Consistency of Psychiatric Crisis Care With Advance Directive Instructions

Psychiatric advance directives document clients' treatment preferences in advance of periods of diminished capacity for decision making. Psychiatric advance directives may include preferences about medications, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), restraint and seclusion, hospitalization, methods of deescalating crises, alternatives to hospitalization, persons to contact regarding care of dependents and household, and appointment of a surrogate decision maker ( 1 , 2 , 3 ).

Potential benefits of using psychiatric advance directives, such as increased treatment collaboration, expedited crisis care, and reduced psychiatric hospitalizations ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ), are more likely to be realized if care is consistent with directive instructions, although patients may experience an increased sense of procedural justice by simply having their directive considered even if instructions ultimately are not followed. The literature regarding health care advance directives shows that their instructions are not consistently followed. A recent study ( 10 ) found that physician decisions were inconsistent with advance directive instructions in 65% of cases. Earlier studies showed that although care was consistent with previously expressed do-not-resuscitate (DNR) requests 75% of the time ( 11 ), only about half of physicians accurately reported patients' DNR instructions. These findings have led some to conclude that advance directives are "irrelevant to decision making" ( 12 ). Some worry that psychiatric advance directives will be regarded in this way and that client frustration will result.

Health care advance directives often are not followed when family members or surrogate decision makers disagree with instructions, particularly in regard to withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ). It is unclear whether surrogate decision makers will exert the same influence on psychiatric advance directives, which guide only temporary crisis treatment.

Care is more likely to be consistent with health care advance directives in a hospital rather than in a nursing home setting and when a patient remains competent ( 11 ). Instructions perceived by a physician to be inappropriate may be less likely to be followed ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ). Moreover, laws pertaining to psychiatric advance directives typically permit instructions to be overridden when they conflict with practice standards or emergency treatment or if the treatment requested is not feasible or available (www.nrc-pad.org).

For care to be consistent with directive instructions, clinicians must first access the documents. We have found in earlier analyses that directives are accessed in only about 20% of crisis events. Directives are more likely to be accessed within a treatment system for clients with repeated crises, fewer outpatient commitment orders and hospitalizations, and no substance use and when someone, especially an appointed surrogate decision maker, is involved during the psychiatric crisis (Srebnik D, Russo J, unpublished manuscript, 2007). Once a directive is accessed it is unknown whether these factors are also related to consistency of care with directive instructions.

This article provides the first empirical data regarding the rate and predictors of receiving care that is consistent with psychiatric advance directive instructions. We first present the frequency at which directive instructions were consistent with care during crisis events in which a directive was accessed. Then, predictors of care consistency with directives are examined, including demographic characteristics and clinical severity, individuals involved in the crisis, location of service, clinical utility of directive instructions, study site, and study period (time).

Methods

Participants and settings

Participants were enrolled in services at two community mental health centers in the state of Washington. The University of Washington's institutional review board approved participant selection and recruitment methods. Using electronic records, a pool of 475 potential participants were identified as meeting study criteria by being at least 18 years old and having at least two psychiatric emergency service visits or hospitalizations within the previous two years. Of those, 172 were ineligible for participation because of long-term hospitalization or incarceration (N=158), inability to provide informed consent (N=6) or participate in English (N=6), or agitation that prevented introduction to the study (N=2). Of the 303 eligible individuals, 106 went on to complete an advance directive. Detailed information regarding recruitment is presented elsewhere ( 17 ).

The sample included 58 women (55%), and the average age of participants was 41.9±9.1 years. A total of 25 persons were from ethnic and minority groups (24%). Almost half of the participants had a diagnosis of a primary axis I schizophrenia spectrum disorder (N=55, or 48%), and remaining individuals had a diagnosis of either bipolar disorder (N=28, or 26%) or a form of depression (N=27, or 26%). Nearly half (N=48, or 45%) of the sample had a secondary diagnosis of a substance use disorder. Over one-third had a diagnosis of an axis II personality disorder (N=39, or 37%), and five individuals (5%) had developmental disabilities. The average score on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale ( 18 ) was 31.1±9.13. Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning.

Procedures

Creation and dissemination of directives. Participants completed advance directives using AD-Maker software ( 19 ). Details of the process of completing directives and their resulting content and clinical utility are provided in other publications ( 20 , 21 ).

Copies of directives were provided to individuals selected by participants, for the participant's medical record, and to a centralized 24-hour crisis service. Participants were given a wallet card and dogtag-style necklace or identification bracelet noting the existence of a directive and where to access it. A data flag was added to the client's electronic community mental health service registry, viewable in emergency and hospital settings, to indicate whether a client had a directive. Outpatient, inpatient, and crisis service staff were trained on how to access directives.

Definition of psychiatric crisis and access to directives. Participants and their outpatient case managers were asked on a quarterly basis whether the client's advance directive had been used or whether there had been a hospitalization or contact with after-hours crisis services that could have triggered use of the directive. A psychiatric crisis was defined as either a positive response to these questions or an emergency service or hospitalization record in electronic medical records. To determine whether the directives had been accessed, for each crisis event both the participant and his or her case manager responded to the Directive Use Interview, and a chart review was conducted (see Measures section below). Directives were accessed in 20% of the 450 crisis events examined in the study.

Definition of care consistent with directive instructions. Whether care was consistent with instructions in the advance directives was examined only for relevant content areas during crisis events in which directives were accessed. Relevant content areas were defined as having directive instructions specified, evidence that the content area was an issue during the crisis (for example, medications were used or hospitalization was considered), and the intervention was available in the setting (for example, ECT was not typically available). A panel of three research team members jointly reviewed interview and chart review data (see Measures section) for each crisis event until consensus was reached to determine whether crisis care was consistent with directive instructions. Instructions were considered consistent with care regardless of evidence that the directive was actively considered when making treatment decisions.

For each of the 90 crisis events in which a psychiatric advance directive was accessed, the rate at which directive instructions were consistent with crisis care was calculated as the number of directive content areas consistent with care divided by the total number of relevant content areas. For example, if there were six relevant content areas during a given crisis event and three were consistent with care, a 50% consistency rate would result.

Measures

Directive Use Interview. The Directive Use Interview asked participants and their case managers whether the advance directive was used during the crisis and whether the following people were involved in the crisis and accessed the directive: family, friends, surrogate decision maker, case manager, other outpatient staff, and inpatient and emergency room staff. Information was coded as yes or as no or don't know. For each directive content area, respondents were asked whether interventions during the crisis were consistent with the directive instructions and if not, why not.

Chart review. Crisis service and hospital charts were reviewed to determine whether interventions were consistent with directive instructions.

Electronic patient information. In the past year and during the two-year study period we obtained the following information from participants' electronic medical records: demographic characteristics (age, ethnicity, and gender); psychiatric diagnosis; GAF score ( 18 ); and psychiatric hospitalizations, emergency services, and outpatient commitment orders. Ethnicity was dichotomized as white or nonwhite because of the small proportion of several of the groups of nonwhite participants. Primary axis I diagnoses were categorized as schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, and other diagnoses. Substance use disorders and axis II personality disorders also were documented. Information also identified the site of the patient's community mental health center.

Symptom severity and functioning were assessed with the Problem Severity Summary (PSS) and the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (PSAS). The PSS is a 13-item symptom and functioning assessment instrument designed for community mental health settings. It has shown adequate internal consistency, sensitivity to treatment change, and concurrent, predictive, and discriminant validity ( 22 ). The PSAS is a 23-item symptom severity scale, developed as a revision of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) ( 23 , 24 ). Interrater reliability of the PSAS is strong (intraclass correlation range of .62–.89 for all but one item).

Directive utility ratings. Directive content areas were rated on 3-point Likert scales regarding consistency with practice standards, feasibility, and usefulness ( 21 ). Ratings were based on experience with typical psychiatric crises because conducting the tests needed to collect ratings during actual psychiatric crises was unfeasible. Because of a lack of variance, the scales were recoded as dichotomous—consistent or inconsistent, feasible or unfeasible, and useful or not useful. Exact agreement was over 90% for all ratings, with the exception of instructions about willingness to try medications not listed in the directive (67%), ECT (73%), people not authorized to visit during hospitalization (70%), and other narrative instructions (73%).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with software packages SPSS 13.0 and Stata 7.0. Rates at which directive instruction content areas were consistent with care were derived in the manner described above.

The 90 crisis events in which directives were accessed were based on data from 35 individuals. Fifteen participants (43%) had one crisis event, 17 (49%) had between two and four crisis events, and three (9%) had more than four crisis events (that is, eight, eight, and 12 events). Because a given participant often accounted for more than one crisis event, clustered linear regression analyses with robust error estimation were used ( 25 ). Using univariate linear regressions, we determined the relationships between each independent variable and the rate of care consistent with directive instructions as the dependent variable for the 90 crisis events. We then calculated a final regression model, entering all independent variables with statistical significance of p<.15 into the model and removing one by one the most nonsignificant independent variables until only significant variables were retained in the final model.

Results

Consistency of care with directive instructions

Across all 90 crisis events in which an advance directive was accessed, the average number of relevant content areas out of 19 areas was 8.39±2.81. The average number of directive content areas that were consistent with care across the 90 events was 5.87±2.88. The average rate of care consistent with directive instructions was 67%±22%. Thus about two-thirds of directive instructions were consistent with crisis care.

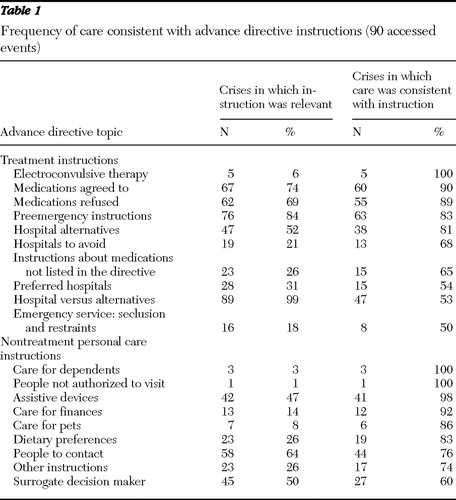

Directives in this study addressed ten treatment areas and nine nontreatment personal care areas ( Table 1 ). These content areas are ordered by decreasing rates of consistency with crisis care in Table 1 . The first set of columns in Table 1 shows the total number of crisis events for which the content area was relevant, and the percentage is this number divided by 90 crisis events. The second set of columns in Table 1 shows the number of times that care was consistent with content area of directives and the rate that this represents for the crisis events in which the content area was relevant.

|

Within treatment content areas, instructions regarding ECT, medications, preemergency deescalation methods, and hospital alternatives were consistent with care during nearly all crisis events in which the instructions were relevant. Preferences regarding hospitals, medications not specifically listed in the directive, use of hospitals or alternatives, and rank-ordered preferences among seclusion, restraint, and sedating medications were consistent with care somewhat less often.

Care was typically consistent with nontreatment instructions, although the number of crisis events in which these instructions were relevant was sometimes modest. An exception was for instructions to contact a surrogate decision maker, which was done in only 60% of crisis events.

Predictors of care consistency with directive instructions

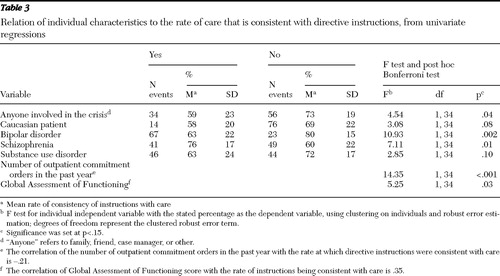

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the univariate analyses and present only the variables that were significantly related to the rate at which directives were consistent with care in the 90 crisis events. Variables that were individually tested but not found to be related to this rate (p<.15) were involvement of friends, other outpatient staff, or inpatient and emergency room staff in the crisis; treatment location (inpatient, emergency, or other); age; gender; having major depression or an axis II personality disorder; PSAS sum; PSS sum; number of hospitalizations during the prior year; directive utility; number of crisis events during the study period for a given client and events in which a directive was accessed; and study site and study quarter (time).

|

|

The univariate analyses revealed that involvement of a case manager, family member, and surrogate decision makers who accessed the psychiatric advance directive or were involved with the crisis was related to the rate at which care was consistent with directive instructions, at least at the trend level (p<.15) (see Table 2 ). When a case manager, family member, or surrogate had no role in the crisis, the proportion of content areas consistent with care ranged from 61% to 64%. When one of these individuals was involved in the crisis but did not access the directive, the proportion jumped to 72%–75%. When the individual was both involved in the crisis and accessed the advanced directive, the rate increased to 76%–84%.

Some individual characteristics were also related to the rate at which directive instructions were consistent with care ( Table 3 ). Crises for clients who were Caucasian, had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, had a diagnosis of a substance use disorder, and had higher GAF ratings had higher rates of instructions consistent with care. Crises for clients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and more outpatient commitment orders during the prior year showed lower rates of treatment that was consistent with advance directives.

A linear regression model using robust error estimation and clustering on the client was fit containing the ten variables mentioned above. After we individually removed the least significant variables, the final model contained two variables that were statistically significant. A higher rate of directive instructions consistent with care was found during crises for clients who had a lower number of prior outpatient commitment orders (B=-.05, t=-3.45, df=34, p=.002) and a surrogate decision maker who was both involved and who accessed the directive (B=.21, t=3.50, df=34, p=.001).

Reasons that care was not consistent with instructions

Clinical need, including the need for involuntary treatment, was the reason most commonly reported by case managers for care that was not consistent with directive treatment instructions. Also, clients often reported clinical need as a reason for inconsistency but noted their own change in preference as the top reason that hospital alternative instructions were not used. They also noted the lack of available beds as the reason for not being admitted to their preferred hospital and physicians' refusal to follow directive instructions as the primary reason for not using preemergency intervention preference instructions.

For nontreatment personal care issues, the most common reason that care was not consistent with directive instructions noted by both case managers and clients was that the issue (such as care of pets and finances) had already been taken care of.

Discussion

This study presented initial findings regarding the extent to which psychiatric advance directive instructions are consistent with crisis care. The data show that, when directives are accessed during crisis events, about two-thirds of psychiatric advance directive instructions are consistent with care. This rate is in the range found for health care advance directives ( 10 , 11 ).

Care was consistent with directive treatment instructions regarding medications, preemergency deescalation methods, and types of hospital alternatives in nearly all relevant crisis events. Care was consistent with instructions somewhat less often regarding individuals' choice of hospital, preferences between hospitals and alternatives to hospitalization, and preferences regarding seclusion, restraint, and sedating medication, perhaps because these issues are driven by factors other than client preference, such as resource availability, regulations, and practice guidelines.

Nontreatment personal care instructions were generally consistent with care, with the exception of contacting a surrogate decision maker, which was done in only 60% of crisis events. This is a troubling finding and suggests the need for training and advocacy.

We note a number of study limitations. First, the study examined only whether clinical interventions were consistent with directive instructions. Data were not available about whether directives were actively considered when making treatment decisions. Analysis was limited, however, to crises in which directives were accessed—in other words, those events in which it was at least possible for directive instructions to be considered. Although our analyses revealed some variables that were associated with whether care is consistent with directive instructions, whether and how directives are considered during actual crises events need to be examined in more detail and would be a fruitful area for further research.

More detailed research during crisis events could also specify the extent to which an individual was considered incapacitated or unable to make treatment decisions. Psychiatric advance directives are designed for use during periods when an individual is considered incapacitated or unable to make treatment decisions; however, we were unable to collect this information in this study.

Our results should also be viewed in light of limiting analysis to crisis events in which directives were accessed. As noted earlier, directives were accessed in only 20% of the psychiatric crisis events. Although about two-thirds of directive instructions were consistent with care during events in which directives were accessed, we do not know whether this rate would change if directives were accessed in a larger proportion of crisis events and if those events were subject to analysis.

Surrogate decision makers who were involved during a client's crisis and who accessed a directive increased the likelihood that care would be consistent with directive instructions. The relationship between surrogate involvement and following directive instructions may be related to some unmeasured third variable, such as social functioning or ability to communicate effectively with treatment providers. Suggestive of this possibility is our finding that clients with fewer prior outpatient commitment orders (a proxy for treatment engagement) were more likely to have care consistent with directive instructions. Other clinical severity variables were unrelated to whether care was consistent with directive instructions. Our prior work has shown that both involvement of a surrogate decision maker and fewer prior outpatient commitment orders also increase the likelihood that directives are accessed to begin with. In contrast, for health care advance directives, surrogate decision-maker involvement can decrease the likelihood that directives are followed. Perhaps surrogates are reluctant to concur with irreversible life-and-death choices that their loved ones previously expressed and are more comfortable concurring with psychiatric advance directive instructions that guide temporary crisis treatment. In our study, of 17 surrogate decision makers we reached for interviews, 11 (65%) responded that they completely agreed with the directive, and an additional four (24%) agreed only somewhat.

A few variables that were hypothesized to be related to having care consistent with directive instructions were not related. Physician-rated utility of directive instructions was unrelated to whether care matched instructions. In a previous article, we have shown that nearly all directive instructions are rated as clinically useful and feasible ( 25 ), and this attenuated distribution likely reduced the chance of finding an effect. That said, our findings should lessen concerns over whether directive instructions are useful enough to be considered in making treatment decisions. We have also found that repeated crises by clients and study period (time) were significant predictors of accessing directives; however, these variables were not significantly related to whether care was consistent with directive instructions once the document was accessed.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that to increase the likelihood that care will be consistent with psychiatric advance directive instructions, having a surrogate decision maker is desirable. Our earlier work has shown that only about half of persons who create psychiatric advance directives appoint a surrogate decision maker ( 21 ), and this study shows that surrogates are involved in only 31% of crisis events in which directives are accessed. As such, clients would be well advised to appoint a surrogate decision maker, particularly one who could be actively involved during crisis events. For clients without local family or friends to serve as a surrogate decision maker, a trained peer could function in this role or as a more informal advocate for directives. Someone who can faithfully interpret and advocate for a client's wishes can be invaluable, even if that person has no legal standing as a surrogate decision maker ( 12 , 14 , 15 ).

The most commonly reported reason for care that does not match directive treatment instructions was clinical need, including the need for involuntary treatment. Although directive instructions are clinically useful and feasible in general, instructions may not always adequately address clinical needs during specific crisis events. Laws regarding advance directives anticipated the need to override directives for involuntary and emergency treatment. Statutes also permit overriding directives if treatment requested is not consistent with practice standards or is unfeasible or unavailable; however, respondents very infrequently reported these reasons for care as not matching directive instructions.

Overall, we found that when psychiatric advance directives are accessed, care is likely to be consistent with their instructions. Having someone involved in the crisis, particularly a surrogate decision maker, increases this likelihood. As such, encouraging creation and use of directives could be viewed as a positive step in the process of recovery and as an additional method of communicating client preferences during psychiatric crises.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This project was supported by grant R01-MH58642 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Appelbaum P: Advance directives for psychiatric treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:983–984, 1991Google Scholar

2. Srebnik D, LaFond J: Advance directives for mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services 50:919–925, 1999Google Scholar

3. Swanson JW, Tepper MC, Backlar P, et al: Psychiatric advance directives: an alternative to coercive treatment? Psychiatry 63:160–177, 2000Google Scholar

4. Winick B: Advance directive instruments for those with mental illness. University of Miami Law Review 51:57–95, 1996Google Scholar

5. Srebnik D: Benefits of psychiatric advance directives: can we realize their potential? Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice 4:71–82, 2004Google Scholar

6. Backlar P, McFarland B, Bentson H, et al: Consumer, provider, and informal caregiver opinions on psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 28:427–441, 2001Google Scholar

7. Geller J: The use of advance directives by persons with serious mental illness for psychiatric treatment. Psychiatric Quarterly 71:1–13, 2000Google Scholar

8. LaFond J, Srebnik D: The impact of mental health advance directives on patient perceptions of coercion in civil commitment and treatment decisions. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 25:537–555, 2002Google Scholar

9. Rosenson M, Kasten A: Another view of autonomy: arranging for consent in advance. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:1–7, 1991Google Scholar

10. Hardin S, Yusufaly Y: Difficult end-of-life treatment decisions: do other factors trump advance directives? Archives of Internal Medicine 164:1531–1533, 2004Google Scholar

11. Danis, M, Southerland L, Garrett J, et al: A prospective study of advance directives for life-sustaining care. New England Journal of Medicine 324:8820–8888, 1991Google Scholar

12. SUPPORT Principal Investigators: Do formal advance directives affect resuscitation decision and the use of resources for seriously ill patients? Journal of Clinical Ethics 5:23–30, 1994Google Scholar

13. Jordens C, Little M, Kerridge I, et al: From advance directives to advance care planning: current legal status, ethical rationales and a new research agenda. Internal Medicine Journal 35:563–566, 2005Google Scholar

14. Eisendrath S, Jonsen A: The living will: help or hindrance? JAMA 249:2054–2058, 1983Google Scholar

15. Howe E: Lessons from advance directives for PADs. Psychiatry 63:173–177, 2000Google Scholar

16. Atkinson J, Garner H, Harper G: Models of advance directives in mental health care: stakeholder views. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 39:667–672, 2004Google Scholar

17. National Resource Center on Psychiatric Advance Directives. Available at www.nrc-pad.orgGoogle Scholar

18. Srebnik DS, Russo J, Sage J, et al: Interest in psychiatric advance directives among high users of crisis services and hospitalization. Psychiatric Services 54:981–986, 2003Google Scholar

19. Endicott J, Spitzer R, Fleiss J, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766–771, 1976Google Scholar

20. Sherman P: Computer-assisted creation of psychiatric advance directives. Community Mental Health Journal 34:351–362, 1998Google Scholar

21. Peto T, Srebnik D, Zick E, et al: Support needed to create psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 31:401–409, 2004Google Scholar

22. Srebnik D, Rutherford L, Peto T, et al: The content and clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatric Services 56:592–598, 2005Google Scholar

23. Srebnik D, Uehara E, Smukler M, et al: The Problem Severity Summary: psychometric properties of a multidimensional assessment instrument for adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:1010–1017, 2002Google Scholar

24. Bigelow L, Berthot B: The Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 25:168–178, 1989Google Scholar

25. Overall J, Gorham D: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Google Scholar