Spirituality and Religious Practices Among Outpatients With Schizophrenia and Their Clinicians

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Religious issues may be neglected by clinicians who are treating psychotic patients, even when religion constitutes an important means of coping. This study examined the spirituality and religious practices of outpatients with schizophrenia compared with their clinicians. Clinicians' knowledge of patients' religious involvement and spirituality was investigated. METHODS: The study sample included 100 patients of public psychiatric outpatient facilities in Geneva, Switzerland, with a diagnosis of nonaffective psychosis. Audiotaped interviews were conducted with use of a semistructured interview about spirituality and religious coping. The patients' clinicians (N=34) were asked about their own beliefs and religious activities as well as their patients' religious and clinical characteristics. RESULTS: Sixteen patients (16 percent) had positive psychotic symptoms reflecting aspects of their religious beliefs. A majority of the patients reported that religion was an important aspect of their lives, but only 36 percent of them had raised this issue with their clinicians. Fewer clinicians were religiously involved, and, in half the cases, their perceptions of patients' religious involvement were inaccurate. A few patients considered religious practice to be incompatible with treatment, and clinicians were seldom aware of such a conflict. CONCLUSIONS: Religion is an important issue for patients with schizophrenia, and it is often not related to the content of their delusions. Clinicians were commonly not aware of their patients' religious involvement, even if they reported feeling comfortable with such an issue.

Schizophrenia remains a debilitating, often chronic disease that can be associated with impairment in multiple domains of functioning (1). The concept of recovery (2) may be useful in caring for patients with schizophrenia, through its emphasis on personal achievement rather than symptom reduction. From this perspective, religion—defined in the broad sense as including both spirituality (concerned with the transcendent and addressing the ultimate questions about life's meaning) and religiosity (specific behavioral, social, doctrinal, and denominational characteristics)—can be helpful for patients whose social life and identity have been severely damaged by the course of the disease.

Indeed, some authors have pointed out that religious practices are common among psychiatric patients in Europe (3,4) and North America (5,6). Up until now, research on schizophrenia has examined mainly religious delusions and hallucinations with religious content, but religion as a coping mechanism has been the subject of growing interest (7). In clinical practice, clinicians may be reluctant to take this issue into consideration. Several factors may account for the neglect of religious issues in psychiatric practice: an underrepresentation of religiously inclined professionals in psychiatry, which has been noticed among both North American (8) and British psychiatrists (9); a lack of religious education for mental health professionals (8,10); and mental health professionals' tendency to pathologize the religious dimensions of life (10,11). The neglect of religious issues in psychiatry may also be linked to the rivalry between medical and religious professions that stems from the fact that both domains address the dilemma of human suffering (12,13).

The study reported here examined the extent to which religion helped outpatients with schizophrenia to cope with their illness. In addition, the importance of religion was evaluated among the patients' clinicians. The degree to which clinicians were aware of their patients' religious involvement and spirituality was investigated. The ease with which clinicians were able to discuss this topic was evaluated, as well as the potential clash between health care and religion, as described by patients. Finally, we evaluated clinicians' understanding of patients' views of this conflict. Our hypotheses were that religion is more important for patients who have chronic psychotic illness and less important for clinicians than in the general population and that patients' religious practices and spirituality are underestimated and neglected by clinicians.

Methods

Study design and procedure

One hundred patients, all followed in Geneva's four public psychiatric outpatient facilities, were included in the study. These clinics offer long-term treatment, primarily for patients with diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depressive disorder, and personality disorder. The multidisciplinary teams are composed of a first-line psychiatrist, who can be assisted by nurses or social workers, or both, if necessary. Patients receive supportive psychotherapy, somatic treatments, and rehabilitation as needed. Patients between 18 and 65 years of age who met ICD-10 (14) criteria for a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other nonaffective psychoses were included in the study. Patients were excluded if their clinical condition prevented them from participating in the interviews. Data collection took place between May 2003 and June 2004. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the University Hospital of Geneva. Patients participated in the study only after receiving detailed information about the study and signing a written consent document.

In each clinic, about 200 patients were eligible for this study. Clinicians at the four outpatient clinics were provided with information about the research. Psychiatrists were asked to solicit all successive eligible patients in their care to participate in the study. One of the authors (the second author) then met with patients to conduct audiotaped interviews. At that point, three patients refused to participate in the study. Demographic data were collected, and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (15) and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (16) were then administered. Psychosocial adaptation was evaluated with axis V of DSM-IV (17). Subjective quality of life was evaluated with a visual analogue scale.

No validated French-language questionnaires exist that survey religion and religious coping. We developed a semistructured interview adapted from several different scales or questionnaires—the Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness or Spirituality for Use in Health Research (18), the Religious Coping Index (19,20), and a questionnaire on spiritual and religious adjustment to life events (21). Our clinical interview with the patients explored, with 20 open questions, the spiritual and religious history of patients, their beliefs, their private and communal religious activities, the importance of religion in their daily lives, the importance of religion as a means of coping with their illness and its consequences, the synergy versus the incompatibility of religion with somatic and psychiatric care, and the patients' ease with speaking about religion. In addition to this interview, the salience of religiosity (that is, the frequency of religious activities and the subjective importance of religion in daily life), religious coping, and synergy with psychiatric care were quantified by a visual analogue scale with five anchored points. The duration of the interview was about 30 minutes. A test of this clinical interview in a sample of ten patients demonstrated its compatibility with different characteristics of the religious beliefs, practices, and coping methods encountered. Responses obtained by the interviewer of the 100-patient sample were compared with those from 15 additional interviews conducted by the third author to control for interviewer bias. The comparison of the two sets yielded equivalent distributions and patterns.

Clinicians were questioned about their religion. Clinicians were also asked about each patient's compliance, religion, religious coping with illness, and the synergy between religious practice and treatment. Clinicians were also questioned about the ease with which they discussed religion with patients. Two patients refused to allow their clinician be interviewed. One psychiatrist refused to be questioned about his religion. Consequently, data for 19 psychiatrists, 11 nurses, and five social workers were analyzed, providing descriptions of 98, 71, and 30 patients, respectively.

Comparisons between our sample and the general population were made on the basis of data from a sociologic survey conducted in 1999 (22), after authorization was obtained from that study's author. A random sample of 1,561 individuals living in Switzerland was contacted by telephone and questioned about religion and social relationships. In addition, 1,205 participants returned a written questionnaire about values and social relationships. Despite the methodologic differences between that study and ours, it was nevertheless possible to obtain some insight from a comparison between patients and clinicians and the general population.

Statistical analysis

An exploratory principal components analysis with rotation including three variables (the frequency of group religious practices, the importance of individual religious practices, and the subjective importance of religion in daily life) was used for patients and clinicians. Comparisons between clinicians and patients were made with nonparametric statistics: the chi square test and Wilcoxon's signed-rank test. Comparisons between clinicians were made with use of nonparametric statistics: the chi square test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. The number of patients treated by a clinician was independent of both patients' and clinicians' religious characteristics. Thus all data were used to compare clinicians' representations with their own religious characteristics and the religious characteristics of their patients with use of nonparametric statistics: the chi square test, the Kruskal-Wallis test, and Wilcoxon's signed-rank test.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study are summarized in Table 1. These characteristics are representative of those of the patients treated in these clinics. Forty, 25, 22, and 13 patients, respectively, were recruited in the four outpatient clinics.

The study psychiatrists were younger than the nurses and social workers (mean±SD ages of 35±6 years, 46±5 years, and 46±11 years, respectively). The gender distribution was equivalent across professions (41 percent male). No significant differences in spirituality and religious practices were found by profession, age, or gender.

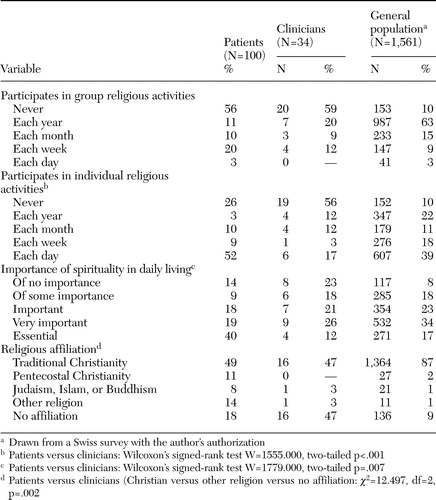

Religious practice and spirituality for patients, clinicians, and the general Swiss population (22) are described in Table 2. Most of the general population belonged to traditional Swiss Christian churches (Protestant or Catholic), whereas the study patients were more likely to mention Pentecostal churches, non-Christian religions, minority religious movements (for example, esoterism, spiritism, Christian Science, Scientology, or Ufology) or double religious affiliation (for example, both Muslim and Christian or both Buddhist and Christian). Seventeen percent of the clinicians claimed to be atheist, compared with only 5 percent of the general population. Patients were more involved and clinicians less involved than the general population in individual religious activities. Despite patients' extensive religious involvement, there was no significant difference between patients and clinicians in the extent of participation in religious activities.

The principal components analysis that examined the frequency of religious practices and the subjective importance of spirituality yielded a solution with two factors for patients. The first explained 61 percent of the variance and included individual religious practices with the subjective importance of spirituality, and the second explained 24 percent of the variance and included group religious practices. Thus group activities were weakly correlated with spirituality (Kendall's tau b=.27) and individual activities (Kendall's tau b=.30). Analyses of content showed that these weak correlations were related to psychopathology reflecting aspects of religious belief (16 patients), difficulties in social relationships (24 patients), rejection from religious communities (two patients), and participation in community religious activities without religious beliefs (two patients).

For the clinicians, the principal components analysis yielded a different solution from that of the patients, with one factor explaining 80 percent of the variance. Group activities were highly correlated with spirituality (Kendall's tau b=.65) and individual activities (Kendall's tau b=.72). According to this factor, clinicians were distributed across three groups: those who did not engage in religious practices and did not value spirituality (42 percent), those who did not engage in religious practices but valued spirituality (26 percent), and those who engaged in religious practices and valued spirituality (32 percent).

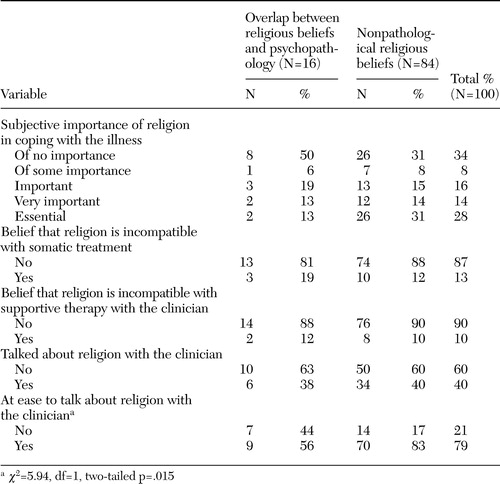

Because religion and psychopathology may overlap, we distinguished patients who had positive psychotic symptoms that reflected aspects of their religious beliefs (N=16) from the other patients (N=84). No differences were found between these two groups in religious affiliation, frequency of individual religious practices, and the importance of religion in daily living and coping. However, none of the patients whose symptoms reflected aspects of religious belief took part in community religious practices. Table 3 describes religious coping and synergy with psychiatric treatment. Patients whose symptoms reflected aspects of religious belief felt less at ease to speak about religion with their clinicians. For five of these seven patients, this was related to the fact that they feared being hospitalized if they talked about this topic.

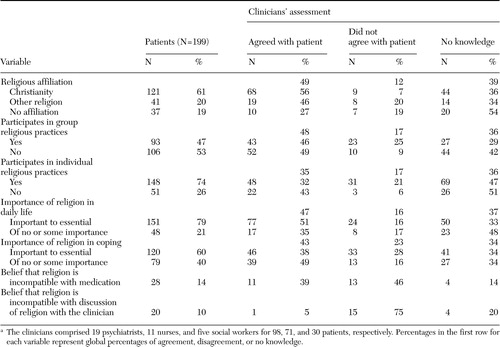

Clinicians' assessments of patients' religious characteristics are summarized in Table 4. Across the sample, clinicians tended to underestimate the importance of religion to their patients. Clinicians reported discussing religious issues with their patients in only 36 percent of cases, even though they claimed to feel at ease speaking about spirituality in 93 percent of cases. Only six clinicians (17 percent) reported feeling ill at ease with some of their patients. None of the clinicians initiated discussions of the topic themselves. Nineteen clinicians (54 percent) thought that they lacked skills in this domain (data not shown).

A minority of patients perceived a conflict between psychiatric care, medication, and spirituality, but for the patients who perceived these domains as being incompatible with discussions of religious issues, only one clinician was aware of the problem (Table 4). Clinicians' ease, frequency in discussing religion, and awareness of patients' religious beliefs were not linked to the content of patients' religious beliefs (that is, whether such beliefs reflected pathological or nonpathological thought processes).

Further analyses did not indicate any relationship between clinicians' age and gender and their knowledge of patients' religious beliefs and practices. Psychiatrists and nurses were significantly more aware of patients' religious characteristics than social workers.

For patients whose positive psychotic symptoms reflected their religious beliefs (16 percent), no relationship was found between the clinician's personal religion and the clinician's awareness of the patient's religion. For the other patients (84 percent), different relationships were elicited for psychiatrists and nurses. For the psychiatrists, no relationship was found between their personal religion and their awareness of their patients' religion, with the exception of religion as a way of coping with illness: psychiatrists who were more religiously involved were more sensitive to their patients' religious coping (W=1493.0, two-tailed p=.054).

Nurses' religion was inversely related to their knowledge of patients' religious affiliation (W=845.0, two-tailed p=.041), their representation of patients' ease of discussing religious issues (W=937.0, two-tailed p=.011), and their awareness of patients' beliefs about the compatibility of religion and medication (W=960.50, two-tailed p=.001) and between religion and supportive therapy (W=942.5, two-tailed p=.006).

Psychiatrists' religious involvement was highly and inversely related to their ease in discussing spirituality with patients who had pathological beliefs (Kendall's rank correlation=-.72, two-tailed p<.001) and moderately inversely related to their ease in discussing such matters with the other patients (Kendall's rank correlation=-.37, two-tailed p=.001). For nurses, no relationship was observed between their religiosity and their ease in discussing spirituality with patients.

Clinicians whose religious backgrounds were similar to those of their patients were not more aware of their patients' religion. Psychiatrists and nurses were more aware of patients' religious affiliation only for patients who reported frequent religious practices (W=1205.0, two-tailed p<.001 for psychiatrists and W=536.0, two-tailed p=.001 for nurses). However, for the other patients' religious characteristics, no statistical associations were found with psychiatrists' and nurses' knowledge of them.

Discussion

This study showed, as we expected, that religion was important for a majority of patients suffering from psychotic illness who were treated in the Geneva, Switzerland, area. Health professionals were less religiously involved than the patients they were treating. Patients were characterized by a high level of spirituality, which served as an important coping mechanism. These results are consistent with those of other studies carried out in Europe (3,4) and North America (5,6). Most patients engaged in religious activities alone; group activities were less common. In particular, principal components analysis showed that, for the patients, group activities were not related to spirituality or individual religious activities. This finding suggests that—as confirmed by the analysis of content—for some patients with schizophrenia, difficulties in relationships and social integration may also constitute a barrier to the fulfillment of spiritual needs.

These results can be compared with those for the general population of Switzerland, as reported in the study mentioned above (22). Although that survey was different from our research, it nevertheless made an interesting comparison possible and enabled us to conclude that patients with chronic psychosis may be more prone to religiosity than the general population. On the other hand, their clinicians reported the opposite trend, thus confirming other studies that reported an underrepresentation of religiously inclined professionals in psychiatry (8,9).

As we hypothesized, clinicians underestimated and often neglected patients' religious practices and spirituality. Psychiatrists, nurses, and social workers did not accurately describe the religious activities and spirituality of their patients: patients' spirituality and group religious practices were correctly identified in half the cases, whereas individual religious practices were identified only for one-third of the patients. Clinicians more accurately described the social dimensions of religion (affiliation and community practices) than the subjective ones, especially religion's relationship with the illness and with psychiatric care.

Some patients expressed the view that religion is incompatible with psychiatric care, but clinicians were rarely aware of this conflict. An analysis of the content of such views showed that some patients believed spirituality to be antagonistic to medication—some invested in spirituality in order to be healed from schizophrenia and refused medication, and others believed that medication hindered spirituality or had diabolic characteristics. Some patients believed that they should not talk about their spirituality, especially those whose religious beliefs overlapped with positive psychotic symptoms. This belief was due mostly to fear of being misunderstood and branded as religiously deluded, which would consequently lead to a risk of being involuntarily hospitalized.

Similar awareness of patients' religious characteristics was found for both psychiatrists and nurses, in both cases related to patients' involvement in religious communities. Clinicians who were more religiously involved did not describe their patients' spirituality and religious practices more accurately, possibly because they felt less at ease to talk about this topic, as indicated by their responses.

Despite these results, a precise explanation of why clinicians were unaware of their patients' religious practices and spirituality cannot be directly established on the basis of our data. A first—but self-evident—possibility is that clinicians broached this topic in only 36 percent of cases. This reluctance is apparently not an issue of feeling uncomfortable with the topic, given that clinicians reported feeling at ease speaking about religion in 93 percent of cases. Further investigation of clinicians' attitudes is necessary to clarify this apparently contradictory situation. It is likely that, in such a survey, clinicians tried to show themselves "at their best," an attitude that may have biased their answer to this question. In addition, a majority of the clinicians claimed a lack of skills in this domain, which led some of them to listen to their patients without going further in the subjective dimension of religion. Patients' attitudes may also play a role. Although a majority don't consider religion to be incompatible with psychiatric care, this topic seems difficult for some patients to share with others, either in religious or medical environments.

Our study had some limitations. Although the number of patients in the sample made it possible to report credible results, especially given that the patients were treated in four different outpatient clinics, the smaller number of clinicians casts doubt on the accuracy of the data for the clinician sample. In particular, the data for the social workers should be considered as exploratory given the small number of social workers. Similar studies should be repeated in larger geographic areas, given that, in order to have a sufficiently large sample, we needed to include almost all psychiatrists and nurses employed in public outpatient clinics in Geneva who worked with patients treated for chronic psychosis. Finally, religion's cultural aspect should be kept in mind, and our results should be considered in the particular context of this part of Switzerland. However, even though further studies may be needed on clinicians' representations of their patients' spirituality and religious practices, our results for both patients and clinicians are consistent with those of studies conducted in other countries.

Conclusions

This study showed that religion can be an important factor in coping with the chronic and devastating condition that schizophrenia often represents. During stabilization of the illness, few patients manifest religious beliefs that overlap with psychopathology. Our study showed that religion is largely ignored in supportive discussions that are designed to help patients find social support and achieve personal goals.

Dr. Huguelet, Ms. Mohr, and Dr. Borras are affiliated with the Secteur Eaux-Vives, Department of Psychiatry, University Hospitals of Geneva, Rue du 31-Décembre 36, 1207, Geneva, Switzerland (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Gillieron is with the faculty of psychology of the University of Geneva. Dr. Brandt is with the faculty of theology of Lausanne University in Lausanne, Switzerland.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 100 outpatients with schizophrenia who participated in a study of spirituality and religious practices in Geneva, Switzerland

|

Table 2. Spirituality and religious activities among outpatients with schizophrenia and clinicians and in the general population of Switzerland

|

Table 3. Religious coping and synergy with psychiatric treatment among outpatients with schizophrenia

|

Table 4. Clinicians' awareness of their patients' religious practices and spiritualitya

a The clinicians comprised 19 psychiatrists, 11 nurses, and five social workers for 98, 71, and 30 patients, respectively. Percentages in the first row for each variable represent global percentages of agreement, disagreement, or no knowledge.

1. Lalonde P, Grunberg F (eds): Psychiatrie Bio-psycho-sociale [Biopsychosocial Psychiatry]. Montréal, Gaëtan Morin, 1999Google Scholar

2. Andresen R, Oades L, Caputi P: The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 37:586–594,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Neeleman J, Lewis G: Religious identity and comfort beliefs in three groups of psychiatric patients and a group of medical controls. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 40:124–134,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kirov G, Kemp R, Kirov K, et al: Religious faith after psychotic illness. Psychopathology 31:234–245,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Tepper L, Rogers SA, Coleman EM, et al: The prevalence of religious coping among persons with persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:660–665,2001Link, Google Scholar

6. Kroll J, Sheehan W: Religious beliefs and practices among 52 psychiatric inpatients in Minnesota. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:67–72,1989Link, Google Scholar

7. Mohr S, Huguelet P: The relationship between schizophrenia and religion and its implications for care. Swiss Medical Weekly 134:369–376,2004Medline, Google Scholar

8. Shafranske EP: Religion and the Clinical Practice of Psychology. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1996Google Scholar

9. Neeleman J, King MB: Psychiatrists' religious attitudes in relation to their clinical practice: a survey of 231 psychiatrists. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 88:420–424,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lukoff D, Lu FG, Turner R: Cultural considerations in the assessment and treatment of religious and spiritual problems. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 18:467–485,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Crossley D: Religious experience within mental illness: opening the door on research. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:284–286,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sims A: The cure of souls: psychiatric dilemmas. International Review of Psychiatry 11:97–102,1999Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Roberts D: Transcending barriers between religion and psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:188,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. International Classification of Diseases, 10th ed. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1993Google Scholar

15. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. North Tonawanda, NY, Multi-Health Systems, 1992Google Scholar

16. CGI Clinical Global Impressions, in ECD-EU Assessment for Psychopharmacology. Edited by Guy U. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

17. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

18. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

19. Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, et al: Religious coping and depression among elderly, hospitalized medically ill men. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1693–1700,1992Link, Google Scholar

20. Koenig HG, Parkerson GR, Meador KG: Religion index for psychiatric research. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:885–886,1997Medline, Google Scholar

21. Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM: The many methods of religious coping: development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56:519–543,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Campiche RJ: Les deux visages de la religion. Fascination et désenchantement. [The Two Faces of Religion: Fascination and Disenchantment] Geneva, Labor et Fides, 2004Google Scholar