Rural-Urban Differences in Hospitalization Rates of Primary Care Patients With Depression

Although national studies have reported that all-cause hospitalization rates are comparable for rural and urban populations ( 1 , 2 ), few investigators have examined whether hospitalization rates related to mental health are comparable for rural and urban populations. Research conducted in a single state demonstrated that individuals with depression in rural areas had greater odds of hospitalization for both physical and emotional problems over one year compared with urban individuals ( 3 ); however, these differences disappeared in models controlling for outpatient specialty mental health care during the month before hospitalization. These increased hospitalization rates do not appear to produce any clinical benefits, because rural and urban patients report identical outcomes over one year ( 4 , 5 ).

To test whether differential hospitalization rates could be observed over a broader geographical area, the research team analyzed an 11-state database to test whether rural primary care patients with depression would have greater odds of hospitalization for physical problems and for emotional problems over two years. Because previous research has found that differences between rural and urban hospitalization rates disappear in models that control for recent outpatient specialty care ( 3 ), we expected that any differential hospitalization rates we observed would be reduced in models controlling for outpatient specialty care in the previous six months. We tested these hypotheses by using longitudinal logistic regression models to examine whether rurality predicted hospitalization rates over two years, controlling for relevant patient characteristics.

Methods

Databases

We conducted a preplanned meta-analysis of two component studies in the Quality Improvement for Depression database ( 6 ): Partners in Care (PIC) ( 7 ) and Quality Enhancement by Strategic Teaming (QuEST) ( 8 ). Preplanned meta-analysis is the predefined analysis of shared measures in databases from two or more studies that employ comparable recruitment and data collection protocols ( 9 , 10 ).

Sample

PIC participants included a consecutively sampled cohort of 967 primary care patients with depression who were recruited from 46 practices in seven managed care organizations in five states, including three practices in Alamosa County, Colorado (1995 county population of 14,291), a nonadjacent non-metropolitan statistical area (MSA) located approximately 110 miles from the nearest MSA. The other 43 practices were located in MSAs.

QuEST participants included a consecutively sampled cohort of 479 primary care patients with depression who were recruited from 12 practices in 65 health plans in ten states, including four practices in non-MSA counties in Minnesota, North Dakota, Oregon, and Wisconsin. Within the non-MSAs, we recruited two practices in counties adjacent to a MSA and two practices in counties nonadjacent to a MSA. The four non-MSA practices were located in Fergus Falls, Minnesota, in Otter Tail County (1996 county population of 53,857), approximately 50 miles from the nearest MSA; Minot, North Dakota, in Ward County (1996 county population of 59,755), approximately 115 miles from the nearest MSA; Reedsport, Oregon, in Douglas County (1996 county population of 10,728), approximately 75 miles from the nearest MSA; and Mauston, Wisconsin, in Juneau County (1996 county population of 23,762), approximately 70 miles from the nearest MSA.

Both PIC and QuEST began enrolling participants in 1996. Patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were excluded from the study. QuEST excluded primary care patients who screened positive for alcohol dependence. PIC did not. For the PIC and QuEST projects, 35% (1,356 of 3,918) and 73% (479 of 653), respectively, of patients who screened positive for depression agreed to participate in the studies. Practices in both the PIC and QuEST studies were randomly assigned to intervention or control conditions. Intervention practices tested quality improvement initiatives to improve depression treatment in primary care. Because there were too few patients in the control group to test our hypotheses only in the control group, we controlled for intervention status as a potential confounder in all analyses where it predicted the dependent variable at p<.20. We chose not to weight participants for participation and attrition, because previous analyses weighting QuEST participants by the probability of participation and attrition produced virtually identical results to unweighted analyses ( 11 ). More detailed information on recruitment is available to interested readers in previous publications ( 7 , 8 ).

Data collection

QuEST administered all postscreener patient assessments of core constructs by telephone. PIC administered all postscreener patient assessments of core constructs by self-report mail survey, using telephone and in-person follow-up as needed. Patients in both studies were followed by using parallel protocols and instrumentation for five waves over two years, ending in 1999. Follow-up rates in PIC were 89% at six months, 87% at 12 months, 86% at 18 months, and 89% at 24 months. Follow-up rates in QuEST were 90% at six months, 82% at 12 months, 73% at 18 months, and 70% at 24 months. The studies were approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, the University of California at Los Angeles, and RAND.

Operational definition of major constructs

Rurality. Rurality was determined according to whether the practice location was in a MSA or a non-MSA. Patients recruited from MSA practices were classified as urban, whereas patients recruited from non-MSA practices were classified as rural.

Any hospitalization. Any hospitalization for physical problems was measured at baseline, six months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months by patient report of an overnight stay in a hospital or other treatment facility in the past six months for a physical problem. Any hospitalization for an emotional problem was measured by a parallel question at the same time points. We note that hospitalizations for physical problems in a depressed population are relevant because of recent discussion that depression may reduce a patient's ability to manage chronic medical conditions ( 12 ).

Any outpatient specialty care. Any outpatient specialty care was measured at baseline and at six, 12, 18, and 24 months by patient report of one or more visits in the past six months to a mental health professional—that is, a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker.

Covariates. Other potential contributors to probability of hospitalization include sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, treatment attitudes, insurance, and intervention status. Sociodemographic covariates were measured by patient report of baseline age, gender, minority status (member of a racial or ethnic minority group or not), education (high school educated or not), marital status (currently married or not), and employment status (employed full- or part-time or not). Clinical covariates were measured by patient report of depression severity, psychiatric comorbidity, physical comorbidity, antidepressant use, social support, and stressful life events, as described in a previous publication ( 6 ).

Depression severity was measured by the modified Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression, by using a scale with a range of 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater severity. Psychiatric comorbidity was measured by one or more panic attacks in the previous 12 months.

Physical comorbidity was measured by a checklist of chronic physical problems with a range of 1 to 14, with higher scores indicating greater physical comorbidity. Baseline antidepressant use was measured by use of antidepressant medication for two months or longer in the past six months.

Treatment attitudes were measured by patient report of the acceptability of antidepressant use, individual counseling, and group counseling scored as three dichotomous variables. Insurance status was measured by health insurer type and coded by a set of dummy variables (Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance versus no insurance). Intervention was measured by study records noting whether the patient was recruited from a practice that was randomly assigned to the intervention or control group.

Analysis

To compare baseline characteristics between rural patients and urban patients, we used two-tailed t tests for normally distributed continuous variables, Wilcoxon rank tests for nonnormally distributed continuous variables, and chi square tests for categorical variables. To test the hypothesis that rural primary care patients with depression have greater odds of hospitalization for physical problems and for emotional problems over two years, we employed longitudinal logistic regression models ( 13 ), in which the probability of any hospitalization over a six-month period was modeled with a logit link function and binomial distribution. Observations of each patient were assumed to be dependent by including subject random effects in the model. The final model included rurality and covariates that had p values less than or equal to .20 in univariate analysis ( 14 ). Generalized estimating equations ( 15 ) were used to obtain coefficients that we used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) for hospitalization for physical problems and the OR for hospitalization for emotional problems.

To test the hypothesis that rural-urban differences in the odds of hospitalization would disappear in models controlling for outpatient specialty care in the previous six months, we conducted mediation analysis ( 16 ), in which a series of models were fitted. The first mediation model tested whether rurality predicted outpatient specialty care visits, adjusting for other covariates. The second model tested whether outpatient specialty visits in the previous six months reduced rural-urban differences in hospitalization rates. The third model tested whether rural and urban patients with depression differed in the rate of outpatient specialty visits. Conservative power analyses indicated that the sample of 1,151 urban patients and 304 rural patients provided 80% power with p<.05 to find an OR of 1.8 or greater for hospitalizations for physical problems and an OR of 3.2 or greater for hospitalizations for emotional problems. All statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.1.

Results

Table 1 presents baseline sociodemographic, clinical, and utilization variables for the sample of 1,455 participants, subdivided into rural and urban populations. In the combined sample, 249 patients with depression (17%) were hospitalized at least once during the first year, with 222 (15%) hospitalized for physical problems and 60 (4%) hospitalized for emotional problems.

|

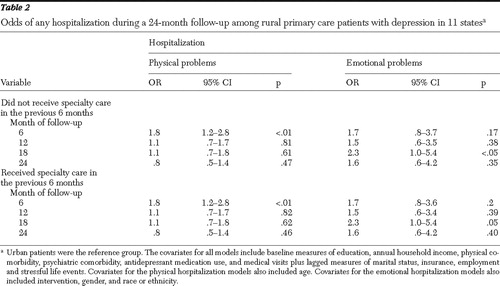

As shown in Table 2 , compared with urban patients with depression, their rural counterparts had significantly higher odds of being hospitalized for physical problems at six months (39 patients, or 13%, versus 79 patients, or 7%; OR=1.8, 95% CI=1.2–2.8, p<.01) and for emotional problems at 18 months (11 patients, or 4%, versus 16 patients, or 2%; OR=2.3, CI=1.0–5.4, p=.05). During the first year in the study, rural patients used outpatient specialty care (119 of 291 patients, or 41%; mean±SD=7.2±17.5 visits among users) at rates comparable to those of urban patients (429 of 1,053 patients, or 41%; mean±SD=5.4±12.9 visits among users). During the second year, rural patients used outpatient specialty care (92 of 274 patients, or 34%; mean±SD=5.8±16.7 visits among users) at rates comparable to those of urban patients (285 of 992 patients, or 29%; mean±SD=4.1±13.9 visits among users).

|

Rural-urban differences in hospitalization rates for physical and emotional problems remained in models that controlled for outpatient specialty care in the previous six months.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that compared with urban patients with depression, their rural counterparts reported statistically higher odds of hospitalization for physical problems at six months after study entry and for emotional problems at 18 months. These differential hospitalization rates were not explained by differences in outpatient specialty care in the previous six months, which were statistically comparable for rural patients and urban patients. Differences in hospitalization rates between rural residents and urban residents have not been observed in analyses of all-cause hospitalizations ( 1 , 2 ).

As in the single-state study ( 3 , 4 , 5 ), compared with their urban counterparts, rural primary care patients with depression had greater odds of any hospitalization for physical problems over a one-year period. In contrast to the single-state study, this study showed that greater odds of any hospitalization for emotional problems did not appear until the second year and that rural-urban differences in any hospitalization for physical or emotional problems did not disappear in models controlling for specialty outpatient care before hospitalization. The differences between previous and current findings might be explained by different practice patterns in a single state, compared with multiple states, or by the different impact of outpatient specialty care provided when a patient is at immediate risk of hospitalization (as in the single-state study) compared with six months before hospitalization (as in the study presented here).

These findings have policy relevance for the redesign of the delivery system for rural mental health services. Although the field is far from being able to estimate optimal hospitalization rates for depressed populations, it is likely that a nontrivial proportion of these rural hospitalizations are preventable ( 17 , 18 ). "Excess" hospitalization of depressed rural populations may have dropped in the past decade. The OR of 3.0 in the single-state study dropped in the study presented here to 2.3 for hospitalization for emotional problems and 1.8 for hospitalization for physical problems. However, insurers may still be paying more money to achieve comparable outcomes among rural patients with depression. Second, because we could find no evidence that receipt of specialty care outpatient services reduces the odds of greater hospitalization in rural populations, insurers may wish to explore providing integrated depression care management to reduce potentially unnecessary hospitalizations initiated by the primary care provider.

However, before insurers of rural populations can expect integrated depression care management models to reduce "excess" hospitalization, the field needs to identify the modifiable factors that explain the differential hospitalization rates we observed. It seems reasonable to assume that patient and system factors work at different stages in the course of illness to influence hospitalization for physical and emotional problems. For example, rural-urban differences in hospitalization for physical problems peaked at six months after study entry and then receded, suggesting that rural clinicians attribute diminished functioning of patients with depression to worsening physical disease when they did not recognize depression at the beginning of an episode. Rural-urban differences in hospitalization for emotional problems peaked at 18 months before receding, suggesting that rural clinicians may have hospitalized patients with depression when patients worsened with the available treatment.

The internal validity of our results is strengthened by the utilization of common protocols for the measurement of key constructs in comparable patient populations; however, the study also has limitations that we acknowledge. First, health services research studies conducted across multiple delivery systems have to rely on patient report to measure utilization to avoid systematic bias introduced by differing error rates across different health plans ( 19 , 20 , 21 ). Previous research by our group and others indicates that self-reported utilization introduces random rather than systematic measurement error in rural-urban or intrarural comparisons ( 22 , 23 , 24 ). Second, we note that patient rurality can be categorized only by the primary care practice's rurality at baseline, introducing the possibility that we may have inaccurately categorized a few rural residents who we recruited from urban primary care clinics.

The external validity of our findings is strengthened by this study's extension of service substitution patterns in a single state to those patterns in multiple states. The 17% annual hospitalization rate that we observed for primary care patients with depression is considerably greater than the 12% annual hospitalization rate for all American adults in 2002 ( 25 ). Policy analysts expect patients with depression to have higher rates of hospitalization, concordant with the higher health care utilization of patients with depression ( 26 ). Although participants represented a population-based sample of primary care patients with depression in each participating practice, we note that readers should not generalize our results to the nation because both studies recruited a voluntary sample of patients from primary care practices. However, to our best knowledge this database is and will remain for the foreseeable future the largest multiple-state longitudinal database available to examine rural-urban differences in hospitalization rates in a diagnostically confirmed population of patients with depression.

Conclusions

These findings contribute to the literature synthesis ( 27 ) by demonstrating that rural patients with depression were hospitalized more often for physical and emotional problems than their urban counterparts. Future studies are needed to determine the generalizability of our findings across geographic areas and time. These studies should seek to identify modifiable patient and systems factors that lead to higher frequency of hospitalization for rural patients. The identification of these factors will allow researchers to design and test interventions that simultaneously improve the quality and cost of depression care in rural areas.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grant 1-U1-CRH03713-01-00 from the Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and grants MH-54444, and MH-63651 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Partners in Care was supported by grant R01-HS-08349 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and grants R10-MH-57992 and P50-MH-54623 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors acknowledge the principal investigator of Partners in Care, as well as the investigators, staff, participating clinicians and patients for their support and the practice organizations and associated behavioral health organizations for their participation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Himes CL, Rutrough TS: Differences in the use of health services by metropolitan and nonmetropolitan elderly. Journal of Rural Health 10:80–88, 1994Google Scholar

2. Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Fillenbaum G, et al: Health services access and use among older adults in North Carolina: urban versus rural residents. American Journal of Public Health 85:1384–1390, 1995Google Scholar

3. Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, et al: Rural-urban differences in depression treatment and suicidality. Medical Care 36:1098–1107, 1998Google Scholar

4. Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, et al: Persistently poor outcomes of undetected major depression in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry 20:12–20, 1998Google Scholar

5. Rost K, Fortney J, Zhang M, et al: Treatment of depression in rural Arkansas: policy implications for improving care. Journal of Rural Health 15:308–315, 1999Google Scholar

6. Rost K, Duan N, Rubenstein LV, et al: The Quality Improvement for Depression collaboration: general analytic strategies for a coordinated study of quality improvement in depression care. General Hospital Psychiatry 23:239–253, 2001Google Scholar

7. Wells KB: The design of Partners in Care: evaluating the cost-effectiveness of improving care for depression in primary care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:20–29, 1999Google Scholar

8. Rost KM, Nutting PA, Smith J, et al: Designing and implementing a primary care intervention trial to improve the quality and outcomes of care for major depression. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:66–77, 2000Google Scholar

9. Olkin I: Meta-analysis: reconciling the results of independent studies. Statistics in Medicine 14:457–472, 1995Google Scholar

10. Rubin DM: A new perspective, in The Future of Meta-Analysis. Edited by Watcher KW, Straf ML. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1990Google Scholar

11. Rost KM., Smith JL, Dickinson M: The effect of improving primary care depression management on employee absenteeism and productivity: a randomized trial. Medical Care 42:1202–1210, 2004Google Scholar

12. Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al: Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biological Psychiatry 58:175–189, 2005Google Scholar

13. Cox DR, Snell EJ: Analysis of Binary Data, 2nd ed. London, Chapman and Hall, 1989Google Scholar

14. Blough DK, Madden CW, Hombrook MC: Modeling risk using generalized linear models. Journal of Health Economics 18:153–171, 1999Google Scholar

15. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73:13–22, 1986Google Scholar

16. Baron RM, Kenny DA: The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51:1173–1182, 1986Google Scholar

17. Himelhoch S, Weller WE, Wu AW, et al: Chronic medical illness, depression, and use of acute medical services among Medicare beneficiaries Medical Care 42:512–521, 2004Google Scholar

18. Niefeld MR, Braunstein JB, Wu AW, et al: Preventable hospitalization among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:1344–1349, 2003Google Scholar

19. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan C, et al: Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:2836–2845, 2002Google Scholar

20. Roy-Byrne P, Craske M, Stein MB, et al: A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication for primary care panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:290–298, 2005Google Scholar

21. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

22. Yaffe R, Shapiro S: Medical economics survey-methods study: cost effectiveness of alternative survey strategies, in Health Survey Research Methods Third Biennial Conference. Edited by Sudman S. DHHS pub no 81-3268. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1981Google Scholar

23. Yaffe R, Shapiro S, Fuchsberg RR, et al: Medical economics survey-methods study: cost-effectiveness of alternative survey strategies. Medical Care 16:641–659, 1978Google Scholar

24. Golding JM, Gongla P, Brownell A: Feasibility of validating survey self-reports of mental health service use. American Journal of Community Psychology 16:39–51, 1988Google Scholar

25. The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at www.ahrq.gov/data/hcupGoogle Scholar

26. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:850–856, 1995Google Scholar

27. Rost KM, Fortney J, Fischer E, et al: Use, quality, and outcomes of care for mental health: the rural perspective. Medical Care Research and Review 59:231–265, 2002Google Scholar