Economic Grand Rounds: Variation in Staffing and Activities in Psychiatric Inpatient Units

Until recently, Medicare paid psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric distinct part units (DPUs) of acute general hospitals on a cost basis subject to a fixed amount per discharge, regardless of case mix or market factors ( 1 ). The Balanced Budget Refinement Act (BBRA) of 1999 mandated the development of a patient-based per diem prospective payment methodology for all psychiatric inpatients, and in January 2005 nearly 1,900 U.S. psychiatric facilities began converting to prospective payment ( 2 ). Before the BBRA was introduced, little was known about the underlying sources of variation in the way that units are organized and staffed across the country. To assist in the development of the payment system, we conducted a survey of inpatient units to understand how these units are staffed and how intensively staff members spend their time caring for patients.

Analysis of the facilities and staff

Of the participating 40 facilities, 26 facilities (65 percent) were acute general hospitals with psychiatric DPUs, 11 (28 percent) were private psychiatric hospitals, and three (8 percent) were public county and state psychiatric hospitals. We selected one to three psychiatric inpatient units in each facility, including 37 general adult units, 15 geriatric units, four medical-psychiatric units, one forensic unit, and eight specialty units—for example, dual psychiatric and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis).

The 40 facilities had a total of 165 different inpatient units, including adolescent and other non-Medicare units. Private and public hospitals differed markedly in the way they organized patients into distinct units. Two-thirds of all inpatient units in public facilities in our study were general adult units (eight of 12 units). No public hospitals that we studied had specialized psychiatric intensive care or dual diagnosis units, and only one had a geriatric or detoxification unit. However, the one public forensic unit in our study was similar in case mix to the psychiatric intensive care units in the private hospitals. Private facilities offered a wider variety of specialized care in their 118 inpatient units: 31 child and adolescent units, 18 geriatric units, ten dual diagnosis units, eight psychiatric intensive care units, and seven detoxification units. Private acute general hospitals were more than twice as likely as private psychiatric hospitals to have organized geriatric units and were the only facilities with medical-psychiatric units.

All staff on each inpatient unit involved in our study were surveyed during a seven-day period between 2001 and 2003. Staff reported their shift times by activity, which we converted to full-time equivalent (FTE) hours. More information on sampling frame and survey design is available ( 3 ). Staff were grouped into nine categories: licensed nurses (registered nurses, licensed vocational nurses, and licensed practical nurses), psychiatrists, medical physicians, case or social workers, mental health specialists (certified nursing assistants and psychiatric nursing aides), psychologists, therapists, resident physicians, and clerks. Consulting medical physicians and other staff visiting patients on the unit filled out a consultant log specific to each patient and were included in staffing times.

Findings

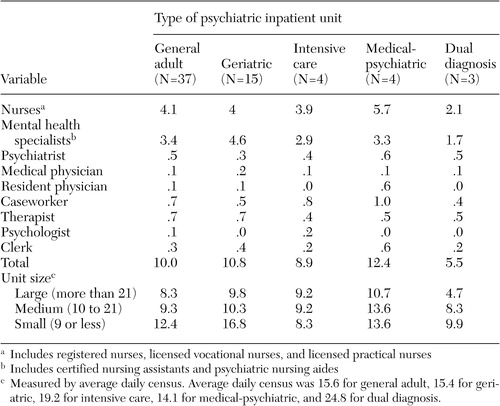

As shown in Table 1 , psychiatric staff of all types averaged ten to 11 hours per patient per day on general adult and geriatric units. Compared with staff intensity on general adult units, daily staff intensity per patient was 10 percent less on intensive units and almost 50 percent less on dual diagnosis units. Medical-psychiatric units exhibited the greatest staffing intensity (12.4 hours per patient per day). As expected, nurses spent far more time in medical-psychiatric units than on general adult units (1.6 hours more per patient per day). Mental health specialists, by contrast, spent more time with patients on geriatric units than on general adult units (1.2 hours more per patient per day). Staffing intensity per patient varied far less among the other seven occupations. Psychiatrists and caseworkers spent more time per patient per day on medical-psychiatric units than on general adult units, and they spent somewhat less time with patients on geriatric units than on general adult units. Therapists, by contrast, spent less time with patients on medical-psychiatric units than on general adult units (.2 hour less per patient per day).

|

Staff intensity per patient varied inversely with the size of the unit, as measured by the average daily census. For general adult units, small units averaged 12.4 staff hours per patient per day, and large units averaged 8.3 hours per patient per day. Small geriatric units were the most time intensive of all, averaging 16.8 staff hours per patient per day. On geriatric units, nurses spent 2.5 times more time for each patient per day on small units than on large units; mental health specialists spent 1.3 times more time for each patient per day on small units than on large units. Staff logs reported one nurse to only two or three patients on some units on some days, because a nurse is required to be on the unit at all times, regardless of occupancy.

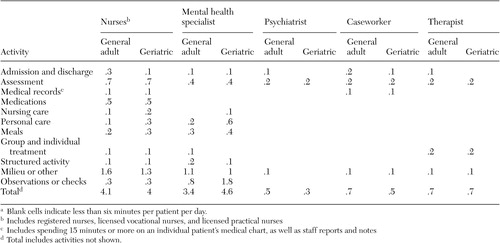

Table 2 shows staffing intensity per patient per day for general adult and geriatric units, by type of daily activity. Nurses spent the largest block of their time (about 40 percent) managing the milieu, which includes routine paperwork and change-of-shift activities. In both types of units, nurses spent another .7 hour assessing each patient on the unit during a 24-hour day and another .5 hour administering medications. Mental health specialists spent less time than nurses in activities such as admissions and assessment. By contrast, mental health specialists were more involved than nurses in personal care of patients, meals, and, especially, in checks (rounds or flows) and one-to-one observation. For example, on geriatric units, mental health specialists spent 1.8 hours per patient per day on checks and directly observing individual patients, whereas nurses spent only one-sixth as much time on these tasks (.3 hour per patient per day).

|

a Blank cells indicate less than six minutes per patient per day.

Other key staff spent far less time per patient per day while focusing on specific activities. Psychiatrists reported spending nearly one-half of their time assessing patients, which includes staff discussions about patient treatment plans. Caseworkers spent nearly equal amounts of their time on admissions and discharge planning and on assessing patients as they worked with them on postdischarge placement. Therapists spent .2 hour per patient either in assessment or group therapy.

Roughly 55 percent of staff time per patient per day on a general adult or geriatric unit was involved in psychiatric care, including assessment, medications, individual or group therapy, observation or checks, admissions or discharges, structured activities, and medical records. Nursing care related to medical needs, personal care, and meals accounted for 10 percent of nursing staff time on general adult units and 20 percent of nursing staff time on geriatric units. Milieu or other time not directly devoted to caring for individual patients took up 34 percent of staff time on general adult units and 25 percent of staff time on geriatric units.

Discussion and conclusions

Our research was based on original primary data from 40 psychiatric facilities and showed considerable variation in staffing time per patient on the average day. Managers in both general adult and specialized inpatient units felt that they were providing efficient, high-quality care. Yet, to our knowledge, no rigorous outcomes study has been conducted stratified by type of unit. Medical-psychiatric units are particularly staff intensive; yet no formal definition exists of such units. It would be difficult for Medicare to identify such units and pay higher per diems for patients treated in these units. Under the new per diem payment system, Medicare adjusts payment for comorbid conditions, but the list of conditions is limited and may underpay for patients in medical-psychiatric units ( 3 , 4 ). One of the critical issues for Medicare is whether beneficiaries are receiving better care in (possibly more expensive) specialized units. We encourage Medicare, under its congressionally mandated pay-for-performance initiative, to conduct demonstrations across facilities that use different unit organizational models.

We found that staffing intensity varied systematically by average daily census. Larger units, in particular, reap economies of scale by spreading nursing and aide staff across more patients. Before the new prospective payment system, Medicare based payment on a facility's average cost per patient, which was subject to a per-case ceiling and would have recognized the higher costs of smaller units. No payment adjustment exists in the new prospective system for smaller units. Reduced payment could force some units to close and restrict access to critical inpatient psychiatric care in already underserved areas.

Staffing and running an inpatient psychiatric unit are challenging because of the variety of staff involved and the range of activities. Unlike staff on routine medical-surgical floors, who care mainly for bedridden patients, staff on psychiatric units lead therapy groups; help provide and oversee meals in dining rooms; take patients off the unit for tests, "smoking breaks," and exercise groups; conduct regular checks of all patients; and constantly observe disoriented or dangerous patients. From our site visits, it was clear that units struggled with the most cost-effective way to ensure patient safety, either through periodic or one-on-one observation. Adding to the challenge is the extensive staff time that is sometimes required to accompany patients to court. These interruptions are highly varied and idiosyncratic to the unit's patient population, their service needs, and the way that the legal system interacts with the hospital in a particular locale. Public regulations restricting certain modes of restraint further add to staffing needs and costs for particularly difficult patients. Another constraining factor is the maximum ratio of patients to registered nurses that is mandated by California; this regulation may fail to reflect the widespread delegation and staffing flexibility that logically occurs on an inpatient psychiatric unit. More research is needed on best practices that match different types of staff to patients who have different nursing, psychiatric, and medical needs.

Our study had some limitations. Although staffing figures in our study pertain to all patients on the unit, geriatric units were oversampled and other units undersampled because of the focus on Medicare patients. Also, no official definitions of specialized units exist, and the results for these units may not represent the staffing in a particular hospital. Finally, because no case-mix adjustments to the staffing figures were made, all results are presented by unit type as a partial case-mix adjustment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fred Thomas, Ph.D., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Project Officer, for his support and comments on the research. This study was funded in part by the CMS, contract 500-95-0058, task order 13. The statements contained in this column are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CMS.

1. Cromwell, J, Harrow B, McGuire T: Medicare payment for psychiatric facilities: unfair and inefficient? Health Affairs 10(2):124-134, 1991Google Scholar

2. Medicare program; prospective payment system for inpatient psychiatric facilities; proposed rule. Federal Register 68:66920-66978, Nov 28, 2003Google Scholar

3. Cromwell, J, Maier J, Gage B, et al: Characteristics of high staff intensive Medicare psychiatric inpatients. Health Care Financing Review 26:103-117, 2004Google Scholar

4. Drozd E, Cromwell J, Gage B, et al: Patient casemix classification for Medicare psychiatric prospective payment. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:724-732, 2006Google Scholar