Datapoints: Medicaid as a Payer for Services Provided by Psychiatrists

In 1999 Medicaid insured more than 21 million people with low incomes (1), and in 2001 Medicaid emerged as the single largest payer (26 percent) for mental health and substance abuse services in the United States (2). We were interested in the role of Medicaid in psychiatrist reimbursement, a question not previously studied. We analyzed weighted, national, self-report data from 2002 (N=1,189). Data were from the National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (NSPP) of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's Practice Research Network. The 2002 NSPP used as its sampling frame the American Medical Association's Masterfile, which includes all U.S. psychiatrists. Details of the methods used are available elsewhere (3).

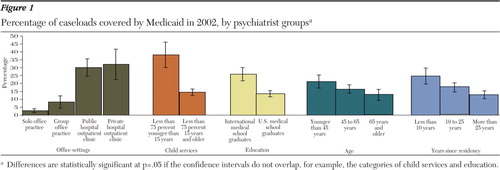

In 2002 the proportion of psychiatrists' caseload paid for by Medicaid was 17 percent, with no variation by gender. When the data were analyzed by psychiatrist and practice characteristics, the proportion of the caseload paid for by Medicaid ranged from 3 percent in solo office practice to 38 percent in practices in which more than 75 percent of the caseload was younger than 15 years (Figure 1).

The large role of Medicaid as a payer for services provided by some psychiatrists suggests that concerted attention should be paid to Medicaid policies that might restrict psychiatric coverage and reimbursement (4).

It will be particularly important to track changes for the psychiatrists who receive significant Medicaid reimbursement for their caseloads.

Dr. Jacobs and Dr. Steiner are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Yale University and the Connecticut Mental Health Center, 34 Park Street, New Haven, Connecticut 06519 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Wilk and Mr. Rae are affiliated with the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education of the American Psychiatric Association in Arlington, Virginia. Dr. Chen is with the department of health evaluation sciences of the University of Virginia Health Systems in Charlottesville, Virginia. Harold Alan Pincus, M.D., and Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., are editors of this column.

Figure 1. Percentage of caseloads covered by Medicaid in 2002, by psychiatrist groupsa

aDifferences are statistically significant at p=.05 if the confidence intervals do not overlap, for example, the categories of child services and education.

1. Maxfield M, Achman L, Cook A: National Estimates of Mental Health Insurance Benefits. DHHS pub no SMA-04–3872, Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004Google Scholar

2. Mark T, Coffey RM, McKusick DR, et al: National Expenditures for Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse Treatment, 1991–2001. SAMHSA pub no SMA-05–3999, Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005Google Scholar

3. Scully JA, Wilk JE: Selected characteristics and data of psychiatrists in the United States, 2001–2002. Academic Psychiatrist 27:247–251,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Frank RG, Goldman HH, Hogan M: Medicaid and mental health: be careful what you ask for. Health Affairs 22(1):101–113,2003Google Scholar