Economic Grand Rounds: Coverage and Prior Authorization of Psychotropic Drugs Under Medicare Part D

The Medicare Modernization, Improvement, and Prescription Drug Act (MMA) of 2003 created Medicare Part D, a voluntary prescription drug benefit available to all Medicare beneficiaries. The MMA also shifted drug coverage from the Medicaid program to Part D for the more than six million individuals dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, requiring that "dual eligibles" enroll in a private prescription drug plan (PDP). Dual eligibles were randomly assigned to PDPs with monthly premiums at or below regional premium benchmarks (below benchmark). Part D relies on private plans to administer the benefit and offers beneficiaries a variety of plan options with different formulary coverage, cost sharing, and use of utilization management tools, such as prior authorization.

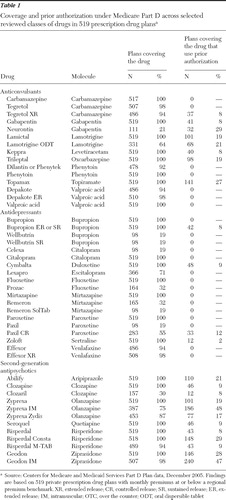

Although the MMA requires plans to cover a minimum of two drugs in each therapeutic class, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) extended special protections to three common psychotropic drug classes: antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants. For these three "protected" classes, plans must cover "all or substantially all" molecules (distinct drugs), but they are not required to cover both the generic and brand versions of the same molecule (for example, they must cover fluoxetine or Prozac but not necessarily both) or all formulations of a molecule (for example, they must cover Effexor or Effexor XR but not necessarily both). However, Part D enrollees can appeal for coverage of a particular medication that is not covered by their plan. In addition, plans can use a variety of utilization management tools, such as prior authorization, for all psychotropic drugs.

There was some concern that PDP formulary coverage and prior authorization would restrict use of psychotropic medications despite the special protections granted and that such restrictions could negatively impact patients with mental illness, particularly dual eligibles, who are disproportionately more likely to have a mental illness. Prior authorization, used widely in state Medicaid programs to contain prescription drug costs, has been shown to shift the market share away from drugs requiring prior authorization and to reduce the overall use of medications in affected drug classes ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). However, because psychotropic medications were excluded from most Medicaid prior authorization programs until recently, the effect of prior authorization on psychotropic medication use is poorly understood. Because psychotherapeutic drugs may be less therapeutically interchangeable for some patients than drugs in certain other categories, the effects of coverage restrictions and prior authorization may be particularly problematic for psychotropic medications ( 4 ).

We investigated these concerns by examining coverage and use of prior authorization among covered drugs for commonly used medications in the three protected classes among the below-benchmark stand-alone PDPs to which dual eligibles may be autoenrolled (an individual is automatically assigned to a PDP, so coverage will not lapse). Dual eligibles pay a fixed copayment for all generic drugs (either $1 or $2, depending on their income) and a higher fixed copayment for all brand drugs (either $3 or $5, depending on their income). Because these copayment levels are similar to what dual eligibles faced under Medicaid and because dual eligibles pay a single rate for all brand drugs, regardless of whether the brands are preferred by the plan or not, we focused our analysis on coverage and prior authorization rather than on tiering and cost-sharing levels.

We obtained data from CMS for all PDPs as of December 2005, reflecting coverage at the inception of Part D. Our unit of observation was the PDP at the regional level, so PDPs offering a plan across multiple regions were counted once for each region. By using this definition, there were 1,429 PDPs serving the United States as of December 2005, and 519 of these were below-benchmark plans to which dual eligibles could be autoenrolled. We focused on coverage and prior authorization among below-benchmark plans only. If any dosage of a given drug was covered, we considered that drug to be covered. Similarly, if prior authorization was required for any dosage form of a covered drug, we considered that drug to require prior authorization. Some plans also used stepped therapy or quantity limits to control drug utilization, but we were unable to study use of these tools with our data source.

Findings

Formulary coverage

As shown in Table 1 , below-benchmark plans generally covered at least one formulation of all molecules in the three classes. The exception is that a number of plans covered either Celexa or Lexapro but not both; because these drugs are isomers of the same molecule, CMS requires that only one be covered. Coverage can be more limited for certain product formulations or for the brand version of a drug with a generic equivalent available. For example, 100% of plans covered the generic paroxetine, whereas only 19% covered the brand Paxil and 55% covered the controlled-release form, Paxil CR.

|

Use of prior authorization

Although a majority of plans did not require prior authorization for covered drugs in the three classes, a sizeable minority of plans required it for specific medications. Use of prior authorization varied considerably across drugs within a class. For example, among second-generation antipsychotics, use of prior authorization for plans that covered the drug ranged from 8% (Clozaril) to 48% (Zyprexa IM). Use of prior authorization was more common for covered second-generation antipsychotics and anticonvulsants than for antidepressants.

Conclusions

The special protections afforded to antidepressant, antipsychotic, and anticonvulsant medications under the Part D benefit will help to ensure that Medicare beneficiaries with a mental illness have access to needed medications. However, despite these protections, certain product formulations may not be covered and prior authorization may be used by a minority of plans. Although dually eligible beneficiaries are permitted to change plans at any time (unlike beneficiaries without dual eligibility, who may switch plans only once a year), dual eligibles with a mental illness may have greater difficulty assessing plan options and switching plans than beneficiaries without a mental illness. The effect on beneficiaries will depend on the restrictiveness of both the prior authorization and appeals processes, which is unknown at this point. Importantly, plans' formulary coverage and use of management tools, such as prior authorization, are likely to change over time as experience with the program increases. Ongoing monitoring of these issues is important to ensure that beneficiaries have access to needed medications.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by grant K01-MH-66109 (Dr. Huskamp) from the National Institute of Mental Health, by the Roadmap Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Development Award grant K12-RR-023267 (Dr. Donohue) from the National Institutes of Health, by grant P01-HS-10803 (Dr. Newhouse) from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, and from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The authors thank Hocine Azeni, M.A., for statistical programming and Garrett Kirk, B.A., and Laurie Coots, B.A., for research assistance.

Dr. Donohue was a litigation consultant to GlaxoSmithKline on an unrelated matter. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Delate T, Mager DE, Sheth J, et al: Clinical and financial outcomes associated with a proton pump inhibitor prior-authorization program in a Medicaid population. American Journal of Managed Care 11:29–36, 2005Google Scholar

2. Fischer MA, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al: Medicaid prior-authorization programs and the use of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. New England Journal of Medicine 351:2187–2194, 2004Google Scholar

3. Smalley WE, Griffin MR, Fought RL, et al: Effect of a prior-authorization requirement on the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs by Medicaid patients. New England Journal of Medicine 332:1612–1617, 1995Google Scholar

4. Huskamp HA: Managing psychotropic drug costs: will formularies work? Health Affairs 22(5):84–96, 2003Google Scholar