Improving Knowledge About Mental Illness Through Family-Led Education: The Journey of Hope

Families are a primary caregiving resource for adults with mental illness, yet they often lack the knowledge and skills needed to assist their relatives ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ). Studies show that families routinely request information on basic facts about mental illness and its treatment, behavior management skills, and the mental health system in order to better cope with their relatives' illness ( 6 , 7 , 8 ). Recognizing families' caregiving roles and knowledge needs, numerous treatment guidelines recommend that families receive psychosocial interventions that educate them about the causes and treatment of mental illness, coping strategies, and community resources ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ). Participation in one such intervention, family psychoeducation, has been found to increase families' knowledge and coping ability ( 13 , 14 , 15 ). Family psychoeducation interventions typically are professional-led programs lasting nine months or longer, adjunctive to the relative's treatment, and focus on improving clinical outcomes. These programs include information on the etiology of mental illness, standard treatments, and problem management. However, the long-term, clinic-based nature of these programs often makes them difficult to implement, thereby limiting their availability ( 16 , 17 , 18 ).

Family-led education programs, such as the eight-week Journey of Hope education course and National Alliance on Mental Illness's 12-week Family-to-Family Education Program, are community-based, treatment-independent interventions that seek to strengthen families' coping competencies. Taught by trained volunteer instructors who themselves have an adult relative with mental illness, family-led education program curricula cover brain biology, medications, the mental health system, problem-solving skills, and family support ( 19 , 20 ). The number and availability of family-led interventions have grown substantially in recent years, making them a potentially valuable resource.

Studies of family-led programs suggest that these interventions may increase participants' knowledge of the causes and treatment of mental illness and improve their ability to cope with illness-related problems ( 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ). In an early evaluation of the Journey of Hope, Pickett-Schenk and her colleagues ( 22 ) used mail surveys to assess outcomes reported by 424 participants. Respondents reported that, as a result of taking the Journey of Hope course, they increased both their knowledge of the causes and treatment of mental illness and the mental health system. Dixon and associates ( 20 ) employed a nonrandomized, wait-list design to examine outcomes among 95 participants of the Family-to-Family Education Program. Receipt of this program was significantly associated with improved knowledge about mental illness and the treatment system; these knowledge gains were maintained six months after program participation.

Although promising, these studies were not controlled trials; therefore, improvements in participants' knowledge cannot be attributed to participation in the family-led interventions. We take the next step in this research by presenting findings from a study of the Journey of Hope that used a randomized wait-list design to examine the effectiveness of this intervention in improving family coping outcomes. Two prior publications provide greater detail on the study design and Journey of Hope course ( 24 , 25 ). As described in these articles, participation in the Journey of Hope course improved family members' emotional well-being and views of their relationships with their ill relative ( 24 ), increased their caregiving satisfaction, and decreased their needs for information on problem management and relatives' social functioning ( 25 ). However, these studies did not explore whether participation in the Journey of Hope results in knowledge gains or meets families' need for information on a broad range of illness-related topics. Given that 73% of participants reported that no professionals had ever offered them education or support services before they enrolled in the study, we believe that further examination is warranted of whether the Journey of Hope course provided participants with the knowledge and skills they need to cope with their relative's illness.

Additionally, Psychiatric Services readers include individuals who may have limited access to these articles and who may be interested in addressing families' information needs, such as advocacy organization administrators, family members, and community-based treatment providers. Thus this article has two goals: to examine the effectiveness of the Journey of Hope education course in improving families' knowledge and decreasing their information needs and to share the empirical evidence for these outcomes with readers who may be likely to implement similar interventions or to refer families to them. We tested two hypotheses: first, compared with control group participants, Journey of Hope participants would report increased knowledge of the causes and treatment of mental illness and problem-solving skills and they would report fewer information needs and, second, these differences in knowledge and information need outcomes would be maintained over time.

Methods

Journey of Hope education course

The Journey of Hope is a manualized, family-led education program that provides families with the education, skills training, and emotional support that they need as primary caregivers for adults with mental illness. The course is taught by a team of two trained volunteer instructors who are family members of adults with mental illness. Family members are encouraged to take the Journey of Hope course together. However, so that families feel comfortable discussing their relative's illness, their ill relative is not allowed to attend.

Journey of Hope curriculum covers the biological causes and standard treatments of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder; problem-solving skills; coping strategies; normative reactions to mental illness; self-care; community treatment programs; and consumer recovery. Journey of Hope is taught in nonclinical, public settings. The course and all materials are free to participants. Classes meet once a week for two hours for eight consecutive weeks; class sizes range from ten to 15 participants.

Procedure

The study was conducted in three sites in southeastern Louisiana where Journey of Hope was taught on a regular basis. Participants were randomly assigned to either immediate enrollment in the Journey of Hope (intervention group) or a nine-month waiting list for the course (control group). Data were collected from December 2000 to June 2004. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals.

Families were recruited to participate in the study via newspaper articles and advertisements, television public service announcements, and flyers posted throughout the community. Interested individuals were screened by telephone by research staff to assess their eligibility criteria, which included being a family member of a person who had one of the five diagnoses discussed in the Journey of Hope education course, being 18 years old or older, and expressing a willingness to participate in the Journey of Hope course. Individuals uncertain of their relative's diagnoses underwent a second telephone screening by the project's co-principal investigator, a board-certified psychiatrist, who determined whether the relative's symptoms, as described by the family, met DSM-IV ( 26 ) criteria for mental illness. Research staff met with eligible individuals to further discuss study procedures and obtain informed consent. Of the 542 individuals who met eligibility criteria, 72 (13%) declined project participation and were referred to other family support services.

Randomization. Families were recruited, enrolled, and randomly assigned to study groups in six waves from December 2000 to August 2003. For each wave, at each site, consent documents were consecutively numbered according to the date they were signed, and a computer-generated list of random numbers was used to assign half of the participants to the intervention group and half to the control group. In keeping with the principles of the Journey of Hope program, participants from the same family group (that is, siblings or married couples) were assigned to the same study condition. We enrolled 470 participants in the study; eight participants withdrew before randomization. A total of 462 enrolled participants were randomly assigned to the two study conditions, with 231 assigned to the intervention group, and 231 assigned to the control group. Intervention group participants attended a mean±SD of 5.98±2.34 classes.

Interviews. In-person, structured interviews were conducted with intervention and control group participants at the same three time points: one month before the start of the course for intervention group participants (time 1, study baseline for the control group), at course termination (time 2, three months postbaseline for the control group), and six months postcourse termination (time 3, eight months postbaseline for the control group). Interviews assessed several outcomes, including participants' knowledge of the etiology and treatment of mental illness, knowledge of problem-solving skills, and information needs. Participants' demographic characteristics and their ill relatives' clinical characteristics also were collected. Participants received $25 for each completed interview. Nearly all (429 participants, or 93%) of both intervention and control group participants completed time 2 interviews, and 89% of both groups (N=411) completed time 3 interviews.

Measures

Knowledge. Given that no known instrument with established psychometric properties existed that measured information imparted in the Journey of Hope course, we developed the Family Knowledge Scale before intervention implementation. The scale consists of 40 multiple-choice items and assesses knowledge regarding topical areas covered in each of the eight classes and knowledge of problem-solving skills. In order to determine whether items combined into specific knowledge areas or subscales, principal components factor analysis of time 1 data was conducted. Based on item content, an eight-factor solution was selected and varimax rotation was used to obtain simple structure. Eigenvalues ranged from 1.34 to 3.43; together, the eight factors accounted for only 35% of the sample variance. These results suggest that scale items assess a general knowledge of mental illness and problem-solving skills. Knowledge scores were created by summing together correct responses to each of the 40 items on the scale; higher scores indicate greater overall knowledge of mental illness and problem-solving skills. The measure had adequate internal reliability with an overall Cronbach's alpha of .66.

Information needs. The Family Information Needs scale ( 6 ) measured participants' information needs. This scale asks participants to rate their interest in learning about 45 specific topics, such as medication and coping strategies, along a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, not interested, to 5, very interested. Principal components factor analyses using a varimax rotation derived six factors with eigenvalues ranging from 1.39 to 12.72 and accounting for 52% of the time 1 sample variance. The six information need subscales include coping with positive symptoms (five items), coping with negative symptoms (six items), problem management (five items), enhancing relative's social functioning (eight items), basic facts about mental illness (ten items), and community resources (11 items). Items in each subscale were summed together to create a composite score; higher scores indicate greater need for information about the subscale topic. Internal consistency for each subscale was strong, with Cronbach's alphas ranging from .75 to .91.

Study condition and control variables. Participants' group assignment was a dichotomous variable coded as 1 if participants were assigned to the Journey of Hope course and 0 if participants were assigned to the control group. Prior studies of family knowledge and information needs suggest that outcomes may be best for parents, Caucasians, older family members, those who do not reside with their ill relatives, and those whose relatives have a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia ( 6 , 20 , 22 , 25 , 27 ). Thus control variables used in the random regression analyses included participants' race (Caucasian versus non-Caucasian), age, relationship to the ill relative (parent versus other), the ill relative's co-residential status (lives with participant versus lives in other residential settings), and diagnosis (schizophrenia versus other). Service use also was included as a control variable in order to examine whether participants whose relatives received a greater number of services had more knowledge and fewer information needs than participants whose relatives received few or no services. During each interview participants were asked whether their ill relative currently used seven common services and supports, such as case management, or other services, such as supported education. Each item was a dichotomous variable coded as 1 if the relative use that service and 0 if he or she did not. Total service use in the analyses was calculated as the number of services relatives received at baseline.

Analysis

Student's t tests and chi square analyses were computed to determine whether significant differences existed between the intervention and control groups on participants' demographic characteristics and ill relatives' clinical characteristics. Next, SPSS-14 general linear models (GLMs) were computed to test the effects of study condition on the knowledge and information needs measures. Multivariate, longitudinal fixed-effects random regression analyses were then conducted via MIXOR to examine whether differences in outcomes between the two groups existed over time in the presence of the control variables. For each knowledge and information needs measure, a two-level random intercepts model was computed, with the control variables serving as fixed effects.

Results

As shown in Tables 1 and 2 , there were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in terms of the participants' demographic characteristics or the ill relatives' clinical characteristics. GLM results ( Table 3 ) indicate that each group had significant increases in knowledge scores and significant decreases in information needs at each interview time point. A significant interaction effect for study condition occurred for each outcome. Compared with participants in the control group, those in the intervention group reported significant increases in knowledge and significant decreases in information needs both at Journey of Hope course termination (time 2) and at six months after course termination (time 3).

|

|

|

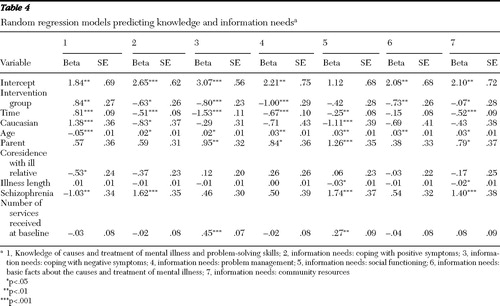

These GLM results were confirmed by the random regression analyses ( Table 4 ). With the exception of need for information on enhancing the relative's social functioning, there was a significant main effect for study condition for each outcome measure. Participants in the intervention group had greater knowledge scores and decreased information needs than did those in the control group. The effect of time also was significant, with participants in both groups reporting increased knowledge and decreased information needs from time 1 to time 3; the exception here is that there was no effect for time on need for information about basic facts about mental illness. There also were significant main effects for several control variables. Age was significant across all outcomes, with younger participants reporting greater knowledge and fewer information needs. Non-Caucasian participants and those whose relatives had diagnoses of schizophrenia reported lower knowledge and greater needs for information on coping with positive symptoms and information on social functioning. Parents had higher information need scores for coping with negative symptoms, problem management, basic facts about mental illness, and community resources.

|

Discussion

Family-led education interventions may be readily accessible resources. Yet, unlike family psychoeducation programs, we know little about whether these interventions improve family coping outcomes. Our findings suggest that, similar to psychoeducation programs ( 13 , 14 , 15 ), participation in family-led education interventions, such as the Journey of Hope, may provide family members with the knowledge and skills that they need to cope with their relative's mental illness. Compared with those in the control group, those in the Journey of Hope course had greater knowledge increases and information need decreases and maintained these gains six months after program participation.

Although our study did not test the effect of specific program components on families' knowledge and information needs, our results suggest that features of the Journey of Hope course may explain why participants in the intervention group achieved superior outcomes. Journey of Hope course materials and class discussions may increase participants' general understanding of mental illness and decrease their need for additional information on coping strategies and community resources. The unique use of family member instructors also may have helped participants both acquire and retain information. Studies suggest that interactions with peer instructors may improve participant outcomes because family members view their teachers as credible role models ( 28 , 29 ). Intervention participants may have been more receptive to course materials because they were delivered by a reliable source: another family member who is coping with a relative's mental illness and who understands families' information needs. Because families often report difficulty communicating with and receiving information from professionals ( 30 , 31 , 32 ), being in a course taught by other family members may have enabled participants in the intervention group to ask questions and participate in discussions that enhanced their learning.

The improved outcomes of participants in both groups also may be due to their use of other education and support services. To ensure that participants had access to needed services throughout their study participation, all participants received a list of local support services at enrollment. However, few intervention or control group participants used these services during their study participation, and differences between the groups regarding use of services other than the Journey of Hope were nonsignificant ( 24 , 25 ). It therefore is unlikely that knowledge and information gains were the result of receipt of outside educational resources.

Participants in the control group also had significant improvements in knowledge and information outcomes over time. Given that the majority of participants in the control group did not use other formal resources while waiting to receive Journey of Hope, these gains may be due to a process of continued maturation ( 3 ) in which family members' coping ability gradually improves over time. Control group participants' knowledge gains thus may be the result of their hands-on experience dealing with problems related to their relative's illness. The significant differences in outcomes between the groups, however, suggest that participation in the Journey of Hope may have sped up this process for participants in the intervention group, enabling them to more quickly acquire additional information needed to cope with their relative's illness.

Although large improvements in outcomes did not emerge among intervention group participants, it is important to remember that the majority of participants had never been offered any education services and had, on average, spent over a decade dealing with their relative's illness with little or no information on the etiology of mental illness or coping strategies. It is possible that participants could not, in this initial receipt of education, learn all of the information delivered in the Journey of Hope course. These small changes in outcomes may reflect that participants retained only information that best met their coping needs.

We did not assess the potential effect of specific program components on the intervention group participants' improved outcomes, such as whether skills training exercises or certain didactic materials are associated with knowledge gains. Additionally, it is possible that these participants' improved outcomes are the result of being in a supportive environment with other families, rather than as a result of the Journey of Hope curriculum itself. This may have led to informal information exchanges between participants about local treatment programs or ways to solve specific problems. Potential contamination effects also were not assessed: participants in the intervention group may have increased their knowledge and decreased their information needs through other educational activities, such as reading books or watching movies about mental illness.

Results also may be related to participants' unassessed motivation for enrolling in the study. Information on topics discussed in the Journey of Hope course was shared with family members during recruitment. Individuals may have decided to participate in the project in order to receive specific information related to their relative's illness. For example, significant decreases in information on coping with positive symptoms may not be due solely to Journey of Hope participation but to participants' prestudy interest in learning about this specific topic.

There also are limitations related to study design. Our knowledge measure assesses only information imparted in the Journey of Hope course. We do not know whether intervention group participants' knowledge of other topics, such as borderline personality disorder, also increased. Although use of an inactive control group may have been a better alternative than a wait-list design, we felt that it was unethical to deprive control group participants who had enrolled in the study seeking family-led education for help with caregiving concerns of the opportunity to receive Journey of Hope. Similarly, although a 12- or 24-month follow-up period would have allowed us to examine long-term outcome changes, we believed it was wrong to make control participants wait a year or more to receive the Journey of Hope course. Thus, to minimize these risks, we chose a wait-list design guaranteeing receipt of the Journey of Hope course and replicated follow-up periods used in prior family education studies ( 3 , 33 ).

Conclusions

Our results contribute to the evidence base establishing family-led programs as effective educational resources for families of adults with mental illness. Participation in the Journey of Hope increases families' knowledge and provides them with information on mental illness that they may seldom seek or receive from professionals. Studies examining the effect of specific program components are needed to help us better understand the mechanisms that result in improved knowledge outcomes for participants in the family-led intervention.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant R01-MH-60721 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Contents do not reflect the official position of this agency and no endorsement should be inferred. The authors thank Steve Augillard, M.S.W., Pam Cameron, M.S.W., Jeanne Dunne, B.S.N., Rhonda Norwood, M.S.W., Ian Villagracia, B.A., Jane Burke-Miller, M.A., and the Journey of Hope study instructors for their invaluable assistance with this project.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Doornbos MM: The 24-7-52 job: family caregiving for young adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Journal of Family Nursing 7:328–344, 2001Google Scholar

2. Marsh DT, Johnson DL: The family experience of mental illness: implications for intervention. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 28:229–237, 1997Google Scholar

3. Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, et al: Effectiveness of two models of brief family education: retention of gains by family members of adults with serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:177–186, 1997Google Scholar

4. Pollio DE, North CS, Reid DL, et al: Living with severe mental illness—what families and friends must know: evaluation of a one-day psychoeducation workshop. Social Work 51:31–38, 2006Google Scholar

5. Heru AM: Family functioning, burden, and reward in the caregiving for chronic mental illness. Family, Systems and Health 18:91–103, 2000Google Scholar

6. Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Wade JH, et al: An assessment of the educational needs of chronic psychiatric patients and their relatives. British Journal of Psychiatry 160:674–680, 1992Google Scholar

7. Gasque-Carter OK, Curlee MB: The educational needs of families of mentally ill adults: the South Carolina experience. Psychiatric Services 50:520–524, 1999Google Scholar

8. Ascher-Svanum H, Lafuze JE, Barrickman PJ, et al: Educational needs of families of mentally ill adults. Psychiatric Services 48:1072–1074, 1997Google Scholar

9. Lehman A, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–20, 1998Google Scholar

10. Lehman A, Kreyenbuhl R, Buchanan R, et al: The schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–217, 2004Google Scholar

11. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1997Google Scholar

12. McEvoy J, Scheifler P, Francis A: The expert consensus guidelines series: treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 11):8–80, 1999Google Scholar

13. Mingyuan Z, Heqin Y, Chendge Y, et al: Effectiveness of psychoeducation of relatives of schizophrenic patients: a prospective cohort study in five cities of China. International Journal of Mental Health 22:47–49, 1993Google Scholar

14. Dixon L, Adams C, Lucksted A: Update on family psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:5–20, 2000Google Scholar

15. Dixon L, Lehman A: Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:631–643, 1995Google Scholar

16. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 59:903–910, 2001Google Scholar

17. McFarlane WR, McNary S, Dixon L, et al: Predictors of dissemination of family psychoeducation in community mental health centers in Maine and Illinois. Psychiatric Services 52:935–942, 2001Google Scholar

18. Pollio DE, North CS, Osborne VA: Family-responsive psychoeducation groups for families with an adult member with mental illness: pilot results. Community Mental Health Journal 38:413–421, 2002Google Scholar

19. Pickett-Schenk SA: Family education and support: just for women only? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:131–139, 2003Google Scholar

20. Dixon L, Lucksted A, Stewart B, et al: Outcomes of the peer-taught 12-week family-to-family education program for severe mental illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109:207–215, 2004Google Scholar

21. Pickett SA, Cook JA, Laris A: The Journey of Hope: An Evaluation of the National Journey of Hope Family Education and Support Program. Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago, National Research and Training Center on Psychiatric Disability, 1997Google Scholar

22. Pickett-Schenk SA, Cook JA, Laris A: Journey of Hope program outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal 36:413–424, 2000Google Scholar

23. Dixon L, Stewart B, Burland J, et al: Pilot study of the effectiveness of the Family-to-Family education program. Psychiatric Services 52:956–967, 2001Google Scholar

24. Pickett-Schenk SA, Cook JA, Steigman P, et al: Psychological well-being and relationship outcomes in a randomized study of family-led education. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:1043–1050, 2006Google Scholar

25. Pickett-Schenk SA, Bennett C, Cook J, et al: Changes in caregiving satisfaction and information needs among relatives with mental illness: results of a randomized evaluation of a family-led education intervention. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 76:545–553, 2006Google Scholar

26. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

27. Pollio DE, North CS, Osborne V, et al: The impact of psychiatric diagnosis and family system relationship on problems identified by families coping with a mentally ill member. Family Process 40:199–209, 2001Google Scholar

28. Salzer M, Shear SL: Identifying consumer-provider benefits in evaluations of consumer-delivered services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25:281–288, 2002Google Scholar

29. Solomon P: Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:392–401, 2004Google Scholar

30. Doornbos MM: Family caregivers and the mental health care system: reality and dreams. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 16:39–46, 2002Google Scholar

31. Rose L: Benefits and limitations of professional-family interactions: the family perspective. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 12:140–147, 1998Google Scholar

32. Biegel DE, Song L, Milligan SE: A comparative analysis of family caregivers' perceived relationships with mental health professionals. Psychiatric Services 46:477–482, 1995Google Scholar

33. Posner CM, Wilson KG, Kral MJ, et al: Family psychoeducational support groups in schizophrenia. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 62:206–218, 1992Google Scholar