A Randomized Trial of a Brief HIV Risk Reduction Intervention for Men With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A six-session version of a longer, 15-session social skills intervention for reducing high-risk sexual behaviors among men with severe mental illness was assessed. METHODS: Ninety-two men were randomly assigned to the intervention or to a two-hour standard HIV educational session, and their sexual risk behaviors were assessed every six weeks for six months. RESULTS: Among the sexually active men (33 in the intervention group and 23 in the control group), a twofold reduction in sexual risk behaviors was found for the intervention group. This reduction was less than the threefold reduction seen for the original 15-session intervention and was not statically significant. CONCLUSIONS: Further study is required to determine the optimal balance between efficacy and feasibility of this intervention.

The spread of HIV among men and women with severe mental illness challenges researchers to develop effective risk reduction interventions for mental health programs (1,2). Such interventions must be both efficacious and feasible in these settings.

After extensive qualitative research, our group developed an ethnographically based social skills intervention entitled "Sex, Games and Videotapes" (SexG) for men with severe mental illness (3). Fifteen one-hour sessions are administered over eight weeks. The high dose allows for frequent repetition, and the long duration gives the men time to practice safer sexual behaviors. The intervention was tested in a randomized clinical trial and produced a significant, three-fold reduction in high-risk behaviors (3).

Because 15 sessions may be difficult to deliver in routine clinical settings, we designed a streamlined version, SexG-Brief. Like SexG, it is informed by cognitive-behavioral theory and social skills training and utilizes humor and interactive exercises to keep the men's attention. Dose reduction to six one-hour sessions was achieved by focusing on the highest-risk sexual behaviors—unprotected sex with casual partners—and by retaining exercises from the original intervention that contained key theory-based elements and elicited the most active response by participants as assessed by qualitative assessment of videotapes. We report here the six-month follow-up results of a randomized clinical trial of SexG-Brief. [Editor's note: SexG-Brief is described more fully in this month's Frontline Reports column on page 417.]

Methods

The trial was conducted in the psychiatric day program of a homeless shelter and in three transitional living communities for men with severe mental illness in New York City. The trial described here was closely modeled on our previous trial (3). Ninety-two men were randomly enrolled in seven consecutive waves from September 1995 to June 1996 to participate in the intervention or in a control group. They were predominantly African American (60 participants, or 65 percent) and Latino (19 participants, or 21 percent). The mean±SD age of the participants was 38±9.2 years (range, 25 to 45 years). All had one or more psychiatric hospitalizations, and their diagnoses included schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (66 participants, or 72 percent), major depressive disorder (nine participants, or 10 percent), and bipolar disorder (three participants, or 3 percent). Fourteen participants (15 percent) had no DSM-III-R axis I diagnosis. The range of diagnoses in this sample closely parallels that in our previous trial. Alcohol and drug dependence were common among participants; 16 participants (18 percent) had alcohol dependence only, 15 (16 percent) had drug dependence only, and 23 (25 percent) were dependent on both alcohol and drugs.

Fifty-six of the participants were sexually active in the six months before they entered the program, and 36 were not. As in our previous study, the sexually active men were the main focus of the intervention. Sexually inactive participants were included to assess the intervention's safety—that is, whether a sexually explicit intervention would stimulate risk behavior. The study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

SexG-Brief was designed to reduce the riskiest sexual behaviors—unprotected anal or vaginal sex with casual partners. The men attended two one-hour sessions a day (morning and afternoon) every other day for a total of six sessions. The control group attended one two-hour standard HIV educational session, which included instruction in condom use. The attendance of the control group participants was 100 percent. For the intervention, 28 men (56 percent) attended all six sessions, 16 (32 percent) attended four sessions, and six (12 percent) attended two sessions.

Randomization resulted in assignment of 50 participants to the experimental group (54 percent) and 42 to the control group (46 percent). Among the 56 sexually active men, 33 (59 percent) were randomly assigned to the intervention and 23 (41 percent) to the control group. The groups did not differ significantly on any demographic variable, psychiatric diagnosis, history of substance abuse, or duration of homelessness during the previous 12 months. No significant differences were found in risk behaviors between experimental and control groups at baseline as measured by average number of partners (male and female), types of partners (steady or casual), and condom use.

Baseline assessments included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R to establish psychiatric diagnoses and the Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule (SERBAS)-Adult Armory Version to assess sexual behaviors in the six months before enrollment. Both instruments have been tested for reliability in this population (4,5). During the six-month follow-up period, an instrument derived from the SERBAS was administered every six weeks to assess sexual behaviors and calculate sexual risk. For the entire study population, retention over six months was 95 percent (96 percent for the intervention group and 95 percent for the control group). Among the sexually active men, retention over six months was 93 percent (94 percent for the intervention group and 91 percent for the control group).

In keeping with our previous trial (3), we used a sexual risk index, the Vaginal Episode Equivalent (VEE), as the primary outcome measure (6). The VEE is weighted on the basis of statistical estimates of the relative risk of various sexual behaviors; it assigns 2.0, 1.0, and 0.1 VEE points for each unprotected anal, vaginal and oral episode, respectively. To calculate a man's cumulative VEE score, we added his VEE points for each episode of unprotected sex with casual partners (women or men) during the designated period.

The main analysis compared the sexually active men from the SexG-Brief group and the control group with respect to their mean VEE score at six months by using an independent t test. We performed an intention-to-treat analysis; the four men lost to follow-up were assigned the average outcome for the sample. As in our previous trial, a separate analysis was done for the men who were not sexually active.

Results

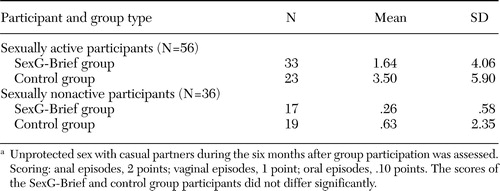

As shown in Table 1, the mean VEE score of the 56 sexually active men at six-month follow-up was twofold less in the SexG-Brief than in the control group (1.6 compared with 3.5), which was not a significant difference. Among the 36 men who were not sexually active at baseline, the trend was similar, although the variance was even higher (.26 compared with .63).

Discussion

The main finding of this trial was a twofold reduction in risk scores among sexually active men in the SexG-Brief group compared with the control group. The result was not statistically significant and might have been due to chance. However, it may reflect a true reduction in risk that the trial was underpowered to detect at the .05 level of significance. When considered within the context of the statistically significant findings from the original 15-session intervention, a reasonable inference is that the observed reduction in efficacy from threefold to twofold was a result of the decrease in the number of intervention sessions. Nonetheless, until an adequately powered trial can determine whether the twofold reduction in risk is reproducible with a higher degree of certainty, the efficacy of SexG-Brief remains unproven.

The second finding is that the men who were not sexually active at baseline were no more likely to initiate sexual activity after participating in SexG-Brief than the men who attended the educational control group. This result, consistent with our previous trial, suggests that, on average, participation in a sexual risk reduction intervention by men who are not sexually active is safe.

The main limitation of this trial is that it was underpowered. Several factors determined the sample size. Our team used the estimated effect size from our preliminary analysis of Sex-G for the power calculation for this study. In retrospect, that assumption underestimated the impact of a reduction in intervention dosage and duration. It is worth noting, however, that at the time the only published clinical trial of HIV risk reduction for people with serious mental illness reported positive findings with a total dose of six hours (7). A subsequent review of small-group interventions for women also suggested that six hours might be efficacious (8). Lacking the resources for a larger trial, and motivated by a desire to quickly develop an intervention that could be more widely used for this vulnerable population, we proceeded with the trial reported here.

An additional limitation is that the frequency and duration of the control group did not match those of the experimental condition. Thus, the observed difference between the two groups could be the result of nonspecific attention rather than the actual content of SexG-Brief.

The versions of the SERBAS used at baseline and follow-up differed in terms of the time interval covered, and we were therefore unable to calculate baseline VEE scores and change scores. The additional data would have more definitively established the comparability of the sexual risk behaviors of the two groups at baseline and enhanced our ability to interpret the primary outcome.

Conclusions

Several studies have now demonstrated that sexual risk behavior change is possible for those with chronic mental illness (3,9,10). It should be noted, however, that the samples of patients in these studies were diagnostically heterogeneous; in one sample (9) mood disorders predominated, whereas in another sample (10), as in our study, most participants had schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Differences in underlying psychiatric conditions and comorbid conditions, such as substance abuse, may have an impact on the dosage and the content needed for effective risk reduction.

Our group has now tested two social skills interventions for groups of men with primarily chronic psychotic disorders using varying intervention dosages and essentially identical methods for conducting the clinical trial as well as outcome variables and data analytic approaches. Our effort to make SexG more feasible and flexible for dissemination to treatment settings diminished but may not have eliminated its efficacy. The trial reported here represents a first step toward balancing efficacy and feasibility in order to achieve effective intervention in this population; a more adequately powered trial is required to definitively demonstrate its effectiveness.

Dr. Berkman and Dr. Susser are affiliated with the department of epidemiology of the Mailman School of Public Health, 722 W. 168th St., Room 1511, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail, ([email protected]). Dr. Cerwonka is with the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University and the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Alexandria, Louisiana. Dr. Sohler is with the department of epidemiology and social medicine of Albert Einstein College of Medicine in Bronx, New York.

|

Table 1. Scores on the Vaginal Episode Equivalent at six-month follow-up among men who participated in an HIV risk reduction intervention (SexG-Brief) or a control group, by whether they were sexually active at baselinea

a Unprotected sex with casual partners during the six months after group participation was assessed. Scoring: anal episodes, 2 points; vaginal episodes, 1 point; oral episodes, .10 points. The scores of the SexG-Brief and control group participants did not differ significantly.

1. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S: Prevalence of HIV infections among psychiatric patients in a New York City men's shelter. American Journal of Public Health 83:568–570,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kelly JA: HIV risk reduction interventions for persons with severe mental illness. Clinical Psychology Review 17:293–309,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Susser E, Valencia E, Berkman A, et al: Human immunodeficiency virus sexual risk reduction in homeless men with mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:266–272,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, et al: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): II. multi-site test-retest reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:630–636,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Sohler N, Colson PW, Meyer-Bahlburg HF, et al: Reliability of self-reports about sexual risk behavior for HIV among homeless men with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:814–816,2000Link, Google Scholar

6. Susser E, Desvarieux M, Wittkowski KM: Reporting sexual risk behavior for HIV: a practical risk index and a method for improving risk indices. American Journal of Public Health 88:671–674,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, et al: Use of a brief behavioral skills intervention to prevent HIV infection among chronic mentally ill adults. Psychiatric Services 46:275–280,1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Exner TM, Seal DW, Ehrhardt AA: A review of HIV interventions for at-risk women. AIDS and Behavior 1:93–124,1997Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, et al: Reducing HIV risk behavior among adults reserving outpatient psychiatric treatment: results from a randomized controlled trail. Journal of Consultative Clinical Psychology 72:252–268,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Otto-Salaj LL, Kelly JA, Stevenson LY, et al: Outcomes of a randomized small group HIV prevention intervention trial for people with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 37:123–144,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar