Demographic and Clinical Profiles of Patients Who Make Multiple Visits to Psychiatric Emergency Services

Several studies have shown that a relatively small number of patients account for a disproportionate number of visits to psychiatric emergency services ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). However, attempts to describe clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of these patients have yet to produce consistent profiles.

The prevalence of multiple-visit patients in the psychiatric emergency service population has been reported to range from 5% to 56% ( 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ). A consistent finding is that as a group they are more chronically socially impaired than single-visit patients ( 1 , 2 , 4 , 6 , 8 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ). However, correlations of chronic impairment with a particular diagnosis have not been forthcoming because many studies report heterogeneous profiles for this group ( 2 , 4 , 5 , 8 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ). In studies in which a predominant diagnosis could be ascertained for multiple-visit patients, schizophrenia appears to be the most common ( 1 , 3 , 6 , 7 , 10 , 19 , 20 ), although personality and anxiety disorders have also been reported ( 21 , 22 ).

The structure of delivery of psychiatric health care in Montreal, Canada, makes the psychiatric emergency service a useful tool for the long-term study of multiple-visit patients. Each service is assigned a geographic sector, and citizens within it are obliged to seek acute psychiatric care at that service only ( 23 ). Data from 1996 to 2000 indicate that 57% of citizens of metropolitan Montreal remained at the same address over the five-year period. Many patients who changed residences moved to locations where they were still subject to the rules of their original sector ( 24 ). Government-run universal health care precludes the direct billing of patients for a medical service. Its fee structure significantly favors hospital-based practice, and acute care private-practice alternatives are poorly developed. Payments are independent of diagnosis, which prevents third-party reimbursement policies from influencing clinicians' diagnostic decisions, such as is sometimes the case for substance use diagnoses in the United States ( 6 ).

The aim of this study was twofold. We attempted to better define the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients who made multiple visits to a psychiatric emergency service in a major hospital in downtown Montreal. Second, we assessed whether the diagnostic information we obtained for the patient groups could be generalized to other, functionally dissimilar psychiatric emergency services.

Methods

Data collection

Clinical and demographic data were obtained from all adult patients visiting site A, the psychiatric emergency service of a major university teaching hospital, from June 15, 1985, to December 31, 2000. The geographic sector increased in size between 1997 and 1999, which increased the number of citizens served—from 90,000 to 180,000. Approximately 4.8% of all patients who underwent triage in the medical emergency department were referred for a psychiatric assessment. Specialized nursing and psychiatric staff covered the service on weekdays. Evenings and weekends were covered by regular staff psychiatrists or psychiatric residents, who were required to be available in the hospital for their on-call duties.

The database, originally an "in-house" register kept by the nursing staff, was begun on June 15, 1985, with seven variables: name, sex, service sector, referral source, date and time of entry into the psychiatric emergency service, date and time of departure, and patient disposition. This information was obtained each time a patient visited the psychiatric emergency service. A variable for age was added in January 1990. In the six months beginning January 1996 a series of small studies assessing the feasibility of gradually increasing the number of variables collected (to 20) were initiated.

On July 1, 1996, the data collected since 1985 were entered into a PC-based relational database ( 25 ), and the database was expanded as a research project to include 62 additional clinical and demographic variables per visit. The main database table contained administrative variables, such as the chart number, name, sex, and so forth). Linked tables contained variables pertinent to the consultation process, such as date and time of arrival, reasons for the referral, DSM-IV diagnoses (three per visit, either obtained directly from staff after the patient was interviewed in the emergency service or from the patient's chart), disposition, and so forth. Data entry was performed by designated members of the nursing staff and by the principal investigator. If neither was present, charts were held in the emergency department until they could be reviewed for all pertinent information. For patients with two or more visits, diagnostic profiles were produced by attributing a "most probable" primary diagnosis. This was the diagnosis most frequently given; the second most frequently given diagnosis was retained as the comorbid diagnosis.

As noted, the study also aimed to determine whether the diagnostic profiles obtained at the main study site were generalizable to other psychiatric emergency services. Data for the variables in the database described above were collected for a two-year period (September 2002 through August 2004) for patients visiting the main study site—site A—and three functionally dissimilar emergency services—sites B, C, and D. Sites C and D were in Canadian cities other than Montreal. Patients at site B were not medically triaged before being referred to the emergency service, and site C, unlike the other sites, did not have an observation area. All variables in the database were listed in a paper format, which was used as the primary psychiatric triage instrument for all patients visiting the four services during the two-year period ( 26 ). The completed forms were forwarded to the principal investigator on a weekly basis for data entry.

To minimize diagnostic uncertainty in both data collection efforts, only services that were covered by experienced daytime psychiatric staff were included and diagnoses were grouped into broad categories. Because of sector regulations, multiple-visit patients at sites A, B, and C were usually familiar to staff, who attempted to refer them to outpatient services. For 245 of the 292 patients with the highest number of visits at the main study site, diagnostic uncertainty could be clarified by discussions with the treating team.

Primary data analysis

Data were analyzed by using the statistical analysis program Systat (version 11). Analyses of nominal variables were performed with the "crosstabs" section for one- and two-way tables after their transformations into percentage tables. Independence of cell frequencies was assessed by the Pearson chi square statistic. Odds ratios were used as a measure of association in 2×2 tables.

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) scientific subcommittees at sites A, C, and D and was exempted from full review. Full IRB approval was required at site B.

Results

In the 15.5-year (1985–2000) data collection period, 14,825 patients made 29,569 visits. A total of 10,571 patients (71%) made single visits, whereas 4,254 patients (29%) made more than one visit. Of the latter group, 2,046 (14% of all patients) made two visits (4,092 visits), 1,916 (13%) made from three to ten visits (8,826 visits), and 292 patients (2%) made 11 or more visits (6,080 visits, or 21% of all visits).

A small number of patients were found in each of the three multiple-visit groups who had visits across the 15.5 years spanned by the database. More typically, however, the longer the observation period, the more patients with 11 or more visits were noted. For example, if the database had ended at month 30—much shorter than 15.5 years but longer than the observation periods used in previous studies—the proportions of patients making two, three to ten, and 11 or more visits would have been 77%, 47%, and 8%, respectively.

Time to the second visit poorly discriminated between multiple-visit groups, because the second visit took place within six months of the first visit for 50% to 60% of the multiple-visit patients. For patients who made two visits, the mean±SD number of days to the completion of the second visit was 612±938 (median=183 days). For patients who made three to ten visits, the mean number of days to the completion of all visits was 1,423±1,308 (median=1,004). For patients who made 11 or more visits, the mean number of days to the completion of all visits was 3,245±1,487 (median=3,350).

Possible differences between the four groups—the single-visit and the three multiple-visit groups—in time of arrival at the service were assessed for 24-hour periods and for individual weekdays. The mean number of visits for each consecutive four-hour period within a day (beginning at midnight) was determined. Over the 15.5 years, approximately 64% of all visits (N=18,924 visits) occurred between 8:00 a.m. and 7:59 p.m. No significant differences were observed between the four groups. No between-group differences were found in day-of-week patterns of use. Visits (N=29,569) were about equally distributed over the five weekdays (from 14.7% to 15.9% of all visits). Approximately 12% of visits were made on Saturdays and 11.5% on Sundays.

Table 1 shows the age-group distributions for the four user groups. When age-group proportions in the Montreal population 20 years and older were used for comparison, persons from the younger age groups (age 44 and younger) were overrepresented in the emergency service, especially in the group that made 11 or more visits. Although this overrepresentation was more predominant for men, the difference was not significant. Sex distribution was similar in the four groups. Women accounted for 51% (N=149) of the group with 11 or more visits, 47% (N=4,968) of the single-visit group, 47% (N=901) of users with three to ten visits, and 45% (N=923) of the two-visit group.

|

We then assessed whether the four user groups differed on any clinical or epidemiological variables. Information for these variables was almost exclusively obtained from July 1, 1996, to December 31, 2000. Eight broad diagnostic categories were examined: adjustment disorders, personality disorders, affective disorders, schizophrenia, anxiety and somatoform disorders, substance abuse or dependence, psychosis not otherwise specified, and organic mental disorders. Forty-one percent of all the single-visit patients had a primary diagnosis in one of the eight categories. The corresponding numbers for the multiple-visit patients reflected the fact that they had a greater probability of having at least one visit at which a diagnosis could be made within the above time period. The values were 57% (1,160 of 2046 patients) for the two-visit patients, 70% (1,333 of 1,916 patients) for the patients with three to ten visits, and 90% (264 of 292 patients) for the patients with 11 or more visits.

As Table 2 shows, patients with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia accounted for 47% of the group with 11 or more visits. Odds ratios indicated that patients in this high-frequency user group were significantly more likely to have schizophrenia than to have a diagnosis in any of the other broad diagnostic categories (p<.001); odds ratios ranged from 2 (for schizophrenia compared with personality disorders) to 29 (for schizophrenia compared with psychosis not otherwise specified).

|

Patients with more visits were more likely to have a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis. Among the 4,331 single-visit patients where a primary diagnosis could be ascertained, 1,342 (31%) had a comorbid diagnosis. For the two-visit patients 476 of 1,160 patients (41%) had a comorbid diagnosis, for those with three to ten visits 693 of 1,333 (52%) had a comorbid diagnosis, and for those with 11 or more visits 161 of 264 (61%) had a comorbid diagnosis. Odds ratios assessing the probability of having a comorbid diagnosis and being in the group with 11 or more visits were significant and ranged from a low of 1.4 (for the comparison between the highest-use group and the group with three to ten visits; p<.05) to 5.2 (for the comparison between the highest-use group and the single-visit group; p<.001). The rate of comorbid personality disorders was similar and ranged from 25% to 27% across the three multiple-visit groups, as was the rate of adjustment disorders (9% to 12%) and the rate of anxiety disorders (5% to 7%).

Among the 161 patients with 11 or more visits who had a comorbid disorder, 9% (N=15) had a comorbid organic mental disorder, compared with only 2% (N=10) of the 476 patients with two visits who had comorbid disorders and the 3% (N=21) of the 693 patients with three to ten visits who had comorbid disorders. Comorbidity of an affective disorder was also more frequent among the patients with 11 or more visits (17%, or 27 patients) than among those with two visits (13%, or 64 patients) or those with three to ten visits (13%, or 94 patients). The more visits patients had the less likely they were to have a comorbid diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence; among the 1,342 single-visit patients with a primary diagnosis, 39% (N=523) had a substance use disorder; the rate was 20% (N=32) among the 161 patients with 11 or more visits.

Comorbid diagnoses were assessed among patients with schizophrenia because they were overrepresented in the group with 11 or more visits. Patients with schizophrenia who had more visits also had higher rates of comorbid diagnoses. Of 464 patients with schizophrenia who made single visits, 16% (N=72) had a comorbid diagnosis. The rates were 25% for two-visit patients with schizophrenia (52 of 204 patients), 42% for patients with three to ten visits (158 of 378 patients), and 52% for patients with 11 or more visits (64 of 123 patients). Odds ratios assessing the probability of having schizophrenia plus a comorbid diagnosis and being in the high-frequency user group ranged from 1.5 (for the comparison between the highest-frequency group and those with three to ten visits; p<.05) to 5.9 (for the comparison between the highest-frequency group and the single-visit group; p<.001).

Because of the small number of patients, a more detailed analysis of comorbid diagnoses was not conducted for patients with schizophrenia. However, 44% (32 of 72) of the patients with schizophrenia in the single-visit group who had a comorbid disorder had comorbid substance abuse or dependence, whereas the rate was 26% (17 of 64) for those with schizophrenia in the group with 11 or more visits. Among the 64 patients with schizophrenia who had 11 or more visits, 17 (26%) had a comorbid affective disorder and 17 (26%) had a comorbid personality disorder. Among patients with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia who had a comorbid disorder, neither affective disorders nor personality disorders attained a greater than 15% proportion of comorbid diagnoses among the 72 patients in the single-visit group, the 52 patients who made two visits, or the 158 patients with three to ten visits.

In the database 26 possible reasons for a referral to the psychiatric emergency service were listed, and one reason was given for each of the 12,704 visits that occurred in the 4.5-year period. Ten of the 26 reasons accounted for 11,180 (88%) of these visits. The ten reasons were mania (508 visits), drug or alcohol intoxication (584 visits), anxiety (597 visits), psychosis (775 visits), delusional ideation (800 visits), behavior disorder (915 visits), suicide attempt (1,220 visits), relapsed schizophrenia (1,283 visits), suicidal ideation (1,956 visits), and depression (2,542 visits). The pattern for each user group generally reflected its diagnostic profile. Four reasons were cited at least 50% less frequently for patients in the highest-frequency group than for those in the single-visit group: anxiety, depression, drug or alcohol intoxication, and suicide attempt. Three reasons were cited at least 50% more frequently for patients in the highest-frequency group than for patients in the single-visit group: schizophrenia, conduct disorder, or mania. The other reasons were independent of group.

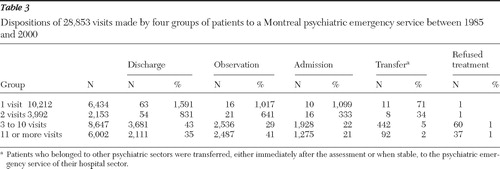

As Table 3 shows, patient disposition differed substantially between groups. As expected from the diagnostic profile of the group with 11 or more visits, these patients were more frequently placed under observation or hospitalized than those in the other groups.

|

Financial security was assessed with several variables, and the degree of financial insecurity was related to the diagnostic profiles. Over the 4.5-year period, information about social assistance was obtained at the index visit of 2,073 single-visit patients, 545 two-visit patients, 675 patients with three to ten visits, and 176 patients with 11 or more visits. Rates of receiving welfare were 35% (N=726) for single-visit patients, 48% (N=262) for two-visit patients, 64% (N=432) for patients with three to ten visits, and 82% (N=144) for patients with 11 or more visits. Odds ratios assessing the probability of receiving welfare and being in the highest-frequency group ranged from 2.8 (for the comparison between the highest-frequency group and the group with three to ten visits; p<.001) to 8.8 (for the comparison between the highest-frequency group and the single-visit group; p<.001). Only 6% (N=11) of the patients in the highest-frequency group were employed at their index visit, compared with 40% (N=1,859) of the single-visit patients. Patients in the single-visit group were 9.8 and 3.7 times more likely to be employed than patients in the highest-frequency group and patients in the two-visit group, respectively (p<.001). Only slight differences separated the four user groups in terms of social variables (for example, percentage living alone and marital status), which rendered statistical comparisons of doubtful significance.

We next assessed whether the diagnostic profiles of patients could be generalized. As described above, data for the same variables were acquired at the main study site and in three dissimilar psychiatric emergency services for a two-year period beginning September 2002. Because of the short duration of this data collection period, a group equivalent to the highest-frequency users of site A was difficult to ascertain, although the 475 patients who made five or more visits at all four sites were the closest match; the 475 patients accounted for 3.5% of 13,577 patients seen at the four sites and 17% (N=3,571) of the 21,004 visits made during the two years at all four sites. The aggregate results for all four sites showed that the diagnostic profiles of the single-visit group and the highest-frequency group were quite similar to the profiles of these groups at the main study site for the earlier data collection period. Although variations were observed for individual sites, schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis in the highest-frequency group —overall and at three of the four sites ( Table 4 ).

|

Discussion

Our results are consistent with those of previous studies ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 ) in that a minority of patients accounted for a majority of psychiatric emergency service visits and thus represented a substantial burden to this service. The disproportionately high use of emergency services by a relatively small number of patients has also been reported in medical emergency departments of hospitals in cities throughout the world and under a variety of private and public health care delivery systems ( 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ). Managed care, either locally administered ( 32 ) or universally administered as in the study reported here and in other studies ( 4 , 22 , 33 ), does not appear to confer a substantial advantage in preventing this phenomenon.

The importance of heavy use of psychiatric emergency services by a small number of patients has been shown to vary widely from one psychiatric emergency service to another, suggesting that methodological issues may contribute to this variability ( 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ). In the study reported here strict sector regulations combined with a long data acquisition period permitted us to fully appreciate the extent to which a few patients can account for a large proportion of visits. Only a fraction of the patients in our study who had 11 or more visits completed them within 30 months. Most previous studies have had a timeline of 12 months or less, and some have used retrospective chart reviews ( 2 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 10 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 34 , 35 ). Few studies categorized patients in terms of the frequency of visits ( 3 , 6 , 10 , 21 , 22 , 34 ), a technique found to be useful in this study in identifying diagnostic profiles. Pooling diagnoses of patients with two or more visits and using a short observation period ( 2 , 4 , 7 , 8 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 19 , 35 ) would tend to shift the diagnostic profile of multiple-visit patients closer to that of single users, which would partly account for the difficulty in obtaining reproducible results. In the study reported here the conservative methodology used to generate the diagnostic profiles (primary and comorbid) represents its major limitation. Some diagnoses, especially comorbid diagnoses, may have been underrepresented, which may have been exacerbated in the single-visit group and the two-visit group because patients in these groups were assessed less often.

Our results suggest that the diagnostic profile of patients visiting a psychiatric emergency service shifts toward a more chronic and severe psychopathology as the number of visits increases and the psychosocial profile shifts toward greater instability. Among patients who made 11 or more visits, the number of men and women was about equal. Compared with patients in the other user groups, those with 11 or more visits were more likely to be diagnosed as having schizophrenia, were more likely to have a comorbid diagnosis, and were generally younger at the index visit and more economically impaired. This finding could be partly generalized to psychiatric emergency services at three other sites. Overall, and at two of the three other sites, schizophrenia was overrepresented in the highest-frequency user group (patients making five or more visits); one of the other sites included a service to which patients were referred without prior medical triage.

Among patients who made single visits, 3% had a personality disorder, compared with 14% of patients who made three to ten visits. The rate did not increase significantly in the group with 11 or more visits. This finding was somewhat unexpected. Nevertheless, it is in keeping with reports suggesting that the severity of certain personality disorders may subside over a five-year period ( 36 , 37 ). The proportion of patients with a personality disorder leveled off among patients with three to ten visits, and the mean time to completion of ten visits in this user group was about four years. Therefore, personality disorders contributed more to the overall and site-specific profiles of multiple-visit patients in the two-year data collection period (2002–2004). A previous report that used a five-year timeline and that categorized patients in terms of the frequency of visits to the emergency service found that patients with schizophrenia accounted for a large portion of the high-use group and that the proportion of patients with schizophrenia increased in each higher-use group ( 6 ). In addition, diagnostic profiles similar to those in the study reported here were found among patients making low and intermediate numbers of psychiatric emergency service visits. Patients in the higher-use groups were also more likely to have a comorbid affective disorder and a precarious socioeconomic standing ( 6 ). No data were reported for substance abuse and dependence, however, which represents that study's major limitation.

In another long-term psychiatric emergency service study in which patients were given a diagnosis of comorbid substance abuse or dependence if it were evident at any one visit, the diagnosis was more prevalent in the groups with more visits ( 3 ). Using much more conservative criteria, we found substance abuse and dependence to be an important primary and comorbid diagnosis for all multiple-visit patients, although proportionally less so among patients with 11 or more visits. Because we used five or more visits as a criterion for high-frequency use in the multicenter analysis, the identified group most likely included patients who would have been classified as frequent users (three to ten visits) at our main study site. Therefore, substance abuse and dependence contributed more to the diagnostic profile in the multicenter analysis, both overall and at two of the sites. Patients with a primary or comorbid diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence and patients with chronic mental illnesses in general account for a significant proportion of multiple visits to the medical emergency department ( 38 , 38 , 40 , 41 ) and thus represent a significant overall burden on both psychiatric and medical emergency services.

The time of the visit to the emergency service did not differ between the four user groups. Most visits occurred during daytime hours on weekdays, which suggests the possibility of diverting some high-frequency users to outpatient or community-based mental health services. However, it appears that this option would have been unlikely to reduce high-frequency use of the emergency service in our study because most of these patients (245 of 292) were already under multidisciplinary case management. Psychosocial and substance abuse problems have also been shown to render high-frequency users of the medical emergency department poor candidates for transfer to a general practice setting ( 28 ).

Conclusions

The predominance of schizophrenia among high-frequency users of psychiatric emergency services and the shifts in diagnostic profiles related to visit frequency are our primary and secondary findings. Both might prove useful in helping shape the future development of these services. Integrating specialized hospital-based teams for detecting first-episode psychosis and treating severe and persistent psychosis could help reduce the number of multiple visits made by the highest users. Community-oriented strategies, such as modified intensive case management and outreach programs—which have been shown to reduce the heavy use of psychiatric inpatient services ( 42 )—could also help limit high-user visits by reducing social instability and increasing treatment compliance.

Hospital-based and community-based resources abound for patients with visits at the intermediate frequency levels; such resources include outpatient clinics for personality disorders and government-subsidized detoxification centers. Continued research in this setting can help ensure that psychiatric emergency services become increasingly specialized in their role as a first-line interface between the community and the hospital setting.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was partly supported by grant 2200-089 from Valorisation Recherche Québec. The authors thank the following site-specific principal investigators: Lucie Beaulieu, M.D., Edith Labonté, M.D., and Michel Paradis, M.D.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Surles RC, McGurrin MC: Increased use of psychiatric emergency services by young chronic mentally ill patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:401–405, 1987Google Scholar

2. Klinkenberg WD, Calsyn RJ: The moderating effects of race on return visits to the psychiatric emergency room. Psychiatric Services 48:942–945, 1997Google Scholar

3. Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, et al: Emergency department use of persons with co-morbid psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Annals of Emergency Medicine 41:659–667, 2003Google Scholar

4. Oyewumi LK, Odejide O, Kazarian SS: Psychiatric emergency services in a Canadian city: I. prevalence and patterns of use. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 37:91–95, 1992Google Scholar

5. Ellison JM, Blum NR, Barsky AJ: Frequent repeaters in a psychiatric emergency service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:958–960, 1989Google Scholar

6. Sullivan PF, Bulik CM, Forman SD, et al: Characteristics of repeat users of a psychiatric emergency service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:376–380, 1993Google Scholar

7. Dhossche DM, Ghani SO: A study on recidivism in the psychiatric emergency room. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 10:59–67, 1998Google Scholar

8. Munves PI, Trimboli F, North AJ: A study of repeat visits to a psychiatric emergency room. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:634–638, 1983Google Scholar

9. Vasiamatzis G, Kontaxakis V, Markidis M, et al: Social and resource factors related to the utilization of emergency psychiatric services in the Athens area. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 75:95–98, 1987Google Scholar

10. Nurius PS: Emergency psychiatric services: a study of changing utilization patterns and issues. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 13:239–254, 1984Google Scholar

11. Stebbins LA, Hardman GL: A survey of psychiatric consultations at a suburban emergency room. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:234–242, 1993Google Scholar

12. Slaby AE, Perry PL: Use and abuse of psychiatric emergency services. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 10:1–9, 1981Google Scholar

13. Arfken C, Zeman LL, Yeager L, et al: Frequent visitors to psychiatric emergency services: staff attitudes and temporal patterns. Journal of Behavioural Health Services and Research 2:490–496, 2002Google Scholar

14. Kent S, Yellowlees P: The relationship between social factors and frequent use of psychiatric services. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 29:403–408, 1995Google Scholar

15. Bauer SF, Balter L: Emergency psychiatry patients in a municipal hospital: demographic, clinical and dispositional characteristics. Psychiatric Quarterly 45:382–393, 1971Google Scholar

16. Lim HI: A psychiatric emergency clinic: a study of attendances over six months. British Journal of Psychiatry 143:460–466, 1983Google Scholar

17. Bassuk E, Gerson S: Chronic crisis patients: a discrete clinical group. American Journal of Psychiatry 137:1513–1517, 1980Google Scholar

18. Spooren DJ, De Bacquer D, Van Heeringen K, et al: Repeated psychiatric referral to Belgian emergency departments: a survival analysis of the time interval between the first and second episodes. European Journal of Emergency Medicine (England) 4:61–67, 1997Google Scholar

19. Santos ME, do Amor JA, Del-Ben CM, et al: Psychiatric emergency service in a university general hospital: a prospective study [in Portuguese]. Revue Saude Publica 34:468–474, 2000Google Scholar

20. Hansen TE, Elliott KD: Frequent psychiatric visitors to a Veterans Affairs medical center emergency care unit. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:372–375, 1993Google Scholar

21. Adityanjee, Mohan AD, Wig NN: Unwelcome guests: bugbears of the emergency room physician. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 34:196–199, 1988Google Scholar

22. Pasic J, Russo J, Roy-Byrne P: High utilizers of psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatric Services 56:678–688, 2005Google Scholar

23. Beland F, Lemay A, Lavoie G: Psychiatric emergencies in the context of community mental health services. Santé Mentale Quebec 18:227–250, 1993Google Scholar

24. Community Profiles, Montréal, Québec (census metropolitan area), Mobility Status—place of residence 5 years ago. Montreal, Statistics Canada. Available at www.statscan.ca. Accessed Dec 10, 2005Google Scholar

25. Moreau J, Couture M, Lacroix D, et al: Information technology in the psychiatric emergency service [in French]. Revue Française de Psychiatrie et de Psychologie Médicale. 35:81–83, 2000Google Scholar

26. Lebel, MJ, Chaput Y: The future development of the psychiatric emergency service based upon clinical and epidemiological data [in French]. Info Urgence 20:24–27, 2006Google Scholar

27. Andren KG, Rosenqvist U: Heavy users of an emergency department: psycho-social and medical characteristics, other health care contacts and the effect of a hospital social worker intervention. Social Science and Medicine 21:761–770, 1985Google Scholar

28. Dent AW, Phillips GA, Chenhall AJ, et al: The heaviest repeat users of an inner city emergency department are not general practice patients. Emergency Medicine (Fremantle) 15:322–329, 2003Google Scholar

29. Blank FS, Li H, Henneman PL, et al: A descriptive study of heavy emergency department users at an academic emergency department reveals heavy ED users have better access to care than average users. Journal of Emergency Nursing 31:139–144, 2005Google Scholar

30. Bond TK, Sterns S, Peters M: Analysis of chronic emergency department use. Nursing Economics 17:207–213, 1999Google Scholar

31. Byrne M, Murphy AW, Plunkett PK, et al: Frequent attenders to an emergency department: a study of primary health care use, medical profile, and psychosocial characteristics. Annals of Emergency Medicine 41:309–318, 2003Google Scholar

32. Claassen CA, Kahsner MT, Gilfillan SK, et al: Psychiatric emergency service use after implementation of managed care in a public mental health system. Psychiatric Services 56:691–698, 2005Google Scholar

33. Perez EL, Minoletti A, Blouin A, et al: Determinants of hospitalization of psychiatric emergencies in a Canadian General Hospital. American Journal of Social Psychiatry 1:54–59, 1985Google Scholar

34. Schwartz DA, Weiss AT, Miner JM: Community psychiatry and emergency service. American Journal of Psychiatry 129:710–715, 1972Google Scholar

35. Santos M, Bascunana Morejon de Giron J, Lumbreras GG, et al: Evaluation of the functional component underlying the frequent attendance to a hospital emergency service and its economic consequences [in Portuguese]. Anales de Medicina Interna 17:410–415, 2000Google Scholar

36. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg RR, Hennen J, et al: The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 160: 274–283, 2003Google Scholar

37. Paris J: Recent advances in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:435–441, 2005Google Scholar

38. Huang JA, Tsai WC, Chen YC, et al: Factors associated with frequent use of emergency services in a medical center. Journal of the Formosa Medical Association 102: 222–228, 2003Google Scholar

39. Mandelberg JH, Khun RE, Kohn MA: Epidemiologic analysis of an urban, public emergency department's frequent users. Academic Emergency Medicine 7:637–646, 2000Google Scholar

40. Kennedy D, Ardagh M: Frequent attenders at Christchurch Hospital's Emergency Department: a 4-year study of attendance patterns. New Zealand Medical Journal 117:871, 2004Google Scholar

41. Kne T, Young R, Spillane L: Frequent ED users: patterns of use over time. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 16:646–652, 1998Google Scholar

42. Quinlivan R, Hough R, Crowell A, et al: Service utilization and costs of care for severely mentally ill clients in an intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services 46:365–371, 1995Google Scholar