Representation of Asylum Seekers and Refugees Among Psychiatric Inpatients in London

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Refugees are at high risk of mental disorders but often complain about a lack of access to appropriate care. The purpose of this study was to assess the representation of refugees among psychiatric inpatients, given that it has been suggested that they use a disproportionate level of care compared with nonrefugees. METHODS: A census of all psychiatric inpatient units in London was used to determine the numbers of inpatients, the numbers of refugees, and measures of need, such as compulsory detention, duration of admission, need for interpreters, and whether inpatient status was appropriate. RESULTS: Of 2,955 psychiatric inpatients, 134 (4.5 percent) were refugees. Refugees' admission rates were similar to or lower than those of nonrefugees. Refugees were more likely to be inappropriately placed, to require interpreters, and to have more complex needs. CONCLUSION: The results of this study suggest that refugees are not overusing London's psychiatric inpatient units but have complex needs that challenge existing service providers.

The plight of refugees and asylum seekers has been of major importance since the 1951 Geneva Convention defined their status in legal terms, which highlighted their needs for asylum and care. Today, of 17 million refugees in the world, 4.2 million are located in Europe, and just under a million are in the United States (1). Refugees and asylum seekers usually settle in urban areas close to ports of entry (2,3).

Asylum seekers and refugees have a high risk of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and suicidal thinking as a consequence of war experiences, torture, political oppression, bereavement, separation from families, isolation from social support, and having fled their country (4,5,6). These risks, along with the complexity of social, cultural, legal, and political dilemmas encountered in the asylum process, lead service providers and policy makers to expect greater use of health services. Despite concerns about lack of access to health care (4), news media often report that refugees drain scarce health service resources (4,7). In reality, few data quantify refugees' use of health services (8).

In this study we compared the true extent of refugees' and nonrefugees' utilization of London psychiatric inpatient units as well as the complexity of their needs.

Methods

The survey consisted of a census of adult psychiatric inpatient facilities, including locked psychiatric intensive care units, and used established methods to assess the number of psychiatric inpatients at an aggregate level across a large number of centers (9). A newsletter was distributed to all key personnel in all adult acute inpatient services in London. The newsletter provided background information on the study, definitions of "refugee" and "asylum seeker" (the term "refugee" is used for both in this article), and the procedure for the survey. For the purposes of this study we included migrants whose legal status was uncertain as well as refugees as defined by the Geneva Convention.

We visited all 39 psychiatric hospital sites in all 33 London boroughs. Complete data were collected for 138 of 139 hospital wards. Ward managers completed a pro forma for a census point: midnight and midweek on a prespecified day for each hospital site. Researchers visited the ward twice, first to distribute and explain the questionnaire and again the next day to verify the data. Data collection was undertaken over a 12-week period from July to September 2002. Identical data were collected for refugees and nonrefugees. The London Central Office for Research ethics committees advised that ethical research approval was not necessary because only aggregated data were to be collected.

We asked for precise aggregated data on the number of inpatients and calculated the proportion of inpatients who were refugees. We used the actual numbers of inpatients as numerators to calculate inpatient rates per 100,000 population. For nonrefugees, we obtained denominators from the 2001 population census. We calculated inpatient rates for the total population of London as well as the adult population (aged 18 to 65 years).

The numbers of refugees living in London are notoriously difficult to estimate. The most recent and best estimates (3) suggested that between 352,000 and 422,000 asylum seekers and refugees were living in London in 2001. Of these, 4,000 were unaccompanied children (3). No other, more precise, demographic information was available from local, national, or international sources. For comparison with the nonrefugee inpatient rates, we calculated refugee inpatient rates by using estimates of the highest and lowest possible numbers of all refugees in London. To calculate adult inpatient rates of refugees, we used these figures minus the estimated number of unaccompanied children.

We could not adjust for age any further because we did not have any more precise demographic data on refugees. Although this deficiency highlights the need for better demographic information on refugees in the United Kingdom, from these data we were able to calculate rates for refugees by using all available denominators. We also calculated an admission ratio (refugee to nonrefugees): the ratio of observed to expected refugee admissions (under the assumption that refugees had the same admission patterns as nonrefugees).

Comparing refugees and nonrefugees, we also asked about detention under the powers of the Mental Health Act. Complexity of needs was assessed by the numbers of patients in need of interpreters, numbers no longer needing inpatient care, numbers for whom social factors prevented discharge, numbers using locked psychiatric intensive care facilities, and numbers of patients who had stayed for more than three months. We used nonparametric chi square tests, Spearman's correlation coefficients, and Fisher's exact tests for statistical comparisons of nonparametric data.

Results

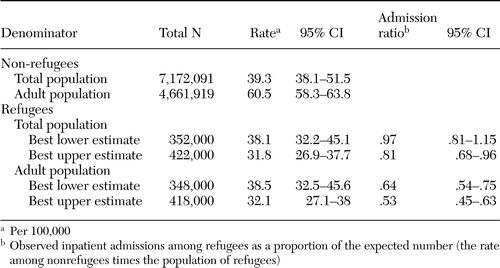

In the census week there were a total of 2,955 inpatients, of whom 134 (4.5 percent) were refugees. Across the sites, between 2.9 percent and 6.8 percent of inpatients were refugees (Fisher's exact p=.18). In contrast, the total inpatient rate across London varied widely, from 30.4 to 85.9 per 100,000 population (χ2=49.7, df=9, p<.001). This variation and its possible causes will be more fully described in a separate article. However, we established that the proportion of inpatients who were refugees was not related to the total number of inpatients or to bed availability. Admission rates and ratios indicated that refugees had admission rates that were similar to or lower than those of nonrefugees (Table 1).

Refugees were no more likely to be detained than nonrefugees (χ2=2.3, df=1, p=.13). Although male refugees were more likely to be detained than their female counterparts (54.1 percent compared with 46.1 percent; χ2=17.63, df=1, p<.001), there was no gender difference among refugees who were detained. Similar proportions of refugees (35 of 134, or 26 percent) and nonrefugees (879 of 2,821, or 31 percent) had been inpatients for more than three months. Refugees were not significantly more likely to be found in psychiatric intensive care units than nonrefugees (five of 134, or 3.7 percent, compared with 226 of 2,821, or 8 percent). According to the ward managers ratings, a greater proportion of refugees no longer warranted inpatient admission but could not be discharged until social issues, such as housing and legal status, were resolved (33 of 134, or 24.6 percent, compared with 444 of 2,821, or 15.8 percent; χ2=7.48 df=1, p=.006). A greater proportion of refugees needed interpreting services compared with nonrefugees (56 of 134, or 41.8 percent, compared with 101 of 2,821, or 3.6 percent; χ2=371.27, df=1 p<.001).

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study suggest that refugees are not overrepresented in London's psychiatric inpatient units. It may be that community services are bearing the greater burden of care or that refugees with psychiatric disorders are not gaining appropriate access to inpatient care (3,4). A previous study confirmed that Somali refugees used services in a chaotic manner that was not easily predicted by clinical needs (10). Alternatively, refugees may be healthier than the local population, given that people with psychoses are less likely to find their way to a country that provides asylum. Another explanation is that specific psychiatric disorders that are common among refugees—for example, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression—are unlikely to require admission.

Although these are the only data available to date, they must be interpreted with caution, because the actual number of refugees was small, and denominators for mobile populations may be inaccurate. Official government estimates include primary asylum applicants and not their dependents. Furthermore, we included migrants of uncertain legal status as refugees, which could have inflated our admission rates. A greater number of refugees, compared with nonrefugees, no longer warranted inpatient care and needed interpreting services. Nursing staff often confirmed that caring for refugees was more time-consuming and that it was complicated by accommodation and legal issues. The provision of health care to refugees requires further research to establish an objective view of health care needs and service provision. In all major world cities that offer asylum, future studies should focus on community and non-health care venues, specific diagnostic groups, and pathways to inpatient care.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by London's Mental Health Research and Development Virtual Institute (LoMHR&D).

Professor Bhui is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Barts and the London School of Medicine of Queen Mary University of London and with the East London and City Mental Health Trust. Dr. Audini and Dr. Duffett are with the Royal College of Psychiatrists' research unit in London. Dr. Singh is with the department of mental health of St. George's Hospital Medical School in London. Professor Bhugra is with the health services research division of the Institute of Psychiatry at King's College in London. Send correspondence to Dr. Bhui at Centre for Psychiatry, Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Barts and the London School of Medicine, Joseph Rotblat Building, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Refugees (N=134) and nonrefugees (N=2,821) among psychiatric inpatients in London, expressed as proportions of population estimates

1. UNHCR Asylum Statistics: Available at www.unhcr.ch/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/basicsGoogle Scholar

2. Home Office: Asylum Statistics, Second Quarter, 2003. Available at www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs2/asylum1203.pdfGoogle Scholar

3. GLA: Refugees and Asylum Seekers in London: A GLA Perspective. Available at www.london.gov.uk/mayor/refugees/docs/refugees_summ.pdfGoogle Scholar

4. Burnett A, Peel M: Asylum seekers and refugees in Britain: health needs of asylum seekers and refugees. British Medical Journal 322:544–547,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. De Jong JT, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M, et al: Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in 4 postconflict settings. JAMA 286:555–562,2000Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Bhui K, Abdi A, Abdi M, et al: Traumatic events, migration characteristics, and psychiatric symptoms among Somali refugees: preliminary communication. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:35–43,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Asylum system "damages health." BBC News Online, Monday, Dec 18, 2000. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/l/low/health/1076228.stmGoogle Scholar

8. Silove D, Manicavasagar V, Beltran R, et al: Satisfaction of Vietnamese patients and their families with refugee and mainstream mental health services. Psychiatric Services 48:1064–1069,1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Lelliott P, Audini B, Duffett R: A survey of patients from an inner London health authority in medium secure psychiatric care. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:1–31,2001Google Scholar

10. McCrone P, Bhui K, Craig T, et al: Mental health needs, service use, and costs of Somali refugees in the UK. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 111:351–357,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar