Changing Trends in Pediatric Antipsychotic Use in Florida's Medicaid Program

After stable trends in the use of antipsychotic medications in the early 1990s ( 1 , 2 ), the past decade has shown substantial increases in the use of antipsychotic medications among youths in the United States and other parts of the developed world ( 3 , 4 ). From the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, increases ranging from 53% to 204% have been reported for Medicaid and commercially insured populations in the United States ( 5 , 6 ). During the same time interval, four- to fivefold increases in office visits resulting in antipsychotic prescriptions have occurred ( 3 ). Clearly driving these trends was the introduction of second-generation antipsychotic medications in the mid- to late 1990s ( 7 , 8 , 9 ). Risperidone initially led the way, closely followed by more recently released agents, including olanzapine and quetiapine ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ).

Although antipsychotic use increased for all age groups of children during the late 1990s and early 2000s ( 5 , 10 ), age-specific rates of increase varied, with the highest rates sometimes found among teenagers and sometimes among children ages five to nine years ( 10 , 14 ). Data on antipsychotic use in different studies can, however, be difficult to compare because of discrepant definitions of use and different study designs.

The trends of increasing antipsychotic use have caused concern in the general public as well as among professionals ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ). The concerns are related to the lack of approved Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications for most pediatric antipsychotic use and to the paucity of data regarding short- and long-term side effects ( 21 , 22 , 23 ). Of particular concern are the metabolic side effects of second-generation antipsychotic medications and their potential impact on brain development and the long-term health of children ( 24 , 25 , 26 ). The response to these concerns is limited by at least two considerations. First, our knowledge of prescribing trends is dated, precluding an understanding of the impact of more recently released antipsychotic agents, of emerging data on side effects, and of a variety of regulatory actions. Second, the trend data reported in the literature are generally organized by year, preventing fine-grained views of the response of physicians to time-specific changes in the prescribing environment. In response to these constraints, we present data on monthly antipsychotic use for Florida's child and adolescent Medicaid population from July 2002 to December 2005. We describe age-specific antipsychotic use rates and chart the changing patterns of use as new second-generation antipsychotic medications are assimilated into practice.

Methods

This study used Medicaid fee-for-service claims data for the period of July 2002 to December 2005. During this period the total number of youths age 18 and younger enrolled in Medicaid in Florida remained relatively constant at approximately 1.2 million enrollees. The percentage of youths in the fee-for-service program decreased by 6% (from 59% to 53% of total enrollees), whereas the percentage enrolled in health maintenance organizations increased by a like percentage. During this transition in enrollment there was also a tendency for youths with serious emotional disturbances to remain in the fee-for-service program ( 27 ).

National Drug Codes for antipsychotic medications in use in December 2006 were used to identify first- and second-generation antipsychotics ( 28 ).

In order to control for variations in enrollment, rates of antipsychotic use are expressed as the number of monthly users per 1,000 enrollees. A youth would be considered to be a "user" in any month if he or she had a claim paid on his or her behalf during that month. In the months in which more than one antipsychotic claim was paid for an individual, the youth would be counted as a user of both medications. Youths were classified into three age categories (zero to five, six to 12, and 13 to 18 years) to approximate preschool, elementary and middle school, and high school populations. An age in years was assigned to each child receiving an antipsychotic on the basis of the age entered on the pharmacy claim. Data for age were gathered at the beginning of each month, so that youths who were receiving an antipsychotic and those who were not receiving an antipsychotic could be placed in the appropriate age group.

Trends in antipsychotic use were analyzed by using piecewise regression with time in months as the independent variable and monthly users per 1,000 enrollees as the dependent variable. Piecewise regression is a method of modeling discontinuous relationships where two lines are joined at a breakpoint such that the intercept and slope before the breakpoint are different from the intercept and slope after the breakpoint. The estimates produced by a piecewise regression model can be used to test the hypothesis that the slopes in the period before May 2004 (July 2002 to April 2004, hereafter called period 1) and the period after April 2004 (May 2004 to December 2005, hereafter called period 2) were the same and to quantify the change that results from moving from one side of the breakpoint to the other ( 29 , 30 ). These two periods were chosen because a preliminary examination of the trends indicated that the relationship between time and utilization might be different for the period before May 2004 and the period after April 2004. Therefore, the models calculate and test the significance of the changes in trends that result from being in period 1 to being in period 2.

Results

The monthly total number of youths age 18 years and younger who were receiving an antipsychotic in Florida's Medicaid program increased from 5,797 in July 2002 to 8,425 in December 2005. Because the number of children receiving first-generation antipsychotics never exceeded 200 per month, this group was excluded from the trend analyses.

Antipsychotic use has also been found to vary by race and gender ( 11 , 31 , 32 ) Therefore, the distributions of both variables for the fee-for-service enrollees for each of the years of the study were compared for differences that might explain any changes in trends in antipsychotic use. No significant differences were observed, and in fact the distributions of both variables are virtually unchanged across the years. These distributions for the most recent full-year period in the analyses (fiscal year 2005) are presented in Table 1 with the categories available in the Medicaid claims data.

|

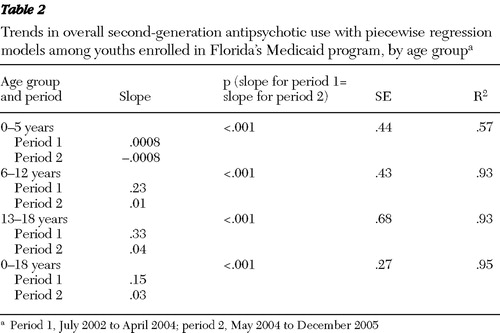

The trends for monthly users of second-generation antipsychotics per 1,000 enrollees among youths age 18 years and younger and for the three age subgroups are presented in Figure 1 for the entire 42-month study period. An analysis of the trends is presented in Table 2 .

|

We can see in Figure 1 that antipsychotic use for youths aged 18 years and younger was 8.3 per 1,000 enrollees in July 2002. By April 2004 it had increased to 11.3, and by December 2005 it was 11.6. The 13- to 18-year age group showed the highest use of second-generation antipsychotic medications during all 42 months of the study, followed by the six- to 12-year and the zero- to five-year age groups.

In Table 2 we see that for youths age 18 years and younger, there was a positive linear relationship in period 1 between time and monthly users per 1,000 enrollees. The trend changed after April 2004. It was essentially flat in period 2. The slopes describing the trends in antipsychotic usage in period 1 and period 2 were found to be significantly different. In the piecewise regression model, which incorporated these different slopes, time explained 95% of the variance among monthly users per 1,000 enrollees over the entire 42-month period.

The trends in antipsychotic use were different among the different age groups. As the age of youths increased, so did the rates of increase in monthly use per 1,000 enrollees in period 1. For preschool-age children, there was a small positive trend in period 1. In contrast, the trend was negative in period 2. The difference in linear trends between period 1 and period 2 was found to be significant. In the piecewise regression model, time explains 57% of the variance in monthly users per 1,000 enrollees. For the six- to 12-year and the 13- to 18-year age groups, there were positive linear trends in period 1, with use increasing more rapidly for the 13- to 18-year age group. In contrast, the trends were close to zero in period 2, indicating no growth in use during this period. The differences in the trends between period 1 and period 2 were found to be significant for both the six- to 12-year and the 13- to 18-year age groups. In the piecewise regression models, time explains 93% of the variance in monthly users per 1,000 enrollees for the two age groups.

Changes in the patterns of second-generation antipsychotic use were also observed for youths throughout the study period. These changes are summarized in Table 3 for youths ages six to 12 years and for those ages 13 to 18 years.

|

The most notable trend for both age groups was the rapid increase in the use of aripiprazole beginning in late 2002 when it came on the market ( 33 ). The trends were positive for both age groups for the two time periods. Although the differences in slopes between these two time periods were significant (p<.05), use increased steadily for both groups during both periods. This was the case despite the fact that the trend in period 2 was flat in second-generation antipsychotic use for youths age 18 years and younger. In the piecewise regression models, time explains about 98% of the variance in aripiprazole monthly users per 1,000 enrollees for both of the age groups.

In the case of risperidone, the trends for both age groups were only slightly positive in period 1 and negative in period 2. The differences in slopes from period 1 to period 2 are significantly different for both age groups, indicating changes in linear trends beginning in the spring of 2004. The R 2 values for the piecewise regression models for both age groups are .67.

For quetiapine, for the six- to 12-year age group there was a slightly positive slope for the relationship between time and monthly users per 1,000 enrollees in period 1. The trend remained positive, although quite small, in period 2, and the difference in slopes from period 1 to period 2 was significant. For the 13- to 18-year age group, the positive trend in use was somewhat more pronounced in period 1. It was smaller in period 2, although not significantly different, indicating a somewhat consistent increase in use over the entire 42-month period.

There were slightly negative trends in the use of olanzapine in period 1 for both the six- to 12-year and the 13- to 18-year age groups. The negative trends became more pronounced in period 2, especially for the 13- to 18-year age group. The differences in slopes from period 1 to period 2 were significant for both age groups. Again, in the piecewise regression models, time explains 95% of the variance in monthly users per 1,000 enrollees over the 42-month period.

Ziprasidone use was stable and very low for all three age groups during the entire study period.

Figure 2 portrays the changing patterns of antipsychotic use for the 13- to 18-year age group, in which the trends were most pronounced.

Clearly for the 13- to 18-year age group there was significant growth in the use of aripiprazole and quetiapine over the 42-month period, accompanied by a large decline in olanzapine use and a more modest decline in the use of risperidone in period 2.

Discussion

The data from Florida's Medicaid program indicate that the rapid increases in antipsychotic use in pediatric populations—consistently observed by researchers studying the period from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s and observed in the first 21 months of this study—stopped for all age groups beginning in the April 2004 to June 2004 period. For the six- to 12-year and the 13- to 18-year age groups, time was an excellent determinant of rates of use. The changes in trends could be explained at least in part by discussion in the Florida legislature during the spring of 2004 about the rapidly increasing expenditures for antipsychotic medications. Highlighting the expenditure issue may have affected antipsychotic prescribing patterns. Also relevant to the trends in the latter part of period 2 was the implementation of a pharmacy utilization management program that monitored practice and provided feedback to individual physicians for observed patterns of unusual practice from December 2004 to June 2005 ( 34 , 35 ).

Given the timing of these changes, it is also likely that they are related to the accumulation of information about the metabolic side effects of some of the second-generation antipsychotic medications ( 36 , 37 ), and especially to label warnings required by the FDA in the fall of 2003 ( 38 ). Perhaps as relevant for pediatric prescribing was the black box warning required by the FDA in March 2004 for pediatric antidepressant prescriptions ( 39 ). One would expect that these actions would have made physicians more cautious from a clinical, medical, and legal perspective about prescribing psychotherapeutic medications to youths in general and about prescribing antipsychotic medications in particular. The change in trends in use and its specific timing seem to suggest that these factors did have an impact.

It is also possible that antipsychotic use in April 2004 reached a natural ceiling and that the flattening of the trends beginning at that time reflects this reality. However, this seems unlikely because in 2003, several other state Medicaid programs had annual rates of antipsychotic use for youths that were higher than that for youths in Florida in 2004 (annual rate of 14 users per 1,000 enrollees) ( 6 ).

The significant changes in the specific second-generation antipsychotic medications prescribed for children and adolescents that occurred in Florida during the study period are probably explained, in part, by the growing body of research on the differences between these medications with regard to metabolic syndrome ( 40 , 41 , 42 ). Concerns about the side effects of second-generation antipsychotic medications were already being expressed in the early 2000s ( 43 , 44 , 45 ). They culminated in the Consensus Statement of the American Diabetes and the American Psychiatric Associations in February of 2004, which concluded that olanzapine and clozapine were associated with the greatest risk of weight gain and highest occurrence of diabetes and dyslipidemia ( 44 ). Given these concerns, it is not surprising that olanzapine use among children and adolescents began trending downward in the summer of 2003 and declined significantly in period 2. By December 2005 olanzapine was the least prescribed of the second-generation antipsychotic medications with pediatric populations.

Changes in policy in Florida could have precipitated the change in the prescribing of olanzapine, making state-specific trends different from national trends. There were in fact two changes in policy that affected olanzapine use during period 2. The first involved limitations on dosing options, but not access to, olanzapine in the summer of 2004. The second involved the implementation of a preferred-drug list for psychotherapeutic medications in July 2005. With regard to the former, the significant decline in olanzapine use began four to five months before the policy took effect, and in fact, a gradual downward utilization trend began in 2003. The downward trend after April 2004 does not appear to have been precipitated by the policy change, but it may have been enhanced by it.

In the case of the preferred-drug list, olanzapine was the only second-generation antipsychotic that required prior authorization during the first two months of implementation. A suspension of the prior authorization requirement took effect in mid-September 2005. To determine whether the decline in the use of olanzapine during this 60-day period was responsible for the significant differences in slopes between period 1 and period 2, we recalculated the slopes by ending period 2 in June of 2005 (instead of December 2005), just before the preferred-drug list policy took effect. We did the same for the other second-generation antipsychotics to determine whether the temporary restriction on olanzapine might partially explain the increasing trend in aripiprazole and quetiapine use, at least in period 2. The effects on the slopes in period 2 were extremely small, and the probabilities that the period 1 and period 2 slopes are the same were unchanged.

The timing and direction of changes in utilization trends for risperidone and aripiprazole also appear to have been affected by the Consensus Statement ( 44 ). The use of risperidone, classified in the Consensus Statement as an "intermediate risk" ( 44 ), began a slow but steady and statistically significant decline for all three age groups after April 2004. Aripiprazole use began to increase in late 2002 when it was released to the market, perhaps reflecting a tendency on the part of prescribers to try new treatment technology ( 32 ). Growth in utilization occurred through April 2004 with the release of the Consensus Statement that classified it as one of the two drugs with the lowest risk of causing metabolic side effects, and growth continued through December 2005, well beyond the intensive postrelease marketing campaign. Explanations for the trends in quetiapine and ziprasidone utilization are less clear. Although by the Consensus Statement the former was grouped with risperidone as carrying an intermediate risk ( 44 ), its use with the 13- to 18-year age group increased throughout the study period. Ziprasidone use remained stable and low throughout the study period, despite its favorable side effect classification in the Consensus Statement.

In Florida the most rapid increase in use of antipsychotics occurred with teenagers. This comports with observations regarding new antipsychotic utilization in TennCare ( 14 ) but is inconsistent with other research indicating that growth was greatest for the five- to nine-year age groups ( 6 ). The few studies of antipsychotic use among preschool-age children consistently report increased use in this age group ( 10 , 14 ). However, in Florida, there was a small but steady decline in period 2.

Several cautions should be noted in interpreting the results from the study presented here. First, the study dealt exclusively with Florida Medicaid enrollees. The findings may or may not reflect actual trends in other state Medicaid programs or in more broadly based commercially insured populations. However, at least with regard to the overall trends in antipsychotic use, there are some data indicating that the flattening out of antipsychotic utilization trends may not be unique to Florida. In a large sample of commercially insured children age 19 years and younger whose pharmacy benefits were managed by Medco, the annual rate of antipsychotic prescription growth slowed from 22% in 2003 to 14% in 2004 to 3% in 2005 ( 17 ). Second, the comparison of trends before May 2004 and after April 2004 was made after an inspection of the data. Explanations are therefore post hoc and require replication. Third, it is possible that reductions in the use of antipsychotic medications were driven by increases in nonpharmacy services provided to children who were previously receiving only medications. Fourth, nothing in the study presented here provides insight concerning the appropriate antipsychotic usage rates for pediatric populations. The utilization rates after April 2004 may actually reflect a continuation of excessive antipsychotic use or a failure to appropriately treat more children with antipsychotic medications.

Conclusions

Further research is needed to determine whether the changing trends in antipsychotic use observed in Florida since April 2004 reflect a broader national and international reality. If they do, it may be that the medical community responded relatively quickly to the recommendations of professional and regulatory organizations with a more cautious approach to pediatric antipsychotic use. If these trends are unique to Florida, they might reflect the impact of a focus on the cost of second-generation antipsychotics and the pharmacy management program these concerns produced.

What remains unclear is the meaning and value of these changes in prescribing practices. Needed is a clearer understanding of the diagnoses of the youths receiving antipsychotic treatments and the specific target symptoms being addressed by these treatments. These data are not available in Medicaid pharmacy data but can be accessed in service claims in future studies. This will set the stage for effectiveness and efficacy studies and for the epidemiological work that will enable us to compare actual antipsychotic use to what should be expected in Medicaid or general populations.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the leadership of the Agency for Health Care Administration for their proactive stance in requesting a study of the use of antipsychotic medications among children and adolescents in Florida's Medicaid Program. The authors also thank the staff of the agency for their assistance in securing access to the Medicaid claims data needed for this research and to the staff of the Policy and Research Data Center at the Florida Mental Health Institute for their assistance in data preparation and analysis. The study was funded by the Agency for Health Care Administration of the State of Florida as a component of the Medicaid Drug Therapy Management Program.

Dr. Constantine has research contracts with Janssen. The other author reports no competing interests.

1. Olfson M, Marcus S, Weissman, et al: National trends in use of psychotropic medications by children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:514–521, 2002Google Scholar

2. Najjar F, Welch C, Grapentine WL, et al: Trends in psychotropic drug use in a child psychiatric hospital from 1991–1998. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 14:87–93, 2004Google Scholar

3. Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:679–685, 2006Google Scholar

4. Schirm E, Tobi H, Zito JM, et al: Psychotropic medication in children: a study from the Netherlands. Pediatrics 108:e25, 2001Google Scholar

5. Cooper WO, Arbogast PG, Ding H, et al: Trends in prescribing of antipsychotic medications for US children. Ambulatory Pediatrics 6:79–83, 2006Google Scholar

6. Patel NC, Crismon L, Hoagwood K: Trends in the use of typical and atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:548–556, 2005Google Scholar

7. Doey T, Handelman K, Seabrook JA, et al: Survey of atypical antipsychotic prescribing by Canadian child psychiatrists and developmental pediatricians for patients aged under 18 years. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 52:363–368, 2007Google Scholar

8. Malone RP, Sheikh R, Zito JM: Novel antipsychotic medications in the treatment of children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 50:171–174, 1999Google Scholar

9. Towbin KE: Gaining: Pediatric patients and use of atypical antipsychotics. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:2034–2036, 2006Google Scholar

10. Patel NC, Sanchez RJ, Johnsrud MT, et al: Trends in antipsychotic use in a Texas Medicaid population of children and adolescents: 1996 to 2000. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 12:221–229, 2002Google Scholar

11. Curtis LH, Masselink LE, Ostbye T, et al: Prevalence of atypical antipsychotic drug use among commercially insured youths in the United States. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 159:362–366, 2005Google Scholar

12. Kelly DL, Love RC, MacKowick M, et al: Atypical antipsychotic use in a state hospital inpatient adolescent population. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 14:75–85, 2004Google Scholar

13. Martin A, Leslie D: Trends in psychotropic medication costs for children and adolescents, 1997–2000. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 157:997–1004, 2003Google Scholar

14. Cooper WO, Hickson GB, Fuchs C, et al: New users of antipsychotic medications among children enrolled in TennCare. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 158:753–759, 2004Google Scholar

15. Rawal PH, Lyons JS, MacIntyre JC II, et al: Regional variation and clinical indicators of antipsychotic use in residential treatment: a four-state comparison. Journal of Behavior Health Services and Research 31: 178–188, 2004Google Scholar

16. Staller JA, Wade MJ, Baker M: Current prescribing patterns in outpatient child and adolescent psychiatric practice in central New York. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 15:57–61, 2005Google Scholar

17. Antipsychotic drug use among kids soars: report raises concerns that mind-altering pills are being over prescribed. Associated Press, May 3, 2006. Available at www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12616864Google Scholar

18. Agovino T: Antipsychotic drug use among kids soars. Associated Press, May 2, 2006. Available at www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/n/a/2006/05/02/financial/f165329D34.DTL&type=printableGoogle Scholar

19. Farley R: The "atypical" dilemma: skyrocketing numbers of kids are prescribed powerful antipsychotic drugs. Is it safe? Nobody knows. St Petersburg Times, July 29, 2007. Available at www.sptimes.com/2007/07/29/Worldandnation/Theatypicaldi lemm.shtmlGoogle Scholar

20. Elias M: New antipsychotic drugs carry risks for children. USA Today, May 2, 2006. Available at www.usatoday.com/news/ health/2006-05-01-atypical-drugsx.htmGoogle Scholar

21. Cheng-Shannon J, McGough JJ, Pataki C, et al: Second-generation antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 14:372–394, 2004Google Scholar

22. Findling RL, Steiner H, Weller EB: Use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66(suppl 7): 29–40, 2005Google Scholar

23. Kapetanovic S, Simpson G: Review of antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Expert Opinion Pharmacotherapy 7:723, 2006Google Scholar

24. Patel NC, Crismon ML, Hoagwood K, et al: Unanswered questions regarding atypical antipsychotic use in aggressive children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 15:270–284, 2005Google Scholar

25. Jensen PS, Buitelaar J, Pandina GJ, et al: Management of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with atypical antipsychotics: a systematic review of published clinical trials. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry 16:104–120, 2007Google Scholar

26. Laita P, Cifuentes A, Doll A, et al: Antipsychotic-related abnormal involuntary movements and metabolic and endocrine side effects in children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 17:487–502, 2007Google Scholar

27. Constantine R, Murin M, Robst J: The Administrative Data Component of the Florida Managed Care Evaluation: Year 11. Tampa, University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, 2007Google Scholar

28. National Drug Code Directory. Rockville, Md, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, 2007. Available at www.fda.gov/cder/ndc/database/default.htmGoogle Scholar

29. Introduction to Stata: How Can I Run a Piecewise Regression in Stata? University of California, Los Angeles, Academic Technology Services, Statistical Consulting Group. Available at www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/faq/piecewise.htmGoogle Scholar

30. Paulson DS: Handbook of Regression and Modeling: Applications for the Clinical and Pharmaceutical Industries. Boca Raton, Fla, Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2007Google Scholar

31. Becker M, Jang Y: Evaluation of Florida Medicaid Behavioral Pharmacy Medication Practice by Race/Ethnic Minorities Across the Lifespan. Tampa, Fla, University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, 2005Google Scholar

32. Gersing K, Burchett B, March J, et al: Predicting antipsychotic use in children. Pharmacology Bulletin 40930:116–124, 2007Google Scholar

33. Aripiprazole Released November 2002. Rockville, Md, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical. Available at www.fda.govGoogle Scholar

34. Constantine R, Richard S, Surles R, et al: Optimizing pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia: tools for the psychiatrist. Current Psychosis and Therapeutics Reports 4:6–11, 2006Google Scholar

35. Tandon R, Dewan N, Constantine R, et al: Best pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia: applying principles of evidence-based medicine. Current Psychosis and Therapeutic Reports 3:53–60, 2005Google Scholar

36. Sacks FM: Metabolic syndrome: epidemiology and consequences. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 18(65 suppl):3–12, 2004Google Scholar

37. Melkersson K, Dahl ML: Adverse metabolic effects associated with atypical antipsychotics: literature review and clinical implications. Drugs 64:701–723, 2004Google Scholar

38. Rosack J: FDA to require diabetes warning on antipsychotics. Psychiatric News 38:20, 2003Google Scholar

39. "Black box" warning for antidepressants. ScienceDaily, Dec 3, 2004. Available at www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2004/12/041203100252.htmGoogle Scholar

40. Newcomer JW: Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs 19(suppl 1):1–93, 2005Google Scholar

41. Newcomer JW: Abnormalities of glucose metabolism associated with atypical antipsychotics. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:36–46, 2004Google Scholar

42. Tandon R, Belmaker RH, Lopez-Ibor JJ Jr, et al: World Psychiatric Association Pharmacopsychiatry Section statement on comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 100:20–38, 2008Google Scholar

43. Findling R, McNamara N, Gragious B: Paediatric uses of atypical antipsychotics. Expert Opinion Pharmacotherapy 1:935–945, 2000Google Scholar

44. Consensus Development Conference on Antipsychotic Drugs and Obesity and Diabetes. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:267–272, 2004Google Scholar

45. Harrison-Woolrych M, Garcia-Quiroga J, Ashton J, et al: Safety and usage of atypical antipsychotic medicines in children: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Drug Safety 30:569–579, 2007Google Scholar