Best Practices: The Development of the Social Cognition and Interaction Training Program for Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

Impairments in social functioning are among the hallmark characteristics of schizophrenia. A majority of outpatients report having few, if any, close friends, and they rate social functioning as their area of greatest unmet need ( 1 ). Thus focusing on social impairments may address a basic need among individuals with schizophrenia, which may impact long-term recovery.

Given the importance of social dysfunction in schizophrenia, an important clinical goal has been to elucidate best practices for improving social functioning. This interest has led to recent enthusiasm for the role of social cognition in schizophrenia as a potential treatment target ( 2 ), especially given its association with functional outcomes ( 3 ). Social cognition is a domain of cognition that has been defined as the "mental operations underlying social interactions, which include the human ability and capacity to perceive the intentions and dispositions of others" ( 4 ).

In this column, we describe the development of a new treatment, the Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT) program, which is a group-based intervention that is delivered weekly over a six-month period, with the purpose of improving both social cognition and social functioning for individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The development of SCIT as a potential best practice for rehabilitating persons with schizophrenia followed a stage-model approach, which views manual and treatment development as comprising three phases: conceptualization, standardization, and pilot testing ( 5 , 6 ).

Treatment conceptualization

Development of SCIT was informed by both literature reviews ( 2 , 3 ) and basic research from our laboratory, which has been involved in research on social cognition in schizophrenia for the past 15 years. Social cognition in schizophrenia is conceptualized as being composed of three broad domains: emotion perception (that is, the ability to identify the affect expressed by others), attributional style (that is, the causal explanations given for positive and negative outcomes), and theory of mind (that is, the ability to understand others' intentions or perspectives).

We have learned that individuals with schizophrenia are impaired in emotion perception, even when performance on non-social perception tasks is accounted for. Furthermore, they do not utilize context during social information processing, which may be the result of looking at less essential aspects of social stimuli. Individuals with persecutory delusions are unique in terms of their attributional biases, because they blame others rather than situations for negative outcomes, which is known as a "personalizing bias." This personalizing bias may be a result of difficulties in theory of mind, cognitive rigidity, and a tendency to jump to conclusions, which reflects an intolerance of ambiguity.

The next step was to examine whether other treatment programs addressed social cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Extant social cognitive interventions can be classified as either targeted or broad based ( 3 ). Targeted interventions focus on a specific social cognitive domain (for example, theory of mind), whereas broad-based interventions combine a variety of psychosocial approaches, including cognitive remediation, social skills training, and social cognition training. Although both approaches improve social cognition, several key issues remain unaddressed. First, can we expect the narrow focus of targeted interventions to yield improvements across social cognitive domains or to generalize to social functioning? Second, if targeted interventions are too narrow, are broad-based interventions too burdensome? That is, is it necessary to stack social cognitive training atop intensive cognitive remediation and social skills training, or might social cognitive training alone be sufficient to improve social functioning?

To address these issues, we developed a comprehensive, stand-alone intervention that targeted emotion perception, theory of mind, and attributional style, as well as the processes underlying them (for example, cognitive rigidity, jumping to conclusions, and intolerance of ambiguity).

Treatment standardization

The development of SCIT was based on guidelines from the stage model of psychotherapy development ( 5 ), with the goal of creating a manual that had the following elements: overview and rationale of SCIT; a description of the phases of SCIT; elements of treatment that are essential, recommended, and proscribed; session format and structure; content and goals; and clinical vignettes. We used seed funds to hire university actors to portray various social cognitive difficulties (for example, jumping to conclusions). These portrayals were used in a DVD or VHS supplement that could be implemented throughout the SCIT protocol.

SCIT is composed of three phases: emotion training, figuring out situations, and integration. Training is delivered by one or two therapists over 24 weekly sessions, with each session lasting 50 minutes. During emotion training, our goals are to provide information about emotions and their relationship to thoughts and situations, define the basic emotions, improve emotion perception via commercially available computer-based programs, and teach clients to distinguish between justified and unjustified suspiciousness.

Our primary goals during figuring out situations are to teach clients about the potential pitfalls of jumping to conclusions, improve cognitive flexibility in social situations, and help clients distinguish between personal and situational attributions and between social "facts" and social "guesses." We use a variety of supporting materials and activities to achieve these goals. For example, we ask clients to independently generate facts based on photographs of people interacting (for example, "there are two women in this picture") and to compare this list to a second, independently generated list of guesses about what is happening or what the relationship is between the people. This exercise typically shows excellent agreement among clients regarding facts but more variability regarding guesses, with the lesson being that it is best to draw conclusions from facts rather than guesses. We also play a variation of the game 20 questions, whereby clients are encouraged to ask more questions (and are penalized for making early guesses), so as to improve tolerance of ambiguity and thereby reduce the tendency to jump to conclusions.

The purpose of the final phase, integration, is to put into practice what clients have learned in SCIT. During this phase, clients are encouraged to bring up troubling interpersonal situations, and then they are walked through the process of identifying the other person's affect, distinguishing facts from guesses, avoiding jumping to conclusions, and coming up with a solution or action plan. For example, a client might believe that his roommate had been angry with him. In collaboration with the group, the client would discuss the roommate's facial features and how they corresponded to the emotions that had been discussed. Then the client is prompted to distinguish facts (for example, the roommate said that he was too busy to talk to him) from guesses (for example, the roommate couldn't talk to him because he was angry) and then generate possible solutions, which could be to do nothing, to get more information (for example, ask a friend of the roommate about his mood), or to "check it out" (for example, ask the roommate if something is wrong). For the latter solution, the client would participate in a series of role plays with the therapist or other clients, so as to strengthen his social skills in this situation.

Pilot testing

Pilot testing, a requisite step in establishing SCIT as a best practice, is composed of two stages: open clinical trials to evaluate feasibility and clinical benefits and a randomized controlled trial to evaluate whether uncontrolled clinical findings are due to the intervention or to extraneous factors. SCIT is still in stage one of pilot testing. Therefore, the results should be interpreted very cautiously.

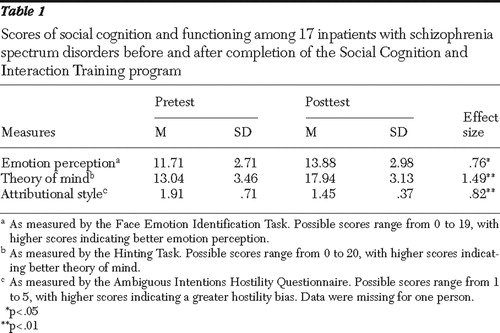

Over a two-year period two groups of inpatients have completed the SCIT program: seven individuals at Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina ( 7 ), and ten individuals at the Oklahoma Forensic Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who were the first cohort from a larger treatment study ( 8 ). A majority of the individuals had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (12 clients, or 71%), were male (12 clients, or 71%), and were Caucasian (13 clients, or 76%). Because of the small samples, we have combined the results from these two samples (N=17) in Table 1 , although these preliminary results, reflecting two different samples, should be interpreted carefully. Results showed that SCIT was associated with improved emotion perception (as measured by the Face Emotion Identification Task) ( 9 ), improved theory of mind (as measured by the Hinting Task) ( 10 ), and a reduced tendency to attribute hostile intent to others (as measured by the Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire) ( 11 ), with effect sizes being in the medium-large range.

|

Discussion

An important component of manual development is to include clients and clinicians early in the process, because this can promote treatment dissemination and acceptance ( 12 ). Therefore, after treatment, we administered a short questionnaire to clients asking them to indicate how much they agreed with the following statements: the materials were understandable, the program was useful, the program helps you to think about social situations, and the program helps you to relate to other people. Nearly all clients (16 of 17 clients, or 94%) indicated that they agreed or strongly agreed with these statements, suggesting that SCIT was well tolerated by participants.

We have recently implemented SCIT in an outpatient setting in collaboration with two agencies in New York: the Federation Employment and Guidance Services and the Bridge. This gave us an opportunity to obtain feedback from clinicians who were not affiliated with our research group. Three outpatient groups were led by five clinicians, who were asked to indicate how much they agreed with the following statements: the manual was helpful, the program improved the clients' social cognition, and the program improved clients' social interactions. The feedback was very positive, as all five responding clinicians either agreed or strongly agreed with all the statements.

Conclusions

SCIT has shown promise in improving social cognition for inpatients with psychotic disorders and appears to be well tolerated by clinicians and clients. Although randomized controlled trials have not been performed yet and replication across different settings and laboratories is still needed, our initial findings indicate that SCIT has promise as a best-practices candidate. We hope that the processes delineated in this column—conceptualization, standardization, and pilot testing—are the initial steps in that direction.

1. Middelboe T, Mackeprang T, Hansson L, et al: The Nordic study on schizophrenic patients living in the community: subjective needs and perceived help. European Psychiatry 16:207–214, 2001Google Scholar

2. Penn DL, Addington J, Pinkham A: Social cognitive impairments, in American Psychiatric Association Textbook of Schizophrenia. Edited by Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, Perkins DO. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2006Google Scholar

3. Couture S, Penn DL, Roberts DL: The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32(suppl 1):S44–S63, 2006Google Scholar

4. Brothers L: The social brain: a project for integrating primate behavior and neurophysiology in a new domain. Concepts in Neuroscience 1:27–61, 1990Google Scholar

5. Carroll KM, Nuro KF: One size cannot fit all: a stage model of psychotherapy manual development. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 9:396–406, 2002Google Scholar

6. From Intervention Development to Services: Exploratory Research Grants (R34). National Institute of Mental Health. Available at www.nimh.nih.gov/researchfunding/grantawardr34.cfmGoogle Scholar

7. Penn DL, Roberts D, Munt ED, et al: A pilot study of social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 80:357–359, 2005Google Scholar

8. Combs DR, Adams SD, Penn DL, et al: Social cognition and interaction training: preliminary findings from an inpatient sample. Schizophrenia Research, in pressGoogle Scholar

9. Combs DR, Penn DL, Wicher M, et al: The Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire (AIHQ): a new measure for evaluating hostile social cognitive biases in paranoia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry 12:128–143, 2007Google Scholar

10. Corcoran R: Theory of mind and schizophrenia, in Social Cognition and Schizophrenia. Edited by Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2001Google Scholar

11. Kerr SL, Neale JM: Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? Journal of Abnormal Psychology 102:312–318, 1993Google Scholar

12. Westen D: Manualizing manual development. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 9:416–418, 2002Google Scholar