Special Section: A Memorial Tribute: The VADO Approach in Psychiatric Rehabilitation: A Randomized Controlled Trial

The results of a recent study of a representative sample of Italian psychiatric services have shown that only 35 percent of patients with schizophrenia who live with their own family are in a psychosocial rehabilitation program and that only 66 percent of these programs ask clients to define their personal goals ( 1 ). The most important likely causes are the psychodynamic orientation of many rehabilitation managers, the scarcity of mental health workers trained to teach social and work skills, and the absence of a structured framework to guide rehabilitation practice ( 2 ).

In 1998 the rehabilitation unit of the Fatebenefratelli Institute of Brescia (Italy), in collaboration with the Italian National Institute of Health and the Institute of Psychiatry of the University of Naples, published a short handbook for the planning and evaluation of rehabilitative interventions in psychiatric centers. The handbook was called VADO—Valutazione delle Abilità e Definizione degli Obiettivi (in English, Skills Assessment and Definition of Goals) ( 3 ). It was inspired by the Boston Rehabilitation Center's approach ( 4 ), which identifies patients' skill deficits and strengths and plans rehabilitative interventions strictly related to patients' goals.

The efficacy of the VADO approach was assessed with a multicenter partially randomized controlled study ( 5 ). However, the results must be interpreted with caution, because in three centers randomization was not performed and there was only a partial independence in the evaluation outcomes. Assessments using the Brief Psychiatric Rating scale (BPRS) and the Personal and Social Performance (PPS) were carried out by the VADO-trained rehabilitation workers. The assessments were checked by one independent research assistant at each center, who interviewed the rehabilitation workers after each assessment. The research assistants were instructed not to ask anything that could reveal the treatment received by the patients. In the few cases of disagreement between the research assistant and the rehabilitation workers, the rating was made by another independent research assistant. Thus an effort was made to check the validity of each assessment by independent research assistants, but bias was highly likely. To better assess the efficacy of the VADO approach, a new randomized controlled trial was subsequently planned. This trial and the one-year follow-up results are described in this article.

Methods

Procedure

This study was a multicenter, randomized controlled trial with a stratified design; assessors were blind to the patients' treatment condition. Fifty potentially eligible day treatment or residential rehabilitation facilities were selected according to a random sampling with stratification by population size, among all National Health Service day treatment or rehabilitation centers of five regions in Northern Italy. They were invited to take part in the study, and only nine centers agreed: one in the Brescia area (Lombardy region), two in the Piacenza area, one in Reggio Emilia and one in Rimini (Emilia Romagna region), two in Rovigo (Veneto region), one in Torino (Piemonte region), and one in Udine (Friuli-Venezia-Giulia region).

After staff in the participating centers were trained in the VADO method (see below for a description of the method), each center was asked to recruit at least ten patients over six months according to the following criteria: aged between 18 and 65 years; diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective or delusional disorder according to ICD-10 criteria; global functional score less than 70 on the PSP (see below for scoring information; this score corresponds to at least manifest difficulties in one key functioning area); no evidence of disabling physical diseases, psycho-organic syndromes, or mental retardation; stable medication regimen; no concurrent psychological or family interventions; and informed consent to participate. After baseline assessment, patients who had met these criteria were randomly assigned in each center to the VADO approach or to routine care. The randomization was performed by a central unit according to computer-generated random numbers, and the sample was stratified by medication (two strata: second- or first-generation antipsychotics). Institutional review boards of the centers approved the study.

Assessments

Basic demographic information and details of psychiatric history at the beginning of the trial and data on medication and inpatient episodes during the trial were recorded.

At the beginning of the trial (baseline), after six months, and after 12 months, personal and social functioning was assessed by the PSP scale and overall severity of symptoms was assessed by the Italian standardized BPRS Version 4.0 ( 6 ). The PSP is a modified validated version of the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) ( 7 ). As with the SOFAS scale, the PSP scale ranges from 100, excellent functioning, to 1, extremely severe impairment with risk for survival. The assessor is instructed to take into account four main areas: socially useful activities, including work and study; relationships; self-care; and disturbing and aggressive behaviors. Suicide risk is considered in the score only insofar as suicidal ruminations may interfere with social functioning. Scoring the PSP scale requires a brief training, which is outlined in the VADO handbook. The PSP can be easily scored by rehabilitation workers, including those with limited psychiatric experience ( 7 ).

Effort was made to blind three trained and experienced assessors to group allocation, instructing them to not ask anything that could reveal the approach received by the patients and instructing patients to not reveal details of their care. The treatment code was recorded in the assessment forms afterward in the central unit. Assessors were asked to guess the group allocation of each patient; the guesses were not significantly better than chance, suggesting that blinding was satisfactory. To rate the PSP, assessors interviewed the patient and the member of the staff not involved in the patient's treatment. The assessors then compared the answers and gave a consensus score.

Groups

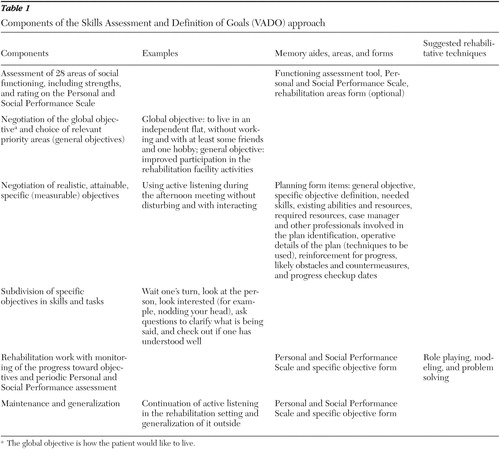

VADO approach. The aim of the VADO approach is to help the rehabilitative team to define and evaluate individual rehabilitative programs. It is mainly based on assessment of patient's disabilities and residual strengths, negotiation of realistic and measurable goals, subdivision of goals into elementary skills and tasks, and routine evaluation of progress toward the achievement of objectives ( Table 1 ).

|

The VADO handbook provides detailed instructions on how to assess the patient's disabilities or difficulties and residual strengths and how to negotiate the rehabilitation program with him or her; the handbook also include forms or tools, such as the functioning assessment tool (FA). The FA includes a number of questions that the rater must answer to conduct a semistructured interview to achieve a comprehensive and thorough assessment for 28 domains (see box on page 1781). Also included is the rehabilitation areas form (RAF). The 28 domains of the FA were listed on this form. For each domain, at the beginning of the rehabilitative intervention and whenever changes in planning intervention are introduced, the rehabilitation worker selects one of six possible alternatives: 0, absence of disabilities or problems; 1, presence of a problem: no planned intervention at present; 2, presence of a problem: planning intervention; 3, intervention in progress; 4, intervention concluded (after improvement); and not applicable: area not relevant (for example, domain number 14, if the patient does not have children). The handbook also provides the planning form (PF), which is used to develop a scheduled written plan for the attainment of a specific objective, and the specific objective form (SOF). The SOF includes the subdivision of specific objectives to relevant elementary tasks and skills, and it assesses how well and in which circumstances they are performed—that is, if they are performed autonomously or after verbal prompting and if they are performed in a sheltered rehabilitation program or in the real-life environment. Finally, the PSP scale is included in the handbook.

Domains assessed by the functioning assessment tool

1. Self-care

2. Self-care of clothes

3. Self-management of physical health

4. Self-management of psychological health

5. Housing

6. Area of residence

7. Care of personal environment

8. Job or socially useful activities

9. Amount of daily activities

10. Speed of movement

11. Participation in activities at residential and day treatment facilities

12. Participation to family activities

13. Intimate and sexual relationships

14. Child care

15. Time spent with people in social relationships

16. Friendships and support relationships

17. Anger control

18. Observance of cohabitation rules

19. Safety

20. Interests

21. General information

22. Need for education

23. Money management

24. Use of transportation

25. Telephone use

26. Purchases and payments

27. Coping with an emergency

28. Income, pension, and benefits

The main differences between VADO and the Boston Rehabilitation Center's approach ( 4 ) are the following. First, in the VADO approach, the rehabilitative work begins before the global objective is defined (for example, toward improvement in self-sufficiency) and the global objective is not considered to be permanent (for example, where the patient would like to live in two or three years and what he or she would like to do). Instead, the global objective may be modified while the patient improves his or her skills and self-confidence. Second, the VADO approach includes the PSP scale, as a measure for comparing different patients at baseline and during rehabilitation. Third, the VADO approach places a higher level of importance on subdividing objectives into elementary skills and tasks. Finally, the VADO approach has a more structured assessment of the progress toward achieving the objectives.

The VADO handbook suggests dividing complex goals into specific measurable objectives to be dealt with in sequence. The VADO approach does not describe rehabilitation techniques in detail and it does not require any specific rehabilitation techniques, although it recommends modeling and role playing. The rehabilitation workers involved in the VADO implementation were invited to continue using their rehabilitation techniques within the VADO structure.

Routine approach. The comparison rehabilitation approach was routine management. Most centers had personalized rehabilitation programs, and all centers offered a variety of common activities with rehabilitative potentials—for example, group discussion, reading and discussing newspaper stories, art therapy, excursions, and supported holidays.

Training in the VADO approach

Before beginning the study, at least two staff members from each center (one physician and one rehabilitation worker) attended a 32-hour training course on the VADO approach. The course lasts for eight hours a day for four days. The course is based on the small-group methodology, with extensive role playing and case discussion. Participants were shown videotapes of interviews with patients and were asked to score the cases on the PSP scale and to complete the RAF forms independently and then to discuss inconsistencies in their ratings. Participants discussed the individual cases, which were summarized in vignettes, and set objectives for each case. Only a cursory description of the most promising rehabilitation techniques was provided to participants.

After the course, participants attended a common supervision session one day per month for six months to discuss problems and doubts about the clinical management of patients. The session was at the Psychiatry Rehabilitation Unit, Fatebenefratelli Hospitalization and Care Scientific Institute. The session was a group session that focused on the patients treated with the VADO approach. Private sessions that focused on specific problems were available for individuals upon request. The session was conducted by the same professionals who were trained and experienced in the VADO method and conducted the VADO training.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS 12.0. PSP and BPRS total scores were tested for differences between groups by means of Student's t test, after homoscedasticity was assessed. Differences in the proportions of clinically improved patients in the two groups (VADO and routine care) and at the two times (baseline and 12 months) were examined with chi square tests. Clinical improvement was defined as an increase of at least 10 points on the PSP or a decrease of at least 20 percent on BPRS total score.

The definition of "minimal important clinical difference" as a difference of 10 points on the PSP score was decided on the basis of a recent further PSP validation study ( 8 ). The validation study used pooled data from two prospective, multicenter clinical antipsychotic trials and compared PSP scores with scores on the Clinical Global Impressions Scale ( 9 ) and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ( 10 ).

Results

Patient characteristics

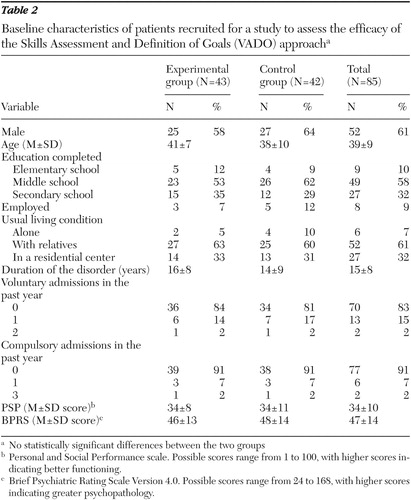

In the six months after the VADO training, the nine centers were able to recruit 85 patients who met entry criteria after the full assessment. Of these, 43 were randomly assigned to the experimental group and 42 were randomly assigned to the control group. As shown in Table 2 , most patients were middle aged and male and had limited education. Most were unemployed and living with relatives and had a long duration of illness. There were no clinical or sociodemographic differences between groups at baseline.

|

Setting and achievement of rehabilitation goals

Among the 43 patients in the intervention group, 144 specific objectives were planned, of which 108 (75 percent) were fully achieved (autonomous performance of all relevant skills or tasks). Planned specific goals involved the following domains of functioning: job or socially useful activities (31 of 42 goals were achieved), personal environment care (27 of 36 goals were achieved), friendly and supportive relationships (18 of 29 goals were achieved), self-care (19 of 22 goals were achieved), and participation in activities in residential and day treatment facilities (12 of 15 goals were achieved). Unfortunately, the objectives of the control group were not available because no modification in data recording was introduced.

Patient discharges and drop-outs

No patients were discharged from the rehabilitation programs in the first six months after random assignment. Two patients were hospitalized, one from the experimental group for alcohol abuse and one from the control group for a cardiac condition. The patient from the experimental group was considered to have dropped out. Consequently, at six months the study included 84 patients, 43 in the experimental and 41 in the control group. In the following six months, in the experimental group, a patient was transferred to another facility and another was hospitalized for a cardiac condition. In the control group, one patient was discharged and did not complete the 12-month assessment, and three other patients, all from day centers, dropped out. Consequently, the one-year assessment included 78 patients (93 percent of the original sample): 41 in the experimental group and 37 in the control group.

Efficacy

At baseline, average PSP scores in the experimental group and in the control group were 33.9±8.1 and 34.0±11.2, respectively. At six months, the score improved markedly in the experimental group (40.8±10.9), whereas minimal change was observed in the control group (35.3±11.6); the difference between groups was significant (an increase of 6.9 points compared with an increase of 1.3 points; t=2.21, df=81, p<.05). At 12 months, the same trend was observed; the scores continued to improve for both groups (a change in score between baseline and 12 months of 12.0 points compared with 3.5 points), and the difference in change scores was both statistically and clinically significant (t=2.99, df=75, p<.01).

By using the criterion of clinical improvement as an increase of at least 10 points on the PSP score, patients allocated to the VADO approach showed greater clinical improvement. At six months, 14 of the 43 patients (33 percent) in the experimental group showed clinical improvement compared with six of the 41 patients (15 percent) in the control group ( χ2 =3.72, df=1, p=.05). At 12 months, 21 of the 41 patients (51 percent) in the experimental group and six of 37 patients (16 percent) in the control group showed improvement ( χ2 =10.53, df=1, p=.001).

At baseline, average BPRS scores in the experimental group and in the control group were 46.0±13.4 and 47.7±14.3, respectively. At six months, the score improved more than 10 percent in the experimental group (40.1± 12.3) and less than 5 percent in the control group (45.9±14.7), and the difference between the groups was significant (t=-1.97, df=80, p=.05). At 12 months, no further improvement in either group was observed (42.4±10.4 in the experimental group and 47.1± 13.5 in the control group). At 12 months, ten of the 41 patients (24 percent) in the experimental group and seven of the 37 patients (19 percent) in the control group showed clinical improvement (a decrease of 20 percent or more on the total BPRS score). No clinically significant worsening was observed.

Discussion

Patients who received rehabilitation according to the VADO approach showed greater and lasting improvement in personal and social functioning than patients who received the routine approach. Neither approach was associated with stable significant improvement in psychopathology, though there was a slight tendency to greater improvement in the VADO group. The latter result was somewhat expected because patients were already in a good state of partial or full remission from florid symptoms. In a previous study ( 5 ), an improvement in positive symptoms was observed with the VADO approach; however, improvement was seen in only the two centers that were able to include disease self-management objectives among rehabilitation goals. It is possible that a significant ingredient of the VADO approach is the opportunity for empowered decision making. The VADO approach promotes the active involvement of patients in decisions about their individual objectives and care, resulting in greater control over their life situation and likely better functioning.

This study has several strengths: random, effective blind ratings; standardized measures; and low drop-out rates. Moreover, it evaluated the efficacy of a structured rehabilitation approach in clinical practice in ordinary centers, an approach that consumes few professional and financial resources and has a brief training period. This study shows that multicenter pragmatic trials of rehabilitation interventions are feasible, though difficult, even when they take place in centers with limited resources and an environment with little interest in participating (of the 50 centers invited to take part in the study, only nine accepted). On the other hand, the optimal size of the study was not estimated a priori, and the follow-up period, though better than most, should be extended. No attempts were made to control for the prescription of drugs; however, it is unlikely that the results are attributable to different medications, because patients were stratified according to the type of antipsychotic drug received. Another limitation is that the study samples were relatively small.

It is worth noting that no patients in the experimental group were judged to be ready for discharge during the one-year study period. This may reflect problems with the service organizations rather than a weakness in the VADO approach. In most areas, discharges are difficult, reflecting the lack of family involvement and the lack of available supported housing programs. As reported in a recent nationwide Italian study on the state of Italian psychiatric residential facilities ( 11 ), although 32 percent of the residents were younger than 40 years, discharge rates were extremely low.

Conclusions

We want to stress that mental health workers too rarely inquire about patients' wishes and objectives. Attention is paid more to the present condition or to the past one. The VADO approach compels workers to discuss the future with patients and to negotiate realistic but challenging objectives with them and to monitor their achievements. Because of these objectives, the VADO approach may be considered a useful instrument in psychiatric care. This study shows that the VADO approach is effective, even though professional techniques are not optimal (that is, specific rehabilitation techniques and treatment used in the approach are not recognized as being evidence-based practices).

Acknowledgments

Invaluable assistance in data gathering and project implementation was provided by the following staff members: Enrico Zanalda, M.D., Raffaello Roberti, M.D., Stefano Mistura, M.D., Emanuele Toniolo, M.D., Angelo Fioritti, M.D., Giovanni Foresti, M.D., Andrea Materzanini, M.D., Cesare Dainelli, M.D., Sergio Rizzon, M.D., Giovanna Barazzoni, M.D., Lorenzo Barina, M.D., Gianpietro Ferrari M.D., Riccardo Sabatelli, M.D., Corrado Cappa, M.D., Marisa Cavazzini, M.D., Tiziana Gon, M.D., Antonella Ferrari, D.Sc., Chiara Ossola, D.Sc., Monica Rabassi, D.Sc., Roberta Ferrari, D.Sc., Anna Maria Barbero, D.Sc., Enrica Loda, D.P.R.T., Luciana Rossi, D.P.R.T., Paola Manfredini, D.P.R.T., Marina Tosi, D.P.R.T., Flavia Aldi, D.P.R.T., Bice Scalori, D.P.R.T., Claudia Medici, D.P.R.T., Angela Fanti, D.P.R.T., Linda Raffaelli, D.P.R.T., Cosetta Canini, D.P.R.T., Emanuela Maresi, D.P.R.T., Federica Sordi, D.P.R.T., and Roberto Battaglia D.P.R.T.,. In particular, the authors also thank Marco Danesi, D.Sc., and Elena Bertocchi, D.Sc., for their collaboration in training and assessing activities.

1. Magliano L, Malangone C, Guarneri M, et al: The condition of families with schizophrenia in Italy: burden, social network, and professional support [in Italian]. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 10:96-106, 2001Google Scholar

2. Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179-182, 2001Google Scholar

3. Morosini P, Magliano L, Brambilla L (eds): VADO: Skills Assessment and Definition of Goals [in Italian]. Trento, Edizioni Erickson, 1998Google Scholar

4. Anthony WA, Cohen MR, Farkas MD (eds): Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Boston, Boston University, 1990Google Scholar

5. Pioli R, Vittorielli M, Gigantesco A, et al: Outcome assessment of the VADO approach in psychiatric rehabilitation: a partially randomised multicentric trial. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health 2:5, 2006Google Scholar

6. Roncone R, Ventura J, Impallomeni M, et al: Reliability of an Italian standardized and expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS 4.0) in raters with high vs low clinical experience. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:229-236, 1999Google Scholar

7. Morosini P, Magliano L, Brambilla L, et al: Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 101:323-329, 2000Google Scholar

8. Gagnon D, Adriaenssen I, Nasrallah H, et al: Reliability, validity and sensitivity to change of the Personal and Social Performance scale (PSP) in patients with stable schizophrenia. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Toronto, May 20-25, 2006Google Scholar

9. Guy W: Clinical Global Impressions, in ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

10. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261-276, 1987Google Scholar

11. De Girolamo G, Picardi A, Micciolo R, et al: Residential care in Italy: national survey of non-hospital facilities. British Journal of Psychiatry 181:220-225, 2002Google Scholar