Characteristics of Insured and Noninsured Outpatients With Depression in STAR*D

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined data from the first 1,500 patients with major depressive disorder who were entered into the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) and compared baseline characteristics of outpatients on the basis of their insurance status. METHODS: We compared the demographic and clinical characteristics and the features of the presenting symptoms of outpatients with private insurance, public insurance, Medicaid and Medicare, or no insurance who were seeking treatment for depression. RESULTS: Valid insurance data were available for 1,452 patients. Compared with patients with private insurance, patients with public or no insurance were more likely to be members of a racial or ethnic minority group, unmarried, less educated, and unemployed. Patients were more likely to attend primary care clinics if they had public insurance (46 percent) compared with private insurance (34 percent) or no insurance (30 percent). Compared with the other groups, patients with public insurance had the greatest number and severity of comorbid medical conditions. In general, compared with patients with private insurance, those with public or no insurance had greater severity of depression, more comorbid psychiatric symptoms, lower life satisfaction scores, and greater functional impairment. These findings remained after the analyses adjusted for gender, employment, comorbid medical conditions, race, and duration of illness. CONCLUSIONS: Compared with patients with private insurance, those with public or no insurance had a more chronic, more severe, and more disabling form of depression.

Interest has increased in recent years in the setting and the source of payment for patients who seek care for depression, but the differences in clinical characteristics among patients who receive care on the basis of these criteria is not well understood. Most studies have examined differences between psychiatric and primary care, between managed and nonmanaged care settings, and, to a more limited extent, between insured and noninsured patients or between those with Medicaid and those with private insurance (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). Whether these groups differ in demographic variables, clinical features, presenting depressive symptoms, and medical and psychiatric comorbid conditions is of clinical interest, because such differences could affect clinical decision making and resource allocation.

The literature on access to health care clearly indicates that compared with those with private insurance, persons without insurance, and in some instances those with public insurance, underuse mental health services (9,10,12), despite the fact that uninsured persons have greater need in terms of probable mental or substance use disorders (10,13). However, data are lacking on baseline characteristics and prospectively observed outcomes of outpatients with depression grouped according to insurance status and treated in primary and specialty (psychiatry) care settings with guideline concordant care.

It has long been noted that socioeconomic status, which is related to insurance status, has a strong correlation with the prevalence and outcome of mental disorders, although the data for depression have been somewhat less compelling than those for other disorders (14). Comparisons between outpatients with depression from various socioeconomic strata have shown greater levels of anxiety, somatization, and a higher number of depressive episodes among patients with lower socioeconomic status (15); an association between an increased rate of depressive symptoms and lower educational attainment (16); and a relationship between income, marital status, age, education, and depression scores among women from racial or ethnic minority groups (17). Some of the studies in this area have evaluated nonclinical populations, and most studies have not considered additional factors, such as age, gender, and, particularly, physical illness, as suggested by Lorant and colleagues (14).

Previous work with large databases has shown that persons from racial or ethnic minority groups are overrepresented among patients who have no insurance or public insurance compared with those who have private insurance (6,9,10). From a clinical perspective investigators have compared treatment for depression among patients from racial or ethnic minority groups with such treatment among white patients (18,19,20,21,22,23). Although racial or ethnic minority status is not a perfect proxy for type of insurance or for socioeconomic status, findings from these studies may have relevance to comparisons addressed in this paper. In general, few major differences between groups in the nature of presenting symptoms have been found, although several studies reported greater levels of comorbid general medical and psychiatric conditions among patients from a racial or ethnic minority group (18,20,23), and some have reported differences in specific symptoms such as somatization and anger (19,21). Several studies have detected differences in the nature of treatment received and in the acceptance of various treatment modalities: compared with white patients, patients from a racial or ethnic minority group often receive older classes of antidepressants, are less frequently referred for counseling or psychotherapy, and are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care (9,22,23).

The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study (www.star-d.org) provides an opportunity to compare characteristics of, and eventually outcomes for, outpatients with depression whose source of payment varies from having no insurance to having public or private insurance (24,25). The report presented here is an exploratory analysis of the first 1,500 enrollees into STAR*D. We examined data from depressed outpatients who sought care in practice settings that provided either primary or psychiatric care and compared demographic and clinical characteristics and presenting symptom features by insurance status.

Methods

A complete description of the background, population, and methods of the STAR*D has been presented elsewhere (24,25). A brief summary of the study design, population, and outcome measures is provided here. Enrollment for the study began in July 2001 and ended in April 2004. The first 1,500 persons were enrolled by November 2002.

Study design

STAR*D aims to define prospectively which of several treatments are most effective for outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder, particularly those who do not respond to a first-line treatment. After providing written informed consent, participants were enrolled into the first level of treatment, a 12-week open trial with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Patients with an adequate clinical response were able to enter a 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase. Those who did not experience remission of their symptoms or who had unacceptable side effects were able to enter a series of subsequent levels of randomized treatments, including switch or augmenting strategies for medications and cognitive therapy (24,25).

Clinical sites

Each of the 14 regional STAR*D centers across the United States oversees the implementation of the protocol at two to four clinical sites that provide primary or psychiatric care in private care settings, public clinics, or Veterans Administration facilities. Clinical sites were identified that had significant numbers of outpatients with depression, adequate clinical and administrative support for the study, and significant numbers of patients from racial or ethnic minority populations.

Participants were grouped according to self-reported insurance status: private, public, or none. The public insurance category included patients with Medicaid or Medicare. Patients who had Medicaid or Medicare and additional private insurance were classified as being in the private insurance group. No attempt was made to ascertain the reasons patients had a particular kind or lack of insurance.

Study population

The study protocol was developed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All risks, benefits, and adverse events associated with protocol treatments were explained to study participants, who provided written informed consent (in English or Spanish) before study participation. Institutional review boards of each regional center approved the study.

A sample representative of outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder who were seeking treatment was generated by using the following inclusion criteria: outpatients aged 18 to 75 years for whom the treating clinician felt antidepressant medication was appropriate, a DSM-IV diagnosis of nonpsychotic major depressive disorder, and a score of 14 or greater on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17) (26,27). Possible scores on the HRSD-17 range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating more severe depression. Participants with suicidal ideation were eligible, as long as outpatient treatment was deemed safe by the clinician. Participants currently abusing substances were eligible as long as they did not require inpatient detoxification before study entry.

There were limited exclusion criteria: presence of general medical illnesses or concomitant medications that contraindicated a STAR*D treatment; lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder with psychotic features, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder; current primary diagnosis of an eating disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder; well-documented history of nonresponse or intolerability in the current major depressive episode to study treatments (in the first two treatment steps of the protocol); need for concomitant psychotropic medication (excluding anxiolytic or hypnotic medication); current engagement in evidence-based psychotherapy for depression (for example, cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal therapy); and pregnant or trying or intending to conceive within the next six to nine months.

Assesssments

At the initial screening (baseline) visit, a clinical research coordinator collected demographic and clinical information. Participants completed a modified paper-and-pencil version of the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ) (28), consisting of 123 yes-or-no questions that assess the symptoms of 13 DSM-IV disorders in five areas. The items on each diagnostic subscale were grouped together, with subscales clearly demarcated from each other. For the purpose of our study, the yes responses within each diagnostic subscale were summed and analyzed.

The clinical research coordinator administered the HRSD-17, the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated scale (QIDS-C-16) (29,30), and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) (31,32,33), which assessed the number and severity of general medical conditions. Three scores were generated from the CIRS: categories endorsed, indicating the number of the 14 domains with a comorbid condition (range, 0 to 14); severity index (range, 0 to 4), indicating the average severity score of the domains endorsed; and total severity, which combines the number of domains with the severity scores. The patient completed the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Rated (QIDS-SR-16) scale, a self-rated scale of depressive symptoms (29,30).

Within 72 hours of the baseline visit, the research outcome assessor used a telephone interview to complete the HRSD-17, the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician-Rated (IDS-C-30) scale (29,30,34,35), and the five-item Income and Public Assistance Questionnaire (IPAQ). An interactive voice response system collected information from the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) (36) to measure physical and mental health perceptions, and several quality-of-life measures, including the five-item Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (37), and the 16-item Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q) (38).

Data analyses

The analyses reported here were intended to be exploratory and aimed to identify potential differences for further hypothesis testing with the complete sample of 4,041 participants. For the comparison across insurance categories, percentages are presented for categorical sociodemographic variables (for example, race or ethnicity) within each group, along with the p values based on a chi square test comparing the rates across groups. Means and standard deviations are presented for continuous sociodemographic measures (for example, age), general medical conditions, measures of symptoms of comorbid psychiatric disorders, and measures of severity of depression. Parametric and nonparametric one-way analysis of variance models were used to compare differences among insurance groups.

Simple linear regression models, with insurance type (private, public, or none) as an independent variable, were used to asses the relationship between insurance type and measures of depression severity, function, and quality of life. Multiple regression methods were used to determine the independent effect of insurance status after the analyses controlled for the effect of gender, race, employment, duration of illness, and CIRS total score.

The association between insurance status and presence or absence of specific depressive symptoms as measured by each IDS-C-30 item was assessed by using a logistic regression model. Multiple variable logistic regression models were used to adjust for the effect of gender, race, employment, duration of current illness, and CIRS total score in assessing the relationship between insurance status and the presence of each symptom.

Statistical significance for all tests was set at p<.05. When significant differences were detected, pairwise post hoc tests were conducted with a Bonferroni correction. Because the analyses were exploratory, no correction for the testing of multiple variables was made, so results must be interpreted accordingly.

Results

Demographic characteristics

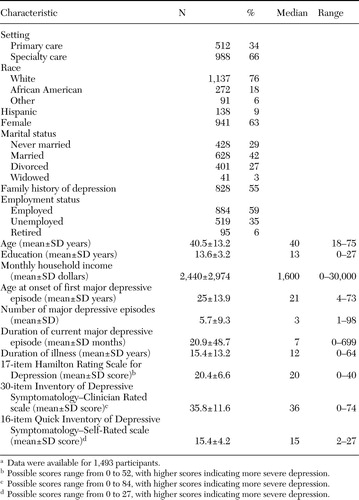

As shown in Table 1, the mean±SD age of the sample was 40.5±13.2 years, 63 percent were women, 76 percent were white, 18 percent were African American, and 6 percent were from another racial minority group. Nine percent were Hispanic. Almost two-thirds of the participants attended psychiatric care settings (988 participants, or 66 percent), and approximately one-third attended primary care settings (512 participants, or 34 percent). The mean HRSD-17 score was 20.4±6.6, and the median duration of the present episode of depression was seven months.

Comparisons among participants by insurance status

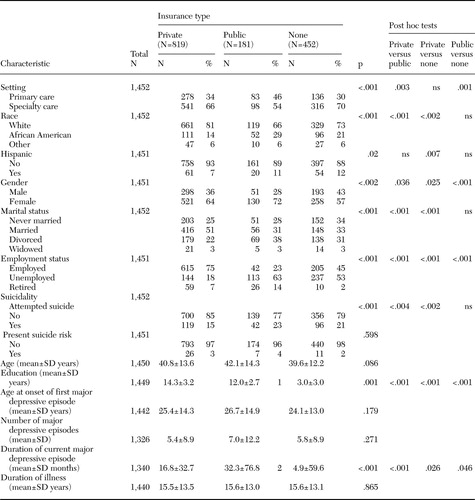

As shown in Table 2, valid insurance data were available for 1,452 patients: 819 patients (56 percent) had private insurance, 181 (12 percent) had public insurance, and 452 (31 percent) had no insurance. Significantly more patients with private or no insurance received specialty care treatment compared with those with public insurance (66 percent and 70 percent, respectively, compared with 54 percent; p<.001).

There was a significant difference in the distribution of racial categories across insurance groups (p<.001). After the analyses adjusted for multiple comparisons, there were statistically significant differences between publicly and privately insured individuals (p<.001) and between privately insured and uninsured individuals (p<.002). African Americans made up a larger percentage of both the public insurance and no insurance groups (29 and 21 percent) than of the private insurance group (14 percent). Patients of Hispanic descent represented 11 percent of patients in the public insurance group, 12 percent in the uninsured group, and 7 percent in the private insurance group (p=.02). However, the only significant pairwise difference, after the analyses adjusted for multiple comparisons, was between the private insurance group and the uninsured group (p=.007). Women made up 72 percent of the public insurance group, 64 percent of the private insurance group, and 57 percent of the uninsured group (p<.002).

No age differences were found between the insurance groups. Patients with public insurance had significantly less education than those with no insurance, who had significantly less education than those with private insurance (p<.001). Compared with patients with private insurance, those with public or no insurance were less likely to be married and more likely to have been divorced (p<.001). There were significant differences in employment across the three groups, with the highest rates of employment for patients with private insurance (75 percent), intermediate rates for those with no insurance (45 percent), and lowest rates for those with public insurance (23 percent; p<.001).

The duration of the current major depressive episode was significantly different for the three groups (p<.001); duration was longest for patients with public insurance (32.3 months), intermediate for patients with no insurance (24.9 months), and shortest for those with private insurance (16.8 months). Total length of time from the onset of illness, age at the initial episode of depression, and number of lifetime episodes of depression did not differ between the groups. Past suicide attempts were more common among patients with public insurance (23 percent) and those with no insurance (21 percent) than among those with private insurance (15 percent) (p<.001). No differences were found in assessed risk of current suicidal ideation across groups.

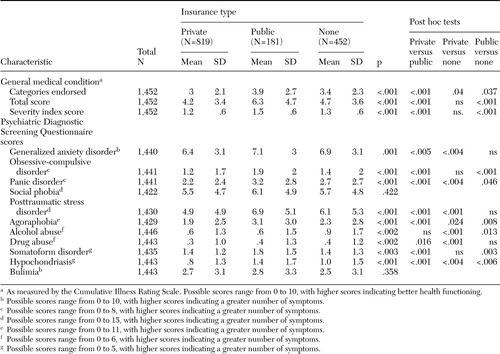

As shown in Table 3, the means of the three measures of general medical conditions differed across the insurance groups (p<.001). Patients with public insurance had significantly higher CIRS ratings in all categories than patients with private insurance. After the analyses adjusted for multiple comparisons, there were no statistically significant differences between patients with private insurance and those with no insurance. However, when patients with public insurance were compared with those with no insurance, the total score and severity index, but not the number of categories endorsed, were significantly higher among patients with public insurance after the analyses adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Table 3 also shows the PDSQ findings on the basis of symptom items, which were answered yes or no to identify the presence of each noted concurrent axis I condition. There was a statistically significant difference between the groups in the mean number of symptoms for nine of 11 psychiatric comorbid conditions. In all but one of these (alcohol abuse), patients with public insurance endorsed a higher number of symptoms, on average, than either of the two other groups.

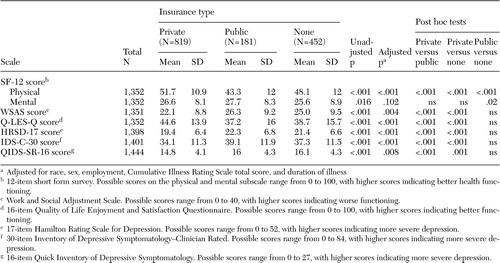

As shown in Table 4, analyses were conducted to assess the association between insurance status and measures of depression severity and quality of life. Adjusted analyses were conducted by taking into account gender, race, employment status, duration of illness, and total CIRS scores, variables that were significantly different across the groups and that may also be associated with measures of depression severity and quality of life. Adjusted analyses showed an independent relationship between insurance status on all measures of depression severity and quality of life, except for on the SF-12 mental health subscale. Post hoc comparisons revealed no statistically significant differences between patients with public insurance and those with no insurance. The post hoc comparison of patients with private insurance and those with public insurance showed significant differences for the SF-12 physical health subscale, WSAS scores, Q-LES-Q scores, HRSD-17 scores, QIDS-SR-16 scores, and IDS-C-30 scores, and post hoc comparisons of those with private insurance and those with no insurance showed significant differences for the Q-LES-Q scores, HRSD-17 scores, IDS-C-30 scores, and QIDS-SR-16 scores.

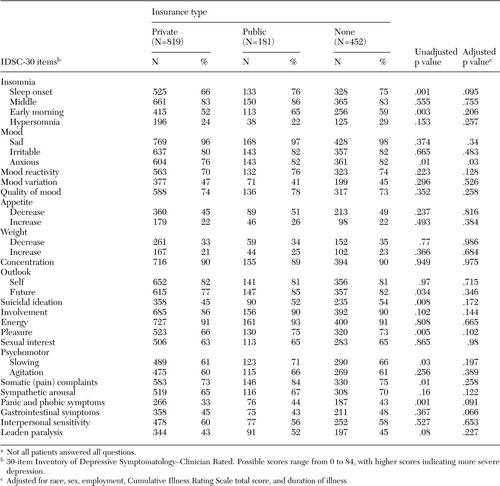

To determine whether, in addition to severity differences in depression, different depressive symptoms were endorsed among patients on the basis of insurance status, we compared the groups in terms of the presence of 30 items collected by the IDS-C-30, with and without adjustment for gender, race, employment, duration of illness, and total CIRS score. As shown in Table 5, we report the proportion of patients who endorsed a particular item. In the adjusted analysis, only one of 30 comparisons (anxious mood) had a p value of .03, indicating no apparent differences in the specific symptoms endorsed by members of each group.

Discussion

In this comparison of the initial 1,500 depressed outpatients who took part in STAR*D, we found that demographic factors (education, employment, and race or ethnicity) were significantly different across the groups, with the public insurance group and the no insurance group being more similar to each other than to the private insurance group. Patients with public insurance attended primary or specialty care settings in almost equal numbers, whereas patients with private insurance or no insurance were much more likely to attend specialty care. Medical burden was greatest among patients with public insurance and least among patients with private insurance. Patients with public insurance and those with no insurance had more severe depression, a longer duration of current depression, more previous suicide attempts, self-reported poorer quality of life, and worse functional status than patients with private insurance.

Many of the differences in demographic characteristics are to be expected, because they are inherent in the reasons why people have a particular type of insurance. For most demographic variables, with the notable exception of employment status, patients without insurance resembled those with public insurance. Patients without insurance probably reflect a heterogeneous population composed of significant numbers of working people with no health benefits, unemployed and poor people who do not qualify or have not applied for Medicaid, and noncitizens. Unfortunately, we do not have data that indicates why people did not have insurance—that is, whether this lack of insurance was by choice or because insurance was unaffordable or unavailable.

One interesting difference was that, similar to patients with private insurance, those without insurance were more likely to be seen in specialty care settings rather than in primary care settings. Patients without insurance may have had less medical burden, which led them to seek care in psychiatric rather than primary care settings. Or, if not for STAR*D, these uninsured patients may have routinely been seen less frequently in specialty practices. However, STAR*D pays for medications and treatment for patients who do not have coverage. Perhaps this treatment opportunity afforded private providers the resources to treat these patients, whom they otherwise could not treat. Patients with serious and disabling medical problems are more likely to have public insurance as a result of their illness, and coupled with their more severe depression, they put an added burden on staff in primary care settings where mental health resources may be scarce. Attention to this disparity might be an important factor in allocation of psychiatric staffing.

Previous work (1,3,4,7), as well as a preliminary report that used data from the same 1,500 patients described in this report (39), noted virtually no differences in depression severity or in symptom patterns among patients seeking care in primary clinics and those seeking care in specialty clinics, even though the medical burden was higher for those who attended primary care clinics. However, our data highlight the need to investigate the heterogeneity of patients who seek care in various settings, because we observed a substantially increased severity of depression among the patients without insurance who were seen in primary care. In our data set, patients without insurance made up a relatively small number of patients seen in primary care (about 17 percent), but they were the most impaired group. Not taking insurance status or some similar factor into account could obscure significant within-group differences. The increased severity and disability seen among patients with public insurance may be a reflection not only of medical burden but also of other factors acting in concert with this burden: decreased access to care because of physical and financial hardships, lack of resources (for example, transportation and daycare for children), higher dysfunction in the family or in the home situation, and less social support.

Patients with public insurance had a considerably longer current depressive episode than patients in the other groups, possibly because of increased symptom severity, underrecognition of the depression, stigma, comorbid psychiatric conditions, or delayed access to care (3,5,10,23). Patients with public insurance and those without insurance rated themselves as more functionally impaired than patients with private insurance on multiple dimensions, after the analyses controlled for gender, race, general medical conditions, employment, and duration of current illness. Depression and additional burdens related to life circumstances, poverty, and limited resources for dealing with hardships likely add to the functional impairment.

The lack of differences in presenting symptoms of depression deserves comment. The most frequently reported symptoms were sad mood, low energy, difficulty concentrating, and reduced interest and involvement. These symptoms provide a basis for rapid screening for depressive illness, as suggested by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Report (40). It appears that independent of the source of financial support for treatment, these symptoms were endorsed most frequently and deserve careful scrutiny by clinicians in whatever setting they are found.

Comparisons with other findings in the literature are difficult, as there have not been large-scale studies with patients grouped by insurance status. Similar to the findings from other studies, our study found that patients from lower socioeconomic strata had more severe depression, more comorbid medical problems, and lower quality-of-life ratings (13,15,18,19,20,2123). These findings remained significant even after the analyses controlled for factors that have confounded some of the studies that used socioeconomic status in the past.

Because of the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot comment on the temporal or causal directions of these associations. For example, we cannot say which is the case: that the factors contributing to an individual's having public insurance are the same factors that lead to the development of depression or that having depression results in a level of impairment that leads to an individual's having public insurance or no insurance. From a policy standpoint, inferences are difficult to draw (particularly without outcome data), other than noting that clinics with large public and, to a lesser extent, uninsured populations are likely to be faced with patients who have multiple psychiatric, medical, and psychosocial problems, necessitating the allocation of appropriate resources to manage these patients.

It is important to note several limitations of our study. First, participants were not drawn from a random sample that is fully representative of the population of patients with depression who seek care. Although STAR*D regional centers included sites from around the nation, they were not necessarily selected to represent all geographic regions or to include urban and rural areas. Second, treatment of depression in primary care as opposed to specialty care was unevenly distributed among groups, with patients with public insurance more likely than those in the other groups to receive care in primary care settings. Both of these reasons, combined with the fact that the patients' mean HRSD-17 scores were higher than is often reported at entry into clinical trials, somewhat limits the generalizability of these results, because entry into the study may not be reflective of clinical reality in the community. Third, it is not possible to determine the role of barriers to care or reporting bias in shaping the data in the study. Fourth, we did not have data on the temporal sequence of the depression onset and current insurance status, making it difficult to discern the direction of these associations. Finally, much of the data collected by the clinical research coordinators were generated solely by the participants and did not have external verification.

Conclusions

The extent to which our findings are related to treatment outcome remains to be seen. Several reports have noted that patients in public mental health clinics, many of whom were from a racial or ethnic minority group, had relatively low response or remission rates for episodes of major depression (41,42). However, a number of reports indicate that structured interventions can improve outcomes for poor and uninsured patients (43,44,45,46,47). The question remains whether patients with no insurance or public insurance who receive adequate and aggressive treatment in both primary and specialty clinic settings would have responses similar to patients with private insurance or whether their outcomes remain less than optimal despite adequate treatment. Data from the treatment phase of STAR*D will be able to address these questions because treatment procedures are closely managed in STAR*D.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by contract N01-MH-900-03 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas.

Dr. Lesser is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Box 8, 1000 West Carson Street, Torrance, California 90509 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Leuchter is with the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Trivedi, Ms. Stegman, and Dr. Rush are with the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Dr. Davis is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and with the research and development department at Tuscaloosa Veterans Administration Medical Center in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Dr. Wisniewski and Dr. Balasubramani are with the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Petersen is with the department of psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 1,500 patients with major depressive disorder who entered the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D)

|

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of patients with major depressive disorder who entered the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D)

|

Table 3. Association between insurance type and comorbid medical and psychiatric symptoms among patients with major depressive disorder who were entered into the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D), by insurance status

|

Table 4. Functioning and severity of depressive symptoms among patients with major depressive disorder who were entered into the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D), by insurance status

|

Table 5. Symptoms of 1,452 patients with major depressive disorder who entered the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR~D), by insurance statusa

aNot all patients answered all questions.

1. Cooper-Patrick L, Crum RM, Ford DE: Characteristics of patients with major depression who received care in general medical and specialty mental health settings. Medical Care 32:15–24,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Hays RD, et al: Subthreshold depression and depressive disorder: clinical characteristics of general medical and mental health specialty outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1777–1784,1994Link, Google Scholar

3. Schwenk TL, Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S: Differences between detected and undetected patients in primary care and depressed psychiatric patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 18:407–415,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Suh T, Gallo JJ: Symptom profiles of depression among general medical service users compared with specialty mental health service users. Psychological Medicine 27:1051–1063,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon GE, et al: Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Archives General Psychiatry 55:1121–1127,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Melfi CA, Croghan TW, Hanna MP: Access to treatment for depression in a Medicaid population. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 10:201–214,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Simon GE, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al: Treatment process and outcomes for managed care patients receiving new antidepressant prescriptions from psychiatrists and primary care physicians. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:395–401,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Smith JL, Rost KM, Nutting PA, et al: Resolving disparities in antidepressant treatment and quality-of-life outcomes between uninsured and insured primary care patients with depression. Medical Care 39:910–922,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55–61,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Sturm R, et al: Alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health care for uninsured and insured adults. Health Services Research 37:1055–1066,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Weilburg JB, O'Leary KM, Meigs JB, et al: Evaluation of the adequacy of outpatient antidepressant treatment. Psychiatric Services 54:1233–1239,2003Link, Google Scholar

12. Landerman LR, Burns BJ, Swartz MS, et al: The relationship between insurance coverage and psychiatric disorder in predicting use of mental health services. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1785–1790,1994Link, Google Scholar

13. Mauksch LB, Tucker SM, Katon WJ, et al: Mental illness, functional impairment, and patient preferences for collaborative care in an uninsured primary care population. Journal of Family Practice 50:41–47,2001Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, et al: Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology 157:98–112,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Lenzi A, Lazzerini F, Marazziti D, et al: Social class and mood disorders: clinical features. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 28:56–59,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Everson SA, Maty SC, Lynch JW, et al: Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 53:891–895,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Scarinci IC, Beech BM, Naumann W, et al: Depression, socioeconomic status, age, and marital status in black women: a national study. Ethnicity and Disease 12:421–428,2002Medline, Google Scholar

18. Brown C, Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ: Clinical presentations of major depression by African-Americans and whites in primary medical care practice. Journal of Affective Disorders 41:181–191,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wohl M, Lesser I, Smith M: Clinical presentations of depression in African-American and white outpatients. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health 3:279–284,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Jackson-Triche ME, Sullivan JG, Wells KB, et al: Depression and health-related quality of life in ethnic minorities seeking care in general medical settings. Journal of Affective Disorders 58:89–97,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Myers HF, Lesser IM, Rodriguez N, et al: Ethnic differences in clinical presentation of depression in adult women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 2:138–156,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al: The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care 41:479–489,2003Medline, Google Scholar

23. Rollman BL, Hanusa BH, Belnap BH, et al: Race, quality of depression care, and recovery from major depression in a primary care setting. General Hospital Psychiatry 24:381–390,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al: Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 26:457–494,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al: Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Controlled Clinical Trials, 25:119–142,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 23:56–62,1960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 6:278–296,1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI: The reliability and validity of a screening questionnaire for 13 DSM-IV Axis I disorders (the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire) in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:677–683,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Rush AJ, Carmody T, Reimitz P-E: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Clinician (IDS-C) and self-report (IDS-SR) ratings of depressive symptoms. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 9:45–59,2000Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, et al: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine 34:73–82,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L: Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 16:622–626,1968Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Miller MD, Towers A: A Manual of Guidelines for Scoring the Cumulative Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRSG). University of Pittsburgh, 1991Google Scholar

33. Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, et al: Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Research 41:237–248,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, et al: The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Research 18:65–87,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, et al: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine 26:477–486,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473–483,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, et al: The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:461–464,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, et al: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q): a new measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 29:321–326,1993Medline, Google Scholar

39. Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi M, et al: A direct comparison of presenting characteristics of depressed outpatients from primary vs specialty care settings: preliminary findings from the STAR*D clinical trial. General Hospital Psychiatry 27:87–96,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Pignone M, Gaynes B, Rushton J, et al: Screening for depression in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine 136:765–776,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Sirey JA, Meyers BS, Bruce ML, et al: Predictors of antidepressant prescription and early use among depressed outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:690–696,1999Abstract, Google Scholar

42. Meyers BS, Sirey JA, Bruce M, et al: Predictors of early recovery from major depression among persons admitted to community-based clinics. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:729–735,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al: Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research 38:613–630,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al: Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women. JAMA 290:57–65,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Smith JL, Rost KM, Nutting PA, et al: Resolving disparities in antidepressant treatment and quality-of-life outcomes between uninsured and insured primary care patients with depression. Medical Care 39:910–922,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Rush AJ, Crismon ML, Kashner TM, et al: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, Phase 3 (TMAP-3): rationale and study design. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:357–369,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Trivedi MH, Rush J, Crismon ML, et al: Clinical results for patients with major depressive disorder in the Texas Algorithm Project. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:669–680,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar