Health-Related Quality of Life Among First-Degree Relatives of Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Italy

Obsessive-compulsive disorder has a major impact on the lives of patients and anyone who lives with them. Several self-report surveys found that the disease substantially interferes with patients' daily activities; disrupts family, social, and working life; and disturbs emotional well-being—all of which reduce quality of life ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). In recent years, health-related quality of life has been specifically investigated among individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder with tools such as the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), which allows comparisons with general population norms. The first study that examined health-related quality of life in this population suggested that patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder appear similar to persons in the U.S. general population in the domains of physical health but are impaired in the domains of mental health, including social functioning ( 4 ). Similar findings emerged from a Spanish study ( 5 ), which found that compared with persons in the general population, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder were more impaired in all domains except for physical functioning. Other authors, using the same instrument, confirmed the poorer health-related quality of life of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder in all domains except for physical functioning, as compared with community norms ( 6 , 7 ).

Moreover, quality of life among patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder is equally compromised ( 8 ) or even more compromised in some dimensions, such as psychological well-being and social relationships, than the quality of life among patients with other chronic psychiatric disturbances, such as schizophrenia ( 9 ).

All of these findings suggest that obsessive-compulsive disorder is a severe condition, with a high impact on patients' health-related quality of life. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, moreover, appears to impair family functioning in several ways. Families of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder are often more engaged in the illness than families of other psychiatric patients—that is, compulsions usually involve family members and the home itself ( 10 , 11 ). Van Noppen and colleagues ( 12 ) hypothesized that family members of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder move along a continuum that ranges from participating and assisting in the rituals to resisting and overtly opposing the rituals.

Accommodation is the term used to refer to the familial responses that are specifically related to obsessive-compulsive symptomatology: it includes behaviors such as feeling obliged to assist a relative with obsessive-compulsive disorder when he or she is performing a ritual or respecting the rules that obsessive-compulsive disorder imposes on the patient and, at the opposite side, interfering with the rituals or actively opposing them ( 10 ). Such accommodating behaviors have been investigated by using different methods. Shafran and colleagues ( 13 ) administered a questionnaire to 88 family members of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms: 60% of the family members were involved to some extent in rituals performed by the affected family member. Other researchers developed a specific instrument, the Family Accommodation Questionnaire (FAQ) ( 14 ), which assesses the nature and frequency of accommodating behaviors of family members of persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder. The investigators found a high degree of accommodation; moreover, accommodation of the family members was related to distress among patients and relatives. Another study from the same group, found that 88% of families accommodated the symptoms of 36 adult patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and that there was a correlation between high accommodation scores (as measured with the Family Accommodation Scale [FAS]), dysfunctional family interactions (as measured with the Patient Rejection Scale), and family distress and burden ( 15 ). In another study, 73 relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder were administered the FAQ and other rating scales measuring anxiety and depression; families that displayed a high degree of accommodation showed high levels of anxiety and depression ( 16 ).

Besides being directly involved in patients' symptoms, family members of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder frequently suffer from the consequences of living with and caring for people with a chronic and disabling disease ( 17 ). Various authors have defined this kind of nonspecific stress as family burden; it includes feelings of frustration, anger, and guilt, as well as loss of social activities. Magliano and colleagues ( 18 ) were the first to investigate the burden perceived by 32 key relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder compared with that perceived by 26 key relatives of patients with depression. Moderate to severe family burden was detected in both groups, with half to three-quarters of relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder experiencing poor social relationships, difficulty in taking holidays, and neglect of hobbies. Furthermore, relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder displayed depressive feelings more frequently than relatives of patients with depression.

Cooper ( 10 ) administered to 181 relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder a ten-item questionnaire that addressed the disturbances caused to family members by behaviors related to obsessive-compulsive disorder. The authors found that 82% of relatives displayed at least some disruption in personal and social life, whereas over 60% reported problems like marital discord, loss of leisure, and financial problems as a result of their relatives' disorder. Also, Black and colleagues ( 19 ) investigated the functioning of 15 spouses of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: 60% reported that caring for the relative with obsessive-compulsive disorder was burdensome, and nearly the two-thirds directly participated in the patients' rituals.

Although obsessive-compulsive disorder has been shown to exert a great influence on family functioning, health-related quality of life of relatives living with patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder has never been systematically investigated. The understanding of which relatives are more prone to experience a worsening in quality of life, moreover, could lead to the creation of specific strategies aimed at improving the family environment and consequently improving the family members' quality of life. Previous reports have shown that higher levels of family accommodation and caregiver burden predicted poorer family functioning and poorer response to treatment, including exposure and response prevention and pharmacotherapy. Moreover, reducing accommodation of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms or reducing caregivers' burden has proved useful in previous studies ( 20 , 21 ).

Therefore, the aim of the study presented here was, first, to examine health-related quality of life among relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and, second, to search for potential predictors of quality of life among these relatives.

Methods

Sample

We enrolled family members of patients with a principal diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The presence of obsessive-compulsive disorder was determined with a score of 16 or greater on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS). Patients were enrolled from the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Unit of the University of Turin, Italy. This is a tertiary referral center located within the university hospital and specialized in the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

All patients gave their informed consent before enrollment of a family member in the study. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the Regione Piemonte.

A systematic face-to-face interview that consisted of structured and semistructured components was used to collect data from patients. Diagnostic evaluation and axis I comorbidities were recorded with the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) ( 22 ).

For patients, all sociodemographic and illness characteristics were obtained through the administration of a semistructured interview, developed and used in previous studies ( 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ). Information was gathered in four areas. First, sociodemographic data were obtained—that is, age, sex, marital status (single, married, divorced, or widowed), and years of education. Second, information was gathered on the onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder—that is, disease onset was coded as the first month of occurrence of obsessive and compulsive symptoms, when at least one of the symptoms caused marked distress, was time-consuming (more than one hour a day), or interfered with the person's normal daily functioning (normal routine and occupational and social activities). Third, information was gathered on obsessive-compulsive symptomatology. For each patient up to three primary obsessions and compulsions were listed by using the symptom checklist found in the Y-BOCS ( 27 , 28 ). The Y-BOCS measures the severity of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Five items on the Y-BOCS inquire about obsessions and five items inquire about compulsions. Each of the ten items is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0, none, to 4, extreme. Total possible scores range from 0 to 40. Fourth, information was gathered on personality disorders. Personality status was assessed by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) ( 29 ).

In addition, the following rating scales were included in the assessment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) ( 30 ) and the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) ( 31 ). For both rating scales the total score is derived from summation of the items.

The interview and all the ratings were completed by psychiatrists with at least four years of experience in anxiety and mood disorders. High reliability and diagnostic concordance have been documented in previous reports ( 25 , 32 ).

For each patient, we selected one or more family members on the basis of the following criteria: family member was older than 18 years, was living with the patient for at least two years, did not have any history of mental disorder, was not involved in the care of any other family member with severe physical or mental illness, and gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Family members' general information was collected by means of informal interviews; then, in order to ensure the absence of any history of mental disorder, all potentially enrolled family members were directly interviewed with the SCID-I, Non-Patient version ( 33 ).

Accommodation for obsessive-compulsive disorder and health-related quality of life of family members who satisfied the above-mentioned inclusion criteria were then evaluated.

Family accommodation was measured by using a semistructured interview developed by Calvocoressi and colleagues ( 15 ), the FAS. Thirteen items were used. The first nine core items assessed two types of family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: participation in symptom-related behaviors (items 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) and modifications of functioning (items 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). The scores on these nine items are summed to yield a family accommodation score. Item 10 assesses relatives' distress when engaged in accommodating behaviors; items 11–13 assess the consequences of not accommodating the patient. Higher scores on items 1–5 indicate a greater involvement in obsessive-compulsive symptoms, higher scores on items 6–9 indicate a greater modification of functioning, and higher scores on items 10–13 indicate a greater personal distress and heavier consequences of not participating in patient's symptom-related behaviors.

Health-related quality of life was assessed by using the SF-36 ( 34 , 35 , 36 ). The SF-36 contains eight scales for assessing physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. For each scale, possible scores range from 0, worst possible health, to 100, best possible health. Summary scales include a physical composite and a mental composite that are expressed as t scores (mean±SD=50±10). The SF-36 has been validated for its use in Italian, and Italian norms are available for it ( 37 ).

Data analysis

One-sample t tests were used to compare scores on SF-36 subscales of the family members of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder with expected scores, which were based on 2,031 persons from the Italian general population (Italian norms) ( 37 ). We then examined the demographic and clinical correlates of quality of life first by comparing SF-36 scores with variables of the participants (sex, age, kinship, and FAS scores) and second by comparing SF-36 scores with variables of their relative with obsessive-compulsive disorder (sex, age, age at onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder, DSM-IV axis I and II comorbidity, Y-BOCS total score, scores on the obsession and compulsion subscales of Y-BOCS, and HAM-A and HAM-D scores). Comparisons were made by way of independent-samples t tests in the case of dichotomous variables and by way of Pearson product-moment correlations in the case of continuous variables.

Finally, the variables found to be significant at the conventional p level of .05 were entered into a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis with, as dependent variables, the physical and mental components of the SF-36.

Results

Seventy-seven family members were initially interviewed. All relatives who were approached to participate gave their consent, as did the patients they lived with. Seven family members had a history of mental disorder, three were caring for other severely ill relatives, and three had been living with their relative with obsessive-compulsive disorder for less than two years. These family members failed to meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded from the subsequent assessments, thus 64 family members participated in the study.

As shown in Table 1 , among the participants 26 (41%) were men, and the mean age was 49.9 years. Fifty-two percent were parents, 36% were spouses, 6% were offspring, and 6% were siblings. Table 1 also reports characteristics of the 48 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder whose family members participated into this study.

|

Mean SF-36 scores for family members of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder along with population-based means (Italian norms) are listed in Table 2 . Because our sample differed from the sample of the Italian population in gender ratio, we performed a different analysis considering males and females separately. Compared with the Italian population, relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder showed a greater impairment in health-related quality of life in the subscales of role limitations due to physical health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. These differences, except for role limitations due to physical health, remained significant when men and women were examined separately.

|

Although the mean age of our sample (49.9±12.8 years) did not differ from the mean age of the Italian population sample (47.73 years), we performed a one-sample t test comparing mean scores of participants in the age ranges 35–44 (N=11), 45–54 (N=17), and 55–64 (N=25) with the mean scores of the general Italian population for the corresponding age ranges (in the other age ranges there were too few persons). Although the statistical power was reduced, some differences between participants in our study and the Italian population remained statistically significant (vitality, social functioning, and mental health for those in the age range 45–54, and role limitations due to physical health for those in the age range 45–54, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health for those in the age range 55–64).

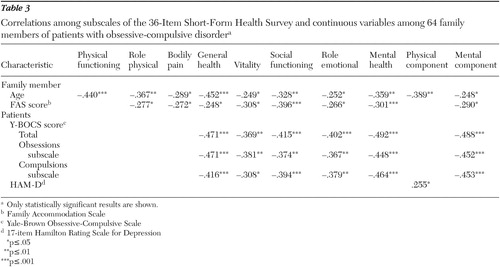

All significant correlations among continuous variables and one or more SF-36 subscales are shown in Table 3 . Concerning dichotomous variables, female family members scored significantly lower than male family members on subscales of the SF-36: physical functioning (80.00 versus 90.77; t=2.34, df=62, p=.023), bodily pain (59.13 versus 80.69; t=3.52, df=62, p=.001), vitality (45.92 versus 57.69; t=2.62, df=62, p=.011), and the global physical component (47.78 versus 53.13; t=2.22, df=62, p=.030). Moreover, being a parent was associated with a greater impairment in social functioning than being a spouse (55.30 versus 72.26; t=3.16, df=3, p=.040). When patients' variables were taken into account, relatives of patients with personality disorders had significantly lower scores in the domains of general health (57.08 versus 68.44; t=2.00, df=62, p=.050), role limitations due to emotional problems (46.14 versus 67.96; t=2.119, df=62, p=.038), and in the global mental component (35.93 versus 42.12; t=2.075, df=62, p=.042). Other patients' characteristics, such as gender, age, age at obsessive-compulsive disorder onset, axis I comorbidity (actual or lifetime), and HAM-A total score, did not predict their relatives' quality of life.

|

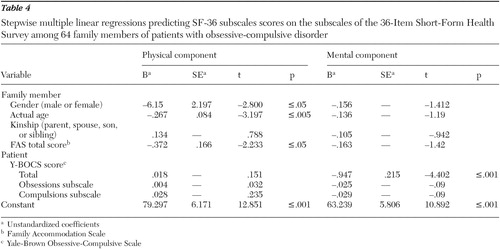

When a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was performed with the physical and mental components of the SF-36 as dependent variables, female gender, older age, and the FAS total score predicted a poorer score on the physical component, whereas the only predictor of a poorer score on the mental component was the Y-BOCS total score ( Table 4 ).

|

Discussion

This study was a first attempt to examine health-related quality of life among relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and to search for potential predictors of poorer quality of life by using a validated and highly used instrument, the SF-36.

Our data show that family members of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder are significantly more impaired in quality-of-life measures than the Italian general population. This is true especially in the mental health components of health-related quality of life measured by the SF-36. Scores from our study population on the SF-36 subscales—vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health—were significantly lower compared with scores from the Italian general population.

This result is in line with data from studies that indicate high distress and burden among families of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder ( 10 , 13 , 16 , 18 , 19 ). However, we are not aware of any other study that specifically investigated health-related quality of life among relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, so comparisons are not possible. Thus our study has to be viewed as a preliminary report and needs to be replicated in independent samples. Although we tried to rule out possible confounding factors (such as other family members with a chronic disorder) and we took into account gender and age-related differences between our sample and the Italian general population, there are still many other unmeasured factors that could account for the differences found.

We investigated health-related quality of life among relatives of severely ill patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (patients referred to a tertiary university center). Thus it is possible that our findings of poorer health-related quality of life among relatives (compared with community norms) are not applicable to persons whose relatives are not as severely ill. In our study, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder had a mean Y-BOCS total score of 26, high rates of at least another current or lifetime axis I disorder (52% and 73%, respectively), and high rates of at least one axis II disorder (63%). Future studies should expand our results to relatives of persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder alone (no other axis I or axis II disorder) and less severe obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Our analysis of predictors of health-related quality of life, however, helped us to draw a portrait of the relative who is more likely to suffer from the illness of his or her loved one. Relatives were more likely to reflect poorer quality of life in several domains if they were female or older, were parents (versus spouses), or had a tendency to accommodate the patient's obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Some characteristics of patients tended to lower their relatives' perceived quality of life: more severe obsessive-compulsive disorder and a co-occurring personality disorder were associated with lower scores of relatives in both the physical and mental components of quality of life. Nevertheless, when we put the variables into a stepwise multiple linear regression analysis, the Y-BOCS total score was the only variable that could significantly explain the variance in scores on the SF-36 mental component. It is relevant that neither HAM-A nor HAM-D scores significantly predicted worse health-related quality of life, nor did the presence of an axis I comorbid disorder (actual or lifetime). Thus it seems that severe obsessive-compulsive disorder symptomatology, and not generic anxiety or depressive symptoms, of the patient specifically impairs the mental functioning of the caregivers, making obsessive-compulsive disorder an illness at particularly high risk of causing mental distress among caregivers. It would be interesting to further compare relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder with relatives of those with major depression or panic disorder in order to confirm this specificity.

Regarding the physical component of health-related quality of life, only older age, female sex, and high accommodation attitudes of the relatives could significantly explain the variance in quality-of-life scores. Although female sex and older age are typically associated with lower SF-36 physical scores in the general population, high accommodation attitudes seem to impair the physical component more than the mental component of quality of life. One explanation might be that relatives feel righteous and helpful while assisting patients in their ritual but, at the same time, the physical effort is exhausting, which causes a poorer perceived physical quality of life among family members.

These results stress the need for family-oriented interventions when treating individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder, in order to improve the health-related quality of life of family members. Psychosocial programs or other interventions aimed at involving family members in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder could improve burden and perceived quality of life for caregivers, and such interventions should be implemented ( 20 ), although their effectiveness with this patient group would need to be demonstrated. Effectiveness has been demonstrated among caregivers of persons with other psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder ( 38 , 39 , 40 ).

Limitations of the study presented are the small sample of relatives, the cross-sectional evaluation of quality of life, and the severity of obsessive-compulsive disorder found in our sample—for example, our sample had high comorbidity rates for both axis I and II disorders. Our results should be interpreted cautiously and cannot be completely generalized to relatives of all patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our study provides evidence that obsessive-compulsive disorder impairs several dimensions of health-related quality of life among family members of persons with the disorder, even among healthy family members. Addressing family involvement and well-being of relatives and involving family members in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder could improve relatives' perceived quality of life and result in a better treatment outcome, although this has still to be demonstrated.

Factors that contribute more to a poorer quality of life of relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder are female gender, older age, being a parent (versus a partner), and a higher accommodation for and a higher severity of patient's obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Psychoeducational interventions could be specifically designed for relatives with these characteristics.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Stein DJ, Roberts M, Hollander E, et al: Quality of life and pharmaco-economic aspects of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a South African survey. South African Medical Journal 36(suppl 12):1579–1585, 1996Google Scholar

2. Hollander E, Stein DJ, Kwon JH, et al: Psychosocial function and economic costs of obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectrums 10:16–26, 1997Google Scholar

3. Sorensen CB, Kirkeby L, Thomsen PH: Quality of life with OCD: a self-reported survey among members of the Danish OCD Association. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 58:231–236, 2004Google Scholar

4. Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport L: Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:783–788, 1996Google Scholar

5. Bobes J, Gonzales MP, Bascaran MT, et al: Quality of life and disability in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. European Psychiatry 16:239–245, 2001Google Scholar

6. Moritz S, Rufrer M, Fricke S, et al: Quality of life in obsessive-compulsive disorder before and after treatment. Comprehensive Psychiatry 46:453–459, 2005Google Scholar

7. Eisen JL, Mancebo MA, Pinto A, et al: Impact of obsessive-compulsive disorder on quality of life. Comprehensive Psychiatry 47:270–275, 2006Google Scholar

8. Bystritsky A, Liberman RP, Hwang S, et al: Social functioning and quality of life comparisons between obsessive-compulsive and schizophrenic disorders. Depression and Anxiety 14:214–218, 2001Google Scholar

9. Stengler-Wenzke K, Kroll M, Matschinger H, et al: Subjective quality of life of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:662–668, 2006Google Scholar

10. Cooper M: Obsessive-compulsive disorder: effects on family members. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:296–304, 1996Google Scholar

11. Renshaw KD, Steketee G, Chambless DL: Involving family members in the treatment of OCD. Cognitive and Behaviour Therapy 34:164–175, 2005Google Scholar

12. Van Noppen B, Steketee G, McCorkle BH, et al: Group and multifamily behavioral treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a pilot study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 11:431–446, 1997Google Scholar

13. Shafran R, Ralph J, Tallis F: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms and the family. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 59:472–479, 1995Google Scholar

14. Calvocoressi L, Lewis B, Harris M, et al: Family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:441–443, 1995Google Scholar

15. Calvocoressi L, Mazure C, Kasl S, et al: Family accommodation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms: instrument development and assessment of family behavior. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:636–642, 1999Google Scholar

16. Amir N, Freshman M, Foa EB: Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 14:209–217, 2000Google Scholar

17. Steketee G: Disability and family burden in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:919–928, 1997Google Scholar

18. Magliano L, Tosini P, Guarneri M, et al: Burden on the families of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a pilot study. European Psychiatry 11:192–197, 1996Google Scholar

19. Black DW, Gafney G, Schlosser S, et al: The impact of obsessive-compulsive disorder on the family: preliminary findings. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186:440–442, 1998Google Scholar

20. Steketee G, Van Noppen B: Family approaches to treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 25:43–50, 2003Google Scholar

21. Renshaw KD, Steketee G, Chambless DL: Involving family members in the treatment of OCD. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 34:164–175, 2005Google Scholar

22. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition, version 2.0 (SCID-I/P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

23. Bogetto F, Venturello S, Albert U, et al: Gender-related clinical differences in obsessive compulsive patients. European Psychiatry 14:434–441, 1999Google Scholar

24. Albert U, Maina G, Ravizza L, et al: An exploratory study on obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without a familial component: are there any phenomenological differences? Psychopathology 35:8–16, 2002Google Scholar

25. Albert U, Maina G, Forner F, et al: DSM-IV obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: prevalence in patients with anxiety disorders and in healthy comparison subjects. Comprehensive Psychiatry 45:325–332, 2004Google Scholar

26. Maina G, Albert U, Salvi V, et al: Weight gain during long-term treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective comparison of serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:1365–1371, 2004Google Scholar

27. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al: The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: I. development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:1006–1011, 1989Google Scholar

28. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al: The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: II. validity. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:1012–1016, 1989Google Scholar

29. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1997Google Scholar

30. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology 32:50–55, 1959Google Scholar

31. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 23:56–62, 1960Google Scholar

32. Maina G, Albert U, Gandolfo S, et al: Personality disorders in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Journal of Personality Disorders 19:80–88, 2005Google Scholar

33. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 2001Google Scholar

34. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr: The MOS Short-Form General Health Survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care 26:724–735, 1988Google Scholar

35. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473–483, 1992Google Scholar

36. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al: SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1993Google Scholar

37. Apolone G, Mosconi P, Ware Jr JE: Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide [in Italian]. Milano, Guerini e Associati Editore, 1997Google Scholar

38. Reinares M, Vieta E, Colom F, et al: Impact of a psychoeducational family intervention on caregivers of stabilized bipolar patients. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 73:312–319, 2004Google Scholar

39. Bernhard B, Schaub A, Kummler P, et al: Impact of cognitive-psychoeducational interventions in bipolar patients and their relatives. European Psychiatry 21:81–86, 2006Google Scholar

40. Cuijpers P: The effects of family interventions on relatives' burden: a meta-analysis. Journal of Mental Health 8:275–285, 1999Google Scholar