A Comparison of Service Use and Costs Among Adults With ADHD and Adults With Other Chronic Diseases

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study compared health service use and costs among adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and adults with depression, diabetes, or seasonal allergic rhinitis (seasonal allergy). METHODS: Pharmacy and medical claims data from January 1, 1999, to December 31, 2001, were obtained from a large U.S. managed care plan. Patients were divided into one of four mutually exclusive cohorts (ADHD, depression, diabetes, or seasonal allergy) on the basis of their diagnosis or prescriptions. Age, gender, comorbid conditions, and type of dominant provider were compared for the four groups. Thereafter, general linear models with post-hoc multiple comparison tests were used to compare health service use and costs by site of service. RESULTS: The study population included 143,561 patients. The four mutually exclusive groups included 58,017 with depression, 45,479 with diabetes, 33,272 with a seasonal allergy, and 6,793 had ADHD. Comorbid mental health conditions occurred with significantly greater frequency among patients with ADHD and among those with depression than among patients in the other groups. Patients with ADHD and those with depression received care from a mental health provider significantly more often than those with diabetes or a seasonal allergy. Patients with ADHD had fewer average outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department visits than patients with depression or diabetes, and office visit frequency for patients with ADHD was significantly different from that of patients with a seasonal allergy. Annual total costs were lowest among patients with a seasonal allergy ($2,743), which were not significantly different than the costs for patients with ADHD ($3,020). CONCLUSIONS: Adult ADHD poses an economic burden that is less than that of depression or diabetes but greater than that of a seasonal allergy.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has long been considered a disorder of childhood; recent studies suggest that 30 to 60 percent of children who have been given a diagnosis of ADHD continue to manifest symptoms into adulthood (1,2,3,4). The American Psychological Association describes ADHD as a persistent pattern of inattention that can occur with or without hyperactivity and impulsivity (5). Although there are not separate criteria for child and adult ADHD, the symptoms of ADHD may manifest differently. For example, inattention, distractibility, cognitive deficits, and impulsivity are common to both children and adults with ADHD; however, hyperactivity, which commonly occurs among children with ADHD, is not as frequent among adults with the disorder (6). Physician recognition of adult ADHD is further complicated because adults with this disorder often present with comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as anxiety, depression, or a substance use disorder (2,7,8,9,10).

ADHD among adults can result in significant negative effects from both personal and societal perspectives. Specifically, adults with ADHD are more likely to change jobs, be absent from work, have difficulty sustaining relationships, have low self-esteem, have lower academic performance, and complete fewer years of education (11,12,13). Evidence from several studies indicates that ADHD also poses a significant economic burden in terms of medical care use and costs. Data from Swenson and colleagues (13) indicate that medical and pharmacy costs for adults with ADHD are approximately two to three times as high as those costs for adults without ADHD. These results are generally consistent with data for children from a nationally representative survey (14), a population-based cohort (15), and a health maintenance organization population (16). In terms of how use and costs for ADHD compare with those for other types of chronic diseases, Chan and colleagues (14) found that children with ADHD used significantly more outpatient services and had more prescriptions filled per year than children with asthma. Furthermore, children with ADHD incurred significantly higher health care costs than children with asthma and children in the general population.

Although there is increasing awareness of the significant negative psychosocial outcomes associated with adult ADHD, there is currently a lack of literature about the economic health care burden associated with this disorder. Because data by Swensen and colleagues (13) indicate that adults with ADHD incur more health service costs than adults without ADHD, a logical next step is to place service use and costs of adult ADHD within an appropriate context. Therefore, this study compared health care use and costs among adults with ADHD with those among adults with other chronic diseases. The primary objectives of this study were to compare and contrast patient characteristics, health service use patterns, and costs among adults with ADHD with those of adults with three chronic diseases: depression, seasonal allergic rhinitis (seasonal allergy), and diabetes.

Methods

Data source

This study was conducted by using medical claims, pharmacy claims, and enrollment data from a large U.S. national managed care plan. Plan sites were geographically diverse and followed a discounted, fee-for-service, independent practice association model. During the patient identification period, plan sites covered more than 5.8 million commercially insured enrollees and more than 248,000 Medicaid enrollees. Eligible covered services included inpatient services, ambulatory services, and prescription drug benefits.

Participants

Patients were identified between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2000. A 12-month baseline period and a 12-month follow-up period were required to identify and compare demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, health service use, and costs among adults with ADHD, depression, diabetes, or a seasonal allergy. The three comparison groups were selected a priori because these chronic diseases tend to occur across the adult lifespan, are treated primarily within outpatient settings, and represent various types of conditions (medical and mental) suitable for comparison with ADHD. Depression was selected because it is a prevalent and recurrent mental health condition, with a lifetime U.S. prevalence estimation of 16.2 percent, and because it is associated with multiple episodes (17,18). Diabetes was chosen because it is a prevalent chronic medical condition that affects approximately 18.2 million people in the United States (19). Finally, seasonal allergy was selected because it is typically a less severe chronic medical condition on the spectrum of possible comparison diseases. To enable accurate comparisons between the four groups, patients could appear in only one group. However, patients were allowed to have all other diagnoses related to mental health besides depression.

To address the loss of generalizability caused by the exclusivity of the groups, output from a log-adjusted linear regression model is presented. The model shows the effect of multiple comorbid conditions on costs.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study patients were as follows. For the ADHD cohort, a diagnosis of ADHD (ICD-9 code 314.0x) or at least two stimulant prescriptions and no diagnosis of narcolepsy (ICD-9 code 347.xx) in 2000 were required. For the depression cohort, a diagnosis of depression (ICD-9 codes 296.2x-296.3x, 296.9x, 298.0x, 300.4x, 301.12, 308.0x, 309.0x-309.1x, 309.4x, 311.xx, and 313.1x) in 2000 was required. For the diabetes cohort, a diagnosis of diabetes (ICD-9 code 250.xx) in 2000 was required. For the seasonal allergy cohort, a diagnosis of seasonal allergic rhinitis (ICD-9 code 477.xx) and no use of nonsedating antihistamines during winter months in 2000 were required. All study patients had to be continuously enrolled in the managed care plan during the study period, had to be aged at least 18 years, and had to have no diagnosis for the other three conditions in 2000.

The service date on the first qualifying claim was considered to be the index date and was unique to each patient. The 12-month baseline and follow-up periods were anchored around the index date.

Comorbid conditions

Presence of comorbid conditions was based on medical claims data. If a patient had at least one diagnosis in any position (for example, primary or secondary) on a physician or facility claim during the 12-month baseline period, the patient was assumed to have that particular comorbid condition. The mental health-related comorbid conditions of interest included substance use disorders, affective disorders, anxiety disorders, depression, and adjustment disorders. These comorbid conditions were selected because they have been reported in the literature as commonly occurring with ADHD or because they were present with some frequency (at least 5 percent of cases) within the medical claims data. Other mental health disorders, which occurred relatively infrequently (in less than 5 percent of cases) in the medical claims data, were captured as "other mental health disorder." Comorbid medical conditions were identified by codes in the 2002 ICD-9 codebook and were grouped into disease categories—for example, musculoskeletal system disease, respiratory disease, and circulatory disease).

Health service use patterns and cost

To determine what type of health care professional was providing a majority of care to patients in the specified disease groups, a dominant provider specialty variable was created. The dominant provider specialty was determined on the basis of the frequency of patient visits to a given provider type during the entire study period; the most frequently seen provider was the dominant provider. Dominant provider categories included generalist (family practitioner, internal medicine practitioner, and obstetrician or gynecologist), mental health (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker or mental health counselor, behavioral health clinic, outpatient mental health facility, or substance abuse facility), or other specialist (for example, endocrinologist, allergist, or gastroenterologist). In cases in which two provider types had an equal number of visits, mental health providers were counted first, followed by other specialists and then by generalists.

Type of health services used in the 12-month follow-up period included outpatient care (office visit and outpatient hospital visit), emergency department care, inpatient care (inpatient hospitalization), and prescriptions filled. Costs were recorded by site of service and were based on health service use. The costs were calculated from the health care perspective and included associated health plan costs and patient copayments. Because of the use of data from a single independent practice association, cost differences observed between disease states reflect differences in volume and mix of services and, therefore, not price schedule differences.

Statistical analyses

The prevalence of ADHD was calculated among all adults in the managed care plan, irrespective of whether these patients had comorbid depression, diabetes, or seasonal allergy or were continuously enrolled. Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine baseline patient characteristics, including age, gender, comorbid medical and mental health conditions, and provider specialty type. Bivariate comparisons were computed by using chi square tests of differences in proportions and t tests of differences in means. A log-adjusted linear regression analysis was conducted for all adult patients with ADHD to determine the effect of comorbid conditions on costs. Kennedy's retransformation correction (exp[β-1/2σ2]) of the parameter estimate was used (20).

General linear models with Tukey's honest significant different post-hoc multiple comparison tests were used to compare use and cost measures across the four cohorts. The models included several covariates to adjust for potential confounding variables, including age, gender, plan location, physician specialty, and comorbid conditions (specific covariates are listed in each table). All analyses were completed in SAS version 8.2.

Results

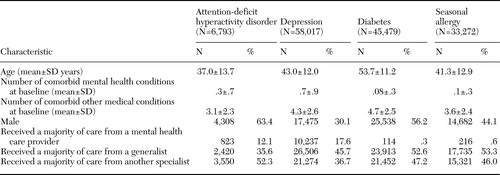

For the entire managed care population, the prevalence of adult ADHD was .67 percent (28,957 of 4,349,827 enrollees) and was higher for males than for females (16,447 males, or .77 percent, compared with 12,510 females, or .56 percent; p<.05). Data for 143,561 patients were included in the analysis: 6,793 patients with ADHD, 58,017 patients with depression, 45,479 patients with diabetes, and 33,272 patients with a seasonal allergy. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1 for the four mutually exclusive groups. The ADHD cohort had a higher percentage of males (chi square analysis, p<.05) and a significantly younger average age (t test, p<.05) compared with all other cohorts.

Comorbid conditions

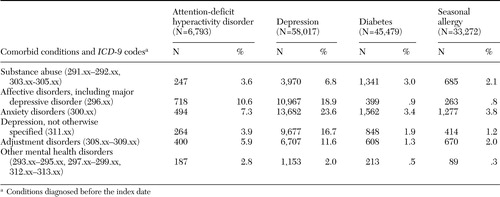

As depicted in Table 2, comorbid mental health conditions occurred with greater frequency among adults with ADHD and adults with depression compared with adults in the other groups. Specifically, the depression group had the highest percentage of patients with substance use disorders (6.8 percent), affective disorders (18.9 percent), anxiety disorders (23.6 percent), and adjustment disorder (11.6 percent) (chi square analysis, p<.05). The ADHD group had the highest percentage of patients with other mental health disorders (2.8 percent) (chi square analysis, p<.05) and had significantly higher rates of affective disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and adjustment disorder compared with the diabetes group and the seasonal allergy group (chi square analysis, p<.05).

Regarding medical conditions, patients with ADHD had significantly fewer comorbid conditions (3.1 conditions) than adults with depression (4.3 conditions), diabetes (4.7 conditions), or allergies (3.6 conditions). The most common comorbid conditions included respiratory disease for adults with ADHD and adults with depression (4,980 of 10,779 patients with ADHD, or 46 percent, compared with 29,369 patients with depression, or 51 percent), circulatory disease for adults with diabetes (26,364 patients, or 58 percent), and musculoskeletal system disease for adults with a seasonal allergy (11,783 patients, or 35 percent).

Health service use patterns and cost

As shown in Table 1, patients with ADHD had generalists as their dominant providers less frequently than patients in the other groups (p<.001). In comparison, patients in the ADHD and depression cohorts were more likely than patients in the other disease groups to have mental health providers as their dominant provider (p<.001).

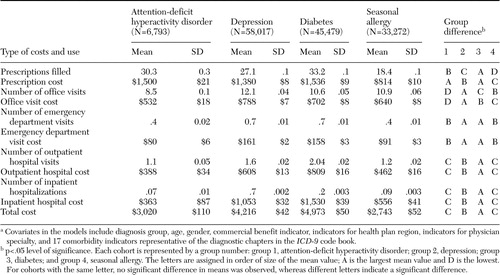

Average adjusted use and costs for the 12-month follow-up period is shown for each cohort in Table 3. Compared with patients in the other cohorts, patients in the ADHD group had the lowest average number of office visits and lowest average costs for office visits. Patients with ADHD had fewer average outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department visits than patients with diabetes and depression (t test, p<.05), but mean visit frequency was not significantly different from that of patients with a seasonal allergy. This pattern was also consistent for costs. Total costs during the follow-up year were highest for patients with diabetes ($4,973) and lowest for patients with a seasonal allergy ($2,743). Although total costs for patients with ADHD were significantly lower than those for patients with diabetes and patients with depression, total costs were not significantly different from those for patients with allergies. Patients with diabetes filled significantly more prescriptions than the other groups. Patients with diabetes had the highest average prescription costs ($1,536), but these costs were not significantly different from those for patients with ADHD ($1,500).

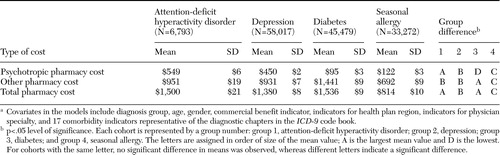

To understand drivers of total prescription costs in each group, costs were divided into psychotropic drug costs and all other therapeutic classes, as shown in Table 4. For patients in the ADHD group, nearly 37 percent of their pharmacy costs were spent on psychotropic drugs, which were significantly higher than that for patients in the other disease groups, including the depression group. All pairwise comparisons of psychotropic pharmacy costs were significantly different (p<.001). The highest percentage of total pharmacy costs for the diabetes and seasonal allergy groups was spent on other therapeutic classes (94 percent and 85 percent, respectively). Pairwise comparisons of other pharmacy costs were significantly different (p<.001), with the exception of the comparison between the ADHD and depression groups.

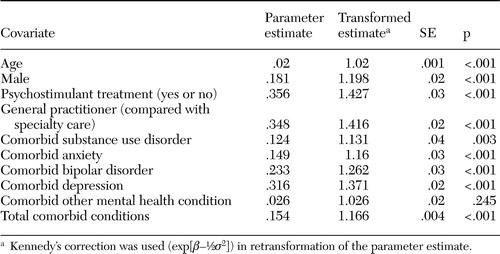

To show the influence that multiple comorbid conditions may have on total costs among patients with ADHD, parameter estimates from a log-adjusted linear regression model are shown in Table 5. This model included continuously enrolled patients with ADHD in the managed care plan, regardless of whether they also had a diagnosis for the other three conditions (N=10,779). The results indicate that among adults with ADHD, the addition of comorbid depression resulted in 37 percent higher total costs per year when all other covariates in the model were controlled for. Similarly, each additional comorbid condition results in 17 percent higher total costs.

Discussion

The prevalence of diagnosed adult ADHD in this large managed care population was .67 percent. This prevalence estimate was considerably lower than prevalence estimates (including diagnosed and undiagnosed adults) that have been reported in the literature, which range from 1 to 7 percent, assuming a 4 to 12 percent prevalence of childhood ADHD and a 30 to 60 percent retention of symptoms into adulthood (1,2,3,421,22). The lower prevalence rate that we detected may be at least partially due to the difficulty of distinguishing ADHD from other comorbid conditions related to mental health, such as depression, (2,23) as well as the assumption that ADHD is purely a childhood disorder. A lack of education about adult ADHD, including its symptom presentation and associated impairments may also be related to the low diagnosis rate within this managed care population. Finally, this study did not include patients who did not have health insurance. Adults with ADHD who are having difficulty holding down a job or who are in the correctional system would not be included in the prevalence estimate and may have higher rates of ADHD.

Patients in the ADHD and depression groups were more likely than those in the other groups to receive care from a mental health provider, and patients with ADHD were more likely to see specialty providers as well. Although this finding may be due to the particular health plan structure in which patients do not have to see a primary care provider before seeing a specialist, this pattern of care would likely be the same across disease groups. One possibility is that patients with mental health conditions may have a more complicated presentation and, therefore, are more frequently referred to specialty care. For example, the somatic complaints that often co-occur with depression (24,25) may lead primary care providers to refer these patients to specialty care for evaluation. In fact, a primary care study found that 80 percent of patients with internalizing conditions (that is, depression or anxiety) presented exclusively with somatic symptoms (24).

Adults with ADHD had lower rates of inpatient and outpatient use and lower costs than adults with depression and diabetes, but their rates and costs were similar to those for adults with a seasonal allergy. One explanation is that ADHD and seasonal allergy are not progressive disease states, whereas diabetes often results in long-term disease-related complications (26,27,28). For depression, use and costs could be related to the increased rates of somatic symptoms (24,25) and suicidality (24) that are associated with this disorder. In contrast to their lower outpatient and inpatient use rates and costs, adults with ADHD had higher rates of prescription use and costs than adults with depression and diabetes. This difference in use and costs was largely driven by the use of psychotropics, which were used at a higher rate among patients with ADHD than among patients in the other groups. Although this pattern was expected because ADHD is a mental health disorder, it is somewhat surprising that it is associated with higher costs than depression. Because ADHD often co-occurs with other mental health conditions (2,7,8,9,10), providers may have difficulty sorting out which symptoms are related to ADHD and which symptoms are due to another mental health condition, making the choice of appropriate treatment challenging. Polypharmacy is one possible result of this predicament and could translate into increased psychotropic medication costs. This topic merits future exploration.

The results of this study should be considered within the limitations of the data source and study design. First, the sample included managed care enrollees, which may limit generalizability to other populations. In addition, benefit limitations—such as caps on services, out-of-pocket maximum costs, and lifetime benefits—may have an impact on the cost calculations. Furthermore, for some conditions substantial health care use may not be found in the claims data. For example, patients with depression may be more likely to pay for some services without submitting a claim to the health plan in order to avoid the health plan's having a record of their depression, which may lead to differential "missing" costs and use data across the cohorts.

Second, in order to allow for pairwise comparisons of costs between the four groups, patients with more than one condition of interest were excluded from the study. This exclusion likely had the largest effect on the ADHD cohort sample size, because ADHD and comorbid depression is not uncommon (24). Results indicated that among all 10,779 patients with ADHD in the managed care plan the presence of depression resulted in 37 percent higher total costs for patients with adult ADHD (Table 5). Future studies could consider a stepped approach that compares patients with ADHD alone with patients with ADHD plus other comorbid mental health conditions. A final limitation to consider is that claims data are collected for the purpose of payment and not research. Administrative claims data used for secondary research other than its intended purpose may be limited by lack of clinical data and concerns about data quality (29). Although claims data are sufficiently precise to estimate costs and use patterns as they occur outside the constraint of a clinical trial, they do not allow for assessment of whether filled prescriptions were taken and they do not reflect any medical care or medications received outside of the area of the managed care plan or through samples.

Conclusions

Adult ADHD poses an economic burden equal to or greater than that for a seasonal allergy but less than that for depression or diabetes. Because of the negative psychosocial outcomes associated with adult ADHD, it appears that the health care costs are warranted. The large number of these patients who were seen by specialists suggests that their course of care was complicated. Whether or not this is the case is an interesting research question that has significant implications for both managed care and health care policy. It is possible that providing education about diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD to primary care providers could enhance the ability of generalists to manage this mental health condition.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. The authors thank Ralph Swindle, Ph.D., for his review of the manuscript and Carolyn Harley, Ph.D., for her statistical assistance.

Ms. Hinnenthal is affiliated with the department of health economic and outcomes research at Ingenix in Eden Prairie, Minnesota. Dr. Perwien and Dr. Sterling are with the department of outcomes research at the U.S. Medical Division of Eli Lilly and Company in Indianapolis, Indiana. Send correspondence to Dr. Sterling at Eli Lilly and Co., Lilly Corporate Center, Indianapolis, Indiana 46285 (e-mail, [email protected]). Preliminary results of this study were presented as a poster at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Meeting, held October 17, 2003, in Montreal.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients in a large managed care plan, by mutually exclusive diagnosis group

|

Table 2. Comorbid mental health conditions of patients in a large managed care plan in the 12-month baseline period, by mutually exclusive diagnosis group

|

Table 3. Adjusted 12-month follow-up use and costs among patients in a large managed care plan, by mutually exclusive diagnosis groupa

a Covariates in the models include diagnosis group, age, gender, commercial benefit indicator, indicators for health plan region, indicators for physician specialty, and 17 comorbidity indicators representative of the diagnostic chapters in the ICD-9 code book.

|

Table 4. Adjusted 12-month prescription drug costs among patients in a large managed care plan, by mutually exclusive groupsa

a Covariates in the models include diagnosis group, age, gender, commercial benefit indicator, indicators for health plan region, indicators for physician specialty, and 17 comorbidity indicators representative of the diagnostic chapters in the ICD-9 code book.

|

Table 5. Adjusted 12-month total costs for continuously enrolled patients in the managed care plan with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (N=10,779)

1. Mannuzza S, Klein RG: Adolescent and adult outcomes in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, in Handbook of Disruptive Behavior Disorders. Edited by Quay HC, Hogan AE. New York, Klumer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999Google Scholar

2. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al: Adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controversial diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 7):59–68,1998Medline, Google Scholar

3. McCann BS, Roy-Byrne P: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and learning disabilities in adults. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry 5:191–197,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wender PH, Wolfe LE, Wasserstein J: Adults with ADHD: an overview. Annals of the New York Academy of the Sciences 931:1–16,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

6. Feifel D: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Postgraduate Medicine 100:207–211, 215–218,1996Medline, Google Scholar

7. Biederman J, Munir K, Knee D, et al: High rate of affective disorders in probands with attention deficit hyperactivity disorders and in their relatives: a controlled family study. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:330–333,1987Link, Google Scholar

8. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, et al: Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, cognition, and psychosocial functioning in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1792–1798,1993Link, Google Scholar

9. Murphy K, Barkley RA: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Comprehensive Psychiatry 37:393–401,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Borland BL, Heckman HK: Hyperactive boys and their brothers: a 25-year follow-up study. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:669–675,1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Weiss MA, Hechtman LT, Weiss G: ADHD in Adulthood: A Guide to Current Theory, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Baltimore, Md, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999Google Scholar

12. Barkley RA, Murphy KR: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Workbook, 2nd ed. New York, Guilford Publications Inc, 1998Google Scholar

13. Swensen A, Secnik K, Page MJ: Comorbidities and costs of adult patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacoeconomics 23:93–102,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Chan E, Zhan C, Homer CJ: Health care use and costs for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: national estimates from the medical expenditure panel survey. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 156:504–511,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Leibson CL, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, et al: Use and costs of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA 285:60–66,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Guevara J, Lozano P, Wickizer T, et al: Utilization and cost of health care services for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 108:71–78,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095–3105,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Solomon DA, Keller MD, Leon AC, et al: Multiple recurrence of major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:229–233,2003Link, Google Scholar

19. All About Diabetes. American Diabetes Association. Available at http://www.diabetes.org/about-diabetes.jsp. Accessed April 5, 2005Google Scholar

20. Kennedy P: Estimation with correctly interpreted dummy variables in semilogarithmic equations. American Economic Review 71:801,1981Google Scholar

21. Hill JC, Schoener EP: Age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1323–1325,1996Google Scholar

22. Hesslinger B, Tebartz Van Elst L, et al: A psychopathological study into the relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adult patients and recurrent brief depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 107:385–389,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Searight HR, Burke JM, Rottnek F: Adult ADHD: evaluation and treatment in family medicine. American Family Physician 62:2077–2086, 2091–2092,2000Medline, Google Scholar

24. Kirmayer LJ, Robbines JM, Dworkind M, et al: Somatization and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:734–741,1993Link, Google Scholar

25. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, et al: An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. New England Journal of Medicine 341:1329–1335,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Aiello LP, Gardner TW, King GL, et al: Diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 21:143–156,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Diabetic nephropathy: American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 26:S94-S98, 2003Google Scholar

28. Arauz-Pacheco C, Parrott MA, Raskin P: The treatment of hypertension in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 25:134–147,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Iezzoni LI: Assessing quality using administrative data. Annals of Internal Medicine 127:666–674,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar