Factors That Influence Staffing of Outpatient Substance Abuse Treatment Programs

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined whether and how various organizational and environmental forces influence staffing in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. METHODS: The authors used data from the 1995 and 2000 waves of the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey (NDATSS), a telephone survey of unit directors and clinical supervisors. Multivariate analyses with generalized estimating equations were conducted. Two measures of staffing were modeled: the number of weekly treatment hours per client, and active caseload. RESULTS: Managed care activity influenced active caseloads but not the number of treatment hours per client. Significant differences were noted in staffing levels among private for-profit, private nonprofit, and public treatment programs, with public units offering fewer hours per client and having larger caseloads. Units accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations offered more treatment hours per client. CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study contribute to the understanding of various influences on treatment staff time and caseloads. Understanding these relationships is critical for policy makers, managed care companies, and managers, because staffing levels have the potential to affect both the cost and the quality of treatment.

Under an increasingly complex array of changing market, regulatory, and funding conditions, behavioral health organizations must make decisions about how limited resources should be allocated to provide services to clients. Many organizations struggle to provide high-quality care that corresponds to known standards and, at the same time, reduce or contain costs. Because treatment staff assume responsibility for the delivery of services, staffing decisions in behavioral health organizations are often at the heart of the trade-off between the cost and quality of treatment (1,2,3).

For example, in the substance abuse sector, managed behavioral care programs have grown (4), with a corresponding emphasis on outpatient treatment, cost control, and organizational efficiency. Because personnel costs typically represent a majority of operating expenses, they are likely targets for such cost-reduction efforts. At the same time, there is some evidence that the needs of clients of substance abuse treatment programs are increasing, including growing requirements to provide or coordinate the provision of medical, psychological, and social services (5,6). Efforts by regulators and payers to more specifically direct and monitor care through the use of treatment protocols and guidelines have also increased (7). Treatment organizations may increase staffing levels to meet new requirements and document compliance.

Despite increasingly conflicting demands on staffing in drug treatment programs, little is known about how these organizations respond and, more specifically, what organizational and environmental factors are associated with higher or lower staffing levels. Results of previous studies in this area have often been ambiguous about how various factors may influence staffing. The purpose of the research reported here was to determine whether—and specifically how—different organizational and environmental forces influence staffing of outpatient substance abuse treatment programs.

An important factor in the quality and outcomes of treatment is the amount of treatment time clients receive, typically measured by some form of staff-to-client ratio. Higher ratios have been consistently associated with more effective treatment, often because staff ratios are a proxy for the amount of time and attention clients receive from treatment staff (8,9). Thus, in theory, more treatment staff time per client represents a best practice for outpatient drug treatment.

Conversely, reduced staffing levels may have negative implications for client outcomes and client satisfaction with drug treatment processes. Specifically, there is evidence that the level and duration of treatment services are key predictors of treatment outcomes (10,11,12). Thus efforts to reduce or limit staffing levels may directly impede treatment processes and, ultimately, treatment outcomes. Furthermore, greater caseloads may affect satisfaction, engagement, and turnover among substance abuse treatment staff (13).

The delivery of treatment services is also subject to economic influences. For example, treatment duration may be shortened, treatment services limited, and staff time reduced as organizations seek to operate more efficiently, reduce the overall costs of treatment, and generally do more with less. Overall, the drug treatment sector has experienced declines in the level of revenues received from all sources; programs may need to reduce budgets simply to stay afloat financially, which could result in reduced staffing levels (14). For example, managed care firms may negotiate arrangements with treatment providers that reward efficiency rather than paying on a fee-for-service basis (15,16,17). In addition, managed care firms may increase the level of oversight and case management for their enrollees, limiting the number of treatment sessions allowed or setting specific requirements on the type or sequence of treatment services that clients may receive (18,19,20).

Previous research in mental health and acute health care settings has focused on the relationships between staffing ratios and organizational or client outcomes, with the assumption that more staff is better (8,21). However, multiple factors may influence staffing, and various influences could work to increase or decrease staffing levels, particularly with current conflicting pressures to increase both quality and efficiency. In the study reported here we examined six major factors that are likely to affect staffing levels: managed care, the professional qualifications of treatment staff, accreditation status, ownership (public, private not-for-profit, private for-profit), organizational affiliation (mental health center, hospital, freestanding), and client complexity, including whether the unit offers methadone treatment (22) and the proportion of clients who had dual diagnoses, who were unemployed, and who had previously received substance abuse treatment (23,24,25). In some cases, the predicted relationships are straightforward (for example, more complex clients require higher staffing levels), but, in other cases, the factors examined may work to increase or decrease the amount of treatment provided to clients.

Methods

This study used data from two nationally representative samples of outpatient drug abuse treatment units surveyed in 1995 and 1999-2000 as part of the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey (NDATSS), a longitudinal program of research into the organizational structure, operating characteristics, and treatment modalities of such units in the United States (26). In the NDATSS, an outpatient substance abuse treatment unit is formally defined as a physical facility whose resources are dedicated primarily (more than 50 percent) to treating persons with substance use problems on a nonresidential basis. The sample was specifically designed to represent the wide variety of organizations that constitute the nation's complex outpatient treatment system.

The details of the sampling method and procedures of the NDATSS are described in detail elsewhere (27). Briefly, the NDATSS uses a mixed-panel design, which combines elements from panel and cross-sectional designs. Units are selected for participation from a sampling frame of the most complete list of the nation's outpatient substance abuse treatment units, compiled by the Institute for Social Research (27,28). In each wave, the sample is stratified by public versus private status, treatment modality (methadone or nonmethadone), and organizational affiliation (hospital, mental health center, or other).

In 1990 we contacted 575 treatment units; some were panel units that had participated in the 1988 NDATSS, and some were from a systematic random sample of the 1990 population list. Of these units, 481 participated, for a response rate of 88 percent. In 1995 we recontacted units from the 1990 study and also selected a systematic random sample from the 1994-1995 population list. After screening and after nonresponse was taken into account, the total number of organizations that completed interviews in 1995 was 618, for a response rate of 86 percent. We followed a similar sampling process in 1999-2000, and 745 organizations completed interviews, for a response rate of 89 percent.

The director and clinical supervisor of each participating unit were asked to complete telephone interviews. After the data were collected, extensive reliability checks were performed within each survey, and results were compared between director and supervisor surveys to further confirm validity. These checks indicated high levels of consistency in the NDATSS data. The study protocols and methods were approved by the University of Michigan's institutional review board.

Measures

We were interested in the amount of treatment hours provided to clients in outpatient treatment units. We used two indicators of unit staffing: the number of treatment staff hours per client, and active client caseload. The first indicator is a ratio of the total number of staff hours allocated to treatment per week to the total number of outpatient substance abuse treatment clients treated per week. Although treatment staff may spend time on nontreatment activities, the ratio we used included only treatment hours. The second indicator, active caseload, is the number of active cases managed by each full-time treatment staff member. Together, these two indicators provide relatively independent perspectives on staffing levels. They allowed us to model influences on treatment time for treatment staff effort per unit of output (concentration) and the distribution of effort across units of output (dispersion). The indicators represent standard measures of staffing used by unit managers for business planning, resource allocation, and operational decision making (8).

Analysis strategy

We used generalized estimating equations (GEEs) (29) to test the relationships of interest, to test for changes over time, and to account for within-unit correlation over time. An important feature of the GEE approach is that parameter estimates have the same interpretation as parameters estimated by using generalized linear models (GLMs) for cross-sectional data. Also, GEEs do not require the correct specification of the within-unit correlation matrix. Such longitudinal approaches have the advantage that each unit essentially serves as its own control (30).

Because the dependent variables involve counts, we used log-linear models. Because one of these variables (total number of treatment staff hours) could be viewed as a surrogate for the size of the unit, we modeled that dependent variable by using an offset—for example, total number of clients—to adjust for unit size. We did not use a ratio-dependent variable—for example, number of staff hours per client—because to do so would have been to ignore the discrete nature of the outcome (31). For each dependent variable we fitted a model that included all covariates, time effects, and interaction effects for each predictor with time. Thus we allowed the relationship between dependent variables and predictors to change over time by including interaction terms representing the interaction of predictor variables with time. Only interactions that were significant were included in the final models. In analyses that used both waves, there were 1,133 unit-years, representing 864 distinct units. No individual variables were missing for more than 10 percent of cases, and we found no significant differences between cases in our model and those dropped because of missing data.

Results

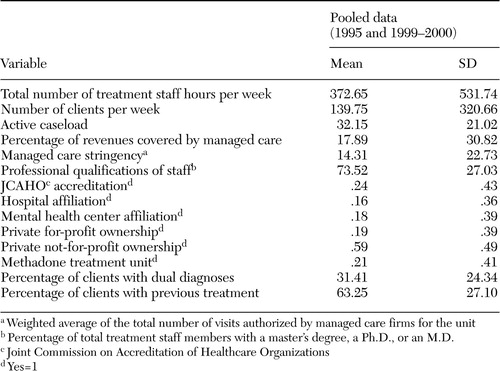

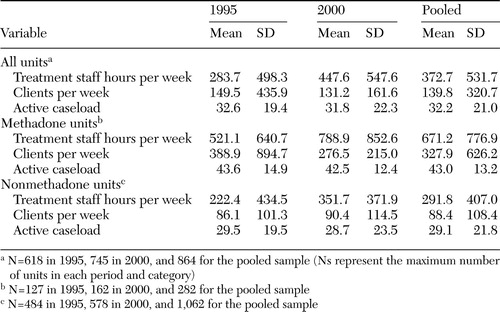

Means and standard deviations for each study variable at each wave are listed in Table 1. In our nationally representative sample, across both waves of data, outpatient treatment units provided an average of 2.66 staff hours per client per week, and treatment staff managed about 32 active clients. Table 2 lists means and standard deviations for the measures of staffing by year and for methadone and nonmethadone units. Treatment staff in methadone units managed a greater active caseload (a mean of 43) than staff in nonmethadone units (a mean of 29).

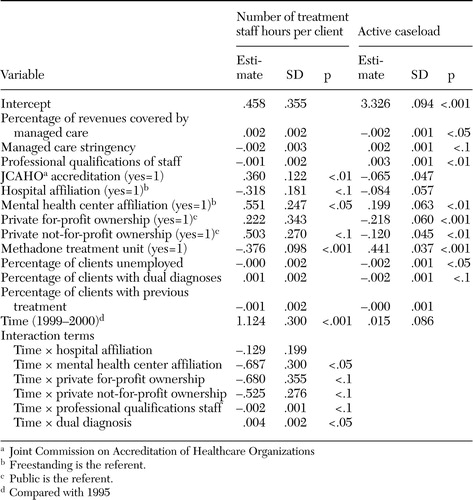

Results of the regression models are presented in Table 3. Because we found no major differences in results from the base model to the interaction model (except for terms that were components of the interactions), we summarize the full model results below for each dependent variable.

No significant relationships were found between the managed care factors, the professional qualifications of staff, and the number of treatment staff hours per client. However, units that had accreditation from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) provided more staff hours per client. Compared with public units, private not-for-profit units provided more staff hours per client. Some evidence was found that units affiliated with hospitals offered fewer staff hours per client than freestanding units. However, compared with freestanding units, mental health center-affiliated units had more staff hours per client. Units offering methadone treatment had fewer staff hours per client. No significant relationships were found between the percentage of clients with previous substance abuse treatment, the percentage of clients with dual diagnoses, and the percentage who were unemployed and staff hours per client.

Both managed care measures were significantly associated with active caseloads in outpatient substance abuse treatment units. Specifically, we identified a significant negative relationship between the percentage of revenues covered by managed care and caseloads and some evidence that greater stringency of managed care arrangements is associated with greater caseloads. The professional qualifications of staff (that is, the proportion of staff members with a master's degree, a Ph.D., or an M.D.) were associated with greater caseloads. We found no significant relationship between JCAHO accreditation and caseloads. Compared with public units, both private not-for-profit and private for-profit units had lower average caseloads.

Although no significant relationship was found between hospital affiliation and active caseloads, compared with freestanding units, mental health center-affiliated units had greater active caseloads. Units that offered methadone treatment had greater caseloads than those that did not. No significant relationships were found between the percentage of clients with previous substance abuse treatment and active caseload. The percentage of clients with dual diagnoses and the percentage who were unemployed were negatively associated with active caseload.

The regression results also indicated that some of the influences on treatment unit staffing were specific to the period studied. We compared the effects of each covariate in 1999-2000 with the effects in 1995. Several relationships were weaker in 1999-2000 than in 1995: the percentage of professional treatment staff and active caseload and the effects of private for-profit, private not-for-profit ownership, and mental health center affiliation with staff hours per client. The association between the percentage of clients with both drug abuse and mental health problems and active caseload was stronger in 1999-2000 than in 1995.

Discussion and conclusions

The motivation for this research was to examine various influences on staffing patterns in outpatient substance abuse treatment organizations. Understanding these relationships is critical for policy makers, managed care companies, and managers, because staffing levels have the potential to affect both the costs and the quality of treatment.

Despite the popular rhetoric and general anxiety about effects of managed care on substance abuse treatment practices, we found mixed evidence in terms of how managed care influences staffing. In some ways, managed care may result in improved substance abuse treatment. For example, in units that had greater managed care penetration, staff members had fewer clients to manage on an ongoing basis. This finding may have been due to managed care's requirements for documentation and case management activities, but, in the end, clients in these units may get more attention from staff.

On the other hand, units with more stringent managed care oversight experienced greater client caseloads, perhaps because greater stringency indicates the degree to which managed care organizations are actively seeking to limit or reduce treatment duration and costs. Thus greater caseloads may be a result of increased cost-control pressures that have forced treatment unit managers to eliminate or reduce staff and staff members who remain must manage a bigger caseload. Although managed care appears to influence substance abuse treatment staffing, our findings suggest that its effects are complex and may either improve (through smaller caseloads in units with greater managed care penetration) or impede (through higher caseloads in units with more stringent managed care relationships) high-quality treatment.

After we controlled for a variety of factors, staffing differences between public and private treatment facilities persisted, with public units exhibiting greater caseloads and fewer staff hours per client. This finding suggests that public units may struggle with pressures to cut costs and remain financially viable. What accounts for different staffing levels in public units? Public units may see a different mix of clients or offer a different mix of services than private units, including, for example, more involuntary clients or clients who are unable to pay for care. These differences between public and private staffing have implications for policy makers and public treatment unit managers. For example, public units are often the safety-net provider in their community. If clients in these units are not getting enough treatment time and counselors are overburdened with large caseloads, the net result may be poor outcomes for clients with few or no resources to seek care in private facilities. To the extent that managed care firms evaluate providers on the basis of the quality and effectiveness of treatment (15,16,17), public units' lower treatment time per client may result in their exclusion from managed care provider networks, further disenfranchising this part of the nation's treatment system.

The influence of organizational affiliation on staffing levels is a function of the type of affiliation rather than affiliation in general. Compared with freestanding units, hospital-affiliated units provided fewer staff hours per client, whereas mental health center-affiliated units provided more staff hours per client. At the same time, mental health center-affiliated units had greater active caseloads relative to freestanding units. These relationships are curious and may be subject to several possible interpretations. For example, hospital-affiliated units, together with their hospital partner, may offer a broader mix of medical and drug treatment services, with clients receiving fewer staff hours in the drug treatment setting and more staff time from medical and other health care providers in the hospital organization. By contrast, mental health center-affiliated units may offer an array of psychosocial treatment services in which clients receive care from social workers, mental health workers, and others who are based in the drug treatment unit itself. Thus, because of the more extensive range of in-house services provided, they may exhibit more staff hours per client than freestanding units.

Support for this explanation is found in other studies demonstrating that hospital-affiliated units provide greater access to primary care services through relationships with other providers and that mental health center-affiliated units are more likely to provide mental health services on-site than freestanding units (32). Our findings underscore the fact that organizational affiliation is associated with different treatment approaches and that treatment providers are influenced by the larger organizations that own or manage them.

JCAHO accreditation was associated with greater compliance with the "more is better" standard of care in terms of staff hours per client. Although other studies have had mixed results with respect to the effects of accreditation and its administrative and financial burden, our study showed that the overall effect of accreditation was positive with respect to treatment time. Managed care firms, governments, and consumers may use JCAHO accreditation as an indicator of units in which clients receive, on average, more treatment time. In an era of consumer-driven health care, this may be a useful proxy for treatment quality.

Unfortunately, a greater proportion of professional staff in outpatient substance abuse treatment units has not translated into more treatment time per client. Units with greater proportions of professional staff tend to rely on the skills and abilities of these staff members to manage larger caseloads. This relationship was weaker in 1999-2000 than in 1995, indicating perhaps that treatment managers have begun to see that there are limits to the number of active clients any staff member can manage, even those with advanced degrees.

Our findings suggest several areas for future research. For example, the precise relationships between staffing levels and treatment outcomes could be better documented (8). Further research can help identify the quality and cost implications of treatment organizations' responses to external and internal influences on staffing. Our study provides a solid foundation for this line of inquiry insofar as it has identified various factors that influence staffing levels in outpatient treatment units.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant 5-R01-DA-3272-18 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Dr. Lemak is affiliated with the department of health services research, management and policy of the University of Florida, P.O. Box 100195, Gainesville, Florida 32610-0195 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Alexander is Richard C. Jelinek Professor in the department of health management and policy of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of outpatient substance abuse treatment units in the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey (NDATSS): 1995 and 1999-2000 (N=1,133 unit-years)

|

Table 2. Staffing measures in a study of outpatient substance abuse treatment units, by year and for methadone and nonmethadone units

|

Table 3. General equalizing equation (GEE) regression results in a study of staffing in outpatient substance abuse treatment units (N=1,233 unit-years [864 distinct units])

1. McCue M, Mark D, Harless DW: Nurse staffing, quality, and financial performance. Journal of Health Care Finance 29:54–76,2003Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hall LM: Nurse staffing models as predictors of patient outcomes. Medical Care 41:1096–1110,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al: Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 288:1987–1994,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Alexander JA, Lemak CH, Campbell C: Changes in managed care activity in outpatient substance abuse treatment organizations, 1995–2000. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:369–381,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. D'Aunno T, Vaughn TE: An organizational analysis of service patterns in outpatient drug abuse treatment units. Journal of Substance Abuse 7:27–42,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Etheridge RM, Craddock SG, Dunteman GH, et al: Treatment services in two national studies of community-based drug abuse treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse 7:9–26,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lamb S, Greenlick MR, McCarty D: Bridging the gap between practice and research: forging partnerships with community-based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 1998Google Scholar

8. Coleman JC, Paul GL: Relationship between staffing ratios and effectiveness of inpatient psychiatric units. Psychiatric Services 52:1374–1379,2001Link, Google Scholar

9. Timko C, Sempel JM, Moos RH: Models of standard and intensive outpatient care in substance abuse and psychiatric treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 30:417–436,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Metzger DS, et al: Similarity of outcome predictors across opiate, cocaine, and alcohol treatments: role of treatment services. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:1141–1158,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. De Leon G: Integrative recovery: a stage paradigm. Substance Abuse 17:51–63,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Simpson DD: Effectiveness of Drug-Abuse Treatment: A Review of Research From Field Settings in Treating Drug Abusers Effectively. Cambridge, Mass, Blackwell, 1997Google Scholar

13. Knudsen HK, Johnson A, Roman PM: Retaining counseling staff at substance abuse treatment centers: effects of management practices. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 24:129–135,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hogan CM, Merrick EL: Financing of substance abuse treatment services, in Recent Developments in Alcoholism, vol 15: Services Research in the Era of Managed Care. Edited by Galanter M. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2001Google Scholar

15. Findlay S: Managed behavioral health care in 1999: an industry at a crossroads. Health Affairs 18(5):116–124,1999Google Scholar

16. Sturm R: Managed care risk contracts and substance abuse treatment. Inquiry 37:219–225,2000Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lemak CH, Alexander JA, D'Aunno TA: An organizational analysis of selective contracting in managed care: the case of substance abuse treatment. Medical Care Research and Review 58:455–481,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Liu X, Sturm R, Cuffel B: The impact of prior authorization on outpatient utilization in managed behavioral health plans. Medical Care Research and Review 57:182–195,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Galanter M, Keller DS, Dermatis H, et al: The impact of managed care on substance abuse treatment: a problem in need of solution. Recent Developments in Alcoholism 15:419–436,2001Medline, Google Scholar

20. Sosin M, D'Aunno T: The organization of substance abuse managed care, in Recent Developments in Alcoholism: Services Research in the Managed Care Era, vol 15. Edited by Galanter M. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2001Google Scholar

21. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Cheung RB, et al: Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA 290:1617–1623,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Etheridge R, Hubbard RL, Anderson J, et al: Treatment structure and program services in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 11:244–260,1997Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Simpson DD, Savage LJ, Lloyd MR: Follow-up evaluation of treatment of drug abuse during 1969 to 1972. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:772–780,1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Simpson DD: Treatment for drug abuse: follow-up outcomes and length of time spent. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:875–880,1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Alemi F, Stephens RC, Llorens S, et al: A review of factors affecting treatment outcomes: expected treatment outcome scale. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 21:483–509,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. D'Aunno TA: Treating Drug Abuse in America: Results From a Study of the Outpatient Substance Abuse Treatment System, 1988–1995. Ann Arbor, Mich, University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, Survey Research Center, 1996Google Scholar

27. Heeringa SG: Outpatient Drug Abuse Treatment Studies: Technical Documentation. Ann Arbor, Mich, University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, 1996Google Scholar

28. Adams TK, Heering SG: Outpatient Substance Abuse Treatment System Survey: Technical Documentation, 1999–2000. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, Service Research Center, Institute for Social Research, 2001Google Scholar

29. Zeger SL, Liang K-Y: Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 42:121–130,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL: Longitudinal Data Analysis. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 1994Google Scholar

31. McCullagh P, Nelder JA: Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed. London, England, Chapman and Hall, 1989Google Scholar

32. Friedmann PD, Alexander JA, Jin L, et al: On-site primary care and mental health services in outpatient drug abuse treatment units. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:1:80–94,1999Google Scholar