Special Section: A Memorial Tribute: Care of Patients With the Most Severe and Persistent Mental Illness in an Area Without a Psychiatric Hospital

With deinstitutionalization of psychiatric care, the issue of patients with the most severe and persistent mental illness, requiring long-term, highly supervised care, remains a difficult one ( 1 , 2 ) and requires the establishment of prevalence data ( 2 ). As community-based care develops and long-stay wards disappear from psychiatric hospitals ( 3 ), facilities providing treatment and rehabilitation in a protected setting over a period of years may help difficult-to-place individuals move to less supervised settings ( 4 ). How many beds are required for people with high supervision, treatment, and rehabilitation needs? Given the high cost of such facilities, the question has important clinical and financial repercussions. The answer emerges from both "real-life" situations in best-practice areas and benchmarks proposed by experts ( 5 , 6 ).

Two decades ago in Massachusetts, Gudeman and Shore ( 7 ) estimated that 15 persons per 100,000 in the population could not be cared for in community programs available in their areas and, because of a lack of long-term-care beds, remained indefinitely in acute care facilities. They divided this heterogeneous cohort into five groups. Group 1 comprised elderly individuals diagnosed as having dementia and severe behavior problems, such as assault, screaming, and fire setting (three persons per 100,000). Group 2 comprised individuals with mental retardation who had concomitant psychiatric illnesses and violent behavior (three per 100,000). Group 3 comprised persons with brain damage, poor impulse control, and violent behavior (1.5 per 100,000). Group 4 included patients with schizophrenia who were an unremitting danger to themselves or to others (2.5 per 100,000). Group 5 comprised patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia complicated by socially unacceptable behaviors that made them vulnerable to exploitation (five per 100,000).

Gudeman and Shore were among the first to advocate small, specialized care facilities for each subgroup. The count of long-term psychiatric beds for such individuals in Massachusetts appears to be slightly higher (22 beds per 100,000 population) than forecast ( 8 ).

In England, Trieman and Leff ( 9 ), in the context of a large study on psychiatric hospital closures around London, identified a group of patients who appeared difficult to relocate in community settings, given various problematic behaviors. Others noted the same phenomenon ( 10 , 11 ). Case mix generally includes a majority of patients with diagnoses of schizophrenia, with sizeable minorities having affective disorders, an undefined variety of organic brain syndromes, or mental retardation. These patients have many difficult behaviors: physical and verbal violence, self-harm or suicidal tendencies, wandering, fire setting, inappropriate sexual behavior, incontinence, stealing, urinating or defecating in public, polydipsia, disrobing, shouting, and wandering ( 9 , 10 , 11 ). Trieman and Leff estimated the prevalence at ten to 11 per 100,000 in the population. This number fell in the lower bracket of the benchmark suggested by Wing and associates ( 6 ), with a range of ten to 40 or even 70 per 100,000, with higher needs in disadvantaged urban areas.

Lesage and associates ( 5 ), in an urban, working-class area (Montreal) endowed with a regional psychiatric hospital, surveyed all patients aged 18 to 65 either hospitalized in long-term care or living in supervised residential facilities. Assessing individual care needs, they estimated the need for narrowly supervised long-term beds to be 20 per 100,000 in the population. The actual count was 34 public long-term-care beds per 100,000.

There is a need for more real-life reports in various jurisdictions, especially nonurban areas with well-established mental health care. It is important to include all relevant patients, including those who are homeless, in jail, or in nursing homes, and to account for potential diversions of patients outside the catchment area. We report here the results of a cross-sectional survey conducted in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, Canada (a semiurban, semirural catchment area of 291,359 people), in the fall of 2002. The survey was embedded within a broader case study. Because the area had never had a psychiatric hospital or long-term psychiatric beds and relied exclusively on acute care psychiatric beds and various small community facilities, our intention was to determine how the area was handling the needs of its most severely ill patients. Survey objectives were to identify, within the catchment area, all patients with severe mental illness in need of a long-term, intense level of care; describe clinical and behavioral characteristics; and identify current residential arrangements.

Methods

The survey targeted all patients aged 18 to 65 either living and cared for in the catchment area between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2002, or originating from the area but cared for outside the area, who had medical documentation of a severe mental illness for at least two years and long-standing, severe behavioral problems requiring close supervision and thus incompatible with living in the community or in a minimally supervised facility. We excluded patients whose sole diagnosis was antisocial personality disorder, substance abuse, paraphilia, or mental retardation without any associated psychotic illness; patients with criminal behavior not associated with a psychotic illness; and patients experiencing dementia. The criteria thus narrowed the population to groups 4 and 5 described by Gudeman and Shore ( 7 ) and possibly included some in group 2.

To find these patients and assess the adequacy of the care system handling their needs, we conducted a broad inquiry along the lines of case study research ( 12 , 13 ). The design of the study was based on a model constructed from the articles of various authors on the possible untoward consequences of deinstitutionalization ( 1 , 2 , 7 , 14 , 15 , 16 ). This model suggests that if care for the most severely ill patients was inadequate or insufficient, the study would find various forms of evidence of this: high use of acute care beds for long-term stays, drift toward homelessness and incarceration, shunting of patients to out-of-area institutions, and administrative wrangling regarding the care of these patients. We first examined those possibilities by conducting 21 interviews with all pertinent informants from the regional health board, hospital mental health services, mental retardation services, public guardianship services, homeless shelters, the local jail, and community residential facilities.

We obtained from the regional health board access to administrative records of "difficult-to-place" patients. Hypothesizing that many of these patients would have been judged unable to care for themselves, we asked the public guardianship board to identify likely patients within its caseload and obtained permission to review medical records. To document inappropriately long stays in acute care, we examined records of all patients who had been admitted for more than six months within a year, between the years 1997 and 2002, and surveyed patients currently admitted at the time of the study. We sought evidence of out-of-catchment transfers through key informants and through provincial hospitalization databases. All relevant authorities agreed to cooperate for the study. The validity of case study research is contingent on efforts to verify data through multiple data sources, thus the search for redundancy ( 12 , 13 ).

In all facilities targeted as possibly housing the study population (including acute care wards, the local jail, community residences, and homeless shelters), staff were asked to identify patients within their caseloads who likely met the criteria. They provided basic information for each patient—date of birth, sex, diagnosis, known durations of illness and of residence in the institution—and agreed to complete the Riverview Psychiatric Inventory (RPI). A brief and jargon-free 36-item behavioral scale designed for completion by nursing staff and other care providers, the RPI provides rapid assessment of a pertinent repertoire of behavioral difficulties and symptoms of psychiatric inpatients. Its administration requires little or no training. Each item is scored on a 5-point scale (from 1, no problem, to 5, severe problem). Interrater reliability is high (coefficient=.89). The scale appears to validly discriminate poorly functioning patients from higher functioning, less ill ones ( 17 ). Medical records were also examined whenever possible by proxy consent.

Data were collected for 175 likely patients. After data collection, the two authors (one a senior researcher on the needs of patients with long-term mental illness) ( 5 , 18 , 19 , 20 ) examined the information available and, after discussion, reached an agreement on which of the 175 met the inclusion criteria. Using the same process, we further subdivided patients into two levels. Level 1 was for very severe and persistent behavioral difficulties necessitating close, 24-hour supervision and possibly a locked facility. Level 2 indicated severe behavioral difficulties, albeit less intense than in level 1, requiring 24-hour supervision, in particular assistance with basic activities, such as grooming and feeding, but with a clinical state compatible with an open-door facility.

The design was approved by the relevant institutional research ethics committees. Authorizations to examine medical records were obtained from all relevant authorities, and informed consent was waived.

Results

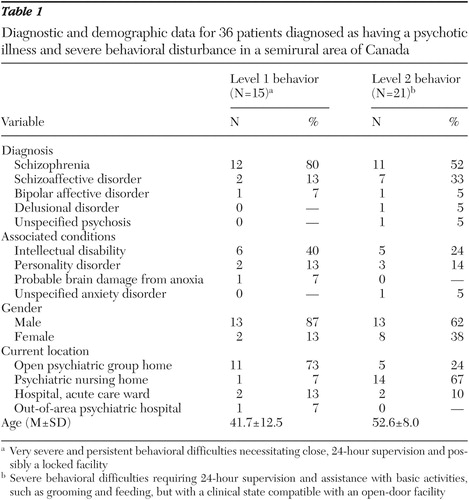

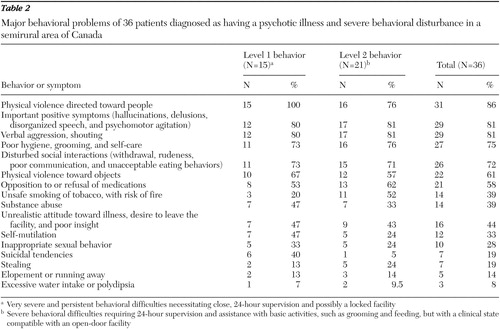

Thirty-six patients met the study criteria (prevalence of 12.4 per 100,000 in the population). All were Caucasian, and a large majority were of French-Canadian background. Fifteen were classified as level 1 (prevalence of five per 100,000) and 21 as level 2 (7.2 per 100,000). Table 1 summarizes demographic and diagnostic data of these patients. Comorbidity of mental illness and developmental disability was common. The total RPI score was a mean±SD of 3.97±.40 (95 percent confidence interval [CI]= 3.19-4.75) for level 1 patients and 3.53±.58 (CI=2.39-4.67) for level 2 patients. The maximum RPI score is 5, indicating severe disability and many severe problem behaviors. By comparison, the group most ill in the original validation study, where patients had been admitted to an aggression management program in a secure environment because of danger to self or others, had a mean score of 2.69±.86 (CI=1.00- 4.38) ( 17 ). Table 2 provides a list of the most common behavioral difficulties manifested by this cohort. To construct this table, only behaviors or symptoms rated as marked or severe on the RPI were included. Most patients displayed several problematic behaviors.

|

|

Of the 36 patients, only four (prevalence of 1.4 per 100 000) were currently in an acute care psychiatric ward. They had been there for many months, and sometimes years, because of a forensic component (deemed not responsible for criminal behaviors and still considered a risk to the public) or because community resources had been unable to care for them because of recurring violence. Most patients were identified in one of two community resources: a 60-bed, open psychiatric nursing home located in a quaint lakeside, New England-like village, with staff available 24 hours per day, and a 19-bed, open, private but publicly funded psychiatric group home in a somewhat remote rural location, also with staff available 24 hours per day. The relative isolation of this latter facility appeared to act as a barrier against elopement and substance abuse. We found it interesting that despite the high level of problematic behaviors, neither facility has locked wards or isolation rooms. Violence toward caregivers is reported as rare despite a high potential for it. Close, compassionate supervision and attention to early signs of emotional escalation appear to explain this situation.

Only one patient was found to have been transferred to a psychiatric hospital outside the catchment area because of serious behavioral problems, which confirmed the key informants' unanimous opinion of the great rarity of such transfers. Approximately once a year, patients are transferred to a provincial forensic psychiatric hospital, generally for at most a few months, and returned to the area. No patients were found to be currently homeless. In a fairly close-knit community, the disturbing behaviors displayed by this most severely ill group generally bring these individuals to the attention of the police or mental health services. However, some of the patients identified had had transient periods of homelessness in the past. One downtown mental health halfway house has specialized in caring for difficult-to-engage younger patients with severe mental illness and psychosis who have comorbid diagnoses and problems with the law. In our assessment none currently residing there were considered in need of higher levels of care.

No patients meeting the criteria were found in the local jail. A few patients diagnosed as having psychotic illnesses were currently serving sentences but did not display the unrelenting, severe disorganization of the study cohort. We did find evidence that a small group of patients, generally those with multiple comorbid conditions (schizophrenia, antisocial behaviors, substance abuse, or brain damage), tended to be repeatedly incarcerated and neglected by mental health services, pointing to the need for greater collaboration between correctional and health services; their needs could possibly be met by an intensive clinical case management team (or assertive community treatment).

Discussion

The study was conducted in a semirural catchment area of Canada that has been operating with a community psychiatric care system for more than three decades with no psychiatric hospital backup. The only psychiatric beds available are acute care, general hospital beds. Our thorough investigation of the area turned up 36 persistently and severely ill psychotic patients aged 18 to 65 requiring closely supervised residential settings (12.4 per 100,000 inhabitants). These individuals showed ongoing, severe psychotic symptoms, aggressive and socially embarrassing behaviors, suicidal tendencies, and poor daily living skills that are incompatible with independent living or residing with community support. We identified two streams of patients differentiated by the severity of aggressive and dangerous behaviors, similar to groups 4 and 5 in Gudeman and Shore's classification ( 7 ). The residential settings in this Canadian public managed-care system were institutional to some extent (nursing home wards) and represented a retreat (a somewhat remote, rural group home that bars access to drugs and alcohol) but were dissimilar from locked and coercive long-stay wards of former psychiatric hospitals. Concerns may be raised, however, about the extent of slow-stream rehabilitation in these facilities.

The prevalence figure is higher than Gudeman and Shore's ( 7 ) 1984 Massachusetts forecast of 7.5 per 100,000 if we include only groups 4 and 5. However, this forecast did not pan out; the actual figure of 22 per 100,000 in Massachusetts is higher than in the catchment area we studied ( 8 ). This may be a result of the higher needs in urban areas, where psychosis rates have been found to be higher ( 21 , 22 , 23 ). Disadvantaged, ethnically diverse urban areas, in contrast to more homogeneous semiurban regions, may show a three- or fourfold increase in relative needs for psychiatric services ( 23 ). Indeed, the estimated need for such long-term-care facilities for people with severe mental illness in an urban catchment area of Quebec, well endowed with supervised residential facilities and community psychiatric care and intensive home treatment, was 20 per 100,000, with an additional need for nursing home-type facilities of 20 per 100,000 ( 5 ). This latter type of facility plays a major role in the catchment area under study. Within this framework of varying needs depending on community type, we believe our results can be generalized. Somewhat similar studies of small-community alternatives for functioning without a psychiatric hospital have been reported in Italy ( 18 ), England ( 4 , 24 ), the United States ( 25 ), and Canada ( 26 ).

Study limitations are considered with regard to case identification. Our thorough investigation of facilities inside and outside the catchment area, through diverse databases and key informants from all relevant sectors, is unlikely to have missed anyone in this rather small region. However, when comparing our study with others, there may be reason to believe that the other studies underestimated their situation and forecast lower needs by omitting some settings from their surveys. Case identification was based not solely on residential setting (for example, not all nursing home residents aged 18 to 65 and diagnosed as having schizophrenia were considered) but on adjudication by the two investigators. Identification remains, in the end, a clinical judgment. However, several factors limited the risk of idiosyncratic judgments: our long clinical and research experience in showing the reliability and validity of such judgments on service needs ( 20 , 27 ), our systematic inquiry, and our use of a standardized instrument (the RPI) ( 17 )—which clearly showed cohort characteristics to be similar to those of "hard to place" long-stay inpatients ( 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 )—limited the risk of idiosyncratic judgments.

The cross-sectional nature of the study is a limitation. A longitudinal study with multiple measuring points could have identified possible fluctuations over time of the target population.

To establish diagnosis, we relied on information available in the charts or reported by caregivers and clinicians, and the clinical judgment of the first author, an experienced psychiatrist. With such methods, misclassification remains possible, with underestimation perhaps more likely because of insufficient information to confirm diagnoses. A formal diagnostic assessment of every potential patient would have meant obtaining direct consent from the patients themselves, a difficult endeavor with this disorganized patient population, which would have run the risk of missing cases in a study where counting everyone was a central goal. To ensure diagnostic clarity, we excluded elderly patients as well as those with mental retardation, brain injury, or dementia syndromes as the main diagnosis (groups 1-3 of Gudeman and Shore [7]). Their needs must be taken into account in any sensible planning of facilities to accommodate patients with severe behavioral problems.

Conclusions

What are the implications for planning for severely mentally ill patients? First, as suggested by the Health Evidence Network review ( 3 ) on the evidence for community-based care, it is possible to operate without a backup psychiatric hospital. However, in addition to acute care beds, assertive community treatment teams, supervised residential settings, and supported housing, such care networks also must provide highly supervised, community-based long-term residential services for a small number of patients with severe mental illness. The need for such services is in the range of ten to 40 beds per 100,000 inhabitants (or even 70 per 100,000), depending on the socioeconomic, urban versus rural, cultural, and historical characteristics of the area. An average in a province, state, or country might be 25 per 100,000 inhabitants ( 6 ). Facilities that can offer intensive treatment and rehabilitation, with security for staff and patients in a homelike environment, likely represent best practices ( 24 , 26 ).

Second, providing care to this small group of highly disturbed individuals must not overshadow the needs of the larger number of patients with severe mental illness found in various settings in the community who can benefit from community mental health care teams, optimal treatment and rehabilitation, intensive home care, or less supervised residential settings. In this study, a few patients were in jail or in a revolving-door situation and deemed to be at risk of eventually needing long-term, high-supervision residential care with successive loss of opportunities and hope.

Third, any facility providing long-term residential asylum should also provide ongoing treatment and rehabilitative efforts, in order to allow the individual to graduate to less supervised settings that provide more autonomy and freedom and thus improved quality of life. Continuous involvement of community mental health care teams, rather than discharge of accountability for this group of patients, is required to avoid segregation in the community.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mado Reid, Liane Savard, Josee Ellyson, and all the informants and collaborators.

1. Lamb HR, Bachrach LL: Some perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatric Services 52:1039-1045, 2001Google Scholar

2. Lamb HR, Shaner R: When there are almost no state hospital beds left. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:973-976, 1993Google Scholar

3. Tansella M, Thornicroft G: What are the arguments for community-based mental health care? Geneva, World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe's Health Evidence Network, 2003. Available at www.who.dk/hen/Syntheses/mentalhealth/200308221Google Scholar

4. Trieman N, Leff J: Long-term outcome of long-stay psychiatric in-patients considered unsuitable to live in the community: TAPS Project 44. British Journal of Psychiatry 181:428-432, 2002Google Scholar

5. Lesage A, Gélinas D, Robitaille D, et al: Towards benchmarks for tertiary care for adults with severe and persistent mental disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 48:485-492, 2003Google Scholar

6. Wing JK, Brewin CR, Thornicroft G: Defining mental health needs, in Measuring Mental Health Needs, 2nd ed. Edited by Thornicroft G. London, Gaskell, 2001Google Scholar

7. Gudeman J, Shore M: Beyond deinstitutionalization: a new class of facilities for the mentally ill. New England Journal of Medicine 311:832-836, 1984Google Scholar

8. Childs E, Preston R: Inpatient study report for the general court. Boston Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Department of Mental Health, 2004Google Scholar

9. Trieman N, Leff J: Difficult to place patients in a psychiatric hospital closure programme: the TAPS Project 24. Psychological Medicine 26:765-774, 1996Google Scholar

10. Fisher W, Simon M, Geller J, et al: Case mix in the "downsizing" state hospital. Psychiatric Services 47:255-262, 1996Google Scholar

11. Bigelow D, Cutler D, Moore L, et al: Characteristics of state hospital patients who are hard to place. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:181-185, 1988Google Scholar

12. Keen F, Packwood T: Qualitative research: case study evaluation. British Medical Journal 311:444-446, 1995Google Scholar

13. Yin R: Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1994Google Scholar

14. Jones K, Poletti A: Understanding the Italian experience. British Journal of Psychiatry 146:341-347, 1985Google Scholar

15. Jones K, Poletti A: The Italian transformation of the asylum: a commentary and review. International Journal of Mental Health 14:195-212, 1985Google Scholar

16. Jones K, Poletti A: The "Italian experience" reconsidered. British Journal of Psychiatry 148:144-150, 1986Google Scholar

17. Haley G, Iverson G, Moreau M: Development of the Riverview Psychiatric Inventory. Psychiatric Quarterly 73:249-256, 2002Google Scholar

18. Lesage AD, Tansella M: Comprehensive community care without long-stay beds in mental hospitals: trends emerging from an Italian good practice area. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 38:187-194, 1993Google Scholar

19. Brewin CR, Wing JK, Mangen SP, et al: Needs for care among the long-term mentally ill: a report from the Camberwell High Contact Survey. Psychological Medicine 18:457-468, 1988Google Scholar

20. Lesage AD, Morissette R, Fortier L, et al: Downsizing psychiatric hospitals:needs for care and services of current and discharged long-stay inpatients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 45:526-532, 2000Google Scholar

21. Marcelis M, Navarro-Mateu F, Murray R, et al: Urbanization and psychosis: a study of 1942-1978 birth cohorts in the Netherlands. Psychological Medicine 28:871-879, 1998Google Scholar

22. Sundquist K, Frank G, Sundquist J: Urbanisation and incidence of psychosis and depression: follow-up study of 4.4 million women and men in Sweden. British Journal of Psychiatry 184:293-298, 2004Google Scholar

23. Smith P, Sheldon TA, Martin S: An index of need for psychiatric services based on in-patient utilisation. British Journal of Psychiatry 169:308-316, 1996Google Scholar

24. Leff J, Szmidla A: Evaluation of a special rehabilitation programme for patients who are difficult to place. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37:532-536, 2002Google Scholar

25. Okin R: Testing the limits of deinstitutionalization. Psychiatric Services 46:569-574, 1995Google Scholar

26. Health and Welfare Canada: Seven Oaks Project, Victoria, British Columbia, in Best Practices in Mental Health Reform Phase II—Situational Analysis. Ottawa, Health and Welfare Canada, 1997Google Scholar

27. Van Haaster I, Lesage AD, Cyr M, et al: Further reliability and validity studies of a procedure to assess the needs for care of the chronically mentally ill. Psychological Medicine 24:215-222, 1994Google Scholar