Effectiveness of Two Methods of Obtaining Feedback on Mental Health Services Provided to Anonymous Recipients

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center had a devastating and long-lasting effect on the residents of New York City and the surrounding counties. Initial mental health needs assessments estimated that 3.1 million of these residents would experience emotional distress ( 1 ) and approximately 520,000 would experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ( 2 ). Although epidemiological surveys noted a decline in PTSD among Manhattan residents from 7.5 to .6 percent in the six months after the event ( 3 ), 40 percent of New Yorkers who used disaster-related crisis counseling during the two years after the attacks continued to report symptoms suggestive of at least subthreshold PTSD, depression, or both ( 4 ).

In response to the initial needs assessment, the New York State Office of Mental Health (NYOMH) used funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to develop Project Liberty, a program that provided free community-based, anonymous crisis counseling, referral, and information services to those affected by the attacks ( 5 ). Given the scope of Project Liberty and the possible need for future broad-scale responses to disasters, NYOMH obtained feedback from participants. Feedback was obtained under challenging circumstances: Project Liberty services were ongoing and service recipients were anonymous to evaluators. This article reports whether offering a brief anonymous questionnaire affected rates of agreement to participate in a confidential telephone interview and whether individuals with different demographic characteristics were more likely to participate in one feedback method or the other.

Methods

NYOMH selected eight sites to participate in the recipient-feedback pilot. These sites consistently served high numbers of individuals and differed from one another geographically, culturally, and ethnically. To explore whether offering a brief questionnaire affected rates of participation in a telephone interview, the evaluators then further divided these eight sites, counterbalancing demographic characteristics of service recipients and indicators of how well sites were functioning, into four sites to offer participation in a telephone interview only and four to offer each service recipient both the telephone interview and the brief questionnaire. Mount Sinai School of Medicine evaluators met with staff at each site to conduct training on the forms and procedures for approaching potential participants.

After measurement development and protocol approval by Mount Sinai School of Medicine's and NYOMH's institutional review boards, the study was conducted between January and April 2003. During this time, counselors at participating sites offered all English- and Spanish-speaking adults who used Project Liberty individual crisis counseling the opportunity to evaluate their service. If respondents agreed to a telephone interview, they could hand in completed (signed and sealed) permission-to-contact forms to their counselors to send on to evaluators, or they could complete forms later and mail them in. If respondents agreed to complete a brief questionnaire, they were given a copy to complete immediately or send in later. Training was provided to counselors so they would be familiar with the purpose of the evaluation and be able to answer any questions from recipients.

Researchers from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, in consultation with NYOMH and with other evaluators, developed the permission-to-contact form, along with a 102-item, 45-minute telephone interview (for which participants received $20) and the 32-item, brief, ten-minute questionnaire. The permission-to-contact form gathered contact information for individuals who expressed a willingness to participate in a telephone interview. Telephone interview and brief questionnaire items were structured to reflect content used in prior surveys ( 3 , 6 ), including reasons for contacting Project Liberty, satisfaction with services, extent of symptoms and functional impairment, demographic information, and referral to other services. The telephone interview included additional items designed to gather more detailed information in each of these domains. Counselors provided research staff with daily reports of the number of Project Liberty service recipients approached, how many declined to take a form (permission-to-contact or brief questionnaire), how many agreed to take a form, and how many returned a sealed form for the counselor to forward to NYOMH.

Descriptive statistics characterized response rates for permission-to-contact forms, the telephone interview, and the brief questionnaire and to examine responses to items evaluating Project Liberty. Chi square goodness-of-fit analyses were used to compare demographic information from the telephone interview and brief questionnaire with demographic information for all individuals using services at the participating Project Liberty sites between February and April 2003.

Because Project Liberty services were anonymous, evaluators determined the number of individuals who were offered the opportunity to provide feedback by asking counselors to report the number of individuals who were offered a permission-to-contact form and brief questionnaire. Compliance with the administrative task of reporting the number of individuals who were offered each form was uneven; hence, we used data from the five sites that were most adherent to calculating response and refusal rates—three sites offered only permission-to-contact forms to clients and two sites offered both permission-to-contact forms and the brief questionnaire—for chi square analyses to examine whether distributing the brief questionnaire appeared to affect response rates for the permission-to-contact form.

Results

A total of 214 Project Liberty service recipients from eight sites completed permission-to-contact forms and agreed to be contacted regarding participation in the telephone interview. Of these, 134 (63 percent) returned the permission-to-contact form by mail, and 80 (37 percent) gave the form to the counselor. Of the 214 recipients, 153 (71 percent) completed the telephone interview; of these, 61 (40 percent) stated they had also completed a brief questionnaire. A total of 107 Project Liberty recipients from four sites returned the brief questionnaire; of these, 73 (68 percent) returned the brief questionnaire by mail, and the remainder gave it to their counselor. Completion of individual items ranged from 75 to 99 percent for the brief questionnaire and consistently more than 97 percent for the telephone interview.

Among the five sites most compliant in recording information on the number of clients approached to participate in the telephone interview, 974 service recipients were offered a permission-to-contact form. Of these, 155 (16 percent) forms were completed—92 (17 percent) of 536 at the three permission-to-contact-only sites compared with 63 (14 percent) of 438 at two sites where both the permission-to-contact form and the brief questionnaire were offered. Similarly, at the two sites most adherent to recording the number of clients who received the brief questionnaire, 441 service recipients were offered the brief questionnaire, and 63 questionnaires (14 percent) were completed.

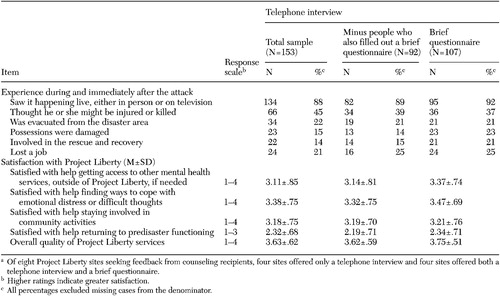

Both the telephone interview and brief questionnaire sampled men and women, those whose preferred language was English or another language, and individuals of varying races and ethnicities in the proportions generally expected given the demographic characteristics of all individuals served by Project Liberty at sites participating in the study. Responses on the brief questionnaire and telephone interview regarding experiences after the World Trade Center attacks and satisfaction with Project Liberty services yielded similar responses, which suggested that the methods gathered comparable information ( Table 1 ).

|

a Of eight Project Liberty sites seeking feedback from counseling recipients, four sites offered only a telephone interview and four sites offered both a telephone interview and a brief questionnaire.

Discussion

This report describes the means used to evaluate anonymous mental health services as they were being developed and refined in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, on the World Trade Center. Conclusions from this convenience sample must be taken as preliminary. Participation rates for the brief questionnaire and telephone interview were at best modest (less than 20 percent). However, among individuals who indicated a willingness to participate in a telephone interview, nearly three-quarters did so. Gender, racial and ethnic groups and reimbursement for time spent during the telephone interview were not associated with a greater likelihood of participating in either the telephone interview or brief questionnaire. Information obtained via each method was similar and demonstrated good response variability, and offering both methods did not adversely impact participation rates in either. These findings suggest that both methods represent feasible ways of obtaining feedback from anonymous service recipients who are willing to participate. That nearly two-thirds of participants chose to return their forms by mail underscores the utility of having multiple means of obtaining feedback.

Because responses to both methods were similar and individuals with different demographic characteristics did not seem to prefer one over the other, future investigators interested in obtaining satisfaction information may prefer the less expensive brief questionnaire, which cost $7 per returned survey. On the other hand, if investigators want additional information, such as ongoing symptoms and problems that individuals experienced after the attacks, they may need to conduct a more expensive telephone interview, which cost $190 per interview, including a $20 payment per participant in our evaluation. Given the challenge of obtaining participant evaluation while Project Liberty services were ongoing and service recipients were anonymous, we found the response rates disappointing but not surprising.

Conclusions

Although the low response rate was bad news for this evaluation, it served as an indicator that future evaluations need to incorporate methods to maximize response rates and to maintain provider adherence to administrative tasks critical to the evaluation. In addition, future providers of postdisaster services may consider the tradeoff between providing these services anonymously versus using unique identifiers that allow for more comprehensive service evaluation through time.

Acknowledgments

This evaluation was funded by grant FEMA-1391-DR-NY (titled "Project Liberty: Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program") to New York State from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration administered the grant. The authors express their appreciation to Katherine Shear, M.D.

1. New York State Office of Mental Health: Project Liberty Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program, Regular Services Program Application. FEMA-1391-DR-NY. Albany, New York State Office of Mental Health, 2001Google Scholar

2. Herman D, Susser E, Felton C: Rates and Treatment Costs of Mental Disorders Stemming From the World Trade Center Terrorist Attacks: An Initial Needs Assessment. Albany, New York State Office of Mental Health, 2002Google Scholar

3. Galea S, Vlahov D, Resnick H, et al: Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology 158:514-524, 2003Google Scholar

4. Jackson CT, Allen G, Essock SM, et al: Clusters of event reactions among recipients of Project Liberty mental health counseling. Psychiatric Services 57:1271-1276, 2006Google Scholar

5. Felton CJ: Project Liberty: a public health response to New Yorkers' mental health needs arising from the World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 79:429-433, 2002Google Scholar

6. Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 346:982-987, 2002Google Scholar