Use of Professional and Informal Support by African Americans and Caribbean Blacks With Mental Disorders

Research on mental health service utilization has consistently found that most adults with a mental disorder do not receive treatment. According to recent national surveys, less than half of adults with a mental disorder used services in the 12 months before being interviewed ( 1 , 2 ). Persons belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups, in particular, underutilize mental health services. African Americans, for example, have been found to be less likely than whites to use outpatient mental health services ( 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). Only 32% of black Americans with a mental disorder have been found to use professional services ( 2 ), and only 22% of Caribbean blacks and 48% of African Americans with severe symptoms of major depression receive treatment ( 8 ). These findings suggest that the service needs of a significant proportion of black Americans with mental disorders are not being met.

Although it is possible that those who do not use professional services instead receive help from informal support networks, evidence for this hypothesis is mixed. One study of older African-American residents of public housing found that they were more likely to use professional services than informal help ( 9 ). Other studies have found a tendency of adults with a mental disorder to use informal support as a complement to rather than a substitute for professional services ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). These studies, however, had samples with limited generalizability or focused on the receipt of informal care as a predictor of professional service use.

In contrast, research based on data from the National Survey of Black Americans examined the use of professional services and informal support simultaneously. This survey found that when faced with a personal problem, roughly equal proportions of African Americans used informal support or a combination of professional services and informal support, whereas much smaller proportions relied on professional services only or did not receive help at all ( 14 ). Informal support was, therefore, an important source of assistance both in conjunction with and in place of professional services.

This study examined the use of four help-seeking options—the use of professional services only, informal support only, a combination of the two, or neither—among African-American and Caribbean black adults who met diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder. This study allowed us to build on existing knowledge in several ways. First, we considered the characteristics of nonusers of both professional services and informal support to broaden our understanding of the help-seeking process among adults with a mental disorder. Second, we included individuals who met diagnostic criteria for a lifetime mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder to better understand how both mental disorders and substance use disorders are related to patterns of help seeking. Third, we included Caribbean black residents of the United States, a small but significant portion of the general black American population.

Methods

Sample

This study used data from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) ( 15 ). The NSAL is based on an integrated national household probability sample of 6,082 African Americans, non-Hispanic whites, and blacks of Caribbean descent age 18 or older. Data were collected between February 2001 and June 2003 by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research. After complete description of the study to the participants, informed consent was obtained. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

The analytic sample included 1,096 African Americans and 372 Caribbean blacks who met diagnostic criteria for a mood disorder (major depression, dysthymia, or bipolar disorder I or II), an anxiety disorder (panic, social phobia, agoraphobia without panic, generalized anxiety, or posttraumatic stress), or a substance use disorder (alcohol abuse or dependence or drug abuse or dependence). Mental disorders were assessed with the DSM-IV World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview, a fully structured diagnostic interview ( 16 ).

Measures

The dependent variable consisted of four mutually exclusive categories for describing patterns of help that respondents could seek for their mental disorder—professional services only, informal support only, both professional services and informal support, or no help. For each disorder, respondents were asked two questions related to help seeking. For example, for depression, respondents were asked, "Did you ever in your life talk to a medical doctor or other professional about your [sadness, discouragement, or lack of interest]?" and "Did you ever in your life receive any help from family, friends, or other acquaintances for your [sadness, discouragement, or lack of interest]?" These questions were asked for each disorder, with substitution of the appropriate descriptors.

Demographic characteristics included ethnicity (African American or Caribbean black), age in years, gender, and marital status (currently married, previously married, or never married). Socioeconomic status was measured by employment status (working or not working), education (high school or less, some college, or a college degree or higher), and a poverty index (ratio of family income to the U.S. Census poverty threshold for 2001). There was also a dichotomous measure of whether or not the respondent had health insurance.

A three-category variable indicated whether the respondent had a mental disorder only, a substance use disorder only, or co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. A four-level rating of overall mental illness severity was determined for the 12 months before the interview (severe or serious, moderate, mild, or none) ( 17 ). Because the sample for this study was limited to persons with a lifetime disorder, the fourth category corresponds to persons who met criteria for a lifetime disorder but had not experienced an episode within the past 12 months.

Finally, three variables described the family network of respondents: a continuous measure of the size of the helper network, frequency of contact with family members (from 0, never, to 6, nearly every day), and subjective family closeness (from 0, not close at all, to 3, very close).

Analysis

Cross-tabulations are presented to illustrate the independent effect of each predictor on the use of professional services and informal support. The Rao-Scott chi square for categorical variables and an F means test for continuous variables are presented. Multinomial logistic regression analysis tested the use of professional services and informal support, with controls for sociodemographic characteristics, disorder-related variables, and family network variables. The reference category was the use of both professional services and informal support. All statistical analyses were performed with the survey commands in Stata 9.2, which accounted for the complex multistage clustered design of the NSAL sample, unequal probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and poststratification to calculate weighted, nationally representative population estimates and standard errors. All percentages reported are weighted.

Results

Forty-one percent of respondents (N=598) used both professional services and informal support, 14% (N=197) relied on professional services only, and 23% (N=339) used informal support only. Twenty-two percent (N=334) did not seek help. Table 1 presents the bivariate analysis of the independent variables and the source of help. Respondents who relied exclusively on informal support were on average younger than those who utilized other categories of help seeking. More men than women did not seek help, and almost half of women used both professional services and informal support.

|

On average the ratio of income to the poverty threshold was higher for respondents who relied on informal support only or sought both professional services and informal support than for respondents who used professional services only or received no help. A higher proportion of respondents who were working used only informal support or sought no help at all. Compared with respondents currently or never married, a smaller proportion of respondents who were previously married did not seek any help or relied on informal support only.

In terms of disorder-related variables, a greater proportion of respondents with a substance use disorder did not seek help compared with those with a mental disorder only and those with co-occurring disorders. A greater proportion of respondents with a mental disorder relied exclusively on informal support compared with those with a substance use disorder or co-occurring disorders. Almost three-quarters of respondents with a severe 12-month disorder used both professional services and informal support, which is substantially more than for those with less severe disorders.

Finally, a greater proportion of respondents who had smaller helper networks used professional services only. Those with more frequent contact with family used both professional services and informal support or informal support alone, whereas respondents who had lower levels of subjective family closeness used professional services only.

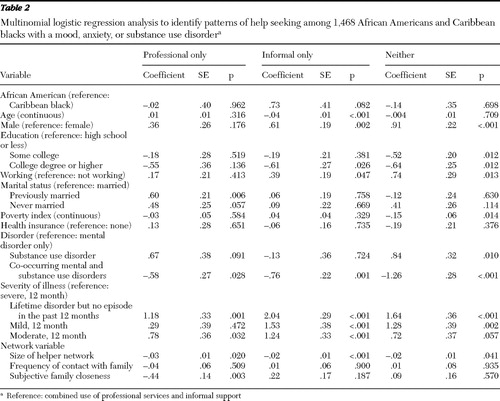

In multinomial logistic regression analyses, all variables except ethnicity and having insurance coverage were significantly related to patterns of help seeking ( Table 2 ). Younger adults had a higher likelihood of using informal support than using both professional services and informal support. Men were more likely than women to use informal support only or to not seek help at all compared with using both professional services and informal support.

|

Respondents with a college degree or higher were less likely than those with a high school degree or less to use informal support alone compared with using both professional services and informal support. Respondents with some college or a college degree or higher were more likely to seek help. Respondents who were working were more likely than those who were not working to rely exclusively on informal support or to not seek help at all. Those who were previously married were more likely than those who were currently married to use only professional services compared with using both professional services and informal support. The higher the ratio of household income to the poverty threshold the more likely that the respondent received help; that is, those living closer to poverty were less likely to receive any help.

The type of disorder was related to the pattern of professional and informal support. Respondents with co-occurring disorders were more likely than those with a mental disorder alone to use both professional services and informal support. Similarly, respondents with a severe disorder over the past 12 months were more likely than those with less severe disorders to use both professional services and informal support. Those with a substance use disorder were more likely than those with a mental disorder to not use services.

Finally, in terms of the family network, the larger the helper network the less likely that the respondents relied on professional services only, informal support only, or no help. The closer the respondents felt to their family the less likely they were to use only professional services.

Discussion

The findings of this study add to our understanding of help seeking among black Americans with a mental disorder. Less than half of black Americans in this study used both professional services and informal support. The remainder relied exclusively on informal support (23%) or professional services alone (14%), or they sought no help (22%). Although relying on informal support alone can limit the assistance available, this kind of support may be sufficient for more mild and less persistent disorders. Relying on professional services alone, however, may limit the day-to-day help that individuals receive. The significant proportion of black Americans with a mental disorder who were relying on informal support alone, professional services alone, or no help suggests potential unmet need in this group.

Informal support may play a protective role against the development of disorders. Previous research has found that, despite greater social disadvantages and stressors, members of racial and ethnic minority groups have consistently experienced a lower lifetime prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders than non-Hispanic whites ( 8 , 18 , 19 ). Indeed, the fact that over 60% of black Americans in this sample relied on informal support either alone or in conjunction with professional services suggests the presence of a strong social fabric that may buffer individuals from mental health problems as well as provide help in a time of need. Additional research on the protective role of informal supports as well as the type and adequacy of help provided by both informal and professional sources would help clarify the extent to which underutilization of services equates to unmet need. In addition, the protective role of support from extended family, religious participation, and friends and other nonkin acquaintances (such as church members) should be investigated given the important role of these resources in the lives of black Americans ( 20 , 21 ).

Respondents with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders and those with a more severe 12-month disorder were more likely overall to seek help and to use both professional services and informal supports than those with a mental disorder only or those with a less severe disorder. However, those with solely a substance use disorder were less likely to seek any help. These findings are consistent with previous research on professional service use ( 22 , 23 , 24 ) and indicate that greater illness severity increases the overall intensity of help seeking and the variety of sources from which help is received. In addition, the help-seeking process appears to be different for persons with substance use disorders versus other mental disorders. Other studies have also found that those with a substance use disorder are less likely to use services than those with a mental disorder ( 1 ) and that many individuals with co-occurring disorders receive treatment for substance use disorders only after entering mental health services ( 22 ). One reason for this finding may be that those with a substance use disorder are less likely to perceive a need for help ( 25 ). This study expands on previous research by including the use of informal support.

Respondents with larger helper networks were more likely to use both professional services and informal support. This finding is consistent with previous research and indicates that family members provide informal support and help facilitate access to professional services ( 12 , 26 , 27 ).

Previous research on service use has found that men are less likely than women to use professional services for a mental disorder ( 1 , 28 ) and are less likely in general to rely on informal support ( 29 , 30 , 31 ). This study suggests a more nuanced relationship. Black women were not only more likely than black men to seek help but also were more likely to seek help from a wider range of sources. These results are consistent with findings from the National Survey of Black Americans ( 14 ). In addition, when men sought help, they were more likely to rely exclusively on informal helpers. For men, informal support networks may be more likely to act as a substitute for or a barrier to professional service use. If true, this has implications for the quality of help that men receive, in that informal support networks are less equipped than professional service providers to deal with serious mental illness. This relationship between gender and the use of informal support is significant for African Americans but not for Caribbean blacks (analyses not shown), suggesting ethnic differences in gender and help seeking that should be investigated further.

Divorced, separated, or widowed respondents were more likely to use professional services only, whereas respondents who were currently married were more likely to use both professional services and informal support. One possible explanation for this finding is that spouses may facilitate access to professional services in addition to providing support themselves. Conversely, individuals who were separated or divorced as a consequence of mental illness were by necessity more likely to rely exclusively on professional services.

This study also found that the likelihood of using informal support alone declined with age. In particular, respondents of ages 18 to 29 were more likely to rely on informal support alone, whereas all other age groups were more likely to use a combination of professional services and informal support. Studies that have considered the use of only professional services have found that persons age 18 to 29 are more likely to receive treatment than older adults ( 1 , 32 ). In addition, Horwitz and Uttaro ( 11 ) found that younger adults were more likely than adults in other age groups to receive help from both family and professional services. These studies, however, did not examine differences within racial and ethnic groups. One reason for these contrasting findings may be that younger black Americans, more than other black Americans, face more barriers to accessing professional services. Alternatively, disorders among the younger age group may be less severe than for other age groups and may be successfully managed by informal support alone.

Several measures of socioeconomic status were related to help seeking. Respondents with more education were more likely to seek help and to receive help from both professional services and informal support. Higher levels of education may be associated with greater acceptance of seeking help for a mental disorder by the individual as well as by network members. In addition, education may be associated with a host of other barriers, stresses, and constraints faced by individuals of lower socioeconomic status that influence both the availability of and access to mental health services ( 33 ). Persons who were working were more likely than those not working to use no services or to rely exclusively on informal support. Respondents who were working may have had a less serious disorder and been able to continue working with the help of informal support. In fact, almost half of those currently working had a lifetime disorder only, whereas a greater proportion of those not working experienced a moderate or severe disorder in the past 12 months. Finally, in terms of income, the lower the household income the less likely respondents were to seek any help. This finding is consistent with previous research that has found that lower income is associated with less service use ( 1 , 32 , 34 ) as well as less use of informal support ( 29 , 35 ).

It should be noted that the use of measures of lifetime diagnosis and help seeking limited our ability to understand help seeking as a process. In particular, it was not possible to determine whether those who used both professional services and informal support used them simultaneously or serially. Similarly, for those who used informal support only or who did not seek any help, it was impossible to determine the extent to which their mental health needs were being met. Indeed, help seeking for a mental illness is acknowledged to be a complicated and dynamic process during which individuals move in and out of professional services, change the intensity of services used over time as their needs fluctuate, and experience shifts in their informal networks ( 27 ). Despite these limitations, this study makes an important contribution to our understanding of help seeking for a mental disorder among black Americans.

Conclusions

In this study, those who used only professional services tended to be separated, divorced, or widowed; to have fewer family members available to help; and to be less subjectively close to their family. These findings suggest that these individuals were isolated from their informal networks, although the reasons for that disconnection cannot be determined. These individuals could potentially benefit from interventions targeted toward enhancing relationships with existing informal helpers or creating new informal support connections. In addition, informal supports may buffer black Americans from developing a disorder in the first place. The role of informal support as a protective factor deserves further study.

There is an increasing emphasis on helping adults with serious mental illness to live in the community. The initiative outlined in the report of the President's New Freedom Commission goes beyond simply maintaining the mental health of individuals to improving their overall functioning and quality of life. Both professional services and informal support networks are crucial elements to make this effort successful. Adults with serious mental illness need help in many domains, including but not limited to mental health services. This assistance needs to be long term and flexible because of the often chronic and persistent nature of mental illness. Having access to multiple sources of support that can meet a variety of needs is crucial ( 36 , 37 ).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for this study came from grant U01-MH57716 from the National Institute of Mental Health, with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research at the National Institutes of Health; from the University of Michigan; from grants R01-AG18782 and P30-AG15281 by the National Institute on Aging; and from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

2. Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, et al: Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:485–494, 2007Google Scholar

3. Alvidrez J: Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal 35:515–530, 1999Google Scholar

4. Barrio C, Yamada AM, Hough RL, et al: Ethnic disparities in use of public mental health case management services among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 54:1264–1270, 2003Google Scholar

5. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ: Ethnicity and the use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public Health 84:222–226, 1994Google Scholar

6. Snowden LR: Barriers to effective mental health services for African Americans. Mental Health Services Research 3:181–188, 2001Google Scholar

7. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

8. Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors HW, et al: Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder among African Americans, Caribbean blacks and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). Archives of General Psychiatry 64:305–315, 2007Google Scholar

9. Black BS, Rabins PV, German P, et al: Use of formal and informal sources of mental health care among older African-American public-housing residents. Psychological Medicine 28:519–530, 1998Google Scholar

10. Snowden LR: Racial differences in informal help seeking for mental health problems. Journal of Community Psychology 26:429–438, 1998Google Scholar

11. Horwitz AV, Uttaro T: Age and mental health services. Community Mental Health Journal 34:275–287, 1998Google Scholar

12. Lam JA, Rosenheck R: Social support and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 45:13–28, 1999Google Scholar

13. Pescosolido BA, Wright ER, Alegría M, et al: Social networks and patterns of use among the poor with mental health problems in Puerto Rico. Medical Care 36: 1057–1072, 1998Google Scholar

14. Neighbors HW, Jackson JS: The use of informal and formal help: four patterns of illness behavior in the black community. American Journal of Community Psychology 12:629–644, 1984Google Scholar

15. Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, et al: The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:196–207, 2004Google Scholar

16. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J: The prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581–2590, 2004Google Scholar

17. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:617–627, 2005Google Scholar

18. Adams RE, Boscarino JA: Differences in mental health outcomes among whites, African Americans, and Hispanics. Psychiatry 68:250–265, 2005Google Scholar

19. Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, et al: Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychological Medicine 36: 57–68, 2006Google Scholar

20. Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Chatters LM: Supportive relationships with church members among African Americans. Family Relations 54:501–511, 2005Google Scholar

21. Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, et al: Patterns of informal support from family and church members among African Americans. Journal of Black Studies 33:66–85, 2002Google Scholar

22. Harris KM, Edlund MJ: Use of mental health care and substance abuse treatment among adults with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services 56:954–959, 2005Google Scholar

23. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17–31, 1996Google Scholar

24. Wang PSDH, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al: Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:603–613, 2005Google Scholar

25. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77–84, 2002Google Scholar

26. Kouzis AC, Ford DE, Eaton WW: Social relationships and psychiatric help-seeking. Research in Community and Mental Health 11:65–84, 2000Google Scholar

27. Pescosolido BA, Gardner CB, Lubell KM: How people get into mental health services: stories of choice, coercion and "muddling through" from "first-timers." Social Science and Medicine 46:275–286, 1998Google Scholar

28. Narrow WE, Regier DA, Norquist G, et al: Mental health service use by Americans with severe mental illnesses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:147–155, 2000Google Scholar

29. Thoits PA: Stress, coping, and social support processes: where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35:53–79, 1995Google Scholar

30. Antonucci TC, Birrin JE, Schaie KW, et al: Social relations: an examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control, in Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, vol 5. Edited by Birren JE, Schaie KW. San Diego, Academic Press, 2001Google Scholar

31. Keith PM, Kim S, Schafer RB: Informal ties of the unmarried in middle and later life: who has them and who does not? Sociological Spectrum 20:221–238, 2000Google Scholar

32. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, et al: Mental health service utilization by African Americans and Whites: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-Up. Medical Care 37:1034–1045, 1999Google Scholar

33. Williams DR: Socioeconomic differentials in health: a review and redirection. Social Psychology Quarterly 53:81–99, 1990Google Scholar

34. Klap R, Unroe KT, Unützer J: Caring for mental illness in the United States: focus on older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:517–524, 2003Google Scholar

35. Turner RJ, Marino F: Social support and social structure: a descriptive epidemiology. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35: 193–212, 1994Google Scholar

36. Biegel DE, Tracy EM, Corvo KN: Strengthening social networks: intervention strategies for mental health case managers. Health and Social Work 19:206–216, 1994Google Scholar

37. Pinto RM: Using social network interventions to improve mentally ill clients' well-being. Clinical Social Work Journal 34:83–100, 2006Google Scholar