Self-Cutting and Sexual Risk Among Adolescents in Intensive Psychiatric Treatment

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify the relationships between self-cutting, sexual abuse, and psychological variables in predicting infrequent condom use among 293 adolescents in intensive psychiatric treatment. Logistic regression analyses indicated that being female, being Caucasian, having been sexually abused, and reporting less impulse control were predictive of self-cutting. Further analysis found that those who self-cut were three and a half times more likely to report infrequent condom use than those who did not self-cut, even after the analysis controlled for sexual abuse history and HIV prevention self-efficacy. Self-cutting is strongly associated with sexual risk behaviors, and adolescents who engage in self-cutting should be assessed carefully for sexual risk behaviors.

Prevalence rates of self-mutilation have been reported to be as high as 14 percent in a sample of 245 college students (1) and 14 percent in a community sample of 440 adolescents, with self-cutting being the most common form of self-mutilation (2). In a study of 76 adolescent psychiatric inpatients, 46 (61 percent) reported self-cutting behavior (3). Most explanations of self-mutilation have conceptualized it as an expression of distress (4), a coping strategy to relieve tension (5), an act used to regain control after a dissociative experience (4,5), or a product of impulsivity (6).

In addition to self-cutting, other forms of risk taking are common among adolescents, particularly sexual risk behaviors. Data from a recent national survey of adolescents indicated that adolescents frequently engage in behaviors that place them at risk for contracting HIV (7). For example, over 14 percent of high school students had had four or more sexual partners and more than one-third of sexually active teens had not used a condom at last intercourse. Psychiatric disorders have been linked to higher levels of HIV risk behavior, including unsafe sexual practices (8). Self-cutting has also been associated with factors related to HIV risk. The previously described study of 76 psychiatric inpatients found that 27 percent of self-cutters shared cutting instruments, putting them at risk via blood-to-blood contact (3). The same study found that adolescents who reported not using condoms during sex were 1.9 times more likely to have engaged in self-cutting.

No studies have examined the associations between self-cutting and sexual risk behaviors while controlling for the impact of general attitudes about risk or a history of sexual abuse, factors shown to be highly related to inconsistent condom use (9). This study examined the general demographic, attitudinal, and behavioral characteristics associated with self-cutting in a large sample of adolescents in intensive psychiatric treatment. Sexual abuse and psychological variables related to risk-- HIV related and in general--were further examined as predictors of condom use. Specifically, it was hypothesized that self-cutting would be associated with decreased condom use.

Methods

This study was part of a larger longitudinal study of adolescent HIV-risk behavior (9). Participants were recruited from psychiatric day schools and residential programs between 1997 and 1999. Participants were aged from 13 to 18 years old and not psychotic. Of 382 eligible youths, 310 (81 percent) were enrolled in the study after written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian. After complete description of the Rhode Island Hospital institutional review board-approved study, written informed assent was obtained from participants.

Participants completed baseline measures of HIV-related knowledge, perceptions of susceptibility to HIV, and self-efficacy in regard to HIV prevention skills, all of which have shown excellent reliability and internal consistency (9). Impulse control and self-restraint were measured using subscales of the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory (9). Hope was measured using the Children's Hope Scale (10). A chart review was conducted to identify the presence of a history of sexual abuse, as previously described (9). Participants were asked "Have you ever intentionally cut your body using pens, knives, razor blades, bobby pins, or other things?" The frequency of buying and using condoms was assessed by self-report. Responses for frequency of condom use during vaginal or anal sex were categorized as frequent (always or almost always) or infrequent (all other response categories). A measure of general attitudes toward risk, which included items such as "I do things my friends don't dare do," was also completed (9).

Univariate analyses were used to examine the relationships between self-cutting and demographic and psychological variables--HIV related and in general. A regression analysis was then conducted to identify variables predictive of self-cutting. Another regression analysis examined the association between self-cutting and sexual risk behaviors.

Results

Of the 310 participants, 293 (95 percent) answered the item related to self-cutting behavior. Of those 293, 172 (60 percent) were male, 211 (83 percent) were Caucasian, and 18 (7 percent) were African American. The mean age was 14.8±1.5 years. The diagnostic range was similar to that of other therapeutic settings. A total of 110 participants (38 percent) had mood disorders, 74 (29 percent) had impulse control disorders, and 27 (10 percent) had anxiety disorders. A total of 140 (48 percent) reported self-cutting behaviors. Female adolescents were significantly more likely to report self-cutting than males (χ2=18.91, df=1, p<.001). Caucasians were more likely than non-Caucasians to report this behavior (χ2=6.87, df=1, p<.01), as were those who reported a history of sexual abuse (χ2=8.42, df=1, p<.01). Self-cutting was not associated with age.

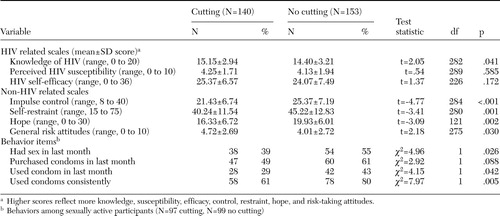

As shown in Table 1, self-cutting behavior was significantly associated with greater HIV knowledge. It was also associated with less impulse control, less restraint, greater hopelessness, and attitudes about general behavior that indicated risk taking. Compared with sexually active participants who were not self-cutters, sexually active participants who reported self-cutting were significantly less likely to report having had sex in the last month. They were also significantly less likely than noncutters to have used condoms in the past month and to have used them consistently.

The two logistic regressions used simultaneous entry of all classes of variables found to be significant in the univariate analyses. Gender, race, sexual abuse, and impulsivity that was not related to HIV attitudes were used in the first regression to determine predictive factors for the 174 self-cutters who had available data for all variables used in both regressions. In the second regression the same variables were used to assess the association of self-cutting with consistent condom use among the 110 sexually active participants for whom complete data were available. Self-efficacy in regard to HIV prevention skills was entered in both models because of its strong association with sexual risk behaviors in previous studies.

The first logistic regression found that all variables except HIV prevention self-efficacy were predictive of self-cutting (model χ2=39.69, df=5, p<.001). Self-cutting was associated with being female (OR=3.79, Wald= 12.18, p<.01), Caucasian (OR=2.65, Wald=4.59, p<.05), sexually abused (OR=2.05, Wald=4.24, p<.05), and impulsive (OR=3.34, Wald=11.47, p<.01).

In the second regression, infrequent condom use was associated with self-cutting (OR=3.58, Wald= 4.78, p<.05), a history of sexual abuse (OR=3.6, Wald=5.83, p<.05), and less self-efficacy in regard to HIV prevention (OR=2.96, Wald=4.14, p<.05). Gender, race, and impulse control were unrelated to the frequency of condom use (model χ2 =26.84, df=6, p<.001). Thus, even when gender, race, impulse control, sexual abuse, and self-efficacy were included in the model, self-cutters were three and a half times more likely to be inconsistent in condom use.

Discussion and conclusions

This study found that among a large sample of adolescents who were in intensive psychiatric treatment, self-cutters were significantly more likely to be female, to be white, and to have histories of sexual abuse. In addition, the findings expand understanding of self-cutters by identifying associations between self-injury and the general psychological factors of hopelessness, impulsivity, lack of self-restraint, and attitudes toward non-HIV-related risk. Even though the adolescents who were self-cutters had slightly more knowledge about HIV, they were three and a half times more likely to use condoms inconsistently, putting them at risk of contracting the virus.

This study also documents the important association between sexual abuse and both self-cutting and sexual risk behaviors. The relationship between self-injury and sexual risk taking existed even when the analysis controlled for sexual abuse history and psychological variables such as impulsivity and self-efficacy about HIV prevention. Thus self-cutting has an important and unique association with sexual risk behaviors apart from psychological factors that are the sequelae of sexual abuse. Two psychological processes may connect these behaviors. First, lack of self-restraint may lead adolescents to respond to internal impulses to injure themselves or to engage in sexual activity. Second, affect dysregulation, or the inability to manage strong emotions, may link self-cutting and sexual risk behaviors. This study did not examine reasons for self-cutting, such as affect dysregulation; however, adolescents with such deficits may attempt to self-soothe at moments of distress by engaging in self-cutting or risky sex. In addition, the potential for impulsivity and difficulty regulating emotions suggest that self-cutters may have high rates of other risk behaviors, such as suicidality, or forms of psychopathology, such as substance use disorders and personality disorders, which were not measured in the study presented here.

This study had several limitations. Self-cutting and condom use were assessed using only patient self-reports; however, they were assessed using confidential, adolescent-friendly methods. In addition, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for conclusions about causality between self-cutting and condom use, or whether other variables account for this relationship.

Understanding correlates of self-cutting is critical to psychiatric care. Providers can detect self-cutting more frequently than other risk behaviors because it can be observed, because it elicits concerned responses from parents, and because adolescents may be more likely to disclose self-cutting to clinicians than other risk behaviors. Self-cutting frequently raises clinicians' concerns about a patient's potential for suicidal behavior and drug use. However, the strong relationship between self-cutting and sexual risk behavior observed in this study suggests that treatment providers must consider a range of risk behaviors in treatment planning, recognizing that impulsivity and affect dysregulation may take many forms. Self-cutters appear particularly vulnerable to harm given the association with impulsivity, hopelessness, and sexual risk behavior. Other factors that may link self-cutting and sexual risk behavior should be examined in future research.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant R01-MH611-49 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and human behavior at Rhode Island Hospital and the department of psychiatry at Brown University Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Suite 204, Providence, Rhode Island 02903 (lk [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Scale scores and behaviors of 293 adolescents in intensive psychiatric treatment, by whether or not they reported self-cutting

1. Favazza AR, DeRosear L, Conterio K: Self-mutilation and eating disorders. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviors 19:352–361, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ross S, Heath N: A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 31:67–77, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

3. DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE, Hartley D: Prevalence and correlates of cutting behavior: risk for HIV transmission. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30:735–739, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

4. Suyemoto KL: The functions of self-mutilation. Clinical Psychology Review 18:531–554, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Sharkey V: Self-wounding: a literature review. Mental Health Practice 6:35–37, 2003Google Scholar

6. Herpert S, Sass H, Favazza A: Impulsivity in self-mutilative behavior: psychometric and biological findings. Journal of Psychiatric Research 31:451–465, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance-United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 53(SS-2):1–96, 2004Google Scholar

8. Brown LK, Danovsky M, Lourie K, et al: Adolescents with psychiatric disorders and the risk of HIV. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:1609–1617, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

9. Brown LK, DiClemente RJ, Beausoleil N: Comparison of HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors among sexually active and abstinent young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 13:140–145, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Snyder CR, Hoza B, Pelham WE, et al: The development and validation of the Children's Hope Scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 22:399–421, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar