Cognitive Insight and Causal Attribution in the Development of Self-Stigma Among Individuals With Schizophrenia

Psychiatric stigma is recognized as a primary barrier to receiving adequate care and equal life opportunities for individuals living with mental illness ( 1 ). Stigma can cause psychological suffering for the affected individuals and families and compromises effectiveness in the provision of services. Despite evidence demonstrating the negative impact of stigma, less attention has been paid to understanding stigma from the perspective of the recipient. In this study we took a social-cognitive perspective in our exploration of self-stigma among individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia.

Self-stigma occurs when members of a subgroup immersed in the prejudicial attitudes of a dominant culture agree with these prejudices, apply the attitudes to themselves, and develop diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy as a result ( 2 ). From a social-cognitive perspective, the extent to which individuals are aware of their mental disorder and how they attribute the responsibility for their illness can affect the eventual acceptance of their illness and internalization of stigma. Although greater insight about mental illness has been shown to be related to better treatment outcomes ( 3 ), it can also imply greater chance of adopting the stigmatizing label and internalizing the stigma. In other words, individuals with cognitive insight about their mental illness may be prone to experience a greater level of self-stigma, whereas those with little insight may be more immune to self-stigma because of their unawareness of being stigmatized.

In addition to cognitive insight, illness attribution may be related to self-stigma among individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The link between perceived responsibility and stigma has been supported in the general public ( 4 ), with some harboring greater levels of hostility, blame, and contempt toward individuals with mental illness if the individuals are deemed personally responsible for causing the disorder ( 5 ). Similar linkage may be observed among individuals given a diagnosis of schizophrenia. If they consider themselves to be responsible for causing the illness and its associated impairments, they probably will develop a greater level of self-stigma. Nevertheless, such a relationship remains to be empirically investigated.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of cognitive insight and attribution of responsibility on self-stigma among individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia. By identifying the underlying factors that may contribute to self-stigma, more concerted efforts can be made in designing cognitive techniques to thwart its development and alleviate its adverse effects among stigmatized individuals.

Methods

Participants in this study consisted of 162 Chinese mental health service consumers (107 men and 55 women) from 15 community-based mental health service centers in Hong Kong. They had a broad DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, as determined by psychiatrists before individuals' intake at the respective service centers. The sample had a mean±SD age of 36±10.70 years (range of 18-64 years). Seventy-nine (49 percent) participants had at least a high school education. Age at onset was 35±10.38 years, and illness duration was 15.4±9.33 years. All of the participants were taking psychotropic medications at the time of the study.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained at the local institutional review board. Data were collected in group sessions from December 2004 to January 2005. Before data collection, the nature of the study was described to the consumers, and their informed consent was obtained. Each session included five to 18 consumers, who completed a self-report questionnaire with the help of research assistants.

Self-stigma was assessed by the 15-item self-stigma scale, which we developed and validated to measure the extent to which stigmatized individuals internalize public stigma and are affected emotionally, cognitively, and behaviorally. The scale was designed to be applicable to various stigmatized groups on the basis of diagnosis (such as people with mental illness or HIV/AIDS) or demographic characteristics (such as gay, lesbian, or bisexual individuals, or immigrants). The phrase "an individual recovering from mental illness" was inserted as the reference point for each item. Sample items for each dimension included "I am unhappy being [phrase]" (affective), "I conceal my identity as [phrase] from others" (behavioral), and "I am inferior to others because I am [phrase]" (cognitive). Participants rated their responses on a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from 1, strongly disagree, to 4, strongly agree. Factor analysis showed a one-factor structure to the scale, and the total mean score was used for analysis (Cronbach's α =.95).

The Beck Cognitive Insight Scale (BCIS) ( 6 ) was used to assess consumers' cognitive insight. The BCIS aims to measure the degree of self-reflectiveness in recognizing unusual experiences and self-certainty in interpretation of experiences. A composite index was calculated by subtracting the self-certainty subscale score (Cronbach's α =.71) from the self-reflectiveness subscale score (Cronbach's α =.82). Attribution of personal responsibility was assessed by items from the Causal Dimension Scale II ( 7 ) (Cronbach's α =.61). The Modified Colorado Symptom Index ( 8 ) was used to assess overall symptom severity of the consumers as symptomatology was found to be related to self-stigma ( 9 ) (Cronbach's α =.94). The medication side effects scale we developed consists of a list of 15 commonly experienced medical side effects of psychotropic medication and assesses the impact of the various side effects on consumers' daily living (Cronbach's α =.91).

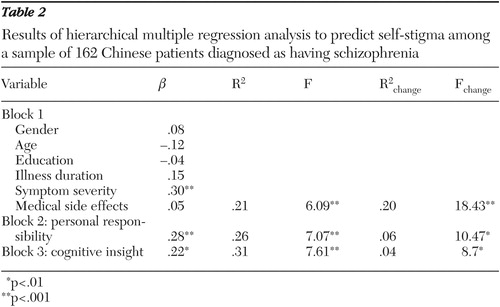

Hierarchical multiple-regression analysis was conducted to investigate the effects of cognitive insight and personal responsibility on self-stigma. Demographic factors, including gender, age, and education, along with illness-related factors, such as illness duration, symptom severity, and perceived medication side effects, were controlled for in the analysis.

Results

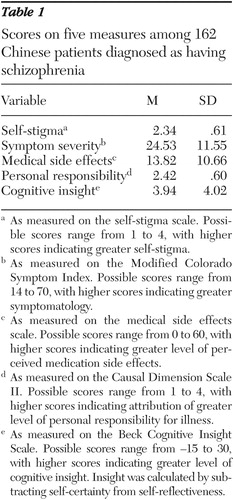

The overall regression model accounted for 31 percent of the variance in self-stigma (F=7.61, df=8 and 147, p<.001). Table 1 shows the mean scores on the measures, and Table 2 shows the results of the hierarchical regression analysis. None of the demographic factors were related to self-stigma. Among the illness-related factors, only symptom severity was significantly related to self-stigma, with a greater level of symptomatology related to a higher level of self-stigma (p<.001). When demographic and illness-related factors were accounted for in the model, personal responsibility and cognitive insight were found to add 6 and 4 percent of the variance in self-stigma, respectively (p<.01 for each relationship). On self-attribution, participants who attributed a greater level of personal responsibility to themselves for their illness reported a higher level of self-stigma. In regard to disease awareness, having a greater level of cognitive insight was significantly associated with experiencing a higher level of self-stigma.

|

|

Discussion

This study provides empirical support for the effects of cognitive insight and attribution on self-stigma among individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Mental health consumers who had greater cognitive insight into their illness and assigned greater responsibility to themselves for causing their illness experienced a greater level of self-stigma. Although future research into the mechanisms of this linkage is necessary, it is possible that insight is related to greater awareness of stigmatized status and perceived discrimination in society, which could lead to more internalization of stigma.

Such findings suggest that insight might be a double-edged sword for people with schizophrenia and complicate the understanding of the impact of insight on clinical outcomes. Insight can be an important asset for mental health consumers by enhancing their involvement in their treatment process ( 3 , 10 ). Increased insight allows individuals to be cognizant of the symptoms and deficits that are brought about by their illness and of the need to adhere to treatment for recovery. However, such insight also enables consumers to recognize the stigma that exists in society toward individuals who have a mental illness. Such recognition may lead to the internalization of stigma. In recent decades, insight has been conceptualized to be a multidimensional construct ( 3 ). Future studies should further decompose the construct and investigate its myriad effects on the recovery of individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Such work could explore medical outcomes, stigma, psychological well-being, and quality of life.

In this study, the relationship between insight and self-stigma was examined among mental health consumers diagnosed as having severe and persistent psychotic disorders. Given that the relationship between insight and self-stigma may vary depending on the level of cognitive functioning and the coping ability of the clients (with those who are more functional having better skills and abilities to cope with stigma), researchers should include clients with a range of cognitive functioning and severity of psychiatric conditions in future research to comprehensively examine the relationship between insight and stigma.

Another cognitive factor, attribution of responsibility, also was found to be positively related to self-stigma. Mental health consumers who assume personal responsibility for their illness are more likely to experience a greater level of self-blame, feel disabled, and have diminished self-worth. Educating consumers about overattribution of internal causality for their illness and training them to reattribute causality along multiple biological, psychosocial, and environmental lines could reduce their tendency of self-stigmatization.

Last, given that the study was conducted among Chinese participants and that culture may affect individuals' beliefs about mental illness, future research should explicitly address the issue of cultural influence on attributions and lay beliefs about mental illness and test it among culturally diverse groups.

Conclusions

This study was an initial attempt in understanding the effect of cognitive insight and attribution on self-stigma among individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Future studies should focus on testing the causal linkage from multiple dimensions of insight as well as different types of attribution in the development of self-stigma and should use a longitudinal design. In clinical practice, mental health professionals should give more attention to the issue of self-stigma and address it with consumers to reduce its adverse effects on recovery.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council Competititve Earmarked Research Grant (project no. CUHK-4145/04H). The authors sincerely thank the staff of the New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association for their assistance in data collection.

1. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

2. Corrigan PW, Watson, AC: The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 9:35-53, 2002Google Scholar

3. Schwartz RC: The relationship between insight, illness and treatment outcome in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly 69:1-22, 1998Google Scholar

4. Weiner B: On sin versus sickness: a theory of perceived responsibility and social motivation. American Psychologist 48:957-965, 1993Google Scholar

5. Corrigan PW: Mental health stigma as social attribution: implications for research methods and attitude change. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 7:48-67, 2000Google Scholar

6. Beck AT, Barunch E, Balter JM, et al: A new instrument for measuring insight: the Beck Cognitive Insight Scale. Schizophrenia Research 68:319-329, 2004Google Scholar

7. McAuley E, Duncan TE, Russell DW: Measuring causal attributions: the revised Causal Dimension Scale (CDSII). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 18:566-573, 1992Google Scholar

8. Conrad KJ, Yagelka JR, Matters MD, et al: Reliability and validity of a Modified Colorado Symptom Index in a national homeless sample. Mental Health Services Research 3:141-153, 2001Google Scholar

9. Yen CF, Chen CC, Lee Y, et al: Self-stigma and its correlates among outpatients with depressive disorders. Psychiatric Services 56:599-601, 2005Google Scholar

10. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:826-836, 1994Google Scholar