Brief Reports: Assessment of Police Calls for Suicidal Behavior in a Concentrated Urban Setting

Abstract

As a result of deinstitutionalization over the past half-century, police have become frontline mental health care workers. This study assessed five-year patterns of police calls for suicidal behavior in Toronto, Canada. Police responded to an average of 1,422 calls for suicidal behavior per year, 15 percent of which involved completed suicides (24 percent of male callers and 8 percent of female callers). Calls for suicidal behavior increased by 4 percent among males and 17 percent among females over the study period. The rate of completed suicides decreased by 22 percent among males and 31 percent among females. Compared with women, men were more likely to die from physical (as opposed to chemical) methods (22 percent and 43 percent, respectively). The study results highlight the importance of understanding changes in patterns and types of suicidal behavior to police training and preparedness.

One of the major sociostructural changes of the past half-century has been the deinstitutionalization of care for people with chronic mental illness. This shift from custodial to outpatient care has occurred in developed countries around the world (1). Changing legislation has strengthened the legal rights of individuals with mental illness. However, often state funding has not met the increased need for community-based treatment programs. The result has been a downsizing of psychiatric hospitals, a reduction in the number of psychiatric beds available in psychiatric and general hospitals alike, and a concomitant increase in the number of people with chronic mental health problems who survive in the community.

Suicide and attempted suicide represent a unique and growing mental health problem. In 1997 just over 3,600 people died from suicide in Canada. North American studies indicate a growth in the suicide rate among young males, and this rate is higher in Canada than in the United States (2). Data from Health Canada indicate that suicide was the second leading cause of death for persons aged 15 to 29 years from 1989 to 1991. Suicide is also a significant problem among elderly persons, with men accounting for up to 80 percent of all suicides in this group (3). Suicide among elderly persons has been linked to widowhood, low referrals for treatment, undiagnosed depression, and cohort size (3,4). Reported ratios of suicide attempts to completed suicides vary considerably from a low of 10:1 to a high of 100:1, most likely reflecting the lack of reliable data on suicide attempts.

Law enforcement agencies have a long history of community intervention with persons with mental illness, although the intensity of their involvement and the nature of their interactions has altered over time. Because of deinstitutionalization, these agencies play an increasingly important role in the management of persons with psychiatric illness. North American research suggests that police officers are the primary referral source for psychiatric emergency departments (5). In a U.S. study, Borum and associates (6) found that up to 7 percent of monthly contacts for the police involved persons with mental illness. For police, interaction with mental health professionals can be frustrating and time-consuming because of delays in consultation during the referral process. Mental health professionals may not agree with police officers' judgment of the severity of the situation and may choose not to admit a person to the hospital. In other circumstances, mental health professionals quickly release a detained person whom the police have deemed to be a menace to the community (5). This revolving-door situation means that police officers encounter many of the same individuals again and again in the community.

Because of the varied demographic characteristics associated with suicidal behavior, police officers are expected to deal with depression among elderly persons, anger and frustration among youths, and psychosis among persons with severe mental illness. In addition, police officers may encounter scenes that are the aftermath of considerable violence, especially when weapons are involved. Although suicidal behavior is an important and growing social problem that directly affects patrol officers, little scientific attention has been given to the examination of calls to police for assistance in suicidal behavior. The objective of this study was to examine the epidemiology of calls for police assistance in relation to suicide and suicide attempts in an urban environment and to identify implications for police training and preparedness.

Methods

Data provided by the Toronto Police Service allowed us to conduct a five-year retrospective examination of suicide and suicide attempts in an urban setting. These data include information about demand for police response to calls for service pertaining to suicidal behavior, by victim's age and sex, as well as the time and location of the incident. The unit of analysis for this study was the service call rather than the individual.

Toronto, with a population of 2.5 million, has the largest urban police force in Canada, making it an ideal setting in which to explore patterns of calls for suicidal behavior. The city covers an area of 243.5 square miles and is divided into 16 police divisions ranging from 4.4 to 49.1 square miles, each with its own police station and with defined geographic boundaries of operation. In 2001 the uniformed force was 5,028, with approximately 194 uniformed officers per 100,000 population.

The definition of suicidal behavior includes both completed suicides and suicide attempts. Suicide attempt is defined as self-injurious behavior, with or without an intention to die, that does not result in death. We classified suicide methods as either physical or chemical. Physical methods include using a knife; hanging or strangulation; jumping from a building, bridge, or moving vehicle; using a firearm; using a plastic bag; drowning; burning; electrocution; using gas; and battering. Chemical methods include ingestion of a toxic or potentially toxic substance, including sleeping pills, barbiturates, narcotics, aspirin, poison, carbon monoxide, and alcohol. The study was approved by the research ethics board of St. Michael's Hospital.

Results

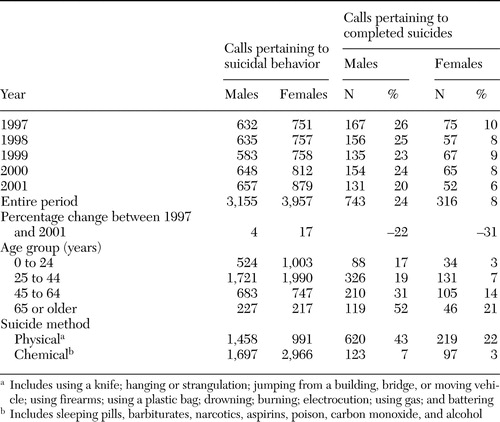

During the five-year period, there were an average of 1,422 annual calls for suicidal behavior, 631 involving men and 791 involving women (Table 1). Completed suicides accounted for 15 percent of calls (24 percent of male callers and 8 percent of female callers). Over time, calls for assistance for incidents of suicidal behavior increased by 11 percent overall (an increase of 4 percent in the number of calls involving men and of 17 percent in the number of calls involving women). The number of calls pertaining to completed suicides decreased by 24 percent over the study period (22 percent for male callers and 31 percent for female callers). When population growth was taken into account (a 10 percent growth for both males and females), the overall change in the number of calls per person in the population was 7 percent more calls for females and 6 percent fewer calls for males; decreases in the number of completed suicides were even greater after adjustment for population growth (a 32 percent decrease for males and a 41 percent decrease for females).

A majority of calls were related to females engaging in suicidal behavior (56 percent of calls). Of all calls pertaining to older males, 52 percent were for a completed suicide, indicating that men aged 65 years or older who engaged in suicidal behavior were disproportionately at risk of death. The ratio of suicide attempts to completed suicides in the overall sample was 6:1, with a much higher ratio for females (12:1) than males (3:1).

Analysis of change over time from the baseline year of 1997 (data not shown) indicated an increase in the number of calls for suicidal behavior among males aged 16 to 20 years (37 percent) as well as a substantial increase in the number of calls involving women in mid- and later life (an increase of 70 to 90 percent), although relatively small numbers were involved.

As can be seen from Table 1, men are almost equally as likely to use chemical means as physical means, whereas women are more likely to use chemical means. Men are more likely to die from use of physical methods than women (43 percent of male suicides compared with 22 percent of female suicides). We examined the changing distribution of suicidal behavior by physical and chemical methods for the four years after the 1997 baseline (data not shown). The results suggest that both men and women are increasingly using chemicals in both attempted and completed suicides.

In a separate analysis (data not shown), we found that calls were unevenly distributed across police divisions, with a greater concentration in the downtown core. We also found divisional differences in police response to calls, with a lower ratio of dispatched calls per police officer in the downtown core relative to the outlying areas. These divisional differences can be partially explained by the density of police officers by division. The downtown core encompasses Toronto's principal business and entertainment district, which has a low residential population and therefore a greater officer-to-resident population ratio in these divisions.

Over the five-year study period, each division employed an average of 188 police officers, who responded to 241,253 dispatched calls per year. These numbers translate to 259 calls per officer in each division per year. The low number of calls per officer does not reflect the number of response units available for calls on a daily basis, because of factors such as shift schedule, time detractors, the proportion of officers for the primary response function, and a two-person-per-car requirement (based on a collective agreement). Thus the actual number of officers assigned to a division is only 17 percent of available response units for calls on a daily basis. On the basis of these assumptions, the daily number of calls per officer per unit was about 4, not 1. The mean number of calls for suicidal behavior was 1.9 per 1,000 dispatched calls.

Discussion

Suicide is a major social problem that has been made more visible by deinstitutionalization. Police services have historically responded to crises in the community. However, the provision of mental health assistance by police officers has increased over time. Using a unique data set provided by the Toronto Police Service, we established call service patterns for suicidal behavior in an urban setting. Our findings suggest an increase in the number of calls for suicidal behavior requiring police response over the five-year study period, with greater increases for females than males. Although the total number of calls for suicidal behavior increased, the number of calls for assistance for completed suicides decreased over time. A finding of great concern is the number of calls for completed suicides among older men relative to other age-sex groups. Men appear to be using physical means—and to lethal effect—more often than women. An additional finding of concern is the substantial increase in the number of calls for suicidal behavior involving women in midlife, which suggests a change in the number of women engaging in suicidal behavior or in repetitious acts of self-harm.

Although the demand for police response to suicidal behavior did not account for a high percentage of total calls to police, it is particularly serious and is treated as such by the police. In Toronto, all mental health calls require a response from a team of two police officers. Depending on the severity of the situation, up to six officers may be dispatched to the scene. Although a majority of calls for suicidal behavior were concentrated within police divisions in the central core of the city, the proportion of calls for suicidal behavior varied by downtown division, which suggests that demand on police resources is not dictated by an "inner city" phenomenon.

Our study data capture attempted and completed suicides reported through calls for police assistance. Information about completed suicides and suicide attempts, such as coroners' reports and use of emergency services that did not originate from a police call, are not included. Discovery of suicidal behavior by police during routine patrols would not be included in calls for service data, but in all likelihood this type of incident represents a very small proportion of all incidents.

These data may not be wholly representative of suicidal behavior in urban settings. Overall ratios of the number of attempted suicides to completed suicides reported in the literature range from 10:1 to 100:1, whereas we found a lower ratio of 6:1. This discrepancy may reflect the lack of reliable data on suicide attempts, differences in the proportion of completed suicides between rural and urban areas, and the types of suicidal behavior that result in calls to police.

Service data have several limitations. Undercounting may occur as a result of reluctance of individuals to report problems to police. In addition, inaccurate descriptions of the situation by the caller may lead to misclassification of calls. Although these concerns may be warranted for criminal activity, calls for service for suicidal behavior may represent a special case in which people are more willing to reach out to police when they encounter a person in distress, especially someone who is exhibiting suicidal behavior. Suicidal intent is often obvious to the witness, and attending officers are required to complete a report that indicates whether the incident was fatal or nonfatal.

The actual number of calls for assistance for suicide attempts increased during the study period, with a concomitant decrease in the rate of completed suicides. The increase in the rate of self-injurious behaviors that did not result in death may reflect repeat suicide attempts. Unfortunately, the aggregate data available to us do not distinguish repeat attempts. Repeat suicidal behavior is more common among persons with severe mental disorders, especially persons with borderline personality disorder. Cutting is one of the primary methods used in this population (7). Although it is violent, cutting is not necessarily lethal, but it can lead to frequent visits to the emergency department or calls to the police. The proportion of occurrences in this population that result in calls to the police is not known.

Police encounters with people who have mental illness do not fit the official perception of a police officer's line of work and also result in lengthy downtime from regular duties (8). Police officers are required to handle cases within a reasonable amount of time and with finite resources, but their interactions with suicidal individuals may be extensive (5). In situations in which violence is not apparent and there is no clear role for law enforcement, it seems counterproductive and potentially inappropriate to use police resources. In these situations, health care professionals may play a more vital role.

Recognizing the expanding role of the police in crisis intervention and the need to balance effective intervention with police time constraints, it is important to foster cooperation between the police, the mental health system, and the health service system to adequately deal with mental health crises in the community. Initiatives in North America and Australia are moving slowly in that direction, but only in the past decade have partnerships emerged between the police and mobile crisis units. Some police forces are actively training their officers in mental health issues to enable them to effectively and quickly diffuse mental health crises (9). Other forces use mobile crisis intervention teams composed of a crisis nurse and a police officer, who together respond to 911 calls pertaining to emotionally disturbed persons, as is the case in a two-year collaborative project in Toronto (10). Further research should explore the use of multicomponent crisis intervention programs to train fire, ambulance, emergency, and police workers in crisis management from the precrisis to acute crisis to postcrisis stages.

Conclusions

Patterns of suicide changed over a five-year period in this study, with police responding to more incidents involving young males as well as women in mid- to later life. The type of suicidal behavior may also be changing over time, such that police officers are increasingly likely to respond to situations involving chemical poisoning rather than physical suicide methods. Understanding the changing patterns of suicidal behavior is important for police training initiatives, which may have to be adapted to respond to changes in both the demographic characteristics and methods of suicide.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and the Toronto Police Service, with special thanks to Scott Maywood and Hans Peterson.

Dr. Matheson, Ms. Creatore, Mr. Gozdyra, Dr. Rourke, and Dr. Glazier are affiliated with the Centre for Research on Inner City Health at St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto, Canada. Dr. Matheson is also with the department of public health sciences of the University of Toronto. Dr. Moineddin is with the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, with which Dr. Glazier is also affiliated. Dr. Rourke is also with the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto. Send correspondence to Dr. Matheson at 30 Bond Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5B 1W8 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of calls for police assistance for suicidal behavior in Toronto

1. Hans-Joachim H, Rössler W: Deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients in Central Europe. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 249:115–122,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lester D, Leenaars A: Suicide in Canada and the United States: a societal comparison, in Suicide in Canada. Edited by Leenaars A, Wenckstern S, Sakinofsky I, et al. Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1998Google Scholar

3. Szanto K, Prigerson HG, Reynolds CF: Suicide in the elderly. Clinical Neuroscience Research 1:366–376,2001Crossref, Google Scholar

4. McCall PL, Land KC: Trends in white male adolescent, young-adult, and elderly suicide: are there common underlying structural factors? Social Science Research 23:57–81,1994Google Scholar

5. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, DeCuir WJJR: The police and mental health. Psychiatric Services 53:1266–1271,2002Link, Google Scholar

6. Borum R, Deane MW, Steadman HJ, et al: Police perspectives on responding to mentally ill people in crisis: perceptions of program effectiveness. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 16:393–405,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Soderberg S: Personality disorders in parasuicide. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 55:163–167,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bittner E: Police discretion in emergency apprehension of mentally ill persons. Social problems 14:278–292,1967Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Deane MW, Steadman HJ, Borum R, et al: Emerging partnerships between mental health and law enforcement. Psychiatric Services 50:99–101,1999Link, Google Scholar

10. Read NE, Rourke SB, Wasylenki D. Mobile crisis intervention in the inner city (abstract). Journal of Urban Health 9:S87, 2002Google Scholar