Incarceration Rates of Persons With First-Admission Psychosis

Many deinstitutionalized persons with mental illness live in communities that were unprepared to receive them and that have inadequate mental health services and housing resources ( 1 ). Thus quality of life for many people with chronic psychopathology is characterized by poverty, unemployment, welfare dependency, inadequate public service access, homelessness, inpatient recidivism, and correctional facility placement ( 2 , 3 , 4 ). Amidst this list of adversities, incarceration has received much recent attention, perhaps because incarceration's objective of punishment stands in sharp contrast with the rehabilitation and empowerment goals of mental health interventions.

Correctional facility placement has become so pervasive that the rate of mental illness in prisons is two to four times greater than that in the general population ( 5 , 6 ). Although it is well known that many prisoners have mental illness, empirical data on incarceration of persons with severe psychopathology are scarce. The few existing studies that focus on mental health service recipients instead of inmates are largely cross-sectional in design ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ). In addition, prospective studies ( 13 , 14 ) of persons with serious mental illness were often undertaken in locations such as Australia or Finland where findings may not generalize to the United States, and they fail to adjust for incarceration history, despite its preeminence as a determinant of future jail stay ( 15 ). Taken together, the studies show that arrest or incarceration of persons with schizophrenia often follows trespassing, theft, property destruction, assault, battery, drug possession, or drug sales. Risk factors for becoming involved in the criminal justice system include poverty, male gender, minority status, unemployment, homelessness, substance abuse, intervention nonadherence, and prior incarceration.

However an important question remains unanswered in the literature on persons in the U.S. mental health system who are hospitalized for the first time and later go to jail. Which clinical and demographic characteristics best predict incarceration after adjusting for incarceration history and other potential influences?

Using data from the Suffolk County Mental Health Project (SCMHP), a prospective cohort study of first-admission patients with psychosis, we examined the incarceration rate over the four-year period after admission and demographic and clinical risk factors. We compared respondents with schizophrenia with those with other disorders because schizophrenia is relatively more prevalent than other psychosis types among jail inmates ( 9 ), and we hypothesized that risk of incarceration is greater among blacks than among whites because of social disadvantage ( 16 ). On the basis of research by Steadman ( 15 ), we also hypothesized that incarceration history would predict future jail admission to a greater extent than demographic and clinical variables. To our knowledge, although substance abuse has been examined before, this report represents the first evaluation of an array of clinical and demographic risk factors in a longitudinal investigation of individuals diagnosed as having a severe psychiatric disorder in relation to incarceration after their first psychiatric hospitalization.

Methods

Design

The SCMHP is described in detail elsewhere ( 12 ). Briefly, first-admission patients ages 15 to 60 who were residents of Suffolk County, New York, (population 1.3 million) were included in the study if they had psychotic symptoms. The head nurse, social worker, or project staff recruited them from 12 inpatient facilities between September 1989 and December 1995 (baseline response rate of 72%). Facilities included six 20- to 30-bed community hospital units, a 30-bed university hospital unit, a Veterans Affairs hospital, the state adult and child psychiatric centers, and two private hospitals (added in 1994). Exclusion criteria were a psychiatric hospitalization at any point more than six months before the current admission, moderate or severe mental retardation, inability to speak English, and inability to provide informed consent.

Procedures for obtaining written informed consent were approved annually by Committees on Research Involving Human Subjects at Stony Brook University and by institutional review boards of all hospitals where respondents were recruited. Written informed consent to all study procedures was first obtained from parents for respondents aged 15 to 17 years. Signed releases for hospital and clinic records were obtained at each face-to-face follow-up assessment, although this was not a requirement for participation.

Baseline interviews occurred primarily in the hospital. Follow-up interviews took place in participants' homes at six, 24, and 48 months; by phone every three months from baseline to 24 months; and by phone every six months from 24 to 48 months. In addition to standardized rating scales (see below), baseline evaluation included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) ( 17 ) supplemented with questions about suicide, violence, and drug use. Final SCID symptom ratings were based on the interview and medical record review. Interval SCIDs were administered at the six- and 24-month face-to-face interviews; selected modules were administered at the 48-month interview. A team of psychiatrists formulated a DSM-IV study diagnosis at consensus conferences held after the 24-month assessment using all available information sources ( 18 ).

Sample

Of the 675 participants at baseline, 47 were subsequently removed from the study for methodological reasons—that is, they had had previous hospitalizations, were not residents of Suffolk County, or clearly did not have a psychotic illness. Of the remaining 628 participants, 39 had insufficient follow-up information to permit a 24-month diagnostic evaluation. Thus the target sample was composed of 589 members of the original cohort. From this sample, we selected 538 persons to participate in our study: 228 with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophreniform disorder and 310 participants with other psychotic disorders (251 had mood disorders with certain or uncertain psychotic features and 59 had other psychoses—brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, and psychosis not otherwise specified).

Measures

The SCMHP maintained an ongoing chronological record of jail experiences, defined as placement in any type of correctional facility regardless of duration. The database includes entry and exit dates for each incarceration, number of days in jail, and charges. Information for this database came from respondents, relatives, and independent monitoring of admissions to the Suffolk County jail by reviewing semiannually the jail admission records for study participants. Four variables were considered: reasons for incarceration, number of jail stays, total time in jail, and date of first incarceration. The maximum time to first incarceration was 1,642 days (4.5 years) because jail data were available for an additional six months after the 48-month follow-up.

The risk factors for incarceration included demographic characteristics—that is, sex, age at admission, ethnicity (black versus nonblack), education (12 or more years versus less than 12 years), and clinical factors. The clinical risk factors were directly or indirectly derived from the SCID and included age at psychosis onset, lifetime DSM-III-R diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence, violence against people or property upon admission, the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score for the best month in the year preceding index admission, and current symptom severity based on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) ( 19 ). We also assessed exposure to trauma before age 16 using information from the trauma module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview ( 20 ), although final judgments were made by project staff consensus. For more detail on trauma operationalization, see the study by Neria and colleagues ( 21 ). Briefly, youth trauma was defined as events involving harm or threat to physical integrity that would be markedly distressing to almost anyone, such as physical or sexual abuse, assault, molestation, rape, threat with a weapon, and kidnapping.

Analysis

We first compared the diagnostic groups on the independent variables included in the analysis and on prevalence and incidence rates of posthospital incarceration. To examine associations of demographic and clinical risk factors with incarceration, three logistic regression models were estimated separately for each set. Model 1 examined independent effects of risk factors on incarceration, adjusting only for diagnosis (schizophrenia versus nonschizophrenia). Schizophrenia was controlled for a priori because among persons in jail, schizophrenia is overrepresented compared with other psychotic disorders ( 9 ). Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. Model 2 was a multivariate analysis that included all risk factors in the set. Model 3 extended model 2 by adding preadmission incarceration. Because preadmission incarceration was expected to have the strongest effect on postadmission incarceration, we included it only in the final model.

Logistic regression was also used to assess the clinical risk factors for posthospital incarceration among persons with a prehospital incarceration history and to assess such risk factors for those without such a history. For continuous variables (GAF scores, BPRS scores, age at psychosis onset, and admission age), analysis of variance with Scheffé's post hoc test was used to assess clinical and demographic differences between individuals with pre- and posthospital incarceration, individuals with pre- but without posthospital incarceration, individuals without pre- but with posthospital incarceration, and individuals without pre- or posthospital incarceration. Chi square analysis assessed differences between these four groups in relation to gender, high school education, black ethnicity, diagnosis of schizophrenia, violence upon hospital admission, youth trauma, and substance abuse.

In addition, we used the Kaplan-Meier technique to plot survival curves and used log-rank tests to compare differences in time to initial posthospital incarceration in relation to persons with versus without incarceration history before hospital admission and in relation to blacks versus nonblacks. The Cox proportional hazards model with a forward stepwise selection of variables was used to analyze time-to-incarceration data in order to underscore association of selected clinical and demographic variables with time to incarceration after adjusting for appropriate covariates. Criteria for model entry and removal were p<.05 and p<.10, respectively. Variables did not violate the proportional hazards assumption.

Results

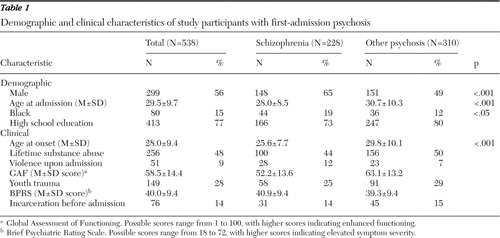

Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Most participants were white (405 participants, or 75%); 80 (15%) were black, 38 (7%) were Hispanic, and 15 (3%) were from another racial or ethnic group. Most had graduated from high school and were hospitalized for the first time between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Respondents with schizophrenia had an initial psychosis episode at a younger age than individuals with other psychotic disorders. Most had symptoms and functioning levels in the midrange of the GAF scale and the BPRS, and about half had substance abuse problems. About one in four participants had experienced youth trauma, and one in ten were violent upon hospital admission. One in seven had an incarceration history before the initial hospital admission.

|

A total of 47 persons (9%) were incarcerated during the four-year follow-up, including 19 of the 228 (8%) with schizophrenia and 28 of the 310 (9%) with other psychotic disorders. The four-year incidence rate of incarceration for respondents with no preadmission incarceration was 5% for the full sample (22 of 462 respondents), 6% for those with schizophrenia (12 of 197 respondents), and 4% for those with other psychotic disorders (ten of 265 respondents). Thus there were no substantial differences by diagnosis in incarceration rates over the four-year period.

Incarceration events, reasons, and time served

Of the 47 persons incarcerated after discharge, 27 (57%) had one jail stay, seven (15%) had two jail stays, six (13%) had three jail stays, and seven (15%) had four or more jail stays. Many of the participants were incarcerated for multiple reasons. Reasons for incarceration related most frequently to criminal mischief, such as trespassing (19 persons, or 40%); substance abuse, including driving while intoxicated, drug possession, and drug sales (17 persons, or 36%); violence (16 persons, or 34%); theft or burglary (14 persons, or 30%); and robbery (11 persons, or 23%). Number of incarcerations for drug possession differed between persons with schizophrenia (none with this offense) and respondents with other psychotic disorders (N=10) ( χ2 =8.6, df=1, p<.01).

A majority of incarcerated study participants spent 90 days or fewer in jail during the follow-up (30 of 46 persons, or 65%; data on jail time were missing for one person). Almost a quarter of detained individuals were in jail for only a day (11 of 46 persons, or 24%), and almost a fifth were in jail for over a year (eight of 46 persons, or 17%). The latter included two persons (4%) who were prisoners for more than two years. Total time in jail differed between persons with schizophrenia (mean±SD=80±169 days) and those with other psychotic disorders (mean=212±312 days) (t=1.64, df=44, p<.05).

Incarceration of persons without a history of jail stay

Among the 462 persons without an incarceration history, very few differences were found between respondents who went to jail for the first time after the initial hospitalization (N=22) and those who remained out of jail (N=440). Persons without an incarceration history were more likely to be male than female (18 of 238 males, or 8%, compared with four of 224 females, or 2%) (OR=4.5, CI=.50–13.51, p<.01) and less likely to have graduated from high school (ten of 103 persons who did not graduate, or 10%, compared with 12 of 359 persons who did graduate, or 3%) (OR=3.11, CI=1.30–7.42, p<.01).

Incarceration of persons with a history of jail stay

However, in relation to the 76 persons who had been to jail before their first hospitalization (including 25 with and 51 without posthospital incarceration), blacks were more likely than nonblacks to be incarcerated at follow-up (14 of 23 blacks, or 61%, compared with 11 of 53 nonblacks, or 21%) (OR=5.94, CI=2.04–17.29, p< .001), as were persons who were violent upon hospital admission (six of nine persons who were violent, or 67%, compared with 19 of 67 persons who were nonviolent, or 28%) (OR=5.88, CI=1.32–26.13, p<.05).

Given variation in risk factors related to the presence or absence of incarceration history, an analysis of variance assessed differences between the four groups of respondents with and without pre- and posthospital incarceration. Persons with pre- and posthospital incarceration had lower GAF scores than individuals without jail time either before or after the hospital stay (mean score of 48.48±13.63, compared with a mean score of 59.55±14.34) (F=6.21, df=3 and 534, p<.001). Clear patterns did not emerge in relation to additional between-group differences, although ethnicity findings were consistent with those shown in subsequent tables and figures.

Multivariate prediction of incarceration

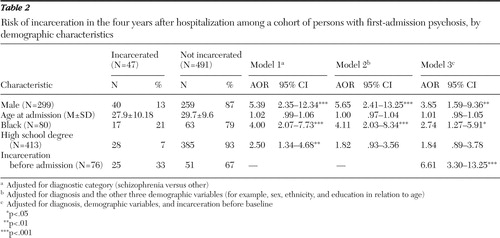

Among the demographic characteristics ( Table 2 ), three factors significantly elevated incarceration risk after the analysis adjusted for diagnosis: male gender, black race, and lack of a high school degree (model 1). Gender and race-ethnicity remained significant after adjustments were made for all demographic variables (model 2). As anticipated, incarceration before hospitalization was the strongest predictor of incarceration after hospitalization (OR=9.80, CI=5.16–18.63, p<.001). Thus in model 3 incarcerated respondents were more than six times as likely to have been incarcerated before hospitalization, almost three times as likely to be black, and almost four times as likely to be male.

|

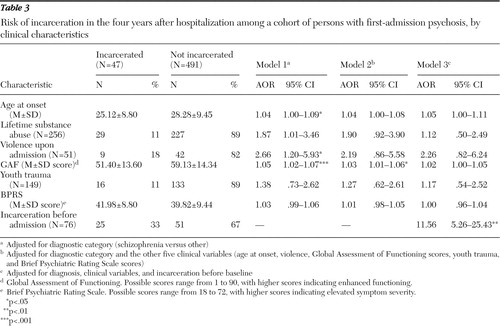

As shown in Table 3 , three of the six clinical predictors were significantly associated with incarceration after the analysis adjusted for diagnosis: age of psychosis onset, violence upon admission, and GAF scores (model 1). When all clinical predictors except for prehospital incarceration were considered together in a single model (model 2), violence upon admission and age at onset were no longer significant. After adding prehospital incarceration (model 3), only prior jail stay was significant.

|

Time to incarceration

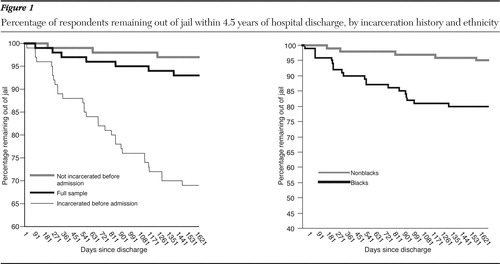

Among study participants with postbaseline incarceration, average time from admission to first jail entry was about 22 months (mean of 668±449 days, median of 582 days, and interquartile range of 280–1,061 days). It did not differ between persons with schizophrenia (mean of 667±478 days, median of 670 days, and interquartile range of 342–1,173 days) and those with other psychotic disorders (mean of 669±478 days, median of 549 days, and interquartile range of 257–973 days). Average time before postbaseline detainment among persons with a prebaseline incarceration history (23 persons with pre- and postjail time) was about 26 months for study participants with schizophrenia (mean of 794±414 days, median of 694 days, and interquartile range of 360–1,176 days) and 19 months for those with other psychotic disorders (mean of 584±422 days, median of 572 days, and interquartile range of 257–897 days). Data on jail reentry time were missing for ten participants. Figure 1 shows survival curves over the four-year follow-up for all respondents, those incarcerated before admission, and those not incarcerated before admission. Compared with participants without an incarceration history, persons with an incarceration history were detained more steadily and rapidly ( χ2 =86.02, df=1, p<.001).

In addition, as shown in Figure 1 , incarceration hazard after hospital admission was significantly greater for black respondents than for nonblack respondents ( χ2 =27.29, df=1, p<.001).

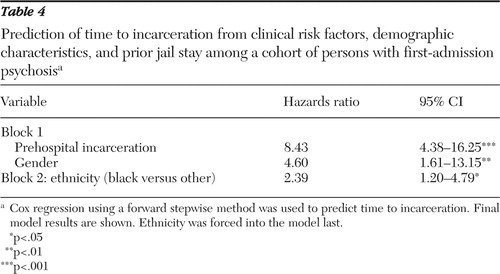

Findings from the final Cox regression model are shown in Table 4 . Results followed a pattern similar to those in Tables 2 and 3 , because among the 12 independent variables (six clinical risk factors, four demographic factors, diagnosis of schizophrenia versus other, and prehospital incarceration), only gender, ethnicity, and prior jail stay remained statistically significant and were selected for the final model. Consistent with findings shown in Tables 2 and 3 , Table 4 shows that persons with a prior incarceration were more than eight times as likely as their counterparts without an incarceration history to go to jail, males were almost five times as likely as females to go to jail, and black persons were more than twice as likely as nonblack persons to go to jail.

|

Discussion

Similar to the finding by Munetz and colleagues ( 9 ), about 9% of study participants were incarcerated within four years of the initial psychiatric hospital admission for psychosis. Of them, 43% were placed in jail more than once, typically within one to two years. And although almost a quarter (24%) of detained persons spent only a day in jail, only a few less (17%) were held for over a year. Despite the fact that schizophrenia is relatively more prevalent than other psychosis types among jail inmates ( 9 ), incarceration prevalence, incidence, and time to incarceration did not vary by psychopathology type in this study, nor did common incarceration reasons of criminal mischief (for example, trespassing), theft, burglary, robbery, and violence. Persons with schizophrenia were less likely to be held for drug possession than respondents with other psychotic disorders.

Before discussing the findings, it is important to acknowledge study limitations. Although the sample was reasonably large and representative of patients from Suffolk County, it was nonetheless restricted to residents who were hospitalized in a facility located within the county. Hence it is not a complete incidence sample per se, and we do not have information on individuals who were hospitalized outside the county. Although we had information from the Suffolk County jail, we could not supplement information from self-report and from relatives with data from jail and prison sources outside of Suffolk County. Hence we no doubt underenumerated actual jail experiences. There is no indication that the underenumeration was differentially associated with diagnosis or with any of the risk factors. However, underreporting is a potential study weakness.

In addition, the sample size did not permit separate analysis of incarcerated persons with specific disorders other than schizophrenia—for example, unipolar versus bipolar disorder or presence of co-occurring conditions, such as psychopathy. Furthermore, respondents who were unavailable for follow-up may have had different incarceration rates or risk factors or differed in other ways from respondents who remained in the study. Finally and perhaps most important, study participants were selected nonrandomly from a single geographic location. Thus the findings may not generalize to locations with differing levels or types of diversity, tolerance, or social disadvantage for minority group members or community hardship related, for example, to unemployment or poverty.

Study results are consistent with pioneering research by Steadman ( 15 ), because our study showed that incarceration history best predicted future jail stay and time to incarceration among persons with first-admission psychosis, even after considering influence of disorder type (schizophrenia versus other psychotic disorder) and a variety of other clinical characteristics. Black ethnicity emerged as a highly significant determinant as well. Less powerful influences included substance abuse, low functioning levels, violence upon hospital admission, and early age of psychosis onset. Although other studies suggest that these three factors may be either directly or indirectly related to jail stay ( 14 , 15 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ), our study suggests that the impact is limited.

The influence of substance abuse on incarceration is well documented ( 7 , 13 , 14 , 32 , 34 ); yet in this study it only approached statistical significance and only in the absence of other factors. Reasons why this finding diverges from prior studies are not entirely clear. However, the two factors that dwarfed influence of substance abuse in this study—ethnicity and incarceration history—have been largely unexamined in most longitudinal investigations of persons with serious psychopathology ( 13 , 14 ). Perhaps researchers overlook these two factors because they are already known to contribute to incarceration risk. The connection could seem obvious, in other words, or mask influence of other determinants; yet including them is a better way to assess incarceration vulnerability. Focusing on substance abuse or other potential risk factors such as psychopathology type or severity, for example, is misleading if the influence is small in relation to minority group membership or prior jail time and can result in undue emphasis on clinical rather than contextual concerns (especially criminal justice system involvement, oppression, and social disadvantage). Among persons without an incarceration history, however, it is noteworthy that the best incarceration predictor in this study was level of functioning on the GAF scale.

The ethnicity-related finding is alarming but perhaps not surprising, because black people in the general population are more than 5.5 times as likely as white people to be placed in jail ( 6 ). It therefore seems likely that a similar minority overrepresentation occurs among persons with psychosis, especially because many have lived in communities with abundant poverty, high unemployment rates, and limited public service access ( 2 ). Social disadvantages such as these increase vulnerability for jail stay ( 16 ), especially when combined in many locations with high levels of race-based oppression. Accordingly, ethnicity emerged as a highly significant risk factor for both incarceration and time to the first detention. Compared with whites, blacks were more than twice as likely to be placed in penal institutions and were incarcerated sooner after the first admission, even after adjusting for prior jail stay and other demographic characteristics.

This finding emphasizes the need for mental health and criminal justice system professionals to address racism and community hardship related, for example, to reduced economic opportunity for blacks in the labor market and housing ( 35 , 36 ). Indeed, these contextual factors most likely increase incarceration risk to a greater extent than presence of psychopathology, as noted by Draine and colleagues ( 16 ). Failure to focus on social disadvantage has negative consequences in both practice and research. It causes investigators to overemphasize clinical influences of substance abuse, mental illness, or youth trauma and limits the scope and impact of jail diversion or other incarceration prevention programs.

In addition to pursuit of social change, results suggest that black people and people with an incarceration history should be targeted for interventions designed to avert correctional facility placement ( 37 ), especially if other risk factors are present. Prevention can include assertive community treatment, mobile services after discharge, residential care, and enhanced collaboration between the criminal justice system and mental health professionals in mental health courts or jail diversion teams, for example. Less intensive efforts can include calls or visits to residences and family involvement in care.

However these interventions were not designed specifically for blacks in outpatient care. For them, mental health and criminal justice system staff can enhance use of mutual assistance. Self-help has been shown to reach blacks—an important consideration given the likelihood of this group's being underserved in community mental health care ( 38 ) and overrepresented in hospital or crisis-based assistance ( 39 ). Evidence suggests that black people use mutual assistance more often than white people, perhaps as an alternative to traditional outpatient services ( 11 ), and that mutual assistance enhances mental health and prevents arrest ( 40 , 41 , 42 ). In pursuit of these goals, policy is needed that increases partnership between jail diversion teams and self-help agencies or that creates specialized mutual assistance programs for individuals with both psychopathology and an incarceration history ( 43 ).

Future studies using larger and more diverse samples of persons with serious psychopathology could beneficially examine incarceration in relation to neighborhood effects and ethnicity differences other than black versus nonblack. Studies could also provide greater elucidation of interdiagnostic differences and substance abuse co-occurrence; peer, family, and professional intervention; outpatient intervention adherence and incarceration risk; and housing type and homelessness. In addition, researchers could examine how incarceration can lead to hospitalization or homelessness, and vice versa, and identify subgroups of incarceration trajectories using latent class growth analysis. Finally, differences between persons with multiple prior hospitalizations and first-admission psychosis could be beneficially explored.

Conclusions

Although less than 10% of persons with first-admission psychosis were incarcerated within four years, a significant number were jailed repeatedly or held for over a year. Very few incarceration differences were found between persons with schizophrenia and those with other psychotic disorders. Prior jail stay best predicted future incarceration and time to incarceration after the analysis accounted for influence of demographic and clinical characteristics, and black race was also highly influential. Less powerful incarceration determinants included substance abuse, limited functioning, violence upon psychiatric hospital admission, and early age of psychosis onset. The ethnicity-related finding underscores the need to address racial oppression and social disadvantage, and first-admission patients who are at risk should be targeted for services designed to prevent jail stay before further entrenchment in mental health and criminal justice systems. Mental health professionals should routinely evaluate, document, and collaboratively address incarceration history, especially when working with black males or when other risk factors are present.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported in part by grant 4481 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Kimberly J. Hornak, M.S.W., for compiling the data, John R. Bowblis, M.A., for his statistical consultation, and staff and respondents of the Suffolk County Mental Health Project.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Segal SP: Deinstitutionalization, in Encyclopedia of Social Work, 19th ed. Edited by Edwards RL. Washington, DC, NASW Press, 1995Google Scholar

2. Grob GN: The paradox of deinstitutionalization. Society 32:51–68, 1995Google Scholar

3. Lamberti JS: New approaches to preventing incarceration of severely mentally ill adults. Psychiatric Times 21:1–9, 2004Google Scholar

4. Mechanic D, Rochefort DA: Deinstitutionalization: an appraisal of reform. Annual Review of Sociology 16:301–327, 1990Google Scholar

5. Ditton P: Mental Illness and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 1999Google Scholar

6. Human Rights News: United States: Mentally Ill Mistreated in Prison: More Mentally Ill in Prison Than in Hospitals. New York, Human Rights Watch, 2003. Available at www.hrw.org/press/2003/10/us102203.htmGoogle Scholar

7. Clark GN, Herinckx HA, Kinney RF, et al: Psychiatric hospitalizations, arrests, emergency room visits and homelessness of clients with serious and persistent mental illness: findings from a randomized trial of two ACT programs vs usual care. Mental Health Services Research 2:155–164, 2000Google Scholar

8. McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA: Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:42–48, 2004Google Scholar

9. Munetz MR, Grande TP, Chambers MR: The incarceration of individuals with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 37:361–372, 2001Google Scholar

10. Quanbeck CD, Stone DC, McDermott BE, et al: Relationship between criminal arrest and community treatment history among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 56:847–852, 2005Google Scholar

11. Theriot MT, Segal SP, Cowsert MJ Jr: African-Americans and comprehensive service use. Community Mental Health Journal 39:225–237, 2003Google Scholar

12. Bromet EJ, Naz B, Fochtmann LJ, et al: Long-term diagnostic stability and outcome in recent first-episode cohort studies of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 31:639–649, 2005Google Scholar

13. Tiihonen J, Isohanni M, Rasanen P, et al: Specific major mental disorders and criminality: a 26-year prospective study of the 1966 Northern Finland birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:840–845, 1997Google Scholar

14. Wallace C, Mullen PE, Burgess P: Criminal offending in schizophrenia over a 25-year period marked by deinstitutionalization and increasing prevalence of comorbid substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:716–727, 2004Google Scholar

15. Steadman HJ: A new look at recidivism among Patuxent inmates. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 5:200–209, 1977Google Scholar

16. Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–573, 2002Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Archives of General Psychiatry 49:624–629, 1992Google Scholar

18. Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, et al: Congruence of diagnoses 2 years after a first admission diagnosis of psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:593–600, 2000Google Scholar

19. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Google Scholar

20. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Epidemiological risk factors for trauma and PTSD, in Risk Factors for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Edited by Yehuda R. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1999Google Scholar

21. Neria Y, Bromet EJ, Sievers S, et al: Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in psychosis: findings from a first-admission cohort. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 70:246–251, 2002Google Scholar

22. Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al: Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:979–986, 2006Google Scholar

23. Carlson GA, Bromet EJ, Driessens C, et al: Age at onset, childhood psychopathology, and 2-year outcome in psychotic bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:307–309, 2002Google Scholar

24. DeLisi LE: The significance of age of onset for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 18:209–215, 1992Google Scholar

25. Dernovsek MZ, Tavcar R: Age at onset of schizophrenia and neuroleptic dosage. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:622–626, 1999Google Scholar

26. Engstrom C, Brandstrom S, Sigvardsson S, et al: Bipolar disorder II: personality and age of onset. Bipolar Disorder 5:340–348, 2003Google Scholar

27. Hiday VA, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al: Victimization: a link between mental illness and violence? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 24:559–572, 2002Google Scholar

28. Joyce E: Origins of cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: clues from age at onset. British Journal of Psychiatry 186:93–95, 2005Google Scholar

29. Kennedy N, Boydell J, Kalidindi S, et al: Gender differences in incidence and age at onset of mania and bipolar disorder over a 35-year period in Camberwell, England. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:257–262, 2005Google Scholar

30. Meeks S: Bipolar disorder in the latter half of life: symptom presentation, global functioning and age of onset. Journal of Affective Disorders 52:161–167, 1999Google Scholar

31. Mick E, Biederman J, Faraone SV, et al: Defining a developmental subtype of bipolar disorder in a sample of nonreferred adults by age at onset. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 13:453–462, 2003Google Scholar

32. McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC: Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 56:840–846, 2005Google Scholar

33. Swanson J, Borum R, Swartz M, et al: Violent behavior preceding hospitalization among persons with severe mental illness. Law and Human Behavior 23:185–204, 1999Google Scholar

34. Hartwell S: An examination of racial differences among mentally ill offenders in Massachusetts. Psychiatric Services 52:234–236, 2001Google Scholar

35. Corcoran M: Mobility, persistence, and the intergenerational determinants of children's success. Focus 21:16–20, 2000Google Scholar

36. Yinger J: Housing discrimination and residential segregation as causes of poverty. Focus 21:51–55, 2000Google Scholar

37. Lamberti JS, Weisman DO, Faden DI: Forensic assertive community treatment: preventing incarceration of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:1285–1293, 2004Google Scholar

38. Sohler NL, Bromet EJ, Lavelle J, et al: Are there racial differences in the way patients with psychotic disorders are treated at their first hospitalization? Psychological Medicine 34:705–718, 2004Google Scholar

39. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo J, Powe N, et al: Mental health service utilization by African Americans and whites: the Baltimore Epidemiological Catchment Area follow-up. Medical Care 37:1034–1045, 1999Google Scholar

40. Hardiman ER, Segal SP: Community membership and social networks in mental health and self-help agencies. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:25–33, 2003Google Scholar

41. Hatzidimitriadou E: Political ideology, helping mechanisms and empowerment of mental health self-help/mutual aid groups. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 12:271–285, 2002Google Scholar

42. Moos R, Schaefer J, Andrassy J, et al: Outpatient mental health care, self-help groups, and patients' one year treatment outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology 57:273–287, 2001Google Scholar

43. Prince JD: Incarceration and hospital care. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 194:34–39, 2006Google Scholar