted for six months. A multidisciplinary committee—including a psychiatrist, a social worker, a case manager (nurse) from each center, and the researchers—selected 25 intervention objectives from the recommended dementia guidelines established in the United States ( 1 , 8 ) and designed an information and psychological support system linking case managers and dementia care services, health professionals, and referrals. One key component was the case managers who received 32 hours of formal training by the researchers and coordinated all levels of family care according to the results of a structured needs assessment ( 5 ). Each family was assigned one case manager who together with another nurse in the center, summarized the assessment data and, in collaboration with the caregivers, prioritized problem areas and formulated a multidisciplinary education program for each family on effective dementia care—for example, cognitive stimulation.

The program consisted of 12 sessions that were held every other week and lasted two hours each. It consisted of five phases—orientation to dementia care (one session), educational workshop about dementia care (three sessions), family role and strength rebuilding (six sessions), community support resources (one session), and review of program and evaluation (one session)—that were based on the family programs by Belle and colleagues ( 1 ) and Fung and Chien ( 5 ). The program content was selected on the basis of the results of the family needs assessments. For example, two families who found dementia caregiving very difficult were helped in multiple ways: they were provided information, problem-solving skills training, and stress management techniques. The program also used a culturally sensitive family intervention model, and many of the Chinese cultural tenets (for example, valuing collectivism over individualism and emphasizing filial obligation and family and kinship ties) were considered in respect to family relationships and value orientation during the program. The case managers also conducted home visits and brief education about dementia care every other week and family health assessment once per month.

Both centers provided both groups with routine dementia care, such as pharmacotherapy and social and recreational activities for the patients and written educational materials about dementia care for the caregivers. In order to conceal the intervention of interest for family caregivers, six monthly education sessions on dementia care were provided to the standard care group.

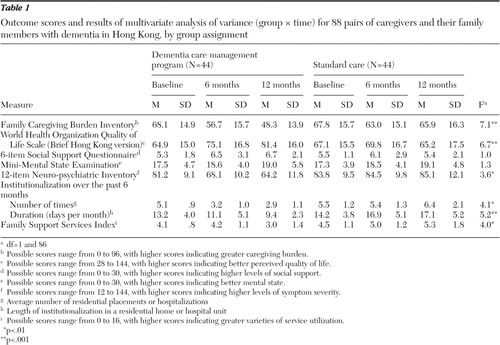

One researcher who was blind to the group assignment administered the pretest before randomization and the two posttests at six and 12 months after the start of the intervention. Outcome measures including caregivers' burden, quality of life, and social support were rated by using, respectively, the Chinese version of the Family Caregiving Burden Inventory ( 9 ), the World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale ( 10 ), and the six-item Social Support Questionnaire ( 11 ). The patients' symptom severity was assessed by using the Neuro-psychiatric Inventory ( 12 ) and the Mini-Mental State Examination ( 13 ). The amount of community services was assessed by using the Family Support Services Index ( 14 ) and the frequency and length (days per month) of institutional placements in the previous six months. Scoring information for the outcome measures is presented in Table 1 . Repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed for the outcome variables to determine the treatment effects, followed by post hoc Tukey's honestly significant difference analysis (that is, protected type I error). The data analysis used an intention-to-treat design that maintained the advantages of random allocation ( 15 ). In this study, one participant in the standard care group whose relative with dementia died at the six-month posttest and two intervention group participants who failed to complete the program still remained in the study group. They were asked to complete the outcome measures at the posttests, and these data were included in the data analysis.

|

Results

The mean age of the 88 caregivers was 43.6±9.2 years (range=34–65), and 60 (68%) had completed secondary school. Their average monthly household income was U.S. $1,538. Fifty-six caregivers were female (64%). Thirty-two (36%) were children of the person with dementia, and 28 (32%) were spouses. The mean age of the 88 patients was 67.8±6.8 years (range=64–79), and their average duration of illness was 2.8±1.5 years. Fifty of them (57%) were male. Forty-eight (55%) received cholinesterase inhibitors (for example, donepezil) or N -methyl- d -aspartate antagonists (for example, memantine), and 55 (63%) received a low dosage of antipsychotic medications.

The average amount of caregiving was 5.2±.8 hours per day (range=3.1–8.3). Seventy of the patients (80%) were at the early (ambulatory) stage of dementia and presented low to moderate levels of impairments in activities of daily living, such as bathing, communication, and toileting ( 7 , 8 ), and 18 (20%) were at the late stage.

There were no differences between the study groups with respect to their sociodemographic characteristics, types and dosages of medications, or mean scores on the baseline measures when Student's t tests or chi square tests were used. Forty-two (95%) of the families completed the dementia care program, and one family member in the control group could not be contacted at the 12-month follow-up.

There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups on the MANOVA for the outcome variables (F=4.8, df=5 and 82, p=.005; Wilks' λ =.98, partial ή2 =.19). The mean scores and results of MANOVA for the outcome measures are shown in Table 1 . At the two posttests, results indicated that there were statistically significant differences between the two groups in caregivers' burden and quality of life and patients' symptom severity as well as frequency and length of institutionalization. Post hoc comparisons indicated that in the dementia care program, the caregivers' burden and quality of life and length of institutionalization at the two posttests and patients' symptom severity (as measured by the Neuro-psychiatric Inventory) at the six-month follow-up showed significantly greater improvements than in the control group. Family service utilization in the intervention group was reduced significantly at the 12-month follow-up.

Discussion

The findings provide preliminary support for the effectiveness of the dementia care management program in improving the symptom severity of persons with dementia and the psychological distress and quality of life of their family caregivers over the 12 months after enrollment in the program. Consistent with the findings of a few trials, this study found that persons with dementia whose family caregivers participated in an educational and supportive group showed significant improvements in a few of their family members' pathological behaviors (for example, hallucinations and aggression), and the length of institutionalizations ( 1 , 16 ). Because dementia care has been an increasing burden to family members and health care services, it is noteworthy that the families who underwent this psychosocial intervention reported significant improvements in their caregiving burden and quality of life without any increase in their need for family support services.

These findings suggest that providing a culturally sensitive and multidisciplinary dementia care management program, such as the dementia care program in this trial, can improve family caregivers' psychosocial health and can reduce patients' rates of institutionalization. Further research is recommended to examine the net effect of the psychosocial intervention in improving caregivers' knowledge and skills and reducing their burden and patients' pathological behaviors (for example, hallucinations). However, the therapeutic components of the intervention, which might contribute to the positive effects on the participants, were not tested in this study. Routine care was chosen as the control intervention; as such, the Hawthorne effect cannot be excluded. Future process and outcome evaluation of this program with a larger and more diverse sample and a longer follow-up period can provide evidence applicable to Chinese or other Asian populations.

Conclusions

This study found the dementia care management program to be an effective community-based intervention for family members of Chinese persons with dementia, compared with routine dementia care. The intervention was limited to six months in two dementia day care centers. Further research on this intervention and comparison with other models of family intervention with larger samples of diverse sociocultural backgrounds are recommended.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grant 2005–06 from the Nethersole School of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The authors thank the dementia care centers and their staff for their assistance in the recruitment of participants and data collection.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al: Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups. Annals of Internal Medicine 145: 727–738, 2006Google Scholar

2. Brodaty H, Green A, Koschera A: Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51: 657–664, 2003Google Scholar

3. Schultz R, Martire LM, Klinger JN: Evidence-based caregiver interventions in geriatric psychiatry. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 28:1007–1038, 2005Google Scholar

4. Schulz R, Martire LM: Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health needs, and support strategies. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 12:240–249, 2004Google Scholar

5. Fung WY, Chien WT: The effectiveness of a mutual support group for family caregivers of a relative with dementia. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 14:134–144, 2002Google Scholar

6. Cohen J: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin 112:155–159, 1992Google Scholar

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

8. Cummings JL, Frank JC, Cherry D, et al: Guidelines for managing Alzheimer's disease: part I. assessment. American Family Physician 65:2263–2272, 2002Google Scholar

9. Chou KR, Jiann-Chyun L, Chu H: The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Caregiver Burden Inventory. Nursing Research 51:324–331, 2002Google Scholar

10. Leung KF, Tay M, Cheng SSW, et al: The Hong Kong Chinese Version World Health Organization Quality of Life Measure—Abbreviated Version, WHOQOL-BREF (HK). Hong Kong SAR, P. R. China, Hospital Authority Hong Kong, Hong Kong Project Team on Development of the Chinese Version WHOQOL, 1997Google Scholar

11. Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, et al: A brief measure of social support: practical and theoretical implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationship 4:497–510, 1987Google Scholar

12. Cummings JL: Neuro-psychiatric Inventory update. Los Angeles, Reed Neurological Research Center, 1998Google Scholar

13. Chiu HFK, Lee HC, Chung WS, et al: Reliability and validity of the Cantonese version of Mini-Mental State Examination—a preliminary study. Journal of Hong Kong College of Psychiatry 4:25–28, 1994Google Scholar

14. Heller T, Factor A: Permanency planning for adults with mental retardation living with family caregivers. American Journal of Mental Retardation 96:163–176, 1991Google Scholar

15. Chien WT, Chan SWC, Thompson DR: Effects of a mutual support group for families of Chinese people with schizophrenia: 18-month follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 189:41–49, 2006Google Scholar

16. Eng C, Pedulla J, Eleazer GP, et al: Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE): an innovative model of integrated geriatric care and financing. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45:223–232, 1997Google Scholar