Use of Outpatient Mental Health Services by Depressed and Anxious Children as They Grow Up

Despite the considerable impairment associated with major mental disorders, many affected individuals do not seek treatment in any given year ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). Individuals with depressive disorders who do not seek care in the year following onset delay seeking care by an average of six years. Earlier onset is associated in epidemiologic samples with greater delay in seeking care ( 2 , 4 ).

Childhood-onset disorders tend to be more symptomatically persistent and impairing than later-onset disorders ( 5 , 6 ). In addition to both externalizing and internalizing problems, impairment, and self- or caretaker-reported need for services, factors associated with the use of mental health treatment by children and adolescents include high family income ( 7 , 8 ), family stress ( 9 ), and membership in a single-parent family ( 10 ). Conversely, in the United States, members of racial or ethnic minority groups, including blacks and Hispanics, are less likely than whites to obtain treatment, given need ( 8 , 9 , 11 , 12 ).

Most studies of treatment utilization among children and adolescents have measured psychopathology with global measures of distress ( 11 ), externalizing and internalizing symptom dimensions ( 9 , 12 ), or self-reports or caregiver reports of need for services ( 12 ). Few have considered diagnoses made according to modern criteria ( 8 ). Further, follow-up periods have typically ranged from one to five years ( 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). Thus data are limited concerning longer-term patterns or determinants of treatment utilization after the onset of childhood mental disorders.

Existing research on lifetime treatment utilization by adults that has considered childhood-onset disorders has tended to rely on retrospective dating of disorder onsets ( 3 , 4 ). By contrast, we examined lifetime outpatient mental health service use in a longitudinally assessed cohort originally ascertained in childhood. Cohort members were ascertained for having major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, or no lifetime mental disorder up to the time of ascertainment. Cohort members underwent rigorous diagnostic evaluation as children and completed follow-up assessments of psychiatric status and role functioning in adulthood.

The Behavioral Model of Health Services Use ( 14 , 15 ) identifies three categories of predictors of utilization: predisposing, enabling, and need. Predisposing factors include personal characteristics (for example, gender, age, marital status, and a past history of illness and care seeking). Gender and age have been associated consistently with patterns of seeking care, in part because they confer differential risks of illness ( 15 ).

Other predisposing factors locate individuals within existing social structures (for example, race or ethnicity and education). Besides being a marker for culturally influenced attitudes toward health care, and perceived or actual treatment by care providers, race or ethnicity may be a marker for social class factors related to the affordability and accessibility of care ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 16 , 17 ). Education may influence knowledge and attitudes toward care but tends also to be associated with higher income, greater access to insurance coverage, and perhaps greater skill in negotiating health care systems ( 15 , 18 , 19 ).

Enabling factors include income, insurance, usual source of care, and provider availability, which make utilization more affordable and logistically easier ( 14 , 16 , 18 , 19 ). Research concerning predictors of utilization can clarify whether treatment for childhood- and adolescent-onset mental disorders is primarily based on need defined by diagnosis or impairment (in other words, is equitably distributed) ( 14 ) or whether predisposing or enabling factors contribute substantially to service utilization ( 16 ).

We examined utilization of outpatient mental health treatment into adulthood by childhood diagnosis. We also considered additional need, indexed by onsets of comorbid psychiatric disorders over a follow-up period of ten to 15 years and global life-time impairment. In addition, we examined predisposing characteristics, including gender, pubertal status, and race and ethnicity, which were by definition fixed at initial recruitment of respondents, and age, marital status, and educational attainment at follow-up. Enabling characteristics ( 8 , 9 ) included past-year personal and household income. In addition, although it does not fit neatly into the categories of need or predisposing and enabling factors, we examined the potentially confounding effects of length of follow-up, because this variable was strongly associated with childhood diagnosis.

We considered any versus no treatment and, among utilizers, treatment duration. Several hypotheses were investigated.

First, we hypothesized that the strongest predictor of utilization would be need indexed by childhood diagnosis and that major depression would predict highest utilization ( 5 , 6 , 20 ), anxiety disorders would predict intermediate utilization ( 4 ), and having met criteria for no disorder at ascertainment would predict lowest utilization.

Second, we hypothesized that additional need characteristics, including episodes of mood and anxiety disorders during the follow-up period and greater global impairment, would predict increased utilization to a lesser degree than childhood diagnosis. Conversely, substance dependence and antisocial personality disorder during the follow-up period would predict reduced utilization because of low levels of problem recognition and motivation for treatment and a tendency for some clinicians to be pessimistic about treatment effectiveness for affected individuals ( 4 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ).

Third, we hypothesized that predisposing characteristics predicting increased utilization would include female gender, postpubertal status (Tanner stages IV and V, versus I through III), and white or Caucasian race and ethnicity ( 16 , 31 , 32 ), all of which were by definition fixed at ascertainment. Additional predisposing characteristics that we hypothesized would predict increased utilization, which were measured at follow-up, included older age, being previously married, and having completed higher levels of education ( 18 , 19 , 33 ). In addition to having more opportunity to attain more advanced cognitive development, and therefore being more likely to be aware of their own needs for treatment, those who were postpubertal at ascertainment or older at follow-up have passed through greater proportions of the risk periods for onsets of most common mental disorders ( 20 ).

Fourth, we hypothesized that the enabling characteristics of increased personal and household income would be associated with increased utilization ( 34 ).

Methods

The institutional review board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons approved all study procedures.

Sample

We report results from a ten- to 15-year clinical follow-up ( 35 , 36 ) conducted between 1991 and 1997 of a cohort of prepubertal children and adolescents originally assessed between 1977 and 1985. At ascertainment 199 children met Research Diagnostic Criteria ( 37 ) for major depressive disorder, 65 had anxiety disorders without major depression, and 175 children determined never to have met criteria for any lifetime disorder up to the time of their initial ascertainment were included as a control group. Ill children were ascertained through child psychiatry treatment clinics for depression and anxiety at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center. Children for the control group were recruited contemporaneously with ill children through school systems, newspaper advertisements, and word of mouth ( 38 , 39 , 40 ).

All children were free of psychoactive substance use disorders at initial ascertainment. Children were excluded from all three diagnostic groups if they had been taking medications that could produce symptoms similar to those of depression (amphetamines or phenothiazines, for example) or interfere with hypothalamic or pituitary function. Other exclusionary conditions were severe medical illness, obesity (weight-to-height ratio above the 95th percentile), height or weight below the third percentile, clinical seizures or other major neurological illnesses, IQ less than 70, anorexia nervosa, autism, or schizophrenia.

Assessments

After providing written informed consent, respondents were assessed at follow-up with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime version (SADS-LA) ( 41 , 42 ) modified for DSM-III-R . Experienced, clinically trained interviewers blind to the study hypotheses administered one version of the SADS-LA to respondents about themselves and, with respondents' consent, a separate version to a parent to provide information about their child. In addition to extensive demographic and symptom information, the SADS-LA identified duration of lifetime outpatient treatment as none, short term (a consultation or single brief period), intermediate term (continuous treatment of at least six months or several brief periods), and long term (continuous treatment of several years or numerous brief periods). The interview also contained a semistructured query to assess total number of six-month periods during the follow-up interval in which any treatment was received. Project staff requested written consent to obtain medical records from directly interviewed respondents.

Senior clinicians made final diagnoses and derived average lifetime Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale scores on the basis of direct and informant SADS-LA interviews, medical records, and any other available information, using a best-estimate procedure ( 43 , 44 ). Each episode of each disorder was diagnosed separately, including dates of onset and duration. Diagnosticians also rated symptomatic severity and disorder-specific impairment (none, mild, moderate, or severe) for each episode.

Data analysis

We aggregated data from two sources—from respondents about themselves and from informants about respondents—for our outcome variable, outpatient treatment duration, using the "or" rule ( 45 , 46 ) and taking the maximum reported by either respondents or informants. Thus, if the respondent reported short-term treatment but the informant reported long-term treatment, or vice versa, the respondent was coded as having long-term treatment. Similarly, for the number of six-month periods of any treatment, we took the maximum reported by either respondents or informants. We considered data only from respondents concerning education, income, and marital status at follow-up because we believed self-report about these variables, some of which may be considered personal or sensitive, to be more valid than informant reports.

We compared continuous variables by childhood diagnosis using analyses of variance and evaluated categorical variables using contingency-table approaches with chi square tests. To adjust for the effects of additional need, predisposing, and enabling characteristics, we modeled utilization by childhood diagnosis with logistic regression, using a two-phase approach ( 47 ).

In the first phase, we examined any versus no treatment in binary models. In the second, we used multinomial models to examine the duration of utilization among treated respondents using short-term treatment as the referent outcome. Multinomial modeling generalizes from binary logistic regression by allowing more than two levels of a categorical outcome variable to be modeled simultaneously ( 48 ).

Each phase involved fitting three separate models. The first included only childhood diagnosis as a predictor, with one dummy variable denoting major depression, one denoting anxiety, and the control group as the referent category. In the second model (model A), we added the predisposing factors of race-ethnicity and pubertal status, both of which were associated with utilization at p<.10 and fixed at ascertainment, and evaluated changes in the odds ratios (ORs) for childhood diagnoses. We included pubertal status rather than age at ascertainment because these measures were highly correlated and subject-matter considerations ( 35 , 36 ) made developmental phase a more meaningful measure than age. We did not include gender because it was not associated with utilization in bivariate analyses. The third model (model B) added need, predisposing, and enabling characteristics determined at follow-up: episodes of disorder with onset over one year after ascertainment, average lifetime GAF score, education, past-year household income, age at follow-up, and length of follow-up.

In each phase, we used likelihood ratio statistics to evaluate whether need, predisposing, and enabling characteristics, which, according to results of Wald tests, did not retain independent statistical significance in the adjusted model, contributed (p<.10) to the prediction of utilization. Further, we evaluated the ORs for childhood diagnosis to determine whether deleted covariates were confounders, that is, whether their deletion changed the ORs for childhood diagnoses by 15 percent or more. Either a significant likelihood ratio test or identification of confounding by a covariate was sufficient to retain it in the model. We tested two-way interactions between childhood diagnosis and other respondent characteristics, with an alpha to stay of .05; however, because no interaction met this criterion, we report only main effect models. We performed all analyses using SAS-PC software, version 8.2 ( 49 ).

Results

Sample characteristics

The overall follow-up rate for a sample of 332 was 76 percent—78 percent for the childhood depression group, 74 percent for the childhood anxiety group, and 73 percent for the control group (differences were not significant). As Table 1 shows, 72 percent either completed SADS-LA interviews about themselves or had informants complete SADS-LA interviews about them. Seven additional respondents ascertained for depression committed suicide during the follow-up period; data from psychological autopsies performed on them were included in the calculation of overall follow-up rates. Another ten, whose data were also included in the overall follow-up rates, consented to only brief interviews covering demographic characteristics and diagnostic information. Completion of SADS-LA interviews differed neither by gender nor by pubertal status or age at ascertainment. SADS-LA completion rates were significantly higher among whites and members of other racial and ethnic groups than among blacks and Hispanics.

|

a Respondents either completed SADS-LA interviews about themselves or had a parent informant who completed the interviews.

Respondent characteristics by childhood diagnosis appear in Table 2 . Utilization was robustly predicted by childhood depression and anxiety. Respondents ascertained for childhood depression exhibited the highest levels of other need indicators, including additional mood disorder (83 percent), substance dependence (38 percent), and antisocial personality disorder (12 percent) with onsets over one year after ascertainment, and they had the lowest average lifetime GAF scores (mean±SD=63.6±13.0; possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning) of the three groups. With respect to predisposing characteristics, those ascertained for major depression in childhood were oldest at initial evaluation and follow-up and most often postpubertal, black, and with postsecondary education. Conversely, regarding enabling characteristics, those depressed as children also reported the lowest past-year household income.

|

Respondents ascertained for childhood anxiety had the highest prevalence (57 percent) of comorbid anxiety disorders over the follow-up period. Their average lifetime GAF scores were intermediate (67.7±12.1) between those of the childhood depression and the control groups (78.4±12.4). Regarding predisposing characteristics, respondents ascertained for childhood anxiety were predominantly prepubertal at initial evaluation and least likely to report postsecondary education.

Childhood diagnosis was associated with neither the predisposing factors of gender or marital status nor the enabling factor of personal past-year income at follow-up.

Need, predisposing, and enabling factors and utilization

Need. ORs for any outpatient treatment are given in Table 3 . Need indexed by childhood diagnosis was the strongest predictor, although ORs decreased substantially from the crude model (28.5 for depression, 7.0 for anxiety) to the adjusted models (13.2 for depression and 5.7 for anxiety in model B). Additional need factors independently associated with utilization in model B were onsets of additional mood disorder episodes (OR=2.6) and lower lifetime GAF score (OR=.6 per 10 points) but not onsets of additional anxiety, substance dependence, or antisocial personality disorders. Patterns were similar when we included, in turn, best estimates of clinical severity, disorder-specific impairment, and percentage of the follow-up period spent in episodes of disorder, instead of presence versus absence of postascertainment episodes, as need indices in the models.

|

Predisposing factors. White (versus black) race and ethnicity significantly predicted utilization. Pubertal status did not independently predict treatment but confounded associations of treatment with childhood diagnoses. Education neither predicted treatment nor confounded associations with childhood diagnosis.

Potential confounder. As anticipated, follow-up time confounded associations of treatment with childhood diagnoses.

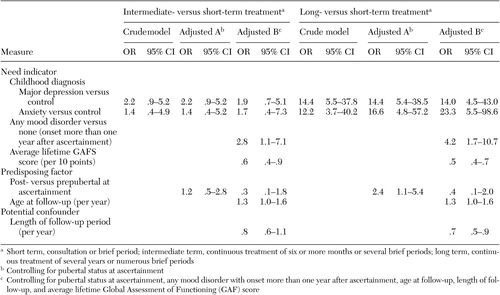

Treatment duration among utilizers

Need. ORs for treatment duration among utilizers appear in Table 4 . Associations of childhood depression (ORs= 2.2 for the crude model, 2.2 for model A, and 1.9 for model B) and anxiety (ORs=1.4, 1.4, and 1.7, respectively) with intermediate duration were modest and all CIs included the null value of 1.0. For long-term utilization, ORs associated with childhood depression were similar and large across all models (14.4 for crude and model A, 14.0 for model B). ORs for childhood anxiety were unstable because of small subgroup sizes, particularly for respondents postpubertal at ascertainment, but increased dramatically from crude (12.2) to adjusted models (16.6 in model A and 23.3 in model B).

|

Postascertainment onset of mood disorder—but not anxiety disorder, substance dependence, or antisocial personality disorder—and lower average GAF scores were associated with both intermediate and long durations of treatment. Again, patterns of results remained similar when we included severity, impairment, and percentage of follow-up time spent in episodes of comorbid disorders, instead of presence versus absence of disorders, as need indices in the models.

Predisposing factors. Race and ethnic identity and education were not retained in the models because they did not independently predict duration of treatment and did not confound associations of treatment duration with childhood diagnoses. Increasing age at follow-up was associated with increased odds of intermediate- and long-term utilization. Pubertal status independently predicted long-term treatment only in model A but confounded associations with childhood diagnosis in model B.

Potential confounder. Length of follow-up was not independently associated with intermediate-term treatment but was associated with decreased odds of long-term treatment. It also confounded associations with both childhood depression and childhood anxiety.

Discussion

Indices of need

Childhood diagnoses. Study hypotheses pertaining to associations of childhood diagnoses with utilization were partially supported. The strongest predictor of any treatment was original ascertainment for childhood depression, followed by childhood anxiety.

Treatment duration among utilizers presented a more complex picture. None of the ORs for intermediate-term treatment reached statistical significance. Conversely, the largest ORs related to long-term treatment were observed for childhood anxiety. Moreover, the ORs for childhood anxiety increased sharply from the crude to the adjusted models, particularly as predisposing factors, including pubertal status at ascertainment and age at follow-up and the confounding effects of length of follow-up, were taken into account.

Because of the small number of respondents selected for childhood anxiety, only four of whom were postpubertal at ascertainment, these estimates must be interpreted cautiously. However, the propensity for long-term treatment among individuals who had childhood anxiety disorders may be substantially more dependent on length of time as well as developmental phase (early or middle childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood) at risk than among those who had childhood major depression.

These findings could reflect the typically episodic course of depression compared with the more persistent course of anxiety disorders ( 35 , 50 , 51 , 52 ). However, in analyses controlling for percentage of follow-up period spent in episodes of disorders, time affected by anxiety disorders was not associated with utilization, nor did it confound the relationship of treatment to childhood diagnosis. Alternatively, respondents with childhood anxiety may have utilized more treatment because they were less successful in obtaining symptom relief and therefore had greater continuing need. Because we did not examine treatment outcomes, however, we cannot evaluate these explanations.

Additional need characteristics. Consistent with prior naturalistic follow-up studies ( 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 ), greater global impairment was associated with higher utilization. With respect to comorbidity, only additional onsets of mood disorders were independently associated with utilization. Moreover, while they partly explained differences by childhood diagnosis in utilization of any treatment, they did not explain associations of childhood diagnosis with treatment duration among utilizers.

Among respondents ascertained for childhood depression, the onset of additional episodes of mood disorders reflects, in large part, continuity and recurrence of depression ( 35 , 36 ). In addition, among respondents who were ascertained for childhood anxiety disorders, mood disorders—particularly depression—are associated with greater severity and treatment complexity ( 57 ). However, this association might be expected to yield confounding or interaction with childhood diagnosis, neither of which we observed. Perhaps neither respondents nor their providers addressed comorbidity during treatment. Thus respondents may have undertaken different episodes of treatment for different complaints. Alternatively, the study may have had inadequate power to detect confounding or interaction between childhood diagnosis and subsequent mood disorders because of small samples, particularly for the childhood anxiety group.

That substance dependence and antisocial personality disorder were unrelated to utilization over follow-up is inconsistent with several previous reports ( 3 , 4 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 58 ) and with our hypothesis of reduced treatment use in the presence of these disorders. However, the small sample of respondents who met criteria for antisocial personality disorder may not have provided adequate power to detect effects on utilization. Moreover, this sample was relatively young and may not have experienced sufficient duration of either substance dependence or antisocial personality disorder for these to have influenced utilization. Alternatively, for this severely ill cohort, attenuating effects of substance dependence and antisocial personality disorder could have been outweighed by high rates of comorbid emotional disorders. Of 91 respondents with substance dependence, only 11 had no other diagnoses; similarly, most of the 24 who met criteria for antisocial personality disorder also had mood or anxiety disorders.

Predisposing characteristics

Associations of childhood diagnosis with any utilization of treatment were not explained by predisposing characteristics, although the factor of race or ethnicity was independently predictive. That blacks were less likely than whites to utilize any care is compatible with previous findings from epidemiologic samples ( 14 , 16 , 58 ). This disparity may reflect sociocultural differences in attitudes toward mental illness and help seeking, including trust in providers ( 14 , 16 , 17 ). It may also reflect differential provider recognition (as a function of patient or provider race or ethnicity) of patients' distress, and therefore differential treatment and referral patterns. Black patients are less likely than white patients to have their emotional distress recognized by primary care providers ( 59 ). However, whereas white primary care physicians in New England were twice as likely as black providers to diagnose depression ( 60 ), provider race or ethnicity was not associated with detection of depression in the Medical Outcomes Study ( 61 ).

We surveyed a subsample of these respondents about barriers to treatment for mental health and substance use disorders (Goldstein RB, Weissman MM, Olfson M, et al., 1998, unpublished data). We observed no differences by race and ethnicity in endorsement of financial, attitudinal, logistical (such as transportation), linguistic, or religious barriers. However, we found that Hispanic respondents were significantly more likely than the other racial or ethnic groups to believe that treatment was not available and, among parenting respondents, to endorse the need for child care. These observations, together with those reported by others ( 14 , 16 , 17 ), underscore the need to clarify and address the factors underlying racial and ethnic differences in seeking care.

The finding that gender and education were not associated with utilization is inconsistent with numerous studies identifying women and better-educated individuals as higher utilizers of both general medical and mental health services ( 14 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 32 , 33 , 34 ). We have identified no clear explanation for our results. Perhaps the severity of respondents' need, or the socialization of those ill at ascertainment to seek care early in life, overwhelmed these potential demographic differences in seeking care.

Limitations

Although this is the largest longitudinal study of treatment utilization among individuals ascertained for childhood mental disorders, the small sizes of some subgroups constrain our ability to detect differences in utilization. Of particular concern are possible interactions between childhood diagnosis and other respondent characteristics with respect to treatment duration. In addition, lifetime service utilization was assessed ten to 15 years after ascertainment. Although the availability of diagnostic data from childhood is a strength that distinguishes this study, the length of the follow-up period increases the potential for recall and reporting biases. Such biases could either create spurious associations or obscure genuine ones with respondent characteristics.

We did not inquire into predisposing characteristics, such as attitudes toward treatment, nor enabling characteristics, such as health insurance coverage, provider availability, or usual sources of health care over the follow-up period. The enabling factors of personal and household income, which did not predict utilization, were ascertained only for the year preceding the interview. That time frame may not have accurately reflected respondents' financial status over the follow-up period, although past-year income is a proxy for recent insurance coverage and recent ability to afford services ( 62 ). We also did not ascertain why respondents utilized particular episodes of treatment, treatment outcomes, or why respondents terminated treatment.

Another limitation involves our ascertainment of respondents ill as children from tertiary care treatment clinics. Because past use of mental health services is a powerful predictor of subsequent use ( 63 , 64 ), the generalizability of our findings to samples from nonclinical sources is unclear.

Conclusions

The strongest predictor of both any utilization of outpatient treatment and treatment duration was need, particularly as defined by childhood diagnosis. We identified high rates and persistence of utilization among respondents ascertained for childhood depression and childhood anxiety. Utilization was lower among black than among white respondents. Our findings suggest a need for the development of strategies to maximize the uptake of effective, culturally relevant treatments. Culturally sensitive public health initiatives that specifically target individuals from ethnic minority groups with childhood-onset disorders are needed to increase awareness of treatment availability.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an Aaron Diamond Foundation postdoctoral research fellowship to Dr. Goldstein, by a senior investigator award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (Myrna M. Weissman, Ph.D., principal investigator), and by grant R01-MH50666 from the National Institute of Mental Health (Myrna M. Weissman, Ph.D., principal investigator). The authors express their appreciation to Dr. Weissman for her invaluable guidance on the conceptualization of this study and comments on drafts of this article and to Phillip B. Adams, Ph.D., for his contributions to the analytic methodology.

1. Olfson M, Kessler RC, Berglund PA, et al: Psychiatric disorder and first treatment contact in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1415-1422, 1998Google Scholar

2. Wang PS, Berglund PA, Olfson M, et al: Delays in initial treatment contact after first onset of a mental disorder. Health Services Research 39:393-415, 2004Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Berglund PA, et al: Patterns and predictors of treatment seeking after onset of a substance use disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:1065-1071, 2001Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Olfson M, Berglund PA: Patterns and predictors of treatment contact after first onset of psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:62-69, 1998Google Scholar

5. Kovacs M: Presentation and course of major depressive disorder during childhood and later years of the life span. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:705-715, 1996Google Scholar

6. Giaconia RM, Renherz HZ, Silverman AB, et al: Ages of onset of psychiatric disorders in a community population of older adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33:706-717, 1994Google Scholar

7. Cunningham PJ, Freiman MP: Determinants of ambulatory mental health services use for school-age children and adolescents. Health Services Research 31:409-427, 1996Google Scholar

8. Wu P, Hoven C, Cohen P, et al: Factors associated with use of mental health services for depression by children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 52:189-195, 2001Google Scholar

9. Zwaanswijk M, van der Ende J, Verhaak PFM, et al: Factors associated with adolescent mental health service need and utilization. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:692-700, 2003Google Scholar

10. Laitinen-Krispin S, van der Ende J, Wierdsma AI, et al: Predicting adolescent mental health service use in a prospective record-linkage study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1073-1080, 1999Google Scholar

11. Kodjo C, Auinger P: Predictors for emotionally distressed adolescents to receive mental health care. Journal of Adolescent Health 35:368-373, 2004Google Scholar

12. Mandell DS, Boothroyd RA, Stiles PG: Children's use of mental health services in different Medicaid insurance plans. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30:228-237, 2003Google Scholar

13. Kumpulainen K, Rasanen E: Symptoms and deviant behavior among eight-year-olds as predictors of referral for psychiatric evaluation by age 12. Psychiatric Services 53:201-206, 2002Google Scholar

14. Goodwin R, Andersen RM: Use of the behavioral model of health care use to identify correlates of use of treatment for panic attacks in the community. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37:212-219, 2002Google Scholar

15. Andersen R, Newman JF: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 51:95-124, 1973Google Scholar

16. Gallo JJ, Marino S, Ford D, et al: Filters on the pathway to mental health care: II. sociodemographic factors. Psychological Medicine 25:1149-1160, 1995Google Scholar

17. Rogler LH, Cortes DE: Help-seeking pathways: a unifying concept in mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:554-561, 1993Google Scholar

18. Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al: Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:603-613, 2005Google Scholar

19. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629-640, 2005Google Scholar

20. Robins LN, Locke BZ, Regier DA: An overview of psychiatric disorders in America, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

21. Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Kleber HD, et al: Heterogeneity of psychiatric diagnosis in treated opiate addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:161-166, 1982Google Scholar

22. Frosch JP: The treatment of antisocial and borderline personality disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:243-248, 1985Google Scholar

23. Gabbard GO, Coyne L: Predictors of response of antisocial patients to hospital treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1181-1185, 1987Google Scholar

24. McLellan AT, Druley KA: The readmitted drug patient: evidence of failure or gradual success? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 28:764-766, 1977Google Scholar

25. Paris J: Antisocial personality disorder: a biopsychosocial model. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 41:75-80, 1996Google Scholar

26. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Google Scholar

27. Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH: Influence of nondepressive psychiatric symptoms on whether patients tell a doctor about depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:640-644, 1989Google Scholar

28. Bucholz KK, Homan SM, Helzer JE: When do alcoholics first discuss drinking problems? Journal of Studies on Alcohol 53:582-589, 1992Google Scholar

29. Fiorentine R, Anglin MD: Perceived need for drug treatment: a look at eight hypotheses. International Journal of the Addictions 29:1835-1854, 1994Google Scholar

30. Kaskutas LA, Weisner C, Caetano R: Predictors of help seeking among a longitudinal sample of the general population, 1984-1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 58:155-161, 1997Google Scholar

31. Pearse WH: The Commonwealth Fund Women's Health Survey: selected results and comments. Women's Health Issues 4:38-47, 1994Google Scholar

32. Weisman C: Women's use of health care, in Women's Health: The Commonwealth Fund Survey. Edited by Falik M, Collins KS. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996Google Scholar

33. Thoits PA: Differential labeling of mental illness by social status: a new look at an old problem. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 46:102-119, 2005Google Scholar

34. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al: Mental health care use, morbidity, and socioeconomic status in the United States and Ontario. Inquiry 34:38-49, 1997Google Scholar

35. Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, et al: Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA 281:1707-1713, 1999Google Scholar

36. Weissman MM, Wolk S, Wickramaratne P, et al: Children with prepubertal-onset major depressive disorder and anxiety grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:794-801, 1999Google Scholar

37. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:773-782, 1978Google Scholar

38. Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, et al: The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interviews. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:696-702, 1985Google Scholar

39. Goetz RR, Puig-Antich J, Ryan N, et al: Electroencephalographic sleep of adolescents with major depression and normal controls. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:61-68, 1987Google Scholar

40. Puig-Antich J, Lukens E, Davies M, et al: Psychosocial functioning in prepubertal major depressive disorders: I. interpersonal relationships during the depressive episode. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:500-507, 1985Google Scholar

41. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:837-844, 1978Google Scholar

42. Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ, Klein DF, et al: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Lifetime Version (modified for the study of anxiety disorders): rationale and conceptual development. Journal of Psychiatric Research 20:317-325, 1986Google Scholar

43. Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson WD, et al: Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodologic study. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:879-883, 1982Google Scholar

44. Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne PJ, et al: Offspring of depressed parents: 10 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:932-940, 1997Google Scholar

45. Bird HR, Gould M, Staghezza B: Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:78-85, 1992Google Scholar

46. Jensen PS, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, et al: Parent and child contributions to the diagnosis of mental disorder: are both informants always necessary? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1569-1579, 1999Google Scholar

47. Diehr P, Yanez D, Ash A, et al: Methods for analyzing health care utilization and costs. Annual Review of Public Health 20:125-144, 1999Google Scholar

48. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 2000Google Scholar

49. SAS Statistical Software, Version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1999Google Scholar

50. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al: Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:229-233, 2000Google Scholar

51. Woodman CL, Noyes R Jr, Black DW, et al: A 5-year follow-up study of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:3-9, 1999Google Scholar

52. Yonkers KA, Bruce SE, Dyck IR, et al: Chronicity, relapse, and illness-course of panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder: findings in men and women from 8 years of follow-up. Depression and Anxiety 17:173-179, 2003Google Scholar

53. Keel PJ, Dorer DJ, Eddy KT, et al: Predictors of treatment utilization among women with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:140-142, 2002Google Scholar

54. Klein DN, Schatzberg AF, McCullough JP, et al: Age of onset in chronic major depression: relation to demographic and clinical variables, family history, and treatment response. Journal of Affective Disorders 55:149-157, 1999Google Scholar

55. Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, et al: A 20-year longitudinal observational study of somatic antidepressant treatment effectiveness. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:727-733, 2003Google Scholar

56. Yonkers KA, Ellison JM, Shera DM, et al: Description of antipanic therapy in a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 16:223-232, 1996Google Scholar

57. Slaap BR, denBoer JA: The prediction of nonresponse to pharmacotherapy in panic disorder: a review. Depression and Anxiety 14:112-122, 2001Google Scholar

58. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77-84, 2002Google Scholar

59. Sleath B, Svarstad B, Roter D: Patient race and psychotropic prescribing during medical encounters. Patient Education and Counseling 34:227-238, 1998Google Scholar

60. McKinlay JB, Lin T, Freund K, et al: The unexpected influence of physician attributes on clinical decisions: results of an experiment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 43:92-106, 2002Google Scholar

61. Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, et al: Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:381-388, 2000Google Scholar

62. Simpson L, Owens PL, Zodet MW, et al: Health care for children and youth in the United States: annual report on patterns of coverage, utilization, quality, and expenditures by income. Ambulatory Pediatrics 5:6-44, 2005Google Scholar

63. Dew MA, Bromet EJ, Schulberg HC, et al: Factors affecting service utilization for depression in a white collar population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 26:230-237, 1991Google Scholar

64. Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet EJ, et al: Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders 14:223-234, 1988Google Scholar