Pharmacological Treatment Patterns at Study Entry for the First 500 STEP-BD Participants

The psychopharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder varies widely ( 1 ). Among the standard agents, lithium and carbamazepine have tended to be used frequently in Europe and Canada, whereas valproate has been frequently prescribed in the United States ( 2 ). Furthermore, there is controversy as to which agents should be termed "mood stabilizers" and thus be used as primary treatments ( 3 ). In many settings, antidepressants are frequently used ( 2 , 4 , 5 ).

A great deal of controversy exists on this issue, because some data suggest that long-term antidepressant use may worsen the course of bipolar illness ( 6 ). In the community setting, antidepressant use appears particularly frequent, sometimes even in the absence of concomitant mood stabilizer use ( 2 ). Similarly, neuroleptics can be used more or less frequently depending on the agents and the settings in which patients with bipolar disorder are treated ( 5 , 7 , 8 ).

Part of this lack of consensus in practice reflects insufficient or inadequate research data. Studies also differ on the relative efficacy of antidepressants, neuroleptics, and mood stabilizers in bipolar disorder, and some data suggest that treatment guidelines are not followed in the community ( 8 ).

Previous studies of prescription patterns in bipolar disorder, based on both primary and tertiary U.S. psychiatric settings ( 2 , 9 , 10 ), have suggested that mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate are prescribed for 40 to 60 percent of patients and that at least one-half of patients receive antidepressants, mostly serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) or bupropion. More than one-half of patients tend to receive polypharmacy with three or more mood stabilizers, antidepressants, or antipsychotics, and only 20 percent or fewer are treated with mood stabilizer monotherapy.

Higher rates of both mood stabilizer and antidepressant use have been reported in a U.S. nonpsychiatric primary care clinical setting ( 11 ), where, in one study of 3,057 patient pharmacy records from a health plan, 72 percent of patients with bipolar disorder received antidepressants and 78 percent received mood stabilizers. In nonclinical community settings, one study from Europe found that only 6.9 percent of 317 persons with bipolar disorder took any psychotropic medication ( 12 ). In a community survey of 85,358 patients who used the Mood Disorder Questionnaire ( 13 ), only about 20 percent of those who scored positive on that scale for putative bipolar disorder were actually given a diagnosis of and treated for bipolar disorder.

There may also be national differences. In another study in the United Kingdom, only 14 percent of 63 patients at a tertiary care psychiatric setting received antidepressants, whereas use of mood stabilizers (51 percent) and antipsychotics (37 percent) was similar to that found in U.S. studies.

Previous studies were usually either small and well characterized or large but limited in data quality. In this study, we examined a large sample that is well characterized to provide data on prescribing patterns among patients with bipolar disorder in the community. This sample involves patients seen at entry into a large follow-up study, the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) collaborative study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). This study is not hypothesis driven but rather a descriptive report of the recent state of pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder. Such descriptive data are important in their own right, because they highlight specific issues that need to be better targeted in continuing medical education programs or better examined in research studies. Therefore, this report is unique in that it describes treatment patterns for different phases of bipolar disorder in a well-characterized cohort of patients with bipolar disorder.

Methods

STEP-BD is a multisite project funded by NIMH that was designed to evaluate the longitudinal outcome of patients with bipolar disorder ( 14 ). The overall study is composed of a large prospective naturalistic study, combined with specific randomized controlled trials. To enroll in STEP-BD, patients were required to be at least 15 years of age and to meet DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymia, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, or schizoaffective manic or bipolar disorder subtypes. Exclusion criteria were limited to the unwillingness or inability to comply with study assessments or the inability to give informed consent. Human subjects panels at all contributing sites approved the protocol, and all patients provided both oral and written consent before participation.

For the article presented here, we included the first 500 patients entered into STEP-BD, who were enrolled in 1998 through 1999. The data analyzed in this study were assessed at the time of study enrollment with a structured interview performed by trained clinician investigators experienced with the assessment and treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. These structured interviews, called the Affective Disorder Evaluation (ADE), consist of assessments of DSM-IV criteria for current depressive and manic symptoms, documentation of current medications, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) mood modules for past depression and mania, assessment of the number of previous mood episodes, the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) diagnostic interview for other psychiatric diagnoses and substance abuse, assessment of previous treatment trials and response to them, medical history, and current mental status examination. All interviewers were trained psychiatrists employed in academic bipolar specialty clinics who had been trained in STEP-BD procedures, as described elsewhere ( 14 ). Medication data were based on patient interview and medical records, when available.

Because the data presented here were based on the ADE and were collected before entry into STEP-BD, these practice patterns do not reflect the treatment algorithms of STEP-BD, but rather they reflect the baseline medications taken before entering STEP-BD—that is, standard clinical practice patterns in the community and in these clinics.

Rapid cycling was defined as more than four mood episodes in the previous year before evaluation by ADE and entry into STEP-BD. Past psychosis was defined as presence of delusions or hallucinations, as defined in the SCID psychosis module. Current clinical mood states of depressed, manic, mixed, or hypomanic states and of euthymic or subsyndromal states was based on standard STEP-BD procedures that used a clinical monitoring form (CMF) and application of DSM-IV criteria to all depressive and manic mood symptoms. All raters were trained in STEP-BD sessions in application of the CMF clinical mood status, and adequate interrater reliability was ascertained. Diagnoses were based on application of the SCID mood module and the MINI diagnostic interview using DSM-IV criteria, with all interviewers trained in STEP-BD sessions and adequate interrater reliability obtained.

Statistical analysis

For data analyses, medications were grouped as follows: lithium, standard anticonvulsants (valproate and carbamazepine), lithium plus anticonvulsants, novel anticonvulsants (lamotrigine, gabapentin, and topiramate), second-generation neuroleptics (clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and quetiapine), first-generation neuroleptics (haloperidol, perphenazine, and trifluoperazine), (serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline), tricyclic antidepressants (nortriptyline), other non-SRIs (bupropion, trazodone, mirtazapine, and nefazodone), and benzodiazepines (clonazepam and lorazepam). Novel agents included omega-3 fatty acids. Standard mood stabilizers were defined as lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine. Analyses were stratified by history of rapid cycling, psychosis, and diagnosis (bipolar I disorder compared with bipolar II disorder), as well as by clinical mood state at time of study entry (depressed; manic, mixed, or hypomanic; and euthymic or subsyndromal).

As recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (www.icmje.org), effect estimates were reported as proportional response rates with 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs), instead of comparisons based on p values. Because this study is descriptive, we did not engage in hypothesis-testing techniques. If reported, p values would be prone to multiple-comparison error, and because of the absence of a preplanned research protocol designed to test specific hypotheses, the use of such analyses based on p values would be inappropriate. In general, if the CIs exclude the null (risk ratio [RR]=1), then the analysis would be statistically significant in hypothesis-testing terms (p<.05). However, it is best to focus on the effect estimate (RR) and use the CIs as indicators of the precision of that effect estimate (narrower CIs indicate more precision).

Lastly, we use the term "neuroleptics," rather than the term "antipsychotics," throughout this report because the use of such agents in bipolar disorder is not limited to psychosis. Rather, all these agents share some risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (hence the utility of the term "neuroleptics"), with varying indications for treatment (often with no relevance to psychosis).

Results

In this sample of the first 500 patients in STEP-BD, 204 were male (40.8 percent) and 296 were female (59.2 percent). A total of 457 were white (91.4 percent), and 43 were nonwhite (8.6 percent). The mean±SD age was 41.5±12.9 years. A total of 368 (73.6 percent) had bipolar I disorder, 115 (23.0 percent) had bipolar II disorder, and 17 (3.4 percent) had bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. A total of 317 (63.4 percent) were currently euthymic or subsyndromal (did not meet DSM-IV criteria for current manic, mixed, or hypomanic or for major depressive episode), 123 (24.6 percent) met criteria for currently having a major depressive episode, and 59 (11.8 percent) met criteria for having a current manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode.

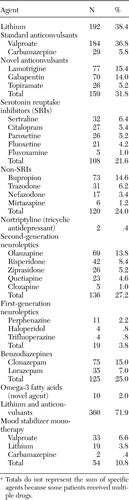

Medication distribution upon study entry is listed in Table 1 . The most frequently prescribed agents were lithium and valproate, which were about equally used. Only about one-tenth of patients received mood stabilizer monotherapy, most frequently with valproate. After lithium and valproate, the most commonly prescribed agents were lamotrigine, clonazepam, bupropion, and gabapentin, in descending order. The most commonly prescribed classes of agents were antidepressants (40.6 percent), novel anticonvulsants (31.8 percent), neuroleptics (31.4 percent), and benzodiazepines (25.0 percent). About 40 percent of the sample received antidepressants, the most commonly prescribed of which was bupropion (14.6 percent), which was prescribed more than two times as frequently as the next most common antidepressant. After bupropion, the SRIs sertraline, citalopram, paroxetine, and fluoxetine were prescribed with similar frequencies. The most commonly prescribed novel anticonvulsant was lamotrigine, followed by gabapentin and topiramate. The most commonly prescribed neuroleptic was olanzapine, followed by risperidone and ziprasidone. The most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine was clonazepam, followed by lorazepam.

|

a Totals do not represent the sum of specific agents because some patients received multiple drugs.

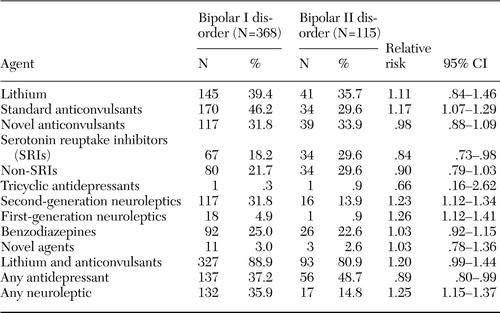

Medication use based on bipolar subtype is shown in Table 2 . It is notable that compared with patients with bipolar II disorder, those with bipolar I disorder were 17 percent more likely to receive standard anticonvulsants, 25 percent more likely to receive neuroleptics, and less likely to receive antidepressants.

|

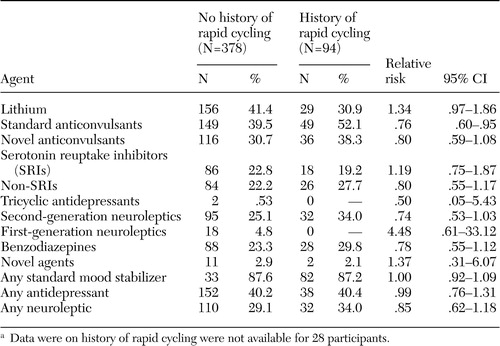

A total of 94 of 492 patients (19.1 percent; course data were not available for eight participants) experienced current rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Medication use based on a history of rapid cycling is shown in Table 3 . Patients with a history of rapid cycling were more likely than those without such a history to receive standard anticonvulsants.

|

a Data were on history of rapid cycling were not available for 28 participants.

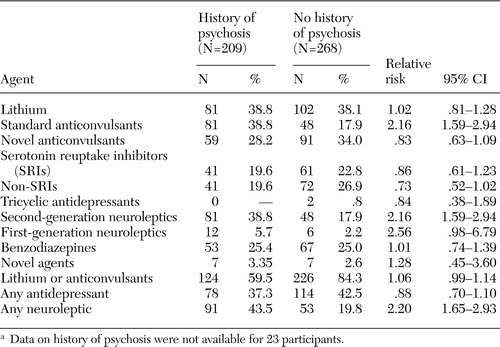

Compared with patients without a history of psychosis, those with such a history were more than two times as likely to be prescribed standard anticonvulsants or neuroleptic agents ( Table 4 ).

|

a Data on history of psychosis were not available for 23 participants.

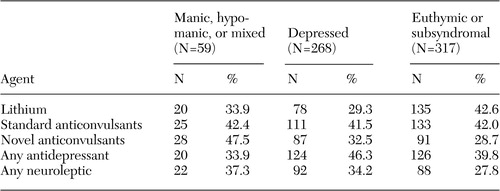

When patients were stratified by mood state, manic, hypomanic, or mixed patients were more likely than depressed or stable patients to receive novel anticonvulsants (risk ratio=1.47, 95 percent confidence interval=1.05 to 2.08). No notable difference was found in antidepressant or neuroleptic use between the acute and euthymic mood states ( Table 5 ).

|

Discussion

This study identified prescription patterns in a U.S. academic psychiatric setting of a large, well-characterized population of patients with bipolar disorder. The generalizability of these data, although the sample is much more representative of the general population than samples in clinical trials, is still limited to patients treated in academic centers who are willing and able to participate in a long-term follow-up study. The overall pattern of treatment seems similar to those found in previous studies in U.S. psychiatric settings ( 9 , 10 , 15 ). We found that 71.9 percent of patients received standard mood stabilizer treatment (lithium, divalproex, or carbamazepine), the largest portion of this sample. The next largest class used was antidepressants, which represented 40.6 percent of the total sample, followed by novel anticonvulsants and neuroleptic agents (31.8 and 31.4 percent, respectively). Benzodiazepines were also used by one-quarter of these patients. Mood stabilizer monotherapy was limited to 10.8 percent. The overall picture is one of polypharmacy, with extensive use of standard mood stabilizers and frequent use of antidepressants, novel anticonvulsants, and second-generation neuroleptic agents.

In other settings, such as the nonpsychiatric primary care setting, antidepressant use in bipolar disorder may be notably higher (72 percent) ( 11 ) or notably lower, as in Europe ( 7 ) and in some U.S. bipolar specialty academic settings ( 16 , 17 ), where long-term use is limited to 15 to 20 percent of patients. The use of antidepressants in bipolar disorder is controversial, with some evidence of short-term benefit during the acute major depressive episode ( 18 ) but with randomized evidence of lack of long-term preventive benefit in the maintenance phase of treatment ( 19 ). Although some observational studies suggest potential long-term benefits ( 17 ), randomized studies have been most consistent in showing a lack of long-term maintenance efficacy in prevention of new depressive episodes ( 19 ). However, course studies indicate that most patients with bipolar disorder spend about one-half of their lives depressed, compared with only about 10 percent of time in a manic or hypomanic state ( 20 ). Thus the common long-term use of antidepressants in this condition may reflect clinicians' awareness of a need for better treatments for the depressive symptoms of this illness.

Increasing use of novel anticonvulsants and second-generation neuroleptics suggests broader recognition of potential mood-stabilizing utility of these agents, as well as an increase in randomized clinical trials suggesting benefit with many of these agents ( 21 , 22 ). Previous studies of prescription patterns contained less data about the use of these newer treatments. Since this sample was initially assessed, most of the second-generation neuroleptics have received indications for various phases of bipolar disorder from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It is therefore likely that their use rates have increased further.

Prescription patterns in bipolar subtypes reflect the greater depressive morbidity of bipolar II disorder, with more antidepressant and less neuroleptic use. Although this approach is clinically rational, it is important to note the dearth of research on treatments for bipolar II disorder ( 23 ), which limits the evidence base for clinical decisions. Treatment patterns in psychotic bipolar disorder understandably reflected greater neuroleptic use, which is supported by a good deal of research on acute mania ( 24 ). Treatment patterns in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder were somewhat surprisingly similar to those in non-rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. It appears that a rapid-cycling course is a more severe and difficult-to-treat subtype of bipolar illness ( 25 ). No treatments have been proven effective in the treatment of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder in primary outcomes of randomized clinical trials ( 25 ). The only blind, controlled study showing efficacy with any intervention for rapid-cycling involved discontinuation of antidepressants ( 26 ). It is noteworthy that the rapid-cycling subtype did not seem to predict lower antidepressant use in the STEP-BD sample.

Given that this study is a cross-sectional analysis of the STEP-BD sample just before entry into this observational cohort study, inferences regarding longitudinal treatment must be made with caution. With that caveat, it appears that most agents used in the acute phases of bipolar disorder were similarly used in the maintenance phase of treatment. This observation is based on data in Table 5 , which demonstrate little differences between acute mood states (manic or mixed state and depressed state) and maintenance phases (euthymic or subsyndromal). If that observation is confirmed by longitudinal analyses from STEP-BD or other cohorts, then it will be even more important to identify in randomized studies that such a treatment approach is valid. Randomized studies supporting long-term maintenance of neuroleptic agents ( 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ) have been the subject of some methodological critiques ( 32 ). Randomized studies of long-term antidepressant maintenance after treatment for acute depression suggest lack of prophylactic benefit (compared with lithium) ( 19 ). Again, definitive inferences from this cross-sectional analysis are not warranted, but these observations suggest that future studies of prescription patterns should closely assess longitudinal prescribing practices across phases of bipolar illness.

Conclusions

In a large well-characterized cross-sectional analysis of prescription patterns in a U.S. psychiatric academic setting, patients with bipolar disorder were primarily treated with standard mood stabilizers, followed by moderate use of antidepressants, novel anticonvulsants, and second-generation neuroleptic agents. Results can be used to understand the current clinical standard of care, as well as to guide research studies toward areas where there is a relative absence of evidence to guide clinical practice. Studies of longitudinal prescribing patterns in bipolar disorder are also needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Research Career Award (MH-64189, Ghaemi). This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from NIMH under contract N01-MH-80001. This article was approved by the publication committee of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD).

1. Sachs GS: Bipolar mood disorder: practical strategies for acute and maintenance phase treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 16:32S-47S, 1996Google Scholar

2. Blanco C, Laje G, Olfson M, et al: Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1005-1010, 2002Google Scholar

3. Ghaemi SN: On defining "mood stabilizer." Bipolar Disorders 3:154-158, 2001Google Scholar

4. Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, Baraibar G, et al: Prescribing trends of antidepressants in bipolar depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:260-264, 1995Google Scholar

5. Ghaemi SN, Ko JY, Goodwin FK: "Cade's disease" and beyond: misdiagnosis, antidepressant use, and a proposed definition for bipolar spectrum disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 47:125-134, 2002Google Scholar

6. Ghaemi SN, Pope HG: Lack of insight in psychotic and affective disorders: a review of empirical studies. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 2:22-33, 1994Google Scholar

7. Frangou S, Raymont V, Bettany D: The Maudsley bipolar disorder project: a survey of psychotropic prescribing patterns in bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders 4:378-385, 2002Google Scholar

8. Lim PZ, Tunis SL, Edell WS, et al: Medication prescribing patterns for patients with bipolar I disorder in hospital settings: adherence to published practice guidelines. Bipolar Disorders 3:165-173, 2001Google Scholar

9. Levine J, Chengappa KN, Brar JS, et al: Psychotropic drug prescription patterns among patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders 2:120-130, 2000Google Scholar

10. Levine J, Chengappa KN, Brar JS, et al: Illness characteristics and their association with prescription patterns for bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders 3:41-49, 2001Google Scholar

11. Russo P, Smith MW, Dirani R, et al: Pharmacotherapy patterns in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 4:366-377, 2002Google Scholar

12. Ohayon MM, Lader MH: Use of psychotropic medication in the general population of France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:817-825, 2002Google Scholar

13. Hirschfeld RM, Calabrese JR, Weissman MM, et al: Screening for bipolar disorder in the community. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:53-59, 2003Google Scholar

14. Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al: Rationale, design, and methods of the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biological Psychiatry 53:1028-1042, 2003Google Scholar

15. Suppes T, Leverich GS, Keck PE, et al: The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network: II. demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 67:45-59, 2001Google Scholar

16. Ghaemi SN, Goodwin FK: Long-term naturalistic treatment of depressive symptoms in bipolar illness with divalproex vs lithium in the setting of minimal antidepressant use. Journal of Affective Disorders 65:281-287, 2001Google Scholar

17. Altshuler L, Suppes T, Black D, et al: Impact of antidepressant discontinuation after acute bipolar depression remission on rates of depressive relapse at 1-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1252-1262, 2003Google Scholar

18. Gijsman HJ, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, et al: Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1537-1547, 2004Google Scholar

19. Ghaemi SN, Lenox MS, Baldessarini RJ: Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:565-569, 2001Google Scholar

20. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:530-537, 2002Google Scholar

21. Yatham LN: Newer anticonvulsants in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65(suppl 10):28-35, 2004Google Scholar

22. Ketter TA, Wang PW, Nowakowska C, et al: New medication treatment options for bipolar disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica: Supplementum 422:18-33, 2004Google Scholar

23. Berk M, Dodd S: Bipolar II disorder: a review. Bipolar Disorders 7:11-21, 2005Google Scholar

24. Mensink GJ, Slooff CJ: Novel antipsychotics in bipolar and schizoaffective mania. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109:405-419, 2004Google Scholar

25. Tondo L, Hennen J, Baldessarini RJ: Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: effects of long-term treatments. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 108:4-14, 2003Google Scholar

26. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, et al: Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:179-184, 1988Google Scholar

27. Tohen M, Chengappa KN, Suppes T, et al: Relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder: 18-month comparison of olanzapine plus mood stabiliser v mood stabiliser alone. British Journal of Psychiatry 184:337-345, 2004Google Scholar

28. Tohen M, Greil W, Calabrese JR, et al: Olanzapine versus lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:1281-1290, 2005Google Scholar

29. Tohen M, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, et al: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine as maintenance therapy in patients with bipolar I disorder responding to acute treatment with olanzapine. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:247-256, 2006Google Scholar

30. Tohen M, Ketter TA, Zarate CA, et al: Olanzapine versus divalproex sodium for the treatment of acute mania and maintenance of remission: a 47-week study. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1263-1271, 2003Google Scholar

31. Marcus R, Carson W, McQuade R, et al: Long-term efficacy of aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 1-6, 2004Google Scholar

32. Ghaemi SN, Pardo TB, Hsu DJ: Strategies for preventing the recurrence of bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65(suppl 10):16-23, 2004Google Scholar