Intensive Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Outpatients With BorderlinePersonality Disorder Who Are in Crisis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the effectiveness of an intensive version of dialectical behavior therapy for patients in an outpatient setting who met criteria for borderline personality disorder and who were in crisis. METHODS: Over the two-year study period, 127 patients (103 women) between the ages of 18 and 52 years were referred to the program; 87 were admitted, and because of a limited number of places, 40 were referred elsewhere. Patients were admitted after recent suicidal or parasuicidal behavior, and the most suicidal patients were given priority. The treatment was a three-week intensive version of dialectical behavior therapy consisting of individual therapy sessions; an emphasis on skills training provided in groups, including mindfulness skills; and team consultation. A diagnostic interview was administered, and patients were screened with the International Personality Disorder Examination Screening Questionnaire, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), and the Social Adaptation Self-Evaluation Scale. RESULTS: The only significant difference at intake between patients admitted to the program and those referred elsewhere was a slighter higher incidence of antisocial traits in the latter group. Of the 87 patients admitted, 71 (82 percent) completed the program and 16 (18 percent) dropped out. Pre-post analysis showed significant improvement in scores on the BDI and BHS. CONCLUSIONS: The three-week, intensive version of dialectical behavior therapy was found to be an effective treatment. Treatment completion was high, and patients showed statistically significant improvements in depression and hopelessness measures. This approach allowed therapists to treat a large number of patients in a short time.

Borderline personality disorder is an inherently complex disorder, with high morbidity and mortality. Patients meeting criteria for the disorder have been shown to be high users of all types of psychiatric treatment and to have more expensive inpatient stays (1). Recent American Psychiatric Association guidelines for the treatment of borderline personality disorder highlight some of the problems that may be encountered by health care providers (2). Under the rubric of "psychiatric management" the guidelines draw attention to the need for a structured and coherent approach to managing the patient, particularly for crisis management. Unfortunately, little research has been conducted on the efficacy of short-term treatments. The guidelines further recommend long-term psychotherapy for problems of poor interpersonal relationships and social functioning. Two approaches have been validated in prospective randomized controlled trials, psychoanalytic-psychodynamic therapy and dialectical behavior therapy (3,4).

The effectiveness of standard outpatient dialectical behavior therapy was initially demonstrated in a randomized clinical trial (4), in which the control group received the usual psychiatric treatment for borderline personality disorder. The one-year study of 44 patients found significant differences in the frequency and severity of parasuicidal behavior, treatment adherence, and hospitalizations. Follow-up studies showed that gains were maintained and that patients in the dialectical behavior therapy group had less anger and better social adjustment (5,6).

Dialectical behavior therapy (7,8) has already been successfully implemented in several settings (9), including a partial hospital program (10). We developed a shortened intensive version of this treatment for patients in crisis. In our health district, approximately 200 new patients who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder are hospitalized each year, many for suicidal behaviors. We sought to be creative in channeling our resources to create an effective treatment that would obviate the need for hospital treatment and that could also be aimed at more patients, an approach that corresponds more closely with the needs of public health systems.

The aim of the study reported here was to examine the intensive program over a two-year period and to assess the effectiveness of this version of dialectical behavior therapy on measures of depression, hopelessness, and social functioning.

Methods

The study was conducted at the outpatient treatment program for borderline personality disorder at the department of psychiatry at the University of Geneva. The program began in 1998. The study ran from the beginning of January 2000 until the end of December 2001. Fully informed, written consent was obtained from all participants. Helsinki principles were followed.

Participants

Data for all patients who were referred to our treatment program during the study period are included in this report. During the study period, 127 patients were referred to the intensive program—103 women (81 percent) and 24 men (19 percent). The patients were between the ages of 18 and 52 years (mean±SD= 30.7±8.1). Their mean educational level was equivalent to 12 years of study (mean=11.6±2.1), which comprised nine years of obligatory schooling followed by an apprenticeship, vocational training, or college. Sixty-four patients (50 percent) were single, and 41 (32 percent) had a professional activity. The number of lifetime hospitalizations ranged from 0 to 44 (mean=3.3±6), and the total number of days hospitalized ranged from 0 to 431 (mean=54±92.4). The mean age of first admission for the sample was 29±7.6 years. All patients had had previous psychiatric treatment, often in emergency services.

The program does not admit patients who present spontaneously; all patients must be referred by a physician. The program admits patients whose main problems are recent suicidal or parasuicidal behavior, severe impulsive disorders, anger problems, or multiple therapeutic failures in other treatment programs. The number of places in the program is limited. Patients who were considered to be the most suicidal were preferentially offered admission. The relative risk of suicide was determined by the receiving clinician. A total of 100 patients (79 percent) had made at least one suicide attempt (lifetime prevalence), and 112 (88 percent) had a history of at least one parasuicidal act, defined as intentional self-injury either with or without intent to die. Patients whose principal problem included a psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, developmental disturbance, substance dependence, or an eating disorder were not considered for admission to the program. After assessment, 87 patients (69 percent) were admitted to the program. The other 40 patients (31 percent) were referred for treatment elsewhere.

Of the 87 patients who were admitted, 71 (82 percent) completed the program and 16 (18 percent) dropped out. The patients who completed the pre- and post-measures were considered to have completed the program.

At the end of the treatment period, all patients, including those who dropped out, were referred for further treatment. In some cases the recommendation was to repeat the intensive program. Only data for patients' initial participation in the program were included in the study.

Assessments

All patients underwent a detailed clinical assessment at intake. Axis II pathology was assessed with the International Personality Disorder Examination Screening Questionnaire (11). This self-report instrumentconsists of ten subscales, each one corresponding to a personality disorder. Generally, a score greater than 3 on a subscale is used to indicate the presence of a personality disorder. In this study, the more stringent cut-off of 4 was adopted to reduce false-positives.

Several self-report measures were used. The 21-item version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) evaluated the intensity of depression (12), the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) estimated pessimism (13), and the Social Adaptation Self-Evaluation Scale (SASS) (14) assessed social functioning. This scale was added after the study had already begun.

Program description

The program is located in an outpatient unit that is a hybrid of a day hospital and a crisis center. The center is open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Patients may spend a maximum of two consecutive nights in the center, on a purely voluntary basis, and thus avoid hospitalization. After initial assessment, patients retained in the program may benefit immediately from crisis support, which is particularly useful at night and on weekends.

The intensive program is an adaptation of dialectical behavior therapy and offers individual and group therapy as well as a consultation team for therapists. All patients have an individual therapist who works with them to define one—or occasionally more—behavioral targets that will be the focus of treatment. These targets are selected within a strict dialectical behavior therapy framework, that is, suicidal behaviors are treated as a priority, followed by behaviors that interfere with therapy, and then by behaviors that interfere with quality of life. Given the short duration of the program, behavioral targets that are further downstream, such as decreasing behavior related to post-traumatic stress and increasing self-respect, are less frequently the focus of treatment.

The intensive program lasts for three weeks. Groups are organized on four of the five weekdays, for two to four hours each day, for three weeks. Most group work consists of behavioral skills training, which is taught intensively for a total of about six hours a week. The skills cover the four modules of dialectical behavior therapy—mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance, with a particular emphasis on mindfulness. In addition, groups are held before and after each weekend to deal with contingency management, skills generalization, and problem solving. A separate group teaches behavioral chain analysis, and another group helps patients to identify and name bodily sensations and emotional responses and to generalize mindfulness skills. All groups encourage behavioral rehearsal and, when appropriate, exposure.

Availability of limited telephone contact with therapists is another important feature of treatment. Patients participating in the program are given a special number to call. Between 8.30 a.m. and 6 p.m. a team member will route the call to their therapist if necessary, deal with crisis situations, encourage attendance, and help with skills generalization. Outside of these hours, patients may call the center for crisis support, but their call will be dealt with by the nurse on duty.

The primary therapist does not prescribe or manage psychotropic medications. All patients are evaluated for and offered medication as appropriate by one of the psychiatrists in the program.

Patients receive 13 hours of group therapy a week plus individual sessions. However, to maximize generalization to the natural environment, the program offers patients a very supportive environment but not occupational therapy. When patients are not actively in treatment they are encouraged to pursue their own lives, look for employment, and so forth.

The program therapists are two psychiatrists, one clinical psychologist, and five nurse clinicians. The psychiatrists and three of the nurse clinicians have received intensive training in dialectical behavior therapy. Training for the other team members is provided in ongoing weekly theoretical and case supervision sessions. In accordance with the principles of dialectical behavior therapy, all therapists are obliged to attend weekly team meetings, which include mindfulness practice.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Systat version 8.0. Pre-post differences for patients treated in the intensive program were computed with the paired-samples t test. Effect sizes as defined by Cohen (15) were also computed to measure the extent of therapeutic change. To compare clinical and demographic characteristics of patients who completed the intensive program with those who were referred elsewhere or who dropped out, the independent-samples t test was used for continuous variables and the chi square test for categorical variables.

Results

Program completion

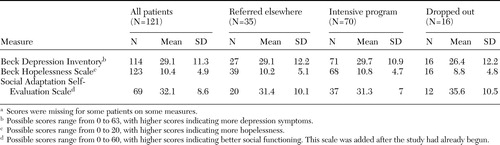

Treatment completion was high. Only 16 of the 87 patients (18 percent) who were admitted to the program dropped out. Five patients dropped out because they were hospitalized; however, no other single demographic or clinical variable predicted dropout. In terms of participation, the patients who dropped out missed most of the groups by the end of the first week, in marked contrast to those who completed the program, who attended the vast majority of groups and individual sessions over the three-week period. As shown in Table 1, no significant differences were found in the mean pretreatment scores of patients who completed the intensive program, those who dropped out, and thosewho were referred elsewhere.

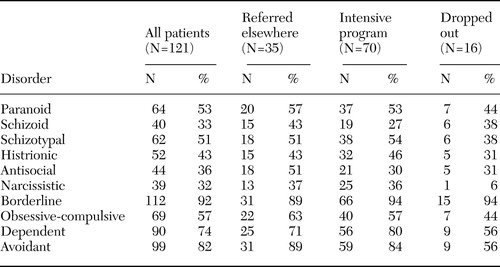

Screening for personality disorders

As expected, of the entire sample of 121 patients, 112 (92 percent) screened positive on the borderline personality disorder subscale (Table 2). In addition, cluster C personality disorders as described in DSM-IV(16)—avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive—were heavily represented. The patients who were not retained in the program were found to have significantly more antisocial traits (χ2=4.59, df=1, p<.05). Compared with those who dropped out, patients who completed the program had more dependent traits (χ2=3.98, df=1, p<.05) and avoidant traits (χ2= 6.19, df=1, p<.05).

Clinical outcome measures:

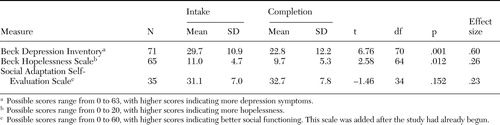

As shown in Table 3, after completion of the intensive program, significant improvements were observed in BDI scores and BHS scores. No statistically significant change was observed in SASS scores. A medium effect size was seen for BDI scores and a small effect size for BHS scores. No subgroup of patients with particularly marked clinical improvement or worsening was detected.

Discussion

This naturalistic study examined the effectiveness of a modification of dialectical behavior therapy for patients in a public health system who met criteria for borderline personality disorder and who were in crisis. A desire to offer effective treatment to the maximum number of patients was the primary reason for developing the program. The findings may be contrasted with those of more rigorously conducted clinical trials with stricter exclusion criteria and fewer patients (17).

The study yielded four main findings: the treatment was well tolerated by the patients, as evidenced by the high completion rate (82 percent) and low hospitalization rate (6 percent); the treatment was amenable to patients in crisis; significant improvements in hopelessness and depression were seen; and experienced clinicians with sufficient training in dialectical behavior therapy were able to master and successfully implement the technique.

Several common characteristics of effective treatments for personality disorders have been described (18), including a defined structure, attention to compliance, clear focus, theoretical coherence for patients and therapists, long-term duration, development of an attachment relationship, and good integration with other services. The treatment described in this report has all of those features, except that it is of short duration and high intensity because it was developed as a crisis treatment. It seemed to us that the strengths of a structured relational approach should not be reserved only for patients who have decided to undergo psychotherapy but should also be offered to patients who come into contact with health providers because they are in crisis. Effective, compassionate, and nonjudgmental care that is highly specific to patient's needs may not only be effective but may also increase the likelihood that patients will agree to further treatment. These elements probably explain the high retention rate.

The intensive program was organized to do the most with the least. The aim was to avoid hospitalization and at the same time work very intensively with the patients to achieve therapeutic goals. The total length of patients' stay was one month, covering the three-week intensive program and the assessment and termination sessions. This short period was chosen to allow time for meaningful clinical improvement but to avoid expending precious resources for months on end for a relatively small number of patients. This approach allowed the team of therapists to treat a large number of patients. Although the approach may maximize resources in terms of therapists, it may also explain the absence of improvement in social functioning, which would require longer-term treatment.

Significant improvements in hopelessness and depression were seen in a short period of time. It has been suggested that the efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy may be attributed to "initial improvement on multiple variables relevant to outcome in borderline personality disorder" (19). Certain aspects of depression, particularly hopelessness, are strongly associated with borderline personality disorder (20). Patients with increased suicide risk have been shown to have a higher level of hopelessness whether they have borderline personality disorder, major depression, or combined borderline personality and major depression (21,22,23). Comorbid major depression and borderline personality disorder increases the number and the seriousness of suicide attempts (23). Interventions to reduce depressive symptoms and hopelessness should be a priority in the management of borderline personality disorder.

Why did our patients show such a rapid reduction in their depressive symptoms, whereas patients in an impressive study of partial hospitalization did not show significant changes in depressive symptoms until after nine months (3)? In that treatment, like the intensive program, individual therapy, group work, and psychotropic medication were available. There is obviously no easy answer, because clearly many factors are involved. It could be that an emphasis on antidepressant medication in our program played an important role. Dialectical behavior therapy was developed for suicidal patients who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder. Is a combination of this therapy with appropriate medication even better suited to these patients?

In our experience with dialectical behavior therapy, we were particularly struck by the high level of patients' participation. We wondered whether their participation was linked to the considerable time spent on mindfulness. Mindfulness is a skill that develops awareness and that is antithetical to impulsive behavior. Mindfulness has been shown to be effective in the prevention of relapse in depression (24). Beneficial effects have been more marked with early-onset and recurrent depression, which may more closely resemble the misery of patients who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder. Perhaps cultivation of mindfulness is a unique way to approach suffering that is not easily amenable to conventional treatment; it allows a patient to live with suffering and at the same time helps alleviate it.

The study had several limitations. It was an uncontrolled study, and thus we cannot claim specific treatment effects for our program. In addition, although the participants had recently demonstrated a high level of suicidal and parasuicidal behavior, we have no specific measures of the outcome of these behaviors. The study period was short, and further work is required to determine whether therapeutic gains are maintained.

Conclusions

Intensive outpatient dialectical behavior therapy may be a particularly good approach to use with patients in crisis who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder in the public health system. We saw significant changes in depression and hopelessness over a relatively short period of time in a large number of patients. Retention rates were extremely high.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Hôpitaux Universitiares de Genève, Ch. du Petit-Bel-Air 2, 1225 Chêne-Bourg, Switzerland (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Scores on self-report measures at intake of patients who were considered for admission to an intensive program for patients with borderline personality disordera

a Scores were missing for some patients on some measures.

|

Table 2. Patients being considered for admission to an intensive program for patients with borderline personality disorder who were in crisis and screened positive on the International Personality Disorder Examination Screening Questionnaire

|

Table 3. Scores on self-report measures of participants in an intensive program for patients with borderline personality disorder at intake and at completion of the program

1. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al: Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:295–302, 2001Link, Google Scholar

2. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 158(suppl 10)1–52, 2001Google Scholar

3. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1563–1569, 1999Link, Google Scholar

4. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:1060–1064, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE: Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:971–974, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, et al: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1771–1776, 1994Link, Google Scholar

7. Linehan MM: Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

8. Linehan MM: Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

9. Swenson CR, Torrey WC, Koerner K: Implementing dialectical behavior therapy. Psychiatric Services 53:171–178, 2002Link, Google Scholar

10. Simpson EB, Pistorello J, Begin A, et al: Use of dialectical behavior therapy in a partial hospital program for women with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Services 49:669–673, 1998Link, Google Scholar

11. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al: The International Personality Disorder Examination: The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:215–224, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al: An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 4:561–567, 1961Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, et al: The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42:861–865, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Bosc M, Dubini A, Polin V: Development and validation of a social functioning scale, the Social Adaptation Self-evaluation Scale. European Neuropsychopharmacology 7 (suppl 1):S57–70, 1997Google Scholar

15. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

16. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

17. Scheel KR: The empirical basis of dialectical behavior therapy: summary, critique, and implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 7:68–86, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Bateman AW, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of psychotherapeutic treatment of personality disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:138–143, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Westen D: The efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 7:92–94, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Rogers JH, Widiger TA, Krupp A: Aspects of depression associated with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:268–270, 1995Link, Google Scholar

21. Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, et al: Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68:371–377, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Malone KM, Oquendo MA, Haas GL, et al: Protective factors against suicidal acts in major depression: reasons for living. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1084–1088, 2000Link, Google Scholar

23. Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Kelly TM, et al: Characteristics of suicide attempts of patients with major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder: a comparative study. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:601–608, 2000Link, Google Scholar

24. Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JM, et al: Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68:615–623, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar