Gender- and Trauma-Related Predictors of Use of Mental Health Treatment Services Among Primary Care Patients

Large-scale epidemiological studies consistently show that women are more likely than men to use mental health treatment services ( 1 , 2 ). Other associations with increased treatment use consistently found among community samples include previous exposure to traumatic events (such as sexual or physical assault) ( 1 ) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ( 3 , 4 ). However, only two studies have investigated predictors of use of mental health treatment among primary care patients, and they revealed an increased likelihood of service use among women, people of middle age (ages 40-49), people with higher education levels ( 5 ), and people who have been sexually or physically assaulted ( 6 ).

This study examined associations with lifetime and recent mental health treatment use among primary care patients in a prospective survey. We chose to focus on some of the variables consistently associated with treatment use across studies, including gender, trauma history, and probable PTSD diagnosis. Although other variables, such as education level, marital status, insurance status, age, and race, are conceptually related to treatment use ( 7 ), they can create mixed, often nonsignificant results and thus are not examined here. We did, however, explore attitudes toward mental health treatment (such as perceived credibility, value, and acceptance), an important but understudied variable in examining treatment use associations ( 7 ). We hypothesized that across lifetime and recent treatment utilization analyses, increased likelihood and intensity of use would be associated with female gender and more positive attitudes toward treatment. We also hypothesized that greater frequency of traumatic events (especially those related to crime) and diagnosis of probable PTSD would further increase likelihood and intensity of use of mental health services, above gender and treatment attitudes.

PTSD's high comorbidity with major depressive disorder could confound the relationship between PTSD and use of mental health care services. Yet this comorbidity is not solely accounted for by overlap of shared symptoms. Studies demonstrate that PTSD adds significant variance in predicting service use, even after controlling for other disorders, such as major depression ( 8 ).

Methods

Participants were 194 primary care patients (138 women and 55 men, with one not indicating gender) aged 18 and older who met appointments at one of two clinics affiliated with a state university medical school in the midwestern United States. Recruitment occurred in 2005, with institutional review board approval. Age of participants ranged from 18 to 85 years (M±SD of 45.55±16.95). Their education ranged from eight to 20 years and averaged 13.89±2.42 years. Annual income was less than $25,000 for 56 participants (29 percent), and was $25,000 to $34,999 for 35 participants (18 percent), $35,000 to $49,999 for 44 participants (23 percent), and $50,000 or higher for 51 participants (26 percent). Of the sample, 104 participants (54 percent) worked full-time, 22 (11 percent) worked part-time, and 66 (34 percent) were unemployed or retired. Most participants were Caucasian (186 participants, or 96 percent), with only 12 participants (6 percent) who were Hispanic, two (1 percent) who were African American, and none who were Asian. Of the sample, 124 participants (64 percent) were married, and 31 (16 percent) were single.

Over various days, 243 patients came to the clinic for appointments. On consecutive days, while patients waited in waiting rooms, research assistants invited patients to participate in the study. Patients were offered $10 in compensation, and 194 agreed to participate (80 percent response rate). After providing informed consent, participants were presented paper-and-pencil surveys in the fixed order described below.

A demographic survey queried for gender, age, education level, employment and relationship status, annual income, and race and ethnicity.

The Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire (SLESQ) ( 9 ) is a self-report measure to assess previous exposure to 13 DSM-IV PTSD criterion A events. Test-retest reliability and convergent validity are adequate (kappa values of .73, and .64, respectively) ( 9 ). We modified the yes-no event scaling, added queries about event frequency, and summed across violent-crime events and non-crime-related traumatic events, as distinguished in the literature ( 10 ).

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale-Self Report (PSS) is a 17-item DSM-IV -based PTSD measure that queries about symptom frequency and provides a 4-point Likert scale for responses ( 11 ). Internal consistency ranges from .65 to .71, with test-retest reliability between .66 and .77. The PSS has a correlation with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale of .87, with diagnostic sensitivity of .88 and specificity of .96 ( 11 ). Participants endorsing at least one traumatic event completed the PSS on the basis of their most distressing or only stressful event. Probable PTSD diagnoses, albeit based solely on self-report, were determined by DSM-IV PTSD symptom criteria. A symptom was counted as present if its rating was equal to or greater than 1 (or "once a week or less"). We also assigned "no PTSD diagnosis" to those with no history of trauma.

The Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale- Short Form (ATSPPH) is a 4-point Likert-scaled self-report survey ( 12 ). It is a ten-item measure of current attitudes toward seeking mental health treatment. Internal consistency ranges from .77 to .84 ( 12 ; Elhai JD, Schweinle W, Anderson SM, unpublished paper, 2006), with a one-month test-retest reliability of .80 ( 12 ). Validity is adequate, and service users tend to have higher scores ( 12 ; Elhai JD, Schweinle W, Anderson SM, unpublished paper, 2006). A total score is generated, and higher scores indicate more positive attitudes toward treatment.

The National Comorbidity Survey's Health and Service Utilization Assessment interview queries about previous use of mental health services across different health providers and clinics ( 13 ). We adapted this into a self-report survey, querying about lifetime and recent (six-month) time frames. Participants were asked whether they had ever sought mental health services from the listed providers (from a psychologist or general practitioner, for example) and about visit frequencies in the past six months. We computed lifetime and recent outpatient treatment variables by coding whether responses indicated previous use of mental health services. We calculated intensity of six-month treatment use by summing the number of visits to a provider.

Of 194 participants, eight were excluded for missing gender or service data, leaving 186. Remaining participants' rare missing continuous values were replaced with means. Total SLESQ frequency estimates showed substantial positive skewness, so we added a constant (value of 5) and logarithmically transformed scores, successfully normalizing distributions.

We assessed relationships between use of mental health care services and our predictor variables: gender, frequency of traumatic events from violent crime and other sources reported on the SLESQ (continuously scaled and log-transformed), probable diagnosis of PTSD reported on the PSS, and the ATSPPH total score (continuously scaled). Criterion variables included lifetime and recent service use and intensity of use in the past six months.

For univariate analyses, we used analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for associations between categorical-continuous variable pairs, chi square tests for categorical-categorical pairs, and Pearson correlations for continuous-continuous pairs. To assess the combined effects of predictor variables on lifetime use, we implemented logistic regression. Because of the preponderance of values of zero for six-month intensity of use, we used zero-inflated negative binomial regression designed for this situation and simultaneously examined associations with six-month nonuse of services and the continuum of the number of visits. Regression analyses were sequential. We first controlled for gender and treatment attitudes, exploring the possible incremental effect of trauma and PTSD.

Results

Of the 186 medical patients, 95 (51 percent) acknowledged and 91 (49 percent) denied having previously used mental health services. Regarding the use of services in the past six months, 45 patients (24 percent) acknowledged and 141 patients (76 percent) denied having used services (11.85±22.09 visits for six-month users, range 1-112). Lifetime use in primary care settings was endorsed by 51 patients (27 percent), and six-month use was endorsed by 25 (13 percent). Lifetime use in specialty care settings was endorsed by 87 patients (47 percent), and six-month use was endorsed by 36 patients (19 percent).

Corroborating epidemiological findings ( 10 ), 135 patients (73 percent) reported more than one previous trauma. The most prevalent events were the unexpected death of a loved one, reported by 69 of 186 patients (37 percent); suffering a life-threatening illness, reported by 47 patients (25 percent); and life-threatening accident, reported by 42 patients (23 percent). Before data transformation for frequency of trauma from violent crime, participants endorsed an average of 3.13±5.32 events, with 2.09±3.19 traumatic events from other sources, both substantially positively skewed. Among people reporting traumatic events, the most frequently endorsed distressing events, on which PSS ratings were made, included the unexpected death of a loved one (40 reported out of 135, or 30 percent), suffering a life-threatening illness (reported by 19, or 14 percent), and sexual assault (reported by 12, or 9 percent).

We assessed our predictor variables' associations with lifetime presence or absence of service use. Univariate ANOVAs revealed that lifetime use was significantly related to frequency of trauma associated with violent crime (F=44.51, df=1 and 184, p<.001; effect size η2 =.20, a large effect) and with other sources (F=4.10, df=1 and 184, p<.05; η2 =.02, a small effect), probable PTSD diagnosis χ2 =11.37, df=1, p=.001; r=.25, a near-medium effect), and ATSPPH scores (F=6.79, df=1 and 184, p=.01; η2 =.04, a small effect), with all associations in the expected directions. However, gender was not significantly related to use.

Logistic regression analyses indicated that gender and attitudes toward treatment significantly accounted for variance in lifetime service use χ2 =8.63, df=2, p<.05; Nagelkerke's R 2 =.06, a small effect). The trauma exposure and PTSD variables added incremental variance χ2 =44.41, df=3, p<.001; Nagelkerke's R 2change =.27, a large effect). Significant in the model were the ATSPPH scores, with each added point representing a 10 percent increased likelihood of use (Wald test=6.99, p<.01; B=.09, standard error of B=.03), and frequency of violent crime trauma (Wald test=22.12, p<.001; B=6.32, standard error of B=1.34).

Next, we assessed associations with recent service use. Univariate ANOVAs revealed that six-month service use (presence or absence) was significantly related to gender χ2 =4.02, df=1, p<.05; r=.15, small effect), frequency of trauma from violent crime (F=41.05, df=1 and 184, p<.001; η2 =.18, large effect), frequency of trauma from non-crime-related events (F=9.82, df=1 and 184, p<.01; η2 =.05, small effect), probable PTSD diagnosis χ2 =6.66, df=1, p=.01; r=.19, small effect), and ATSPPH scores (F=14.67, df=1 and 184, p<.001; η2 =.07, medium effect), with all associations in expected directions. Also, for intensity of six-month use among those attending at least one visit, univariate analyses demonstrated significant associations for gender (F=5.28, df=1 and 43, p<.05; η2 =.11, medium effect), frequency of violent crime trauma (r=.33, df=184, p<.05, medium effect), and frequency of non-crime-related trauma (r=.46, df=184, p=.001, large effect), with no significant associations for probable PTSD diagnosis or ATSPPH scores.

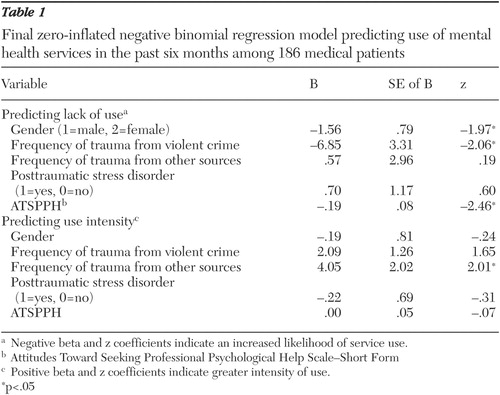

We assessed the model's predictive power in estimating six-month service use intensity ( Table 1 ). The overall zero-inflated negative binomial regression model for gender and treatment attitudes was significant χ2 =21.16, df=5, p<.001; maximum likelihood R 2 =.11, small effect), and trauma and PTSD variables added substantial variance χ2 =37.91, df=6, p<.001; maximum likelihood R 2change =.17, medium effect). The cumulative model's logistic component (predicting nonuse from use) was significant (likelihood ratio χ2 =20.68, df=5, p<.001), and the negative binomial component (predicting use intensity) was significant (likelihood ratio χ2 =21.45, df=5, p<.001). Male gender, decreased frequency of trauma from violent crime, and lower ATSPPH scores were positively associated with the lack of service use. Only frequency of non-crime-related trauma was associated (positively) with intensity of using mental health care services.

|

We recomputed regression analyses, using data from only the participants with a trauma history, and included symptom severity variables for PTSD's symptom criterion B (reexperiencing), criterion C (avoidance and numbing), and criterion D (hyperarousal). In comparison with results presented above, the reanalyses yielded almost identical results, with no PTSD variables significant.

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that gender and attitudes toward mental health treatment were significantly associated with previous treatment use, but gender was related specifically only to recent use. Trauma exposure and PTSD variables added substantial additional variance.

We found that frequency of exposure to traumatic events was substantially associated with treatment use and predicted the presence of lifetime and recent use and intensity of recent use, which corroborated earlier work among general ( 1 ) and primary care ( 6 ) samples. Trauma from violent crime in particular was a potent predictor of treatment use across analyses, supporting previous research that found more detrimental emotional effects for violent than nonviolent crime trauma ( 10 ). However, our findings revealed one exception: non-crime-related trauma was a better predictor of intensity of recent use, perhaps because such trauma is more common than trauma from violent crime and thus better at discriminating subtle variations in intensity than actual use from nonuse. We emphasize that neither lifetime service use nor intensity of use was examined in previous studies. Furthermore, whereas prior studies examined only presence and absence of previous sexual and physical abuse as service predictors, we measured trauma exposure more comprehensively and on a frequency continuum. Thus this study contributes to the literature in concluding that more frequent exposure to violent crime and to other traumatic events appears related to a greater likelihood and intensity of service use.

We found that a PTSD diagnosis was related to lifetime and recent treatment use, which is consistent with research predicting recent use ( 3 ). However, effect sizes for PTSD were small, and PTSD was not predictive of use in regression models. In fact, trauma frequency was significant in all regression models, appearing more important than PTSD in predicting treatment use. It is possible that the small effects of PTSD were due to decreases in PTSD symptoms that resulted from the receipt of effective treatment. Alternatively, exposure to trauma may itself be more important than its PTSD-specific effects in driving service use among people who have experienced traumatic events.

We discovered that more positive attitudes toward treatment predicted the presence of lifetime and recent service use and intensity of recent use (but not in a regression model). Despite sound theoretical support for the effect of treatment attitudes on treatment use ( 7 ), there has been little empirical study on this topic. Nonetheless, this finding warrants further study and could represent an important means of assessment and intervention. That is, initially assessing treatment attitudes may prove helpful in clinical decision making by identifying patients at risk of nonadherence to treatment. For such patients, clinicians might avoid intensive treatment regimens that would be unwelcome and with which compliance may be unattainable. Furthermore, improving treatment attitudes might result in increased treatment use among those who need treatment. However, because our research was correlational, we cannot conclude that more positive treatment attitudes "caused" greater treatment use. Cognitive dissonance theory could account for mental health care users' positive attitudes toward treatment.

We confirmed previous research demonstrating positive associations between female gender and increased presence and intensity of recent treatment, but only in the recent-use regression model. Specifically, past research has found an increased presence of recent use among women from the general population ( 1 , 2 ) and primary care samples ( 5 ). However, we did not confirm the relationship between female gender and lifetime treatment use, perhaps because of low gender variability (female participants outnumbered men by 2.5 times), possible stigma among men in acknowledging recent mental health problems, or possible sample artifacts.

Despite this study's unique contribution to the mental health services literature, it was not without limitations. First, although standard in services research, self-reported use of health services tends to underestimate visit frequency recorded on medical charts ( 14 ). Second, our data were obtained from two midwestern primary care clinics where the clientele is largely Caucasian, and generalizability to primary care clinics in other geographical locations is not known. Third, because we recruited patients who came in for appointments, our sample may not be representative of all patients registered with the clinics and may overrepresent more frequent clinic visitors. Fourth, mental health care is often sought in primary care rather than secondary care settings, which is inconsistent with our findings. Finally, we did not use structured diagnostic interviews to confirm PTSD.

Conclusions

Across regression models, trauma and PTSD incrementally contributed to predictions of mental health care use among medical patients. Trauma exposure in particular demonstrated significant associations, and female gender and positive treatment attitudes were associated with use in univariate analyses and some regression models. Clinical implications include the suggestion that assessing treatment attitudes could assist in the identification of treatment nonadherers, who could in turn be offered less intensive treatment. Alternatively, educational interventions in primary and specialty mental health settings aimed at improving treatment attitudes could prove beneficial in increasing treatment access and adherence.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by a Research Catalyst Award to the first and second authors from the Office of Research and Graduate Education, University of South Dakota.

1. Sorenson SB, Siegel JM: Gender, ethnicity, and sexual assault: findings from a Los Angeles study. Journal of Social Issues 48:93-104, 1992Google Scholar

2. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629-640, 2005Google Scholar

3. Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, et al: The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:427-435, 1999Google Scholar

4. Jaycox LH, Marshall GN, Schell T: Use of mental health services by men injured through community violence. Psychiatric Services 55:415-420, 2004Google Scholar

5. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Durham ML: Predictors of outpatient mental health utilization by primary care patients in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:908-913, 1994Google Scholar

6. Walker EA, Unützer J, Rutter C, et al: Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:609-613, 1999Google Scholar

7. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1-10, 1995Google Scholar

8. Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Sengupta A, et al: PTSD and utilization of medical treatment services among male Vietnam veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:496-504, 2000Google Scholar

9. Goodman L, Corcoran C, Turner K, et al: Assessing traumatic event exposure: general issues and preliminary findings for the Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire. Journal of Traumatic Stress 11:521-542, 1998Google Scholar

10. Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, et al: Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61:984-991, 1993Google Scholar

11. Foa EB, Tolin DF: Comparison of the PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview version and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13:181-191, 2000Google Scholar

12. Fischer EH, Farina A: Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help: a shortened form and considerations for research. Journal of College Student Development 36:368-373, 1995Google Scholar

13. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115-123, 1999Google Scholar

14. Elhai JD, North TC, Frueh BC: Health service use predictors among trauma survivors: a critical review. Psychological Services 2:3-19, 2005Google Scholar