Effects of Serious Mental Illness and Substance Abuse on Criminal Offenses

The widely held belief that serious mental illness has been "criminalized" is based mainly on findings that persons with serious mental illness are more likely to be arrested ( 1 ) and are overrepresented in jails ( 2 ) and prisons ( 3 ). Why persons with serious mental illness are more likely to be arrested and incarcerated is unclear, but a literal and popular interpretation of the criminalization hypothesis implies two possibilities. First, symptoms of serious mental illness have become de facto criminal offenses; that is, persons with serious mental illness are arrested and incarcerated for displaying psychiatric symptoms. Second, symptoms of serious mental illness motivate or otherwise cause actual criminal offenses.

This literal interpretation of the criminalization hypothesis is apparent in a recent "Where We Stand" position paper on the criminalization of mental illness issued by the National Alliance on Mental Illness: "NAMI believes that persons who have committed offenses due to states of mind or behavior caused by a brain disorder require treatment, not punishment…. NAMI believes that mental health systems have an obligation to develop and implement systems of appropriate care for individuals whose untreated brain disorders may cause them to engage in inappropriate or criminal behavior" ( 4 ).

In fact, what little empirical research exists on this particular interpretation of the criminalization hypothesis has produced no consensus ( 5 ). Supporting evidence for a literal interpretation would seem to require a convincing demonstration that serious mental illness is directly linked with behavior that leads to arrest and incarceration, a higher standard of proof than currently offered by correlational research. For example, Mc-Niel and colleagues ( 6 ) found that San Francisco jail inmates who had received a psychiatric diagnosis were more likely to be charged with felonies and violent crimes. However, these researchers were appropriately cautious about making a causal inference in noting that their findings represented a failure of the mental health care system only "to the extent that the crimes committed by these individuals are related to their untreated mental or substance abuse disorders."

The purpose of our retrospective study was to determine the effects of serious mental illness and substance abuse on the criminal offenses of a group of community residents with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance abuse disorders. These community residents were participants in the Hawaii Jail Diversion Project, part of a multisite, national study comparing the functional outcomes of persons diverted out of jail and into mental health and substance abuse services with the outcomes of a control group of persons arrested and jailed ( 7 ). The Hawaii site consisted of a "postbooking" jail diversion program on the island of Oahu, in which individuals arrested and charged with a criminal offense were diverted out of jail and into appropriate services at arraignment. Control sites were on the islands of Maui and Hawaii, where individuals were arrested, charged, and jailed. For purposes of our later discussion, the type of jail diversion program on Oahu should be contrasted with a "prebooking" program in which persons are not arrested but are diverted into appropriate services by frontline personnel—typically by police officers and (importantly) often on a mental health emergency basis.

Methods

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the University of Hawaii, Manoa, and from the Hawaii Department of Health. Participants signed an IRB-approved informed consent form before joining the study.

Participants were 113 community residents who were serial recruits of the Hawaii Jail Diversion Project between May 1998 and August 2001. They were arrested for a criminal offense (hereafter referred to as the "index offense") and met inclusion criteria for the project: current serious mental illness as indicated by a DSM-IV axis I schizophrenia spectrum or major mood disorder and co-occurring substance use disorder. Participants' mean±SD age was 37.6±8.8 years, and 82 (72 percent) were male. Among racial categories, 46 participants (41 percent) were white, 33 (29 percent) were Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders, nine (8 percent) were multiracial, and seven (7 percent) were Asian. Overall, participants had 12.1±2.2 years of education. The distribution among diagnostic categories was 45 (40 percent) with major depressive disorder, 39 (34 percent) with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and 29 (26 percent) with bipolar disorder.

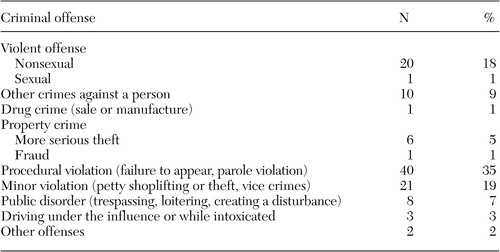

Table 1 shows the frequency of the different types of index offenses committed by participants in the study. In cases of multiple offenses committed, only the most serious was tabulated. First, note that there were relatively few violent offenses, which was to be expected given that jail diversion typically is not initiated with violent felony offenders. Also, note that the most common offense was a procedural violation, usually a failure to appear in court for a disposition hearing.

|

Information on the cause of the index offense was obtained by asking participants three or four probe questions during the project's intake interview, which occurred within seven days of their arrest: Why did you [offense]? Is there anything else you can tell me about [offense]? Do I know everything I need to know to understand why you [offense]? If not, what else do I need to know?

Participants' responses to the probe questions were written down verbatim for future analysis. Three of us (RL, AC, KC) read descriptions of the index offenses as described by the participants and as recorded in police arrest reports, along with the participants' explanations for the offenses. We then used identical 5-point scales to estimate independently the probability that the index offense was the result of the direct or indirect effects of serious mental illness or substance abuse.

The rating scales consisted of probabilities with descriptive anchors: 0, definitely not; 25, probably not; 50, possibly; 75, probably; and 100, definitely. A direct effect of serious mental illness was defined as the specific influence of concurrent delusions or hallucinations on the criminal offense identified in the police arrest report. An indirect effect of serious mental illness was any other symptom-based influence, such as confusion, depression, thought disorder, or irritability. A direct effect of substance abuse was defined as the influence of being intoxicated or high on the criminal offense identified in the police arrest report. An indirect effect of substance abuse was indicated by an offense committed to obtain alcohol or drugs or to obtain money for alcohol or drugs.

Results

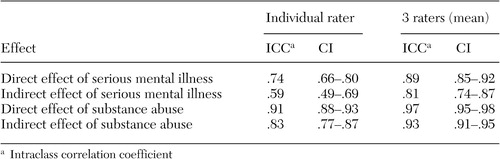

We assessed the reliability of our estimates of the direct and indirect effects of serious mental illness and substance abuse on the index offense by calculating intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and their 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs) for individual raters and for the mean of three raters. These values are shown in Table 2 . The reliability of estimates by individual raters was very good, except for the indirect effect of mental illness, which was only adequate. Follow-up discussions among the three raters indicated that the greatest disagreements occurred when participants claimed to have forgotten about disposition hearings, which one or two raters were more likely to attribute to the indirect effects of serious mental illness. In light of this, we used the more reliable mean of the three raters' estimates for each of the four effects in the analyses that follow.

|

The mean estimate of the direct effect of serious mental illness was significantly correlated with the mean estimate of the indirect effect of serious mental illness (r=.51, p<.001); this was also true for the two mean estimates of the effects of substance abuse (r=.24, p<.05). However, mean estimates of the effects of serious mental illness were not significantly correlated with mean estimates of the effects of substance abuse, which may indicate some validity in our distinction between the effects of serious mental illness and substance abuse on the index offense.

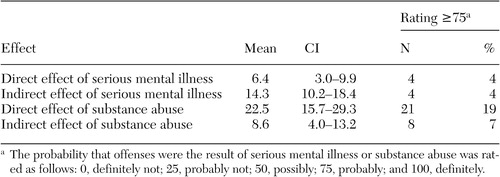

One of our first observations was that none of the 113 participants claimed to have been arrested for behavior that could be construed as a simple, unobtrusive display of psychiatric symptoms (talking to oneself, for example). Table 3 shows the mean probability estimate, CIs, and number of index offenses assigned a mean probability estimate greater than or equal to 75 (greater than or equal to "probably") for each of the four effects we assessed. The mean probability estimates can be interpreted as the general or overall effect of serious mental illness and substance abuse on the index offenses committed by participants in our sample. As can be seen, neither serious mental illness nor substance abuse was judged to have had much of an effect on the index offenses. Also, with the notable exception of the direct effect of substance abuse, very few offenses were assigned a mean probability estimate greater than or equal to 75 for any of the other three effects. (We note that all four of the index offenses assigned a mean estimate greater than or equal to 75 for the direct effect of serious mental illness were violent offenses motivated by delusions.) The relatively few offenses assigned a mean estimate greater than or equal to 75 further supported the impression that serious mental illness, in particular, had little effect on the participants' criminal offending.

|

However, almost a quarter (23 percent) of the index offenses were rated as probably or definitely the direct or indirect result of substance abuse (three offenses were assigned a mean estimate greater than or equal to 75 for both substance abuse effects). A paired t test of the higher of the two respective effects for serious mental illness and substance abuse showed that the mean estimate of the overall effect of substance abuse, 26.3±38.9, was significantly greater than that of serious mental illness, 16.2±24.7 (t=2.24, df=112, p=.027). Similarly, a signed-rank test of the difference between these two estimates showed that 26 participants had higher estimates for substance abuse compared with seven participants who had higher estimates for serious mental illness, which was significant (z=3.13, p=.002). This result would seem to confirm once again that substance abuse has relatively greater influence than psychiatric symptoms on criminal offending ( 8 ) and may be an important factor in the increased levels of arrest and incarceration of persons with serious mental illness.

Discussion

Our findings do not support a literal interpretation of the criminalization hypothesis that serious mental illness has been criminalized through the unreasonable arrest of persons displaying or acting on their psychiatric symptoms—at least not in the case of our seemingly typical sample of post-booking jail diversion participants and their nondiverted counterparts.

This is not to say that serious mental illness cannot lead to criminal offending. Of the 113 index offenses committed by our participants, the four assigned an estimate greater than or equal to 75 for the direct effect of serious mental illness were violent offenses motivated by delusions. However, delusional violence is rare when considered in the context of the prevalence of delusions ( 9 ), and the actual contribution of delusions to the violence rates of persons with serious mental illness is unclear ( 5 ). In any case, substance abuse was responsible for a sizable minority of index criminal offenses committed by our participants and was a significantly more likely causal factor for criminal offending than serious mental illness.

The extent to which our findings inform the ongoing debate on the criminalization of mental illness is difficult to state precisely. As might be inferred from our earlier description, persons diverted in a prebooking jail diversion program conceivably could be more acutely symptomatic and therefore presumably more likely to display or act on their psychiatric symptoms than our postbooking participants and their counterparts. Although that remains to be seen, it is a possibility that must be given serious consideration when interpreting our generally negative findings.

The type of data on which our raters based their estimates also may be problematic for some. To accept our results as meaningful, one must first accept that mental health professionals can identify and separate the respective influences of serious mental illness and substance abuse on criminal offending on the basis of police reports and the patients' descriptions of what happened and why. Although this task seemed straightforward at the extremes of our scales (for example, "I'd been drinking all day and ended up getting in a fight"), it was less so at the midrange ("I didn't make [my court appointment] because I was confused about the day"). Subtle influences of serious mental illness on criminal offending easily could have been lost to our raters in these less obvious, midrange descriptions.

With these cautions in mind, our causal analysis of the criminal offenses committed by our participants seems to support the contention of Draine and colleagues ( 10 ) that mental illness is "criminalized" mostly to the extent that persons with serious mental illness have other, more powerful risk factors for crime (substance abuse, for example). Persons with serious mental illness may be overrepresented in jails and prisons, but we can offer little evidence from our postbooking sample that it was their illness that got them there.

We have presented a methodological approach to try to address the heart of the criminalization issue: whether serious mental illness per se is associated with behavior leading to arrest and incarceration. It was not, for the most part, in our sample of arrestees with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. A reasonable next step would be to apply our causal analysis to the criminal offenses of other psychiatric samples, especially those more acutely symptomatic than our participants were.

Conclusions

Unless it can be shown that factors unique to serious mental illness are specifically associated with behavior leading to arrest and incarceration, the criminalization hypothesis should be reconsidered in favor of more powerful risk factors for crime that are inherent in social settings occupied by persons with serious mental illness—risk factors such as unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and substance abuse ( 10 ). The overrepresentation of persons with serious mental illness in jails and prisons may not indicate a mental health care crisis as much as a public policy crisis. Jails and prisons may continue to be seen as the "psychiatric warehouses of the new millennium" ( 11 ) as long as risk factors for crime that are known to be widespread in psychiatric populations are not adequately addressed by community resources and services. The criminalization hypothesis, with its almost exclusive emphasis on mental health care issues, ultimately may be a distraction from more promising areas for intervention—substance abuse and the disadvantaged social settings common to many persons with serious mental illness.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grant SM-52121-01 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded to the Hawaii State Department of Health.

1. Tiihonen J, Isohanni M, Rasanen P, et al: Specific major mental disorders and criminality: a 26-year prospective study of the 1966 northern Finland birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:840-845, 1997Google Scholar

2. Teplin L: The prevalence of severe mental disorder among male urban jail detainees: comparison with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. American Journal of Public Health 80:655-656, 1990Google Scholar

3. Fazel S, Danesh J: Serious mental disorder in 23,000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet 359:545-550, 2002Google Scholar

4. The criminalization of people with mental illness, in Where We Stand. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 2001Google Scholar

5. Junginger J, McGuire L: Psychotic motivation and the paradox of current research on serious mental illness and violence. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:21-30, 2004Google Scholar

6. McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC: Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 56:840-846, 2005Google Scholar

7. Steadman HJ, Deane M, Morrissey J, et al: A SAMHSA research initiative assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 50:1620-1623, 1999Google Scholar

8. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393-401, 1998Google Scholar

9. Junginger J, Parks-Levy J, McGuire L: Delusions and symptom-consistent violence. Psychiatric Services 49:218-220, 1998Google Scholar

10. Draine J, Salzer M, Culhane D, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565-573, 2002Google Scholar

11. Faenza M: Statement on the criminalization of mental illness. News release. Alexandria, VA, National Mental Health Association, Sept 21, 2000Google Scholar