Long-Term Employment Trajectories Among Participants With Severe Mental Illness in Supported Employment

Evidence suggests that most people with psychiatric disabilities who receive supported employment services, such as individual placement and support (IPS), can work in competitive employment ( 1 ). Supported employment provides assistance for interested job seekers in finding competitive jobs that are consistent with their skills, experiences, and preferences. Individualized support is provided as long as needed to maintain employment. There are currently 14 reported randomized controlled trials in different labor markets and economies, including Canada, Europe, Hong Kong, and the United States, documenting that supported employment is more effective than traditional stepwise vocational approaches that require people to participate in work readiness activities ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). These studies report employment outcomes for 12 to 24 months, showing that approximately 60% of the people in supported employment programs secure a competitive job. Most jobs are part-time and participants have a relatively brief job tenure of less than six months on average.

There have been few long-term follow-ups of supported employment participants. Test and colleagues ( 8 ) reported that work outcomes gradually improved over 12 years for 122 young adults with schizophrenia. Salyers and colleagues ( 9 ) followed up a small group (N=36) at ten years and found that most had worked, approximately one-third for at least five years, with a majority of current and recent jobs paying competitive wages. However, few had transitioned to full-time employment with health benefits.

A vast majority of literature in this area comes from studies limited to a two-year follow-up. Thus a critical question remains regarding the work careers of people with psychiatric disabilities beyond this short-term period: what is their pattern of work over many years? The purpose of the study presented here was to retrospectively discern individual work trajectories and generic work patterns over an eight- to 12-year period through a quantitative analysis. We further examined significant perceived influences given by participants concerning their work-related behavior through a qualitative analysis.

Methods

Setting

Two supported employment research studies were conducted at the same community mental health center in New England in the early to mid-1990s ( 10 , 11 ). The first study began in 1990 ( 10 ). Over an 18-month recruitment period, participants were randomly assigned to IPS within the mental health center or to a private rehabilitation agency for group skills training and employment support. They were followed for 18 months. The second study began in 1995 ( 11 ). This was a quasi-experimental study in which people who had attended day treatment services with sheltered employment for many years elected to receive IPS services. They were compared to a matched sample that did not receive IPS services. Because the agency has continued to offer IPS supported employment services for more than 15 years, the participants in both studies have had access to IPS services from the time of the original studies.

Participants

There were 48 IPS participants with complete vocational data in the first study ( 10 ) and 30 IPS participants in the second study ( 11 ). All long-term follow-up interviews for the study presented here (reinterviews) were conducted by the first author, between March 2004 and May 2004. Of the 48 people in the first study, 19 (40%) were reinterviewed, one had died, ten refused, 15 could not be located, two were hospitalized, and one was unable to give informed consent. Because the original follow-up interviews of the first study were conducted in 1992 and 1993, we will refer to this study as the 12-year follow-up group. Of the 30 people in the second study, 19 (63%) were reinterviewed for the study presented here, two had died, six refused, and three could not be located. Because the original follow-up interviews of the second study were held in 1996 and 1997, we will refer to this study as the eight-year follow-up group. Thus 38 people in total took part in the study presented here.

Procedures and measures

Participants in the two original studies who received IPS services were invited to participate in one follow-up reinterview in 2004. The study presented here was approved by the Dartmouth and New Hampshire institutional review boards, and all participants gave written informed consent.

We used a modified version of a semistructured interview developed for an earlier ten-year follow-up study ( 9 ). The interview includes information on demographic characteristics of the participants, information on Social Security and health insurance entitlements, employment history for the long-term follow-up period, work assistance provided during the long-term follow-up period, perceived facilitators of work, perceived barriers to competitive employment, and perceived effects of working.

Participants were asked to report on all work activities, including competitive employment, set-aside jobs with competitive wages, sheltered work, and volunteer work. Competitive employment is defined as community jobs that pay at least minimum wage (paid directly by the employer to the employee) that any person can apply for, including full-time and part-time jobs. Set-aside jobs with competitive wages are jobs that are reserved for people with disabilities and pay at least minimum wage.

Each participant's pattern of work was coded by the percentage of months worked in the long-term follow-up period: 1%–25% (1–24 months for the eight-year follow-up; 1–36 months for the 12-year follow-up), 26%–50% (25–48 months for the eight-year follow-up; 37–72 months for the 12-year follow-up), 51%–75% (49–72 months for the eight-year follow-up; 73–108 months for the 12-year follow-up), 76%–100% (73–96 months for the eight-year follow-up; 109–144 months for the 12-year follow-up). Recency of work was not included in the work pattern.

Most questions on the interview schedule were closed, but several open-ended questions were included in order to give participants an opportunity to describe matters relating to their work behaviors in their own words. The box on the previous page lists the open-ended questions. Responses to these questions formed the basis of the qualitative analysis. This analysis was propelled by the grounded theory approach outlined by Glaser and Strauss ( 12 ). This is an inductive method in which analysts do not approach data with a priori categories or hypotheses but instead develop a posteriori concepts and theory grounded in the experience, language, and categories most important to participants. The first and second authors independently examined the raw qualitative data with the aim of distilling frequently mentioned and meaningful themes raised by participants as perceived influences on their work behaviors. The authors then met to compare and contrast their individual efforts at thematic extraction. After discussion and further collaborative analysis, consensus was reached between the authors regarding important perceived influences on work-related behavior. This method adds rigor to qualitative analysis by acting as a check and balance on observer bias ( 13 ). The conceptual model grounded in the qualitative data is presented in the results.

Qualitative interview questions asked during the follow-up reinterview of 38 adults who participated in two supported employment studies

Work patterns

What were the reasons the job ended for you?

How did you get into this pattern of work?

How did you choose the type of work you've done?

How did you decide the number of hours that you worked in each job?

Work assistance

What problems have you had, if any, getting or finding a job?

What things have helped you find a job?

What kinds of problems have you had keeping jobs?

What kinds of things have helped you keep working after you got a job?

What advice would you give someone who wants to work?

Have there been any people who have helped you find or keep a job? Who? How were they helpful?

Perceived barriers to work

What was the main reason you were not working?

How did you overcome this problem to start working?

What is the main reason you are not working now?

Perceived effects of working

What are some of the positive aspects or benefits of working?

What are some of the negative aspects or drawbacks of working?

How have your work experiences changed how you see yourself?

What did you like most about the best job you had?

Results

Study group characteristics

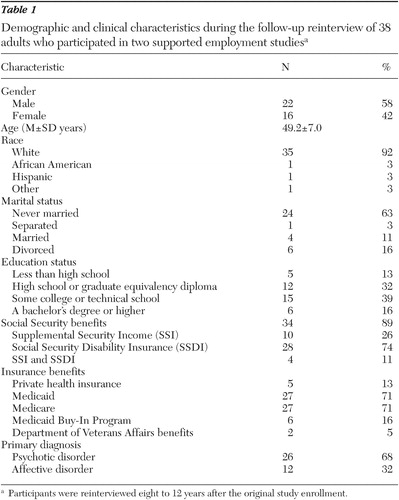

We first compared the participants from the eight-year follow-up and the 12-year follow-up and found no significant differences on diagnosis, gender, race, marital status, education, age, or competitive employment in the earlier study period. Because the groups were similar, we combined them for further analyses. Table 1 presents characteristics for the 38 participants in the total study group.

|

We compared the full sample of people reinterviewed and the sample of those who were not and found no significant differences in gender, marital status, education, competitive employment in the earlier study, and age. However, people who were reinterviewed were more likely to have a psychotic disorder than an affective disorder ( χ2 =6.33, df=1, p=.012).

Employment history

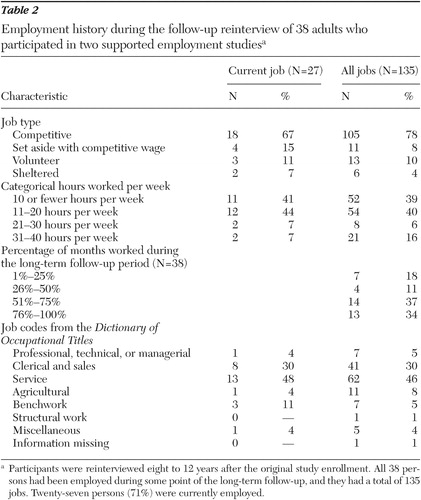

Table 2 presents information on all work during the long-term follow-up period. All participants worked at least one job. Most of the jobs (78%) were competitive, and most of the study group (31 participants, or 82%) worked competitively. Study group participants had a mean±SD of 3.39±2.20 competitive jobs and a mean of 3.55±2.13 jobs for all jobs—that is, competitive, set aside with competitive wage, volunteer, or sheltered. Study participants worked a mean±SD of 20±13 hours per week for the competitive jobs. The mean number of hours worked per week for any job was 17±12. Most people worked less than 20 hours per week, both in all jobs and in their current job. The mean total number of months worked on the longest competitive job was 4.6±3.3 years and the longest of any job was 4.8±3.0.

|

At the follow-up reinterview, 71% of the 38 participants were working. Of those people working, 67% held a competitive job, 15% held a job set aside for people with disabilities with competitive wages, 7% were in a sheltered work setting, and 11% held volunteer positions.

Twenty-seven (71%) study participants worked more than 50% of the long-term follow-up period. People who worked more than 50% of the long-term follow-up period (high-work group) were compared with those who did not (low-work group) on background characteristics, including diagnosis, race, marital status, gender, and age. There were no significant differences.

Consistent with the principle of individualized job match, participants worked in a variety of jobs. Most of the jobs were in service, clerical, and sales categories. A sample of job titles held by participants includes patient escort, bakery associate, recreation specialist, floral assistant, sales associate, postal clerk, security guard, and animal technician.

Employment services

At the time of the follow-up interview, 14 (37%) of the participants were receiving IPS supported employment services at the mental health center, four (11%) were receiving other employment services, and 20 (53%) were receiving no vocational services. Of the 14 people receiving IPS services, 11 (79%) were working, and of those working nine (82%) were competitively employed.

Social Security and health entitlements

A great majority of participants continued to receive benefits at long-term follow-up. Thirty-four (89%) were receiving Social Security benefits: ten (26%) received Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and 28 (74%) received Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). Twenty-seven (71%) received Medicaid, 27 (71%) received Medicare, and six (16%) reported participating in the Medicaid Buy-In Program. Twenty (53%) received both Medicare and Medicaid insurance.

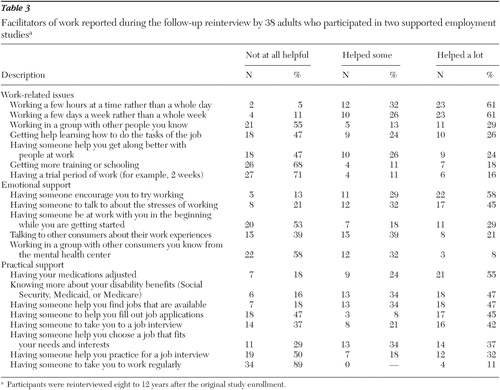

Facilitators of work

Participants reported that several kinds of supports facilitated their vocational careers, as shown in Table 3 . Working a few hours at a time rather than a whole day and working a few days a week rather than a whole week were most often rated as very helpful. Other highly rated factors were having someone to provide encouragement to try working, having medications adjusted, knowing more about disability benefits, and having someone to help find jobs.

|

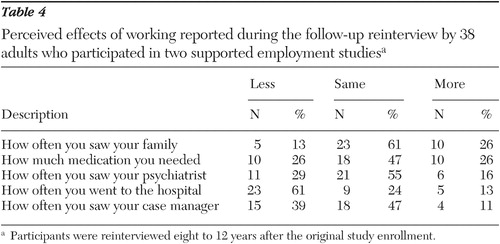

Perceived effects of working

Participants indicated that working did not affect the amount of contact that they had with practitioners and family or changes in medication ( Table 4 ). A large majority, however, reported that they went to the hospital less often when they were working.

|

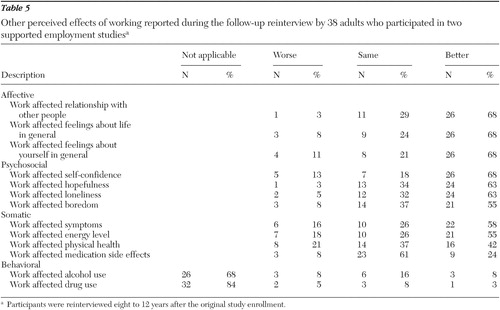

As shown in Table 5 , most participants reported that most other aspects of their lives were affected positively by working, such as relationships with other people, feelings about life in general, and feelings about themselves in general. Most people reported that work did not affect substance use, because most participants did not use alcohol or drugs.

|

Qualitative research findings

Three overlapping themes emerged from the qualitative analysis as significant perceived influences on participants' work-related behavior. The first theme regards the persistent and pervasive nature of participants' psychiatric problems. The successful management of symptoms and the deployment of appropriate coping skills appeared to play an important role in finding and maintaining work. Contrariwise, worsening symptoms often led to problems finding and maintaining work. This theme correlates with our quantitative finding regarding the importance of adjusting medications.

The second theme to emerge indicated that participants generally preferred to work part-time for two reasons. First, the lesser demands engendered by part-time work were more manageable in the light of the relative work inexperience and the pervasive nature of participants' mental illness. Second, part-time work was perceived to allow for the maintenance of Social Security and health care entitlements. Again this theme fits with our previous quantitative findings.

The final theme to emerge regarded the importance of ongoing IPS support. Participants stated that this was imperative in making successful transitions between jobs or from unemployment to employment. It also helped people within stable jobs, for example in helping negotiate pay raises or changes in conditions. The importance of IPS support correlates with our first theme, as well as with our quantitative results. The IPS workers were solid supports in times of instability, assisting participants through rough patches resulting from the cyclical nature of their mental illness.

In order to illuminate both our qualitative and quantitative findings, we describe Anthony, an individual whose work history and comments are given because they are typical of the wider data set. [Two additional descriptions of people who are representative and emblematic of the phenomenological experiences permeating the work behaviors of study participants are available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline. org.] (Note: pseudonyms are used and some key variables have been slightly altered to protect participants' anonymity.)

Anthony is a 50-year-old white non-Hispanic, single (never married) male with a bachelor's degree. He worked over 75% of the long-term follow-up period in eight jobs. He is currently working half-time in a position as an office assistant for a computer company, which he has held for four-and-a-half years. He explained that he has chosen to work in part-time jobs in order to develop the skills and confidence to work full-time. Support from family, friends, and IPS workers helped him to find jobs. Anthony said that mental illness was the major problem he faced before becoming employed. He said that symptoms from his mental illness made it difficult for him to perform work responsibilities. He uses coping skills (for example, listening to music and attending a self-help group) to help him stay employed. Although he reported accurate information about how work affects his entitlements, fear of losing benefits was not the reason he gave for working part-time. Anthony said, "[Work] establishes a routine, helps to maintain communication skills, and helps me feel more confident about myself. [Earning money] helps to pay the bills."

Discussion

This exploratory study reveals that the work trajectories for people with severe mental illness who have participated in supported employment are quite positive. All participants worked at least one job, with more than half working 50% or more of the eight- to 12-year follow-up period. Most were working at follow-up, and most were in competitive jobs.

In both the qualitative and quantitative findings, participants indicated that management of mental illness affected when they returned to work. Similarly, having medication adjusted facilitated their ability to work. They did not report that problems of concentration, memory, and other cognitive tasks affected their ability to work, as suggested by the literature ( 14 ). However, we did not ask about these issues. The lived experiences of people with psychiatric disabilities and how people with these disabilities refer to symptoms of mental illness may not have allowed participants to distinguish between cognitive, negative, and positive symptoms in the way that clinicians or researchers do.

Employment provided many positive benefits that reinforced the desire and ability to work. Similar to the earlier study that had a ten-year follow-up ( 9 ), people reported that it was helpful to work part-time, either by working a few days a week or a few hours a day. The qualitative data help to clarify that some people worked part-time to keep their entitlements.

A majority of people were receiving Social Security benefits at the time of the follow-up reinterview, and many indicated that they worked part-time in order to maintain benefits. A larger proportion of the study participants had SSDI in this study, compared with the proportion of those in the ten-year follow-up study by Salyers and colleagues ( 9 ) (74% versus 51%). SSDI is determined in part by work history, so it would be expected that there would be a higher employment rate in the study presented here. Are Social Security regulations functioning as a barrier for people with psychiatric disabilities to advance their work lives, or are they providing a useful safety net? Our data suggest the need for further examination of this issue.

During the long-term follow-up, a small proportion of people worked in set-aside jobs with competitive wages. These were mostly small consumer-run businesses located at a sheltered workshop operated by the community mental health center. Recently, the agency discontinued operating the workshop in favor of focusing on providing supported employment services.

The qualitative analysis indicated that people highly valued the support of the IPS workers. Less than half of the participants were receiving IPS services at the follow-up interview. This may indicate that people learned the skills of finding good job matches and developing effective coping mechanisms, becoming less reliant on IPS services over time.

Several limitations to this study warrant mention. These include a possible study selection bias for people with work experience who may have wanted to talk about their work success, the small study group of 38 participants, the low proportion of people with a co-occurring substance use disorder, the small city and New England location of the study, and a possible recall bias because of the extended period of follow-up. Finally, because the original comparison group was not reinterviewed, we do not know their work trajectories relative to the original experimental group that received supported employment services.

Conclusions

This exploratory study is in accord with the earlier follow-up by Salyers and colleagues ( 9 ) in suggesting positive long-term employment trajectories related to evidence-based supported employment. Participants not only worked substantially over years but they also reported numerous positive benefits related to work, ranging from illness management to self-esteem to social activity.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Ms. Becker and Dr. Drake have received funds from Johnson and Johnson. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313–322, 2001Google Scholar

2. Bond GR: Supported employment: evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:345–359, 2004Google Scholar

3. Bond GR: Critical ingredients of supported employment. Presented at a University of North Carolina-Duke University mental health seminar. Durham, NC, Duke University, Dec 14, 2004Google Scholar

4. Burns T, Catty J, Becker T: The effectiveness of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet, in pressGoogle Scholar

5. Latimer EA, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Generalizability of the Individual Placement and Support model of supported employment: results of the first non-US randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 189:65–73, 2006Google Scholar

6. Twamley EW, Narvaez JM, Becker DR, et al: Supported employment for middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, in pressGoogle Scholar

7. Wong KK, Chiu R, Tang B, et al: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Supported Employment Program on Vocational Outcomes of Individuals With Chronic Mental Illness. Hong Kong, Health Services Research Committee Dissemination Report, 2005Google Scholar

8. Test MA, Allness DJ, Knoedler WH: Impact of seven years of assertive community treatment. Presented at the American Psychiatric Association Institute on Psychiatric Services, Boston, Oct 6–10, 1995Google Scholar

9. Salyers MP, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Ten-year follow-up of a supported employment program. Psychiatric Services 55:302–308, 2004Google Scholar

10. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391–399, 1996Google Scholar

11. Bailey EL, Ricketts SK, Becker DR, et al: Do long-term day treatment clients benefit from supported employment? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:24–29, 1998Google Scholar

12. Glaser B, Strauss A: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York, Aldine, 1967Google Scholar

13. Strauss A, Corbin J: Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1990Google Scholar

14. McGurk SR, Mueser KT: Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: a review and heuristic model. Schizophrenia Research 70:147–173, 2004Google Scholar